A “Novel” Approach to the Understanding of Evil

Posted By Stephen Paul Foster On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled3,236 words

The heart is deceitful above all things, and desperately wicked: who can know it? — Jeremiah 17:9

Unde malum? Where does evil come from? I first pondered that question as a child, a childhood of full immersion in a fundamentalist, Baptist Weltanschauung. Evil’s origin and its persistence in the world was the central motif in the narrative of the Great Rebellion, the failure of Angel Lucifer’s insurrection against God. The origin of evil came from a titanic battle of supernatural beings. That conflict continued to played itself out in the struggle of individual human beings to resist sin, sin being participation in evil encouraged by the Devil in his ongoing guerilla warfare campaign against God.

He that committeth sin is of the devil; for the devil sinneth from the beginning. For this purpose the Son of God was manifested, that he might destroy the works of the devil. — 1 John 3:8

Lucifer’s rebellion and its application to man’s irresolute intentions to be good and eschew the temptation of the Devil held my attention as a child and made the challenge of resisting sin a serious preoccupation.

However:

When I was a child, I spoke as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things. — 1 Corinthians 13:11

I became a man before “manhood” was rendered just one of many options, and put away “the Devil,” so to speak. But evil was hardly a childish thing. It was persistently, unavoidably real. It had to be explained, not mythologized. Where did it come from? How was it possible for evil to persist if there was a God — the Christian God from my childhood — who was omniscient, omnipotent, and omnibenevolent? An omniscient God would know there was evil in the world. If he is omnipotent, he could eliminate it; and as omnibenevolent, he would be so compelled.

Logically, this was the theo-philosophical elephant in the room for a Christian theist. Back then I liked to think of myself as possessed of a cool, intrepid personality, intellectually equipped and willing to go mano a mano with the elephant-intruders, no matter where the theorizing might take me — even to the City of no-God [2], which for a Baptist in flyover country is still considered a bridge too far.

I soon discovered that theorizing devoted to the “elephant problem” had a name: “theodicy,” given to it by Wilhelm Gottfried Leibniz [3]. Theodicy [4]: the reasons offered to explain “why a perfect being does or might permit evil of the sort (or duration, or amount, or distribution) that we find in our world to exist.”[1] [5] The coexistence of God and evil was an aporetic problem and a huge preoccupation for Leibniz. Theodicy was the only treatise of book length published during his long lifetime.[2] [6]

Leibniz’s herculean efforts at theodicy centered on two problems related to how God and evil can coexist. The first is what has come to be called the “underachiever problem,” which led the Socinians[3] [7] to conclude that the undeniable existence of evil in the world called God’s omniscience into question, making his creation imperfect, and thus an “underachievement.” The second was the “holiness problem,” which given God’s authorship of all of creation including man would make him complicit in the occurrence of evil, a negation of his goodness.[4] [8]

The underachiever and holiness problems could be dispensed with by the atheist argument that the abundant evidence of evil in the world makes it logically impossible for a Christian God with omni-attributes to coexist with it. Proof by the law of contraposition [9]: The conditional, if E (evil in the world) then ˜G (no God exists) converts to its contrapositive, if G (God exists) then ˜E (no evil in the world). Either God or evil — but not both.

Being a Christian theist, the atheism direction was not an option for Leibniz, thus the lifetime devotion of one of the great minds of Western philosophy to the creation of a philosophical edifice that would keep the God of Christianity intact while simultaneously recognizing the reality of evil: “The best of all possible worlds.”

The Western world’s secular turn that followed Leibniz would leave theodicy as an important chapter in the history of Western philosophy on its journey to making the existence of God philosophically superfluous. Supernaturalism’s portly demolitionist, David Hume [10], had Leibniz’s Essais de Théodicée in mind when he wrote the Dialogues on Natural Religion.[5] [11]

[12]

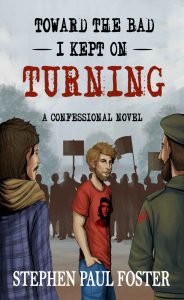

[12]You can buy Stephen Paul Foster’s novel Toward the Bad I Kept on Turning here. [13]

What about evil?

In my simplified typology, explaining evil without God in the picture moved in three most unfortunate directions in modern Western thinking: the Rousseau and Marx versions, and the progressive-liberal version.

