John Wayne’s The Alamo & the Politics of the 1960s

Posted By Morris van de Camp On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledSee also: John Wayne [2]

Oh, Almighty God, centuries ago thou raised a magnificent Mission, a harbor for all of peace and freedom. This was the Alamo. Today we ask thy blessing, thy help, and thy protection as once again history is re-lived in this production. We ask that this film, The Alamo, be the World’s most outstanding production. We ask this in the name of Our Lord, Jesus Christ, who lives and reigns world without end. Amen. — Invocation recited on the first day of The Alamo’s production

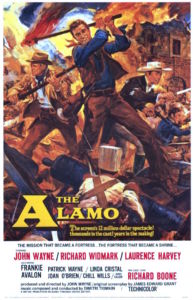

The Alamo (1960), produced, directed, and starred in by John Wayne, is a movie whose artistic merit is difficult to quantify. It is an outstanding film with a lasting legacy, but not a masterpiece or even a flawed masterpiece. Audiences lined up to see it upon its release, although it was nevertheless not profitable because its production costs were so high. It was ten years until the last of its financial backers broke even.

[3]

[3]The Alamo Cenotaph in San Antonio. The three colonels were William Barrett Travis, Jim Bowie, and David “Davy” Crockett. The Alamo’s defenders were at a disadvantage due to the divided command structure.

In the 60 years since its release, assessments of The Alamo have remained consistent: Most critics hold that it is too slow and has too much dialogue, much of which was concerned with the idea of “freedom” that was at the center of political debate in America in the early 1960s. There are many excessively long speeches on government and a free society. A subplot about a romantic interlude in which Davy Crockett (John Wayne) helps Flaca (Linda Cristal [4]) in a domestic dispute with a suitor is also superfluous. But despite all its flaws, the film made a lasting impact on American culture. It was nominated for seven Oscar awards, but only received one, for Best Sound [5].

On the positive side, the battle scenes are excellent, and it has a top-notch musical score [6]. Its cinematography is likewise brilliant, such as when we see deer bounding out of the brush as horsemen ride up on them; and men crossing a river as mist rises and dancers perform in the background, ethereally lit. And the scenes depicting the Mexican army were so well-made that they were reused in How the West Was Won [7] (1962).

The Battle of the Alamo

Michael Walsh writes the following about the Battle of the Alamo in his book about last stands [8]:

What was it about the Alamo that changed the history of the American southwest? Militarily, its importance was minor; just another fort to be conquered and re-subsumed into sovereign Mexico. The Mexicans had made the fatal mistake — as the Romans had a millennium and a half before — of inviting in foreigners from an antithetical ethnicity, faith, language, and culture and allowing them to flourish and supersede the natives in population and thus overwhelm them by sheer force of numbers — enhanced, of course, by considerable cultural and political animosity. Diversity, it seems, was of as little use to the Mexicans as it was to the Romans in the fifth century. There was no “strength” in it, only trouble.[1] [9]

The Battle of the Alamo, which took place in San Antonio between February 23 and March 6, 1836, was part of a larger war between the Anglo-American settlers in the then-Mexican state of Texas and the Mexican dictator Antonio López de Santa Anna, who is commonly called “Santa Anna.” The Texas War of Independence was an ethnic conflict between primarily Scots-Irish American Protestants and Tex-Mex Spaniards [10] on the one side, and a (nominally) Catholic aristocracy of Spanish origin from central Mexico and the Mestizo peasantry on the other. The war was framed by its participants as a fight over differences in civic ideology. Its origins lay in Santa Anna becoming the dictator of Mexico and suspending the country’s constitution in 1824, followed by a crisis in Texas triggered by events in central Mexico in 1835.

The Anglo-Americans in Texas were shocked by the constitution’s suspension and decided to secede from the failing state of Mexico. A detachment of the Texan army fortified the old Spanish Mission at San Antonio, which was called the Alamo. The Alamo had three commanding colonels during the battle: William Barrett Travis [12], Jim Bowie [13], and David Crockett [14]. Crockett was a former Congressman from the Whig Party, which was opposed to President Andrew Jackson. His rank was more of an honorific, as he had only really wanted to be a “high private.” But as a legend in his own time, the rank was forced upon him in the midst of a desperate situation.

