Of Donkeys and Men: A Review of The Banshees of Inisherin

Posted By Angelo Plume On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledMany years ago, in what now seems to be almost like a past life, I used to be quite the cinephile. I loved films. I loved the French Nouvelle Vague. I loved Italian neorealismo. I became enamoured of the great auteurs. On many occasions, I would drive to faraway cinemas in the big cities so I could see films—usually foreign or independent ones—that were not going to play in my hometown movie theatres. When I was even younger, I used to eagerly await the the Friday edition of the local newspaper so I could read the movie reviews of the weekend’s new releases. When I reached my college years, I took a few elective courses on film history and production.

Nowadays my burning passion for the silver screen has been reduced to grey, dusty ashes. It is a fate that has befallen many people, I’m sure, and it is a sad indictment of our modern society. If we look at the Hollywood balance sheet for 2022, it’s clear that even the general population has been put off by what’s on offer these days. This is a shame. It’s not right that we should be bereft of the wondrous form of art that is film, that we should be robbed of the joy and the spiritual and intellectual stimulation that well-made stories told on celluloid can give. Therefore it is with great pleasure that I can recommend a contemporary film which I recently saw and was happily surprised to discover that it does indeed give the viewer that gift of joy and stimulation, and entertainment, without being infested with propaganda and pandering to “modern audiences”.

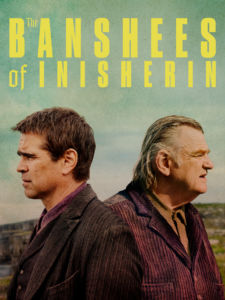

The film is The Banshees of Inisherin. This is a film that does not try to appease a broad audience, although it certainly can. It is unabashedly and exclusively Irish. That’s not to say non-Irish folk won’t like or understand the film (well, some accents might indeed be hard to understand), but the film is quite clear that it intends to be a story for Irish folk by Irish folk. I love that. It reminds me of those French and Italian films I devoured in my youth. The Banshees of Inisherin, like those films of old, is set in a distinct place, it tells a distinct story for and by a distinct people. And yet, as is often the case, some of the most particular stories end up having the most universal appeal. The Banshees of Inisherin certainly has proven that again, garnering 9 Oscar nominations as well as a positive audience rating on Rotten Tomatoes.

It opens with some of the most spectacular shots of the wild coast of Ireland. Inisherin is itself a fictional island off the mainland, so what cinematographer Ben Davis and director Martin McDonagh show us in these first moments are actually the sights of the Aran Islands and Achill Island. If the opening sequence of these landscapes, lightly brushed with strokes of an ethereal gilded haze, don’t make you want to catch the next flight to Ireland, you might not have a soul.

The drama begins when Pádraic (pronounced Paw-rick), played by Colin Farrell is devastated after his life-long friend Colm, played by Brendan Gleeson, informs him that their friendship is over. I think I’ve always had a higher opinion of Farrell than most, because I know what Farrell is capable of under the direction of Martin McDonagh. Farrell, an actor blessed with the most expressive and mobile eyebrows, has done some of his best work in the two other McDonagh films in which he starred: In Bruges and Seven Psychopaths. Here he is on fine form again. When Colm informs Pádraic that he no longer wants to be friends, there is a moment in which Farrell gives us a wordless performance that is befitting of a silent film star limited to the use of his facial expressions to convey his character’s turmoil.

Brendan Gleeson is brilliant, as usual. Imposing and commanding, there is something about Gleeson’s very physicality that means he will always dominate the frame. It’s not because he is a large man, although that he is. His weight is not just corporal. There is a heaviness in his eyes, in the furrows of his brow. When he is on screen, you feel the burden of despair he confesses to the local priest.

Why is Colm despairing? Because he wants to accomplish something before his time is up. He wants to achieve immortality by creating a piece of music for which people will remember him long after he is gone. The small talk and chit-chat with Pádraic about farm animals and the marvels that can be discovered in their excrement no longer suffice for him. He needs peace and quiet, time to be alone and focus on composing. Pádraic just doesn’t fit into that need.

Peace and quiet are certainly not lacking on the island of Inisherin. There are many metaphors and themes in this film. An obvious one is the tale’s very setting: Ireland, 1923. The civil war between the Irish Free State and the Irish Republican Army is grinding to a halt, but still raging. The sudden, painful, explicable (Colm explains his reasons many times), but incomprehensible rupture between Colm and Pádraic represents the civil war boiled down to just two Irish men. The other themes that Banshees explores, and that most resonated with me, however, are loneliness, the desire to do something worthwhile with your time, and the notion that the grass is always greener somewhere else.

