Whittaker Chambers: The Quaker Who Exposed Communism in the US, Part 1

Posted By Morris van de Camp On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled2,548 words

Part 1 of 2

The first significant anti-Communist victory in the Cold War’s early years did not involve any soldiers. In a century filled with warfare, the two principal contenders in this fight were men who were just too young to have served in the military during the First World War and yet too old to have served in the tragic and disastrous Second World War [2].

A literary work of great excellence that framed the fight against Communism in spiritual and moral absolutist terms was Whittaker Chambers’ Witness. One anti-Communist reporter, Robert Novak [3], read the book and said of it:

Early in 1952, as a twenty-two-year-old second lieutenant on active duty in the U.S. Army awaiting combat assignment (it never came) to a war in Korea that my government showed no desire to win, I read the newly published Witness. It changed my worldview, my philosophical perceptions, and, without exaggeration, my life. (p. xvii)

Witness was a tremendous influence on the American conservative movement during the Cold War. Passages from it were even included in Ronald Reagan’s famous 1983 “evil empire” speech [4]. Tom Clancy’s novel Red Rabbit [5] (2002) was likewise a techno-thriller which repackaged Chambers’ story in a dramatized form. Witness shows the ways in which Communism was both alluring as well as dangerous and destructive, but it reflected some flaws that also blinded the conservative movement, as will be discussed below.

The conflict at the center of Witness was between two men who were members of the American majority. Not only were they members of America’s founding stock, but they were also highly successful in their careers. The man on the anti-Communist side was the aforementioned Whittaker Chambers [6]. He was Senior Editor at Time magazine and was a well-regarded author, translator, and Maryland farmer. The other was Alger Hiss [7], an accomplished US State Department official.

Whittaker Chambers’ background

Chambers used many aliases — not just pen names, as he went by various names in his everyday life as well. This was related to his espionage activities, but it had been a practice of his since childhood. He was born Jay Vivian Chambers on April 1, 1901 to James A. Chambers and Laha Whittaker in Philadelphia. The Chambers family had been in Philadelphia for many generations. Chambers hated the name Vivian, however, and eventually settled on Whittaker.

Whittaker’s father was “Jay” Chambers. He came from an old Philadelphia family that had had Quaker forebears. One of his grandmothers on the Chambers side had sewn bandages for the Union army during the Civil War. His mother, Laha, was from Wisconsin. Her father, Charles Whittaker, had been a Scottish immigrant who had served in the Union army as a Corporal in Company C of the 5th New York Heavy Artillery [8] — a “convict regiment,” according to Charles’ account. During operations at Snicker’s Gap [9], another soldier jumped in front of Charles and was shot dead. Laha’s mother’s family had been Huguenots [10] who then became Protestant settlers in Ireland [11] before departing for the United States.

Whittaker’s grandfather, James Chambers [12], was a newspaper editor in Philadelphia and a loyal Republican voter. He was well-read on world affairs and argued that the Italo-Turkish War of 1911-1912 was destabilizing all of Europe. He was right; more war in the Balkans ensued, and the resulting instability led to the assassination in Sarajevo that sparked the First World War.

The Chambers family moved to Brooklyn, New York, where James worked as a graphical artist. At Laha’s insistence, the family moved again to Lynbrook on Long Island. Theirs was a humble house, but the forests and rivers of pre-suburbia Long Island were a landscape Chambers would come to love. But the Chambers family was not a happy one. Laha did what she could, but her husband Jay was bisexual and emotionally aloof. At one point, he even disappeared for a year to live as a bachelor in New York City. His Whittaker grandmother also developed mental illness in her later years, adding to the woes.

Whittaker Chambers married Esther Shemitz [13] in 1931, who had been involved in the pacifist movement, among other Leftist causes, and was an artist.

Alger Hiss’ background

After Franklin Delano Roosevelt took office in 1933, he brought many extremely talented people to Washington to administer the New Deal. Capitalism had crashed and burned on October 24, 1929 [14], and by 1933, the whole of the United States was feeling the economic pinch. One of those bureaucrats was Alger Hiss.