The Alamo was then besieged by the Mexican army, which was under the command of Santa Anna himself, and the defenders were killed to the last man. After their victory, the Mexican army then moved deeper into Texas and was destroyed when they were attacked by the Texans while taking a siesta at San Jacinto [15]. Santa Anna was captured by the Texan army during the battle, and in brief was compelled to sign a peace treaty that granted independence to Texas.

John Wayne’s The Alamo has little connection to the actual historical facts, however. The most important difference is that the battle wasn’t in fact a fight for “freedom,” but was really an ethnic clash that tangentially involved some differences over civic ideology. The historian Mary Deborah Petite [16] gave a more detailed account of the differences between The Alamo and the actual battle in a lecture on CSPAN [17] in 2000.

[18]

[18]The War for Texan Independence was the result of a fatal mistake by the Mexican government, as they had allowed foreigners from an antithetical ethnicity to supersede their native population through immigration.

The Battle of the Alamo in film and culture

The Alamo became the definitive film about the battle. The story is an Indo-European last-stand epic [19], and its story was destined to be immortalized as soon as the facts about it became known across the United States in 1836. It is therefore not surprising that the battle ended up being the subject of several Hollywood films. The first such film was The Immortal Alamo [20] in 1911, which has unfortunately been lost. D.W. Griffith then produced The Martyrs of the Alamo [21] in 1915.

Walt Disney produced an entire TV series in 1954 entitled Davy Crockett which starred Fess Parker [22] as the eponymous hero. Three of the episodes were repackaged into a movie in 1955 entitled Davy Crockett: King of the Wild Frontier [23], which concludes with Davy Crockett being killed in action while valiantly swinging his rifle at the Alamo [24].

Disney’s Davy Crockett created a nationwide coonskin cap fad. Raccoon coats which had been sitting in warehouses since they went out of fashion in 1929 were remade into caps, and they became a symbol of the Boomer generation’s childhood. This fad helped to inspire wider interest in American history and reenactments of various events [25], including the Alamo most especially. John Wayne’s film capitalized on this trend.

[26]

[26]Young Americans gathering at the Alamo in 1955, wearing coonskin caps. (Images of Texas History — Robert Blankenship)

Leadership in The Alamo

The Alamo is a study in leadership. It was John Wayne’s directorial debut, and he did a tremendous job. He had the set built in the middle of nowhere. His company sunk wells and built an airstrip to accommodate the location. Wayne also hired a man who’d been a Non-Commissioned Officer in the Marine Corps teach the Mexicans playing the soldiers of Santa Anna’s army how to march and conduct close-order drills. The effort paid off, as is clear in the well-choreographed battle scenes, which feature entire regiments of extras.

The film’s three stars demonstrate three different styles of leadership. Richard Widmark portrays Bowie as a rough-and-tumble man who best represents his group’s mores and leads by example. John Wayne’s Davy Crockett offers leadership by consensus, using charm, logic, and outright manipulation to compel his followers to arrive at the same conclusions he has already reached. Laurence Harvey plays Travis as a by-the-book, aloof leader, a style best practiced the older one is and the higher one’s rank is. At a certain point, you can’t just be one of the boys.

[27]

[27]From left to right: Richard Widmark as Jim Bowie, John Wayne as Davy Crockett, and Laurence Harvey as William Travis.

The Alamo and the politics of the 1960s

They never shut up. No wonder they lost — the Mexicans could have come over the walls while they were all talking. But Granddaddy wanted to get his points across, and it was his picture, and he could do what he wanted. — Gretchen Wayne, John Wayne’s granddaughter[2] [28]

The Alamo was meant to be political from the outset. Its message focused on the importance of traditional values and patriotic civic duty, directed at Americans in the midst of the then-ongoing Cold War. Many of the film’s most passionate supporters were energized by its message. 1960 was an election year, and Russell Birdwell [29], a Hollywood publicist who was one such passionate supporter, took out an advertisement in Life Magazine on July 4, 1960. It read:

Very soon, the two great political parties of the United States will nominate their candidates for president. Who are these men who seek the most formidable job, the most responsible job on Earth? There is a growing anxiety among the people to have straight answers. They wait impatiently as the Free World becomes smaller for a return to the honest, courageous, clear-cut standards of frontier days. The days of America’s birth and greatness. The days when the noblest utterances of man came unrehearsed. There were no ghost writers [i.e., hack political writers] at the Alamo — only men.