For Rousseau, “original sin” came about when “[t]he first man who, having fenced off a plot of land, thought of saying, ‘this is mine,’ and found people simple enough to believe him, [and he] was the real founder of civil society.”[6] [14]

Evil’s origin was the exertion of power that created private property, thus making society into a collective of haves and have-nots — collectivized inequality, the source of human conflict and misery. Evil was a human creation that human beings themselves had the power to undo. The French Revolution launched by Jacobins was inspired by Rousseau: liberté, égalité, fraternité.[7] [15] It was in essence a moral crusade conceived by anticlerical intellectuals riled up about an abstraction: inequality. Its concretized target, the ancien régime with its embodied hierarchies, was the perpetuator of inequality and the source of evil. As encyclopedist Denis Diderot is said to have put it: “Man will never be free until the last king is strangled with the entrails of the last priest.” The Rousseau-ist answer to inequality, in a word, was “democracy.”

The Marxist answer to inequality in a word was “Communism.” Marx, like Rousseau, secularized the source of evil as inequality, but his understanding of it was derived from a philosophy of history influenced by Hegelian dialectics [16]. “The history of all hitherto existing societies is the history of class struggles. [17]” Inequality results from society’s ruling class imposing its values (ideology) on the underclass. For society to rid itself of evil, the ruling class, the perpetuating force of inequality, had to be overthrown. Marx’s conflict-premised history was moving, dialectically, towards a happy ending with an inevitable conflagration that would finally produce a classless society, thus free of inequality — the source of evil. “From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs” was the operative formula in a truly egalitarian society that would sustain the victory of good over evil.

Rousseau led to Napoleon. Class struggle-based Marxism put into practice became Stalinism, which proved to be catastrophic; a showcase for a uniquely vicious and lethal, new type of oppressor class. However, the inequality = evil formula was picked up and carried forward by progressive-liberals. Equality for the progressive-liberal is the natural state of human beings — individuals as well as the various groupings. The inequality that we encounter daily and that seems so much a permanent fixture of things is really historically contingent on certain human practices that can (and should) be disposed of — racism, sexism, homophobia, etc. — by progressive-minded people. “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice [18]” is a line of progressive poetry favored by the likes of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Barack Obama, the “bending toward justice” metaphor symbolizing the movement toward equality. The “moral universe” envisioned is a deracinated world of empowered victim-class members taking revenge [19] on their oppressors.

Since the source of inequality is these malignant human “ist” and “obia” practices, their exorcism turns out to be a kind of moral reengineering challenge using pest-control technologies to eliminate the “pests”: racists, sexists, and the like. These pests perpetuate inequality and inhibit the “bending of the arc”: progress. Think of liberal-progressive “progress” as the ongoing pest-removal with a never-quite-attained end-state of perfect equality and the disappearance of evil.

The view of evil as being the result of supernatural agency I held as a child is benignly mythological in its function as an allegory that captures the perennial human moral struggle to overcome the temptations of wickedness. The Rousseau-Marx/progressive-liberal equation of inequality = evil, however, is perniciously mythological because it is surreptitiously superstitious. Natural equality is an appealing myth forced to masquerade as a true feature of the human condition deviously subverted by the wrong sorts of people. This superstition remains the foundation of an aggressive, utopian ideology that operates in opposition to reality. It also operates to demoralize [20] people who resist the masquerade.

Many years ago, my own philosophical interest in the nature of evil turned disturbingly, intensely personal by virtue of a sustained encounter with an evil person.

If men are friends, there is no need of justice between them. — Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics

The evil person was someone who had been my close friend for 15 years; someone who, I would discover, had brutally, sadistically murdered two young women, both girlfriends who had rejected him. The details are captured in an entry on a blog [21] I no longer maintain.

My friend, whose name was Bill, was not your typical loser who works himself into a violent temper and up and slays his defenseless girlfriend. This particular slayer turned out to be a man of advanced degrees, sophisticated tastes, serious books, and immense erudition. Fluent in four languages, the range and depth of his knowledge was phenomenal. He could converse insightfully about the influence of Kantian ethics on German legal positivism, help you fathom the aesthetics of Arnold Schoenberg’s atonalism, and substantively compare English translations of the pre-Socratic philosophers. His personality was big, engaging, and charming. He was outrageously funny, often boisterous and dramatic, and he injected energy and life into almost any gathering in which he found himself. My wife adored him, and he was delightful with my daughters. The homicide detective I spoke with shortly after the second slaying told me it was the most brutal killing that he’d witnessed in his 20 years on the force. It made national news [22]. It was unthinkable to me that my friend could have done it.

