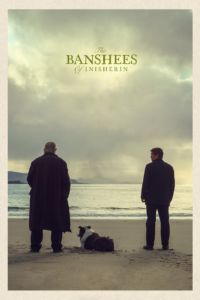

The Banshees of Inisherin

Posted By Nicholas R. Jeelvy On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledI have a rule about films: I don’t watch any made after 2008, which I consider to be the last year in which good films were made. Sometimes, however, my rule can be wrong and I’ll make an exception. I’m pleased to report that my rule was wrong about The Banshees of Inisherin, a 2022 Irish film starring Colin Farrell and Brendan Gleeson and directed by Martin McDonagh.

Colin Farrell portrays Pádraic Súilleabháin, a farmer living on the fictional island of Inisherin, off Ireland’s western coast, in the 1920s, during the waning months of the Irish Civil War. He lives with his sister Siobhán, a bookish old maid, and his animals, of which Jenny the tiny donkey gets the most attention and relevance to the plot. A simple man, kind-hearted and friendly to everyone, he reserves the most affection for his best friend, the fiddler Colm Doherty, played by Brendan Gleeson. The film opens by showcasing the island’s amazing beauty, cultivated over time to feature lush green meadows demarcated by iconic stone walls. Pádraic is introduced as he is walking down a sunny village lane, greeting everyone in the friendly manner typical of romanticized rural locales, and indeed, everyone is nice to him — except for the local Garda (policeman) Peadar, who ignores him.

Pádraic is going to Colm’s house to pick him up on the way to the pub so that they can have a pint or two and share a conversation. The scene is full of light and color, drawing the viewer into a fantasy of slow-moving village life in bucolic Western Ireland; we are in Tolkien’s shire, but it is real.

And then, disaster strikes. Colm informs Pádraic that he doesn’t like him anymore and will not be joining him at the pub. Pádraic does not understand why Colm wants to end their friendship, and keeps thinking he’s done something wrong or that by changing his behavior in some way, he could convince Colm to be his friend again.

Colm, however, wants to end his friendship with Pádraic because he finds him dull and life on the small island uninspiring. As a musician who can feel himself ageing, Colm wants to be remembered, and so he has decided to spend the rest of his life thinking, composing, and teaching music to students. He thus feels he has no more time for Pádraic and his company. For all his genuine kindness, Pádraic simply isn’t the good and intelligent company that Colm needs if he’s to make the most of the rest of his life. As Colm later says to Pádraic during a fierce argument, “Nobody is remembered 50 years on for being nice.” We learn during a scene set in a confessional that Colm is struggling with despair. This suggests that his abrupt decision to break his friendship with Pádraic is an attempt to regain control of the life he sees slipping away.

[2]

[2]You can buy Trevor Lynch’s Classics of Right-Wing Cinema here [3].

Pádraic is unperturbed by Colm’s rejection and resolves to rekindle their friendship, but Colm rebuffs him once again and threatens to cut off his own fingers — and what’s more, the fingers of his fiddle hand — unless Pádraic does not stop badgering him. Nobody, including Pádraic, takes the threat seriously until Colm actually does cut off one of his own fingers, throwing it at Pádraic’s front door. It then becomes clear that this is no ordinary feud between villagers.

The film is set against the backdrop of the Irish Civil War of the 1920s, which was a conflict between the Irish Free State, which was a dominion of the British Crown and seen by its supporters as a step towards true independence, and the Irish Republican Army, which rejected the treaty with the British and saw the Irish Free State as just another means of subjugating the Irish people. The conflict between Pádraic and Colm is clearly meant to be an allegory for the war, which was fought for reasons many people did not understand and inflicted a great deal of suffering on the Irish people. The anti-treaty IRA could not countenance the oath of loyalty to the British monarch that had been imposed on the new Irish parliament. Being something of an inflexible ideologue myself, I can sympathize with that position, even if I can also understand the position of the Free State forces, who understood that rejecting the treaty would just mean a prolonged war with the British Empire. As an outsider, I can’t say who was right and who was wrong; just as the slow-witted village boy Dominic in the film, all I can say is that I’m against wars.

What I can understand, however, is the sensation of feeling trapped in a life that by all means shouldn’t feel like a trap. Pádraic, Colm, Siobhán, and all the other villagers live the sort of lives that are envied by today’s online Right. They live in an ethnically cohesive village, they are in touch with a land that is uncorrupted by modern technology, and seemingly spared from the whirlwind of political strife that’s enveloped the Irish mainland. They go to church and the pub, and are surrounded by green meadows and neat stone walls. They enjoy traditional music and are nice to each other. And yet, Colm is unhappy and bedeviled by despair — and so is Siobhán.

The online Right will rush to romanticize [4]the agrarian idyll of a picturesque Gaelic village, but will forget that rural life always had its discontents — and very often these discontents were the best that humanity had to offer. Colm feels as if he’s wasting his time on the tiny islands, fearful of being forgotten. Siobhán is an old maid in that always precarious position held by a woman with high intelligence. Young Dominic, the son of the rude and corrupt policeman, is a victim of both physical and sexual abuse at the hands of his father, who nakedly uses his power and position to bully Pádraic. When Siobhán dreams of moving to Dublin, we can almost imagine gaggles of online Right-wingers wanting to warn her that city life is meaningless or inauthentic, the implication being that she should be content with quietly wasting away as a spinster on the island while living her deeply authentic life in 1920s rural Ireland. And, of course, what could be more authentically human than a deep and all-consuming existential crisis as age, that thief of youth, encroaches? Colm’s drastic behavior is seen as an unnatural aberration by both Pádraic and the villagers, but every man born with talent has to fight a similar battle: either to live a normal life and fade into obscurity, or endure great suffering and loneliness while having a shot at immortality.

What the film does not explicitly state, but does a good job of implying, is that village life — and perhaps social life in general — relies on a degree of insincerity. Throughout the entire film, the only moment when Colm seems to reconsider his decision to end his friendship with Pádraic is when Pádraic gets drunk on whisky and launches into a tirade pointing out all of Colm’s flaws and the hypocrisy of his situation. This is further underscored by the presence of a large number of masks in Colm’s house. Colm finds the act of wearing a false face exhausting, and I can certainly empathize. But there is also a degree of wisdom in Pádraic drunken rant in which he defends “niceness.” The sophomoric retort would be to point out the irony of a man defending white lies and false faces under the influence of truth-revealing alcohol, but that does not mean there is not a case to be made for sparing our neighbors the terror of our true selves. Personally, as someone who’s worn many false faces, both in a professional and personal context, I can understand the fatigue they cause — but I can also see the necessity for such faces, even as I find them distasteful and uncomfortable.

A banshee is a spirit whose screaming portends a death. It is unclear in the film whether there is an actual banshee around, or if the purported banshee is merely old Mrs. McCormick, who delights in making the villagers squirm. Regardless, even though there is an actual death in the film as well, there are also many metaphorical deaths. Both Pádraic and Colm are metaphorically dead by the end of the film, having lost what made them the men they were. Pádraic, having allowed himself to become cruel and vengeful, has lost his kindness, and Colm, having cut off all the fingers of his left hand, has lost his music. The film is darkly comedic at times, but at its heart it is a deep and enduring human tragedy — the tragedy of disparate levels of satisfaction in which what works for some will not work for others. This disparity will inevitably lead to brutal, dehumanizing, and seemingly senseless conflict.

In both the small theater of village feuds or the large theater of ideological conflict, when a man strikes another man in anger, he sometimes hurts himself more than his purported foe.

* * *

Like all journals of dissident ideas, Counter-Currents depends on the support of readers like you. Help us compete with the censors of the Left and the violent accelerationists of the Right with a donation today. (The easiest way to help is with an e-check donation. All you need is your checkbook.)

For other ways to donate, click here [5].