The Truth About Irish Victimhood in American History

Posted By American Krogan On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled2,480 words

Protestants from the British Isles and Irish Catholics have long held animosity towards each other. I’m not going to discuss the Plantation of Ulster [2], but I assume most readers already know that anti-Irish discrimination was once a very real phenomenon. And it still is, if you consider that various groups are currently trying to replace the Irish people in their own homelands with Third World migrants. When this is discussed in public debate, however, the Irish people suddenly don’t actually exist in the establishment’s eyes. For them, Ireland is a “nation of immigrants” or some other such nonsense. The reality of the Irish people, such as that of other European ethnic groups, is never acknowledged — unless acknowledging their existence serves an ulterior motive.

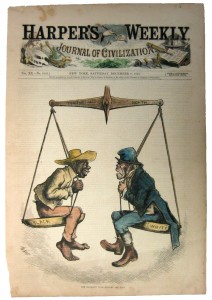

This is how Irish victimhood comes into play in the United States. It’s one of those narratives that definitely has truth to it, but has become increasingly absurd as time goes by, perhaps reaching its zenith with the idea that, once upon a time, the Anglo-Americans didn’t even consider the Irish to be white. Consider the example of “Colored & Irish washrooms” in Ken Levine’s 2013 video game BioShock Infinite [3], which is set in a fictional white Protestant ethnostate.[1] [4]

And yet, eight of the Declaration of Independence’s signers were Irish. Granted, most were Protestants of Scots-Irish or Ulster descent, but Charles Carroll was born to a family that came directly from Kings County in the Midlands, and was a practicing Roman Catholic. His surname derives from the Gaelic Ó Cearbhaill, and his ancestors were the rulers of the petty kingdom of Éile.[2] [5] Charles was a Maryland State senator from 1777 to 1800,[3] [6] and widely considered the richest and most well-educated man in America.[4] [7] That’s quite remarkable for someone who supposedly wasn’t considered white in a nation whose first act of Congress in 1790 was to reserve citizenship to “free White persons . . . of good character.”[5] [8]

Perhaps the most prominent icon of anti-Irish discrimination is the infamous No Irish Need Apply (NINA) signs that we are often told were once ubiquitous in the United States. I’m sure you’ve seen images of them online, usually in a context which implies that the Irish were treated like blacks. Even Ted Kennedy once claimed before the Senate in 1996 that he could “remember ‘Help Wanted’ signs in stores when I was growing up saying ‘No Irish Need Apply .’”[6] [9] Ted Kennedy, of course, like Charles Carroll, was a member of one the wealthiest families in America at the time.

There are two highly publicized papers available on the NINA phenomenon. One is by Richard Jensen, an American historian at the University of Illinois, who posits that it’s largely a victimization myth. His paper is entitled “’No Irish Need Apply’: A Myth of Victimization [10]” and was published in the Oxford Journal of Social History in 2002. Then there’s a rebuttal by Rebecca Fried [11]that was published in the same journal in 2015. Fried asserts that NINA signs were historically widespread. I found Jensen’s response to Fried’s rebuttal extremely compelling:.

The main theme of Rebecca Fried’s paper deals with newspaper help-wanted ads for adult men carrying the NINA restriction. Her appendix lists 69 citations from 22 cities, from 1842 to 1932. Over a third of her 69 citations are faulty — there’s no actual job being advertised. But let’s not quibble: let’s say that there were 69 newspaper stories from 22 cities over a 90 year period. Is that a lot or a little? . . . The Library of Congress in “Chronicling America” has a large collection of online newspapers, and offers an excellent search engine . . . It allowed me to search 9,458,697 pages of newspapers from every state from 1836 to 1922. The term “no Irish need apply” appeared on 230 pages. That is one NINA per 41,125 pages.[7] [12]

Some readers may note that Fried is an Ashkenazi surname of Yiddish origin.[8] [13] As it turns out, Rebecca Fried was only 14 at the time her paper was published. Her father, who is a lawyer, gave her Jensen’s original paper to read, and the historian Kerby Miller assisted her in writing it.[9] [14] When it was published in 2015, various media outlets ran headlines claiming that an eighth grader had “outwitted a college historian.” [15][10] [16] Now, I’m sure Rebecca was a gifted and talented girl at the time, since she was admitted to a very prominent private institution, the Sidwell Friends School, where Sasha Obama was one of her classmate [17]s[11] [18] — but even so, I find her story to be suspect.