Hiss was a Marylander and a Quaker who came from a notable family in Baltimore. He didn’t grow up wealthy, but he was nevertheless of high social status and well-connected enough to get admitted to the Harvard Law School. After graduating and passing the bar, he served as a clerk for Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes [15] and future Justice Felix Frankfurter, a Jew.

Hiss worked as a lawyer in the Justice Department and was eventually transferred to a New Deal project called the Agricultural Adjustment Agency. There he met Harold “Hal” Ware, who was from an old south New Jersey family. Ware had worked for a group called the Friends of Soviet Russia, which was formed out of the Leftist and socialist labor movements that were common in the United States during the early twentieth century. Ware had gone to Russia after the Bolshevik Revolution to help collectivize the farms [17], becoming a committed Communist. Ware later organized a Communist spy ring that included both Hiss and Chambers.

Hiss married Priscilla Harriet Fansler, a woman from an Illinois Quaker family who had graduated from Bryn Mawr College. Priscilla was a killjoy; those who knew her said that ordinary remarks made in her presence would be met with a scolding response; even if someone merely remarked that it was a nice day, she would answer by saying that it was “not a nice day for poor sharecroppers” or something similar.

Hiss transferred to the US State Department in 1936, becoming an assistant to the Assistant Secretary of State. It appeared to be a natural move for an intelligent and ambitious man with many connections, but of course the real motivator was his Soviet connections. In retrospect, it is clear that this was part of a larger strategy. The plan was to move Soviet spies out of the US government’s alphabet-soup agencies and into cabinet-level jobs where they could influence American policy to the Soviet Union’s liking.

[18]

[18]You can buy Georges Sorel’s Reflections on Violence from Imperium Press here. [19]

By late 1944, Hiss was the Director of the Office of Special Political Affairs, the purpose which was to shape the post-war world. He was in fact with Roosevelt at the Yalta Conference in February 1945, but despite the fact that he was a Soviet spy, it is difficult to see anything that he did to help them there. The Yalta Conference didn’t hand Eastern Europe to the Soviets, as is sometimes asserted, but merely ratified their existing conquests.

During the conference that laid down the United Nations Charter in June 1945, Hiss was praised by the Soviets for his “impartiality and fairness.” Hiss probably helped them on that occasion, but it is not certain how. In fact, Hiss successfully maneuvered the Soviet Union out of receiving a UN vote for each one of the Soviet Socialist Republics comprising the Soviet Union. This convinced many Americans, and especially liberal Democrats, of Hiss’ innocence [20] when he was later accused of espionage.

The Ware Group & Communism’s cultural origins

Communist ideology grew out of the French Revolution’s violent form of Leftism, but it also owes a great deal to the ethnicities and life experiences of the men who created it: Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Marx was a German Jew who came from a family that had converted to Christianity. Engels was an ethnic German whose family were Pietists. Both men ended up in England when that country was the world leader in industry.

Of the two, Engels was far wealthier, and he supported Marx financially. It is possible that Engels was in fact Communism’s true creator. Engels’s family owned a factory in Manchester, as well as industrial properties in Germany. Both men examined the social problems arising from industrialization from a semi-religious standpoint, and Communism was their answer.

Marx and Engels held that political power had shifted from the aristocrats to the middle class in a natural way following the French Revolution. They therefore reasoned that political power would likewise shift from the middle class to the proletariat as the result of revolution. Society would then be remade into a utopia where the lion would lie down with the lamb.

[21]

[21]England’s northern Midlands are where many Quakers came from, and is also where England’s industrial revolution took place. The Quaker values of hard work, honesty, and fixed prices rather than bargaining played a large part in creating the manufacturing-based economy there.

Manchester is in England’s northern Midlands. Its coal-mining and factory-worker proletariat were in effect tribes unto themselves that were at odds with the owners of the mines and factories. The idea that the miners would one day take social power made a great deal of sense given that coal was driving the entire industrial economy, and no one suspected that it would one day be replaced. Communist ideology held that industrialization was part of humanity’s natural progress, and its early formulators never suspected that industrialization might end if the factors that underpinned it — profits, hard work, tariffs, and clear-eyed government policies — came to an end.