Birdwell’s advertisement was perceived by Harry Truman as a plug [30] for then-Senator Lyndon Baines Johnson to become the Democratic nominee. LBJ appeared to be a segregationist conservative in 1960. John Wayne was a Republican, and it is easy to infer that the Life advertisement was in part a not-so-subtle hint that the Republican, Richard Nixon, then Dwight Eisenhower’s Vice President, should be the next man for the job. Wayne likewise consulted with conservative Democrat John Nance Garner [31], who had been one of Franklin Roosevelt’s vice presidents, before making the film.

[32]

[32]You can buy Greg Johnson’s The Year America Died here. [33]

The Alamo was a means of encouraging Americans to stand strong during the Cold War with its emphasis on military virtue and the “clear-cut standards of frontier days.” The remarks in the Life advertisement about the “Free World [becoming] smaller” also emphasized the genuine fear that was prevalent at the time, all the more since the Communist Fidel Castro had just recently come to power in Cuba.

In terms of “civil rights,” Texas’ honor had recently come under attack in the 1956 movie Giant [34], based on a novel by Edna Ferber, an ethnonationalist Jew. In Giant, the issues surrounding segregation were presented through an artistic exploration of the ethnic differences between Anglos and Mexicans in rural Texas. The use of Mexicans as a proxy for sub-Saharans was an act of disingenuous sleight-of-hand. There was no “Hispanic” racial category in the 1950s, and Mexicans were considered white by the US Census Department. John Wayne was able to persuade Texas businessmen to invest in his film by promising to counter the negative image of Texas that had been promoted by Giant.

The Alamo attempts to blend “civil rights” and Cold War patriotism with colorblind civic nationalism and veneration of military service. There are two sub-Saharans in the story, one of whom is a child who plays Travis’ slave. He leads the women and children out of the fortress at the end of the film in a portrayal of honest and faithful service.

The more important role, however, is that of Jethro (Jester Hairston [35]), who plays Bowie’s slave. In all the legends of the Alamo, there is always a “crossing of the line” event where Travis is said to have given the defenders the option to retreat with honor after it becomes clear that the battle cannot be won. Travis is said to have drawn a line in the sand with his sword, telling those who crossed the line that they were committing to fight to the bitter end, while those who didn’t were free to leave.

The Alamo of course also includes this scene, although without the usual line drawn in the sand. Jethro is the second person to “cross the line,” after Bowie. He also also gets a beautiful death scene [36], throwing himself in front of the Mexican bayonets in order to allow Bowie to begin wielding his famous knife before he, too, is killed. Jethro’s scenes are embarrassingly corny, but they demonstrate the colorblind ideals of Cold War-era military service. Around the time the film was made, the recently-integrated American armed forces were already on the path to becoming violently problematic. For example, in 1962 Robert F. Williams, a sub-Saharan “civil rights” activist who was making pro-Castro broadcasts from Cuba, encouraged African servicemen to carry out an insurrection during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Nothing came of it, but by the end of the 1960s sub-Saharan troops were causing problems everywhere they were posted, just as has been predicted by the segregationists.

Another political moment in the film is when Wayne pushes the “aggression at Munich [37]” theory of international relations, which was a common trope in the early 1960s. In this view, “aggression” anywhere in the world has to be stopped using military force as soon as it appears in order to defend “freedom.” The dialogue is as follows:

Tennessean (Denver Pyle [38]): I only know part of Texas, and none of these Texicans is related to me. So why should I fight for them?

Another Tennessean: Right. Ain’t our ox that’s gettin’ gored.

Davy Crockett: Talkin’ about whose ox gets gored . . . Figure this. A fella gets in the habit of goring oxes, whets his appetite. He may come up north next and gore yours.

The Alamo likewise celebrates traditional sexual values. For example, the film’s central song, “The Green Leaves of Summer [39],” includes the following lines,

A time just for plantin’, a time just for ploughin’

A time to be courtin’ a girl of your own.

‘Twas so good to be young then, to be close to the earth,

And to stand by your wife at the moment of birth.

In other words, the purpose of dating a woman is to find the one to marry and have children with. The sexual revolution [40] was already underway by 1960, so the song was perhaps addressing that. We see a hint of this as well during the romantic interlude where Crockett attempts to rescue Flaca, the damsel in distress. She says:

Would you so quickly offer to defend me if I were 60 years old and wrinkled? Or is it because I am a young and a widow, and you are far from your loved ones?