[23]

[23]You can buy Stephen Paul Foster’s new novel When Harry Met Sally here. [24]

Bill’s murders were 19 years apart. The second one took place in Florida. I did not know about the first one until after the I learned of the second. He died on death row by suicide. [25]

The discovery of this dark side in a close friend was a shattering ordeal, and put me on a mission to better understand the nature of evil. The relationship with him had left me feeling complicit. How could I have not seen the evil in this man? What could be made of it?

After meditating for years on the circumstances of this friendship, I recently completed a novel,[8] [26] a fictionalized version of our relationship, the murders, and the second trial. It turned into a set of moral and philosophical reflections of the novel’s main character after the discovery that his friend was a closeted monster.

Writing the novel led me to a view of evil that began with Jean-Jacques Rousseau and ends with T. S. Eliot’s observation that Rousseau [27] “has proved an eternal source of mischief and inspiration.” Yes. This mischief is displayed in a sentence from the Social Contract that captures the folly of a Romanticism that has hardened into the permafrost of Western Left-wing ideology: the worst of us is somehow fixable. “‘There is no man so bad that he cannot be made good for something.”[9] [28] No. The immense effort I had spent meditating on this one man as some kind of self-contained, mysterious immoral entity apart from the rough and tumble grubbiness of humanity had been a fool’s errand.

The paradox of my friend’s life — a gifted mind, a corrupt personality, a true friend, a devious manipulator — finally gave way to an epiphany that unfolded with the application of Occam’s Razor: “What can be done with fewer assumptions is done in vain with more.” Simplicity in the form of the fewest assumptions possible was the best way to understand the evil in this man and in others. One and only one assumption was sufficient: Some people are just no good. My friend was in that category; he was no good. Contra Rousseau, he could not be made good for anything.

In his trial for the second murder, to convince the jury that Bill’s torture and killing[10] [29] of his girlfriend was not a first degree (capital) murder, his attorneys summoned as defense witnesses “theorists of the mind” — psychologists — to compound the “assumptions” that would explain Bill’s evil; abstractions conjured out of the black box of “mental health” in the form of “disorders.”

By undo profundity, we perplex and enfeeble thought. — Edgar Allan Poe, “The Murders in the Rue Morgue”

The trial was a formal ritual of “undo profundity.” It attempted to factor in of all of Bill’s personal paraphernalia that had been relevant to the murder. But pondering his potential, intelligence, educational attainment, cultured charm, and his sick, unhappy childhood with divorced parents and a callous father was worse than useless as an effort to explain the elusive why he did what he did. Some people are just no good. It is that simple. They are unredeemable. They belong in Dante’s tenth and lowest circle of Inferno. The more assumptions introduced to explain it, the more confusing (perplexing) it becomes, and less satisfactory the results.

Reflecting on this, I came to think of evil as wickedness distributed across humanity in a pattern that resembled a Bell Curve. At the far-left end are the few “no goods,” the extraordinarily wicked: Bill. At the far right are the morally pure: the saints. Across the middle of the curve is the bulk of humanity, a mix of good and evil. This is where most of us toil throughout our lives. The “good” part of the mix is what makes those of us in the middle feel guilty about the wicked things we do. Folks on the far left of the curve are bereft of good; there is nothing in them to trigger guilt, nothing to make them feel bad about being bad. Like Bill, they can only fake it, can only pretend to feel guilty. Those on the far right of the curve suffer the most guilt because they cannot help but despise those all-too-human shortcomings that sully that moral perfection they yearn to possess, but is never quite in reach. Their exceptional goodness perhaps operates on themselves pathologically and ironically, as a burden. Their souls, like those of the supremely wicked, are unfathomable.

Wickedness, like intelligence, looks, athletic and musical ability, and sex appeal, is distributed unevenly among human beings with the plus-and-minus extremes at both ends of the curve. There are a few geniuses and their counterparts of dunces, a few saints, and the few occult monsters.

Stupidity cannot be fixed; neither can evil. Yet, while everyone concedes that stupidity is impossible to remediate, many think that evil is an accident or a breakdown that can be repaired by “experts.” The folly of Rousseau’s romanticism persists as a dogma of modern, progressive thinking: Even the worst of us, somehow, is fixable. Thus, the absurdity of the picture: the somewhat-wicked repairing the abjectly-wicked. We know in advance how it works out. Abject stupidity stands out as an embarrassment when displayed. Wickedness excels in the arts of concealment and dissimulation. Sometimes those who appear as saints are the beasts in reality.