Western Germany, where both Marx and Engels had come from, as England’s northern Midlands, where Engels was to spend much time, are both tied by blood and commerce to the American Midlands.

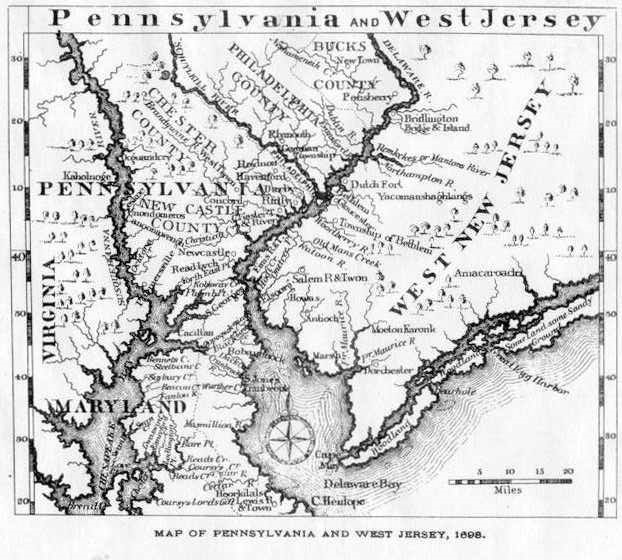

Two European ethnic groups converged in the Delaware River Valley: Anglo-Quaker settlers from England’s northern midlands as well as German Pietists and other Protestants from those regions of western Germany where Marx and Engels were born and raised. Out of this mixture, the culture of the American Midlands was born. This region encompasses northern Maryland, most of Pennsylvania, Delaware, and southern New Jersey, and its culture extends westward to the front range of the Rocky Mountains.

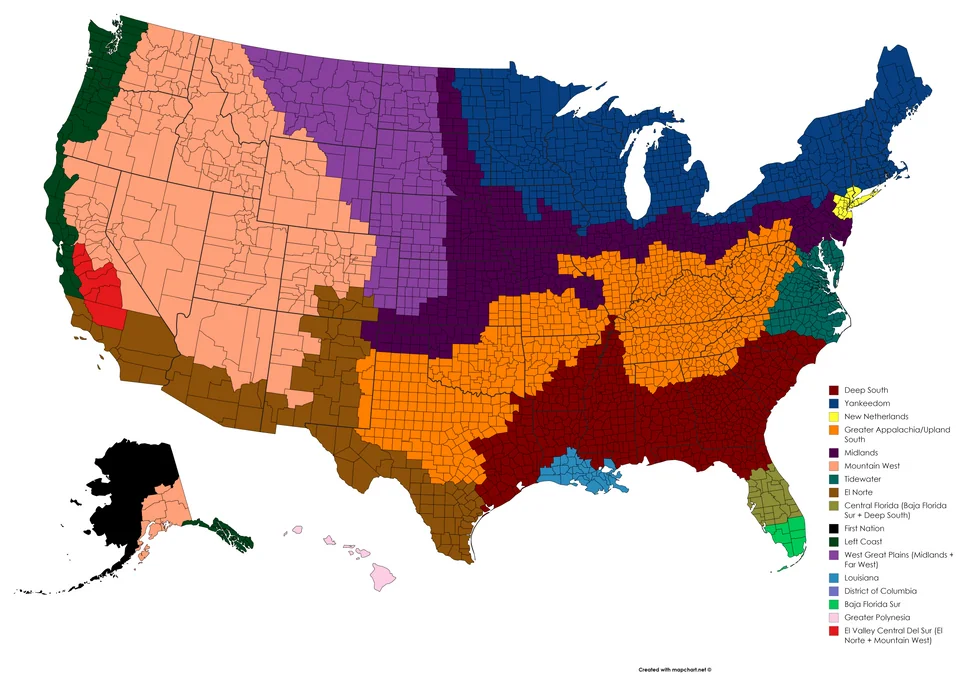

[23]

[23]This is a map based on Colin Woodard’s eleven nations of North America showing the American Midlands in two shades of purple. The American Midlands’ culture was established by Germans and Anglo-Welsh Quakers. Many of the Communists in the Ware Group were from the Midlands.