Politics on set

The Alamo’s political messaging impacted relationships on the set. Most of the stars had an ancestral connection to the age of frontier expansion. Richard Boone, who plays Sam Houston, was not descended from Daniel Boone, but he was part of Boone’s family, and his ancestors had been pioneers in frontier Missouri. John Wayne was descended from a Union Army soldier who later worked in California real estate during the late stages of that state’s Anglo-Midwestern settlement. Laurence Harvey was Jewish and had grown up in Johannesburg, South Africa — a city that then had a recent frontier history – before moving to England.

Harvey and Boone had served in the Second World War, in the South African army and US Navy, respectively. Widmark and Wayne had not served in the conflict, but their brothers had. Widmark’s brother was shot down over the Netherlands and spent time in a prisoner of war camp. Many of the high-testosterone Westerns and war movies [41] of the early 1960s starred men who were playing roles that drew from experiences they had had in wartime, and The Alamo was no different.

All these men were tough. When a cannon rolled over Harvey’s foot, crushing it, Harvey stayed in character and didn’t react until after Wayne called “cut.” Harvey then wrapped his foot and kept acting. He and Wayne got along well together; Wayne jokingly called him an “English fag.”

Wayne had originally wanted to play Sam Houston so he could focus on directing, but the film’s backers insisted that he play a more important character since he was a reliable box-office draw. But Wayne is miscast as Crockett. Wayne tried to get James Arness of Gunsmoke to play Houston, but Arness didn’t show up to a scheduled meeting to discuss his role. Why this happened is uncertain, but it could very well that he disliked the film’s political overtones.

Widmark was a liberal Democrat. He supported “civil rights” and had starred in No Way Out [42] (1950), directed by a Jew, Joseph L. Mankiewicz. No Way Out features all the basic anti-white themes that are commonly seen today. Widmark and Wayne did not get along. While they remained professional during filming, they quarreled between takes. It is very likely that their different views on “civil rights” were part of the problem. While Wayne was not a segregationist, he believed that non-whites should integrate into American society according to white standards.

The Alamo’s legacy

Republic! I like the sound of the word. Means people can live free, talk free, go or come, buy or sell, be drunk or sober, however they choose. Some words give you a feeling. Republic is one of those words that makes me tight in the throat. The same tightness a man gets when his baby takes his first step or his first baby shaves and makes his first sound like a man. Some words can give you a feeling that make your heart warm. Republic is one of those words. — Davy Crockett in The Alamo

Given that The Alamo depicts the battle as being a fight for “freedom” as opposed to an ethnic conflict, it was not criticized for its politics at the time of its release. The values the film celebrates were widely seen by most Americans at both ends of the political spectrum as being necessary for winning the Cold War. The difference between the film’s portrayal of the conflict and its reality is evident in the changes that were made. For example, while the actual siege at the Alamo was occurring, Sam Houston was drafting the constitution for an independent Texas, while in the film, he is busy raising and training an army, saying [43]:

Now, tomorrow, when your recruits start to whine and bellyache, you tell them that 185 of their friends, neighbors, fellow Texicans are holed up in a crumbling adobe church down there on the Rio Bravo, buying them this precious time.

Metapolitics is more important than military virtues. Texas won its independence in no small part because its leaders first formulated their new government’s form and then fought. Fighting alone isn’t enough when the goals motivating it are unworkable, such as what happened when the US went to war in Vietnam.

During the January 6 protest, many of the participants wore fur caps [44] similar to those of the Tennesseans in The Alamo. It seems that some of them saw their own struggle as not being unlike that of the Texans against the dictatorial Santa Anna. The film’s use of history as a way to comment on today’s politics is thus perhaps the film’s longest and most important legacy.

* * *

Like all journals of dissident ideas, Counter-Currents depends on the support of readers like you. Help us compete with the censors of the Left and the violent accelerationists of the Right with a donation today. (The easiest way to help is with an e-check donation. All you need is your checkbook.)

For other ways to donate, click here [45].

Notes

[1] [46] Michael Walsh, Last Stands: Why Men Fight When All is Lost (New York: Saint Martin’s Press, 2020), p. 190.

[2] [47] Scott Eyman, John Wayne: The Life and Legend (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2014), p. 316.