Perhaps one motivation for Rebecca and her father to write the paper was to defend the work of the late Noel Ignatiev, a co-ethnic who not only shared Rebecca’s particular interest in the Irish-American experience, but also made it his life’s work to abolish the white race.[12] [19] I won’t go into great detail about Ignatiev’s book, How the Irish Became White, but it clearly had an agenda to use the Irish experience in America to undermine the legitimacy of white racial solidarity.

Literally no one — not even Richard Jensen — argues that anti-Irish sentiments never existed in American history. Anti-Irish sentiments were most prominent in America circa 1845, when the Irish were immigrating en masse during the potato famine. Anti-Irish sentiments were even more prominent in England. Curiously, Benjamin Disraeli, England’s first Jewish Prime Minister, made some exceedingly crass public statements about the Irish during this period:

[The Irish] hate our free and fertile isle. They hate our order, our civilisation, our enterprising industry, our sustained courage, our decorous liberty, our pure religion. This wild, reckless, indolent, uncertain and superstitious race have no sympathy with the English character. Their fair ideal of human felicity is an alternation of clannish broils and coarse idolatry. Their history describes an unbroken circle of bigotry and blood . . . My lords, shall the delegates of these tribes, under the direction of the Roman priesthood, ride roughshod over our country — over England — haughty and still imperial England?[13] [20]

Disraeli even had very public feuds with Catholic Irish men such as Daniel O’Connell, wherein he referred to the common Irish folks as “public beggars . . . swarming with . . . obtrusive boxes in the chapels,” and as a “starving race of fanatical slaves.”[14] [21] His comments may or may not have been representative of Jewish attitudes toward the Irish at the time, but it’s noteworthy that the second-most prominent person in anti-Irish politics in the Angloshere was Lewis Charles Levin, a Jewish man who lived in the United States during the same period.

[22]

[22]You can buy Greg Johnson’s New Right vs. Old Right here [23]

Lewis Levin was the first President of the Know Nothing party, which was the successor to the American Republican Party, of which he was also a member.[15] [24] Levin married two Christian women, and considering an assortment of details, it is plausible that he converted to Protestantism, though the evidence is perhaps circumstantial.[16] [25]

In addition to being known for his oratory talents, Levin was a notorious alcoholic who accrued large amounts of debt. He filed for bankruptcy in 1841 after exhausting the funds of his second wife’s late husband.[17] [26] (Curiously, he met his second wife while picking out the tombstone for his first.)[18] [27] Levin was also once charged with attempted murder, was shot in a duel, and even stabbed a fellow lawyer.[19] [28]

Although a lawyer by profession, in 1844 he was the editor of a local Philadelphia paper called The Daily Sun, which he used to spread his anti-Catholic message.[20] [29] But Levin wasn’t only a man of words. That summer he organized 3,000 Nativist Protestants to march into a Catholic neighborhood in Kensington, Philadelphia, starting a riot that ultimately left several people dead, many homeless, and three Catholic churches burned to the ground.[21] [30] Levin was later indicted for inciting the riot, but the case never went to trial.[22] [31] In fact, Levin went on to become a Congressman. He later campaigned for the Senate, which prior to the enacting of the 17th Amendment was a seat elected by the state legislature. He failed in his endeavors, however, and in 1855 he was accused of bribing government officials to win his Senate seat.[23] [32]

Needless to say, Levin was a very colorful and prominent character in the story of historical tensions between Irish immigrants and American nativists, yet Noel Ignatiev felt no need to discuss him at length in his book, How the Irish Became White. There is a brief reference to him in which Ignatiev states that Levin was arrested for “inciting to treason” in his newspaper,[24] [33] but that’s all. (Benjamin Disraeli, by the way, is a mere footnote in his bibliography.)[25] [34]

This is pure speculation, but perhaps Ignatiev didn’t wish to discuss Levin in greater detail because, as Zachary Schrag (who is also Jewish) states in one of his articles, Levin is a schande far di goyim.[26] [35] This Yiddish term isn’t quite as easy to translate as it may seem, since it can mean different things: a Jew who makes other Jews look bad to Gentiles, a Jew who brings shame to the Jewish people, or a Jew who in some manner betrays or undermines Jewish interests.[27] [36]

Zachary Schrag’s book on The Philadelphia Riots of 1844 is a very well-written scholarly work. It surprisingly gives great focus and prominence to Lewis Levin’s role in the Nativist movements of the time. But unsurprisingly, it still generally views nineteenth-century sectarian religious conflicts between Irish Catholics and Anglo-Protestants through a twenty-first century lens. To quote one such example:

The eruption of 1844 altered the landscape of both Philadelphia and the United States, but it may be even more important for the underground currents it revealed. Levin and the [Nativists] championed a vision of American citizenship limited to white, male, native-born, Protestant men. In the tumultuous 1840