The Abolitionists as Virtue-Signalers: Nehemiah Adams & A South-side View of Slavery

Posted By Spencer J. Quinn On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled2,933 words

One of the most neurotic things about white people is the desperation so many of them have to be perceived as moral. Most will virtue-signal in a variety of cheap and easy ways. Those who take it seriously will often descend into activism. But there is one way to virtue signal — indeed, it is the best way — that will sanctify one’s morality for all to see: care more for outgroup members than for ingroup members.

After all, what motivation could there be — other than pure angelic virtue — for doing something so utterly self-defeating?

I believe that the stark evolutionary divide between those whites who outgroup-signal versus those who acknowledge natural outgroup differences was one of the American Civil War’s main causes. It was never really about slavery per se. If it had been, there would have been abolitionist movements in the eighteenth century over indentured servitude, or in Ancient Rome for that matter. It’s hardly a coincidence that only when large numbers of blacks were enslaved did many whites finally get serious about abolishing that ancient and peculiar institution.

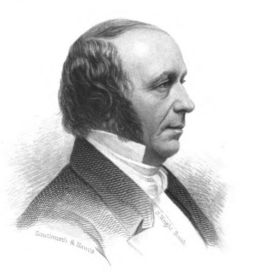

It was these nineteenth-century virtue-signaling whites, the abolitionists, whom Protestant clergyman Nehemiah Adams [2] addressed in his forgotten yet enlightening 1854 book, A South-side View of Slavery [3].

Adams had been a prominent abolitionist in his native Boston when he spent three months in the American South to restore his health. After seeing slavery up close and personal for the first time, however, he decided to revise his previous opinions and tell everyone in the North about it upon his return. His message was clear: North and South were on a collision course of either “fratricide or suicide,” and the main culprits were not Southern slaveowners, but wrongheaded Northern abolitionists who were forcing Southerners to cling fast to increasingly strict forms of slavery out of self-preservation.

Upon his arrival in Dixie, as a person fully indoctrinated in anti-slavery dogma, Adams was prepared for the worst:

I will merely add, that there was one thing which I felt sure that I should see on landing, viz., the whole black population cowed down. This best expresses in a word my expectation. “I am a slave,” will be indented on the faces, limbs, and actions of the bondmen. Hopeless woe, entreating yet despairing, will frequently greet me. How could it be otherwise, if slavery be such as our books, and sermons, and lectures, and newspaper articles represent?

But what did he see? He saw what he was not supposed to see — what we are still not supposed to see 170 years later: a thriving black slave population. He describes black slaves as cheerful, healthy, well-dressed, respectful, and competent. Adams writes, “A better-looking, happier, more courteous set of people I had never seen, than those colored men, women, and children whom I met the first few days of my stay in Savannah.” In another passage he describes a brigade of Savannah Negro firefighters, and asks why, if slavery had been the evil the abolitionists claimed, would the Savannah whites trust the people they oppress with protecting them from fires?

[4]

[4]You can buy Spencer J. Quinn’s young adult novel The No College Club here [5].

He likewise reports several times on the wonderful music and oratory in the black church services he attended. He also notes, time and time again, the cooperation and mutual respect that existed between blacks and whites in the South at that time. For example, many of the legal restrictions slaves had to abide by, and which Northerners found so horrifying, were in fact rarely enforced and often existed for good reasons.

Instead of warping a recalcitrant reality to fit his rigid ideology, Nehemiah Adams therefore did what any honest and clear-thinking person would do: He revised his ideology. This gave him newfound “feelings of affection for the blacks and respect for their masters.” It also led him to point a long finger at abolitionists for exacerbating the North-South divide. He argues that of course Southern whites would write laws to prevent blacks from assembling for public lectures or staying out after curfew. What else could they have done after abolitionist troublemakers started heading South to preach insurrection, escape, crime, and miscegenation? This posed a serious problem. Despite this, whites often allowed blacks to break such laws as long as trust had been established beforehand, which happened often, according to Adams.

And yes, one abolitionist was found with prints depicting “a white woman in no equivocal relations to a colored man.” Such a thing must have been outrageous on many levels to the Southern mind. According to Adams, the South was on the verge of abolishing — or at least phasing out — slavery itself in the early nineteenth century, when these sorts of intrusions started happening:

As northern zeal has promulgated bolder sentiments with regard to the right and duty of slaves to steal, burn, and kill, in effecting their liberty, the south has intrenched itself by more vigorous laws and customs.

Here is a list of observations and anecdotes which led Adams to believe that slavery as it was practiced in the antebellum South was unjustly maligned:

- Southern towns and cities were quite orderly. With a “wholesome restraint” placed upon the black population by Christianity and by the whites themselves, the widespread crime, homelessness, and poverty found in many Northern cities found no equivalent south of the Mason-Dixon line.