[2]

[2]You can buy Trevor Lynch’s Classics of Right-Wing Cinema here [3].

You see, it’s not that Colm wants to leave Inisherin because he finds it dull. He finds Pádraic dull, and probably everyone else on the island, too. But he doesn’t seem to harbor much will to leave. He has a nice house on the beach, a loyal dog, and his music. He wants peace and quiet, and apart from Pádraic, Inisherin provides that.

It is Pádraic’s sister Siobhan (Sheh-VAWN), portrayed by Kerry Condon in a scene-stealing performance, who wants to get away. “You live on a tiny island off the coast of Ireland,” she tells Colm when he admits to her that he deems her brother too boring and life too meaningless. “What do you expect?”

Siobhan has obviously been making plans for a new life on the mainland, in the big city. These plans come to fruition when a life-changing opportunity arrives to her via post. Even though she has been planning for this change, she still has to deliberate carefully. Can she really abandon her brother, after his best friend has just forsaken him too? The peace and quiet may be fine for someone like Colm, and for a nice but rather simple man like Pádraic, Inisherin is a lovely place. But Siobhan is clever and well-read, and not getting any younger. She’s tired of impish lads asking her why she never married. She’s tired of playing hostess for old hags who want to come round and gossip. She needs something more.

It is a very compelling juxtaposition. On the one hand, we have an idyllic Irish village surrounded by Atlantic beauty that only divine beings could create. Many people living in a city, especially the modern concrete-and-steel jungles of today’s megalopolises, would gladly relocate to Inisherin. Yet Siobhan, an Inisherin native, wants nothing more than to leave the island and move to the city (albeit the Dublin, or any of Ireland’s other major cities, of 1923 would not have been the ugly little Londons, full of skyscrapers and “diversity,” that they are now).

In the end, Pádraic finds himself utterly alone. His best friend wants nothing to do with him. His beloved sister has moved on and moved off the island. He is left with no one but the “touched” Dominic. Dominic is touched not just in the head. His life is one of torment borne in silence. Not everything on Inisherin is pure and idyllic. At one point, Pádraic can no longer bear it and he becomes something he really isn’t. Or maybe he is? After several shots of whiskey give him the courage, if not the eloquence, to challenge Colm, Pádraic is heartened by false hope when he learns that Colm absolutely loved the brutal honesty that poured like that same whiskey from Pádraic’s drunken mouth. So Pádraic adopts a new personality. No more Mr. Nice Guy. This change disappoints and even horrifies Dominic, who decides that he, too, wants nothing more to do with Pádraic.

In the following scenes when Pádraic is now utterly friendless, we feel the cold loneliness of rural life. Pádraic is lonely because he has no one in his life anymore, apart from his farm animals, especially his cherished miniature donkey Jenny. Meanwhile, Colm is alone because he cannot relate to anyone in town. Colm is the kind of person who could feel lonely at a party full of happy people: the brooding artist. The viewer can only hope that Siobhan finds what she’s looking for in the city, but the lesson of whichThe Banshees of Inisherin reminds us is that you can go abroad, and you can change city for countryside or countryside for city, but your own personal failings and shoulder-riding demons will always haunt you. There are certain places where you might feel more at home, more at ease, and more fulfilled, but while you can get away from the dirty city or the boring village, you can never get away from yourself. It’s worth remembering that.

The Banshees of Inisherin, like McDonagh’s other films In Bruges and Seven Psychopaths, is a “dark comedy” or a “tragicomedy.” Some have criticized the film for being insufficiently comedic or dramatic. It’s true that McDonagh does not indulge in gore, even though he could easily have done, and perhaps that would have increased the tension, but the story does, in my opinion, reach Sophoclean levels of tragedy. There are several moments of mirth, too, especially if you have an appreciation for Irish wit and banter.

As for propaganda or subversion, I’m happy to say that Banshees is almost entirely free of both. There is a hint of anti-Catholic sentiment which may or may not annoy some viewers, but aside from that there is no “poz” to speak of.

Not that I have seen many new films over the past year but for what it’s worth this, alongside The Northman, has been the standout film of 2022 for me. I do recommend you see it. 4 out of 5 stars.

Reprinted with permission from Pox Populi’s Substack [4].

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “Paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

- Third, Paywall members have the ability to edit their comments.

- Fourth, Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected] [5]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[6]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[6]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.