The Ware Group of spies was established by Harold Ware and “J. Peters,” whose actual name was Sándor Goldberger. Of the 16 men who were allegedly members of the Ware Group, seven were Jews or partial Jews. Six others were old-stock Americans with roots in the American Midlands, including Hiss, his brother Donald, Harold Ware himself, and Whittaker Chambers, among others.

The Ware Group’s activities

Chambers was helped in his spying by receiving documents from various US government officials, including Alger Hiss and Harry Dexter White, a Jew, who was working at the US Treasury. It has been claimed that White was the true architect of the Morgenthau Plan, which called for Germany’s deindustrialization following the Second World War.

Many of the documents Chambers got from Hiss had been typed on Hiss’ own typewriter. There were also notes transcribed on official US State Department stationary with the header torn off. These notes were transcriptions of secret US diplomatic telegrams and other classified information, including technical specifications, such as that of the Christie chassis. [24] Whittaker and his wife Esther [25] naturally became friends with Alger and his wife Priscilla [26].

Leaving Communism — first slowly, then suddenly

Chambers was first attracted to Communism in 1919. He’d run away from home during the final months of the First World War and had a job laying down trolley tracks in Washington, DC. He then moved to New Orleans, where he lived next to a bordello. He thus developed sympathies for the working class. He returned to Long Island and made friends with ordinary workers in taverns, becoming further drawn to Communism. When his brother died by suicide, he decided to become a Communist activist. His goal was to save the world. At first Chambers was an open, card-carrying Communist who edited two Communist newspapers, The New Masses and The Daily Worker, but the Communist Party of the United States eventually asked him to go underground in order to do work for Soviet intelligence. He married Esther Shemitz, a fellow Communist activist who was also a Jewess, in 1931.

Chambers first began to question Communism after several of his short stories for New Masses were condemned for being at variance with the party line in some way. But it was Stalin’s purges of his Communist rivals that motivated him to break with the movement, as even some American Communists known to him were targeted. In June of 1937, a friend of his, an American Midwestern woman named Juliet Stuart Poyntz [27], vanished in New York City after returning from a trip to Moscow. She had likewise begun to be disillusioned by the purges. Although she was never found, it was widely believed that she had been murdered by Soviet agents.

[28]

[28]Juliet Stuart Poyntz’s disappearance was one of the events that caused Whittaker Chambers to turn away from Communism.

Another factor in Chambers’ decision was the belief among the American Communists of the time that childbirth was unrevolutionary. Should a member’s wife become pregnant, she was expected to have an abortion. This ended up affecting Chambers personally:

One day, early in 1933, my wife told me that she believed she had conceived. No man can hear from his wife, especially for the first time, that she is carrying his child, without a physical jolt of joy and pride. I felt it. But so sunk were we in that life that it was only a passing joy, and was succeeded by a merely momentary sadness that we would not have the child. We discussed the matter, and my wife said that she must go at once for a physical check and arrange for the abortion. When my wife came back . . . she was quiet and noncommittal. The doctor had said that there was a child. My wife went about preparing supper. “What else did she say? I asked. “She said that I am in good physical shape to have a baby.” My wife went on silently working. Very slowly, the truth dawned on me. “Do you mean,” I asked, “that you want to have the child?” My wife came over to me, took my hands and burst into tears. “Dear heart,” she said in a pleading voice, “we couldn’t do that awful thing to a little baby, not to a little baby dear heart.” A wild joy swept me. Reason, the agony of my family, the Communist Party and its theories, the wars and revolutions of the 20th century, crumbled at the touch of the child. Both of us simply wanted a child. (pp. 273-4)

After his daughter [29] was born, Chambers marveled at her ear’s intricacies. He decided that such a structure must be the product of divine design, which invalidated Communism’s atheism. It was then that he vowed to break from the Communist underground and its Soviet god and return to his ancestral Quaker religion.

[30]

[30]Whittaker and Esther Chambers with their daughter. “Dear heart, we couldn’t do that awful thing to a little baby, not to a little baby dear heart.”

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “Paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

- Third, Paywall members have the ability to edit their comments.

- Fourth, Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected] [31]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[32]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[32]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.