Contrary to the utopian visions of Rousseau, Marx, and the progressive-liberals, evil is an indelible feature of the human condition. Philosophically and anthropologically, that conclusion points to the reality of human nature as inexorably flawed; the mitigation of evil, not its elimination, is what properly-ordered minds contemplate. Those with clear eyes understand that goodness competes at a disadvantage with evil, and often loses. There are too many temptations for wrong; too few incentives for right. It is not fair, but that’s the way the world works. In looking at the world as it is, there is a better chance of maximizing the probability that good people will prevail. Ideologies that idealize equality and promise human perfectibility, to paraphrase Marx, are “opiates of the masses.” When ideologues who pursue equality gain power, ruination follows.

This brings us, philosophically, to Edward Gibbon, Edmund Burke, Thomas Hobbes, and David Hume — each of whom attended to delineating the frailties and limitations built into human nature. Human conflict and quarreling remain constants. What holds them in check? Authority structures — family, government, church — maintained by customs, rules, norms, and laws that reward those who cooperate and punish those who defect. These structures are inherently hierarchical, conservative, historically grounded, and have been proven in the past.

The illusion of liberal-progressivism is that “progress” brings the flowering of each individualized personality unencumbered by the suffocating demands and restraints once imposed by hierarchical authority structures. The engine of progress delegitimates authority: No need for rulers with sovereign authority. Men will govern by benevolence and compassion; disputes will be settled by reasoned debate and consensus. Rule-governed processes will eliminate conflict; force gives way to reason. Hegel’s “World Historical Spirit” comes to mind. “The owl of Minerva begins its flight only at dusk”: the end of human history, a decisive conquest over mankind’s “darker angels.” The modern world of demolished hierarchies will feature the smart consumer, tolerant of everything but intolerance and embracing diversity, who carefully plans for a comfortable retirement while pursuing the enjoyments of the moment. This new, archetypical “global citizen” will, for the first time in recorded history, be able to utter a command translatable into a hundred languages, six words that make attainment of the good life complete for everyone, everywhere: “Put it on my Visa card!”

Until that happens sometime in the faraway future, to stay out of that Hobbesian “state of nature,” the “war of all against all,” someone has to decide what course of action will protect our property, our women, our tribe, and our lives. Someone must be in charge. Someone must decide: Who are our friends? Who are our enemies? Shades of Carl Schmitt.[11] [30]

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “Paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

- Third, Paywall members have the ability to edit their comments.

- Fourth, Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected] [31]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[32]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[32]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.

Notes

[1] [33] Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, “Leibniz on the Problem of Evil [4].”

[2] [34] Ibid.

[3] [35] Wikipedia [36]: “The Socinians believed that God’s omniscience [37] was limited to what was a necessary truth [38] in the future (what would definitely happen) and did not apply to what was a contingent truth [39] (what might happen). They believed that, if God knew every possible future, human free will [40] was impossible and as such rejected the “hard” view of omniscience.[10] [41] Modern process theology [42], and open theism [43], advance a similar viewpoint.”

[4] [44] Leibniz on the Problem of Evil.”

[5] [45] Tony Pitson, “The Miseries of Life [46],” in Hume Studies, vol. 34, no. 1 (April 2008).

[6] [47] Jean-Jacques Rousseau, “Discourse on the Origins and Foundations of Inequality Among Men,” in Political Writings, Alan Ritter, ed. (New York: W. W. Norton, 1988), 34.

[7] [48] J. L. Talmon, The Origins of Totalitarian Democracy (Boston: Beacon Pres, 1952).

[8] [49] Fatal Friendship: A Philosophical Novel, to be published late 2023 or 2024.

[9] [50] Jean-Jacques Rousseau, The Social Contract [51], at Marxists.org.

[10] [52] The jury members’ reaction to the details of the killing, according to some accounts of the trial, were emotionally devastating.

[11] [53] “The people which exists in the political sphere cannot, despite entreating declarations to the contrary, escape from making this fateful distinction [friend-enemy]. If a part of the population declares that it no longer recognizes enemies, then, depending on the circumstance, it joins their side and aids them.” Carl Schmitt, The Concept of the Political, expanded edition, George Schwab, tr. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), 51.