- Plantation work for slaves was “severe,” but no worse than it was for whites on Northern farms. Slaves were often given long breaks in the middle of the day, early dismissal at night, and Sundays and holidays off. So the slaveowners tended to be reasonable with their slaves.

- Slaves in some cases amassed wealth:

Some slaves are owners of bank and railroad shares. A slave woman, having had three hundred dollars stolen from her by a white man, her master was questioned in court as to the probability of her having had so much money. He said that he not unfrequently had borrowed fifty and a hundred dollars of her, and added, that she was always very strict as to his promised time of payment.

- Blacks’ human rights were protected by law and by public sentiment:

In Georgia it is much safer to kill a white man than a negro; and if either is done in South Carolina, the law is exceedingly apt to be put in force. In Georgia, I have witnessed a strong purpose among lawyers to prevent the murderer of a negro from escaping justice.

- In some cases, slaveowners defended their slaves’ honor with violence. For example, a slaveowner once challenged a town mayor to a duel for whipping his slave. In another instance, a slaveowner admonished a mechanic for abusing his slave and suffered a knife attack for his efforts.

- Many of the runaway slaves so celebrated in the North were either frauds looking to obtain cash and support from gullible whites, or ultimately returned to their masters after finding freedom not to their liking.

- Slaveowners were responsible for their slaves’ welfare from birth to death. If a slave became incapacitated due to age, illness, or injury, for example, his owner was required by law to support him for the rest of his natural life. As a result, pauperism among blacks in the antebellum South was almost unheard of:

I saw a white-headed negro at the door of his cabin on a gentleman’s estate, who had done no work for ten years. He enjoys all the privileges of the plantation, garden, and orchard; is clothed and fed as carefully as though he were useful. On asking him his age, he said he thought he “must be nigh a hundred;” that he was a servant to a gentleman in the army “when Washington fit Cornwallis and took him at Little York.”

- Many slaves themselves preferred the institution’s arrangement. One woman who provided washing services outside of her responsibilities to her master had saved up enough to buy her freedom. But she did not:

She says that if she were to buy her freedom, she would have no one to take care of her for the rest of her life. Now her master is responsible for her support. She has no care about her future. Old age, sickness, poverty, do not trouble her. “I can indulge myself and children,” she says, “in things which otherwise I could not get. If we want new things faster than mistress gets them for us, I can spare money to get them. If I buy my freedom, I cut myself off from the interests of the white folks in me. Now they feel that I belong to them, and people will look to see if they treat me well.” Her only trouble is, that her master may die before her; then she will “have to be free.”

- The slaves’ widespread religiosity had a felicitous impact on them, raising them up as a people and making them happy, moral, and industrious:

It is deeply affecting to hear the slaves give thanks in their prayers that they have not been left like the heathen who know not God, but are raised, as it were, to heaven in their Christian privileges.

Adams also includes a heartrending story of how an irresponsible and indebted slaveowner had sold a female slave but managed to retrieve her newborn in order to sell it as well. This appalled so many people in the region that the woman’s new owner and a lady philanthropist unbeknownst to each other had bid at this infant’s auction in order to restore him to his mother (which thankfully did end up happening). Adams points out that this auction was in violation of the law when it came to selling slaves under five years of age, and that several white Southerners had apologized to him for the revolting display. He also regretted the fact the Northern press would report only this story’s negative aspects and suppress the fact that it was white benevolence that corrected slavery’s flaws.

Adams rests his greatest hope on this last point. At the book’s conclusion, he still professes opposition to slavery; his greatest change is his newfound faith in the white Christians of the South to lead the way, gradually, toward abolition. “The south is best qualified to lead the whole country in plans and efforts for the African race,” he writes. “We will follow her.”

What should be deplored is not slavery as it was practiced in the South, but its all-too-common abuses, which were — in part — made worse by unwelcome abolitionist meddling. They also involved evil slaves as often as evil slaveowners. Adams reserves pointed scorn for unscrupulous slave traders who thought nothing of breaking up families to make a profit. Further, for all his superlative rhetoric on the virtues of black people and his undying love and solicitude for them — which has not aged well in post-1965 America — Adams retains a subtle, yet unyielding sense of race realism:

The two distinct races could not live together except by the entire subordination of one to the other. Protection is now extended to the blacks; their interests are the interests of the owners. But ceasing to be a protected class, they would fall prey to avarice, suffer oppression and grievous wrongs, encounter the rivalry of white immigrants, which is an element in the question of emancipation here, and nowhere else. Antipathy to their color would not diminish, and being the feebler race, they would be subjected to great miseries.

As a benevolent white supremacist brimming with Christian compassion, Adams proposes that the eventual and hoped-for emancipation of blacks be followed by a system in which blacks live in “some form of subordination to the whites.” He seems to have too much affection for them to send them back to Africa.

As once can see, Adams relies a lot on anecdotal evidence in A South-side View of Slavery. He offers few names, dates, or otherwise verifiable information. He instead simply describes what he saw, derives inferences from it, and hopes his book will be enough to dissuade Northerners from radical abolitionism. If his book were filled with fabrications and exaggerations, I imagine it would have been reported on at the time — but that does not seem to be the case, despite the shellacking Adams took in the abolitionist press after his book’s publication. For example, in 1857 the abolitionist paper The Liberator [6] deplored South-side as “as vile a work as was ever written, in apology and defense of ‘the sum of all villainies’ . . .” Not exactly an accusation of mendacity, is it?

Nevertheless, some of his depictions were so rosy, I began to suspect some kind of Potemkin plantation at work. Surely the lives of black slaves couldn’t have been quite this good. Also, the fact that Adams had amassed all this information after a mere three months in the South is rather suspicious. Could it have been that some white Southerners had gone out of their way to convince him of their point of view? This is essentially what Harriet Jacobs, a former slave, accuses Adams of doing. In her 1861 memoir Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, she writes:

A clergyman who goes to the south, for the first time, has usually some feeling, however vague, that slavery is wrong. The slaveholder suspects this, and plays his game accordingly. He makes himself as agreeable as possible; talks on theology, and other kindred topics. The reverend gentleman is asked to invoke a blessing on a table loaded with luxuries. After dinner he walks round the premises, and sees the beautiful groves and flowering vines, and the comfortable huts of favored household slaves. The southerner invites him to talk with these slaves. He asks them if they want to be free, and they say, “O, no, massa.” This is sufficient to satisfy him. He comes home to publish a “South-Side View of Slavery,” and to complain of the exaggerations of abolitionists. He assures people that he has been to the south, and seen slavery for himself; that it is a beautiful “patriarchal institution;” that the slaves don’t want their freedom; that they have hallelujah meetings, and other religious privileges.

[7]

[7]You can buy Spencer J. Quinn’s Solzhenitsyn and the Right here [8].

Fair enough; A South-side View of Slavery hardly abides by the highest standards of scholarship. But clearly such cursory invective does little justice to Adams’ conscientious approach. Further, similar criticisms could be levied against Jacobs as well. She says quite a few racist and incendiary things about whites in her book. How do we know she wasn’t making some or even all of her claims up? How do we know her abolitionist friends didn’t convince her to fudge the truth a bit for the cause?

The very best part of A South-side View of Slavery occurs near the end, when Adams offers proof that his fellow abolitionists are really just a group of narcissistic virtue-signalers who do far more harm than good. In demonstrating that the worst of American slavery was nevertheless better than what was experienced by the miserable masses in the great Northern (and English) cities, he shares several accounts of exquisitely painful white suffering that his high-minded colleagues hadn’t thought worthy of adding to their view of the sum of all villainies — and this was happening right under their noses in the very cities where they lived.

His rebuke to these people is beautiful:

No chains about the Court House prevent you from interposing as bail for the tempted souls in their first step into crime; no Mason’s and Dixon’s line makes a boundary to your lawful zeal. These poor ye have always with you, and when ye will ye may do them good. If the saying is true, that a man who goes to law should have clean hands, he who reproves others for neglect and sin should be sure that the God before whom he arraigns them can not wither him by that rebuke, “Thou hypocrite! first cast out the beam out of thine own eye!”

Where I go that Nehemiah Adams does not, however, is to extrapolate from slavery the real reason behind the deadly disconnect between North and South — which is race. White slaves — or white coal miners, white factory workers, or other poor whites who may as well have been slaves at the time — would not, and indeed did not elicit as much ardor from these abolitionist do-gooders as black slaves hundreds miles away who were surviving, and in many cases thriving, within what was perhaps the mildest form of slavery at the time.

The European powers of the day allowed white slavery to go on in North Africa for centuries [9] before getting serious about stopping it [10]. In many cases, white slaves in Barbary had it far worse than blacks in the antebellum South. Yet, over and over again white leaders preferred diplomacy, flattery, and bribery to the costly but effective use of their militaries to end the problem. Where were the abolitionists then? White people were just as Christian in 1554 as they were in 1854, so why did they start beating the war drums only after black slavery appeared in the New World? What else was there to their moral equation besides race and the desire to virtue-signal over an outgroup?

If anything, Nehemiah Adams’ A South-side View of Slavery demonstrates the bankruptcy and hypocrisy of those radical abolitionists who did more to start the bloodiest war on American soil than anyone else. It unveils the sham that was — and still is — the virtue-signalers’ anti-white posturing. And sadly, it underscores the tragic flaw in the white mind: We try so hard to appear to be good that we forget the most important thing: that we already are.

* * *

Like all journals of dissident ideas, Counter-Currents depends on the support of readers like you. Help us compete with the censors of the Left and the violent accelerationists of the Right with a donation today. (The easiest way to help is with an e-check donation. All you need is your checkbook.)

For other ways to donate, click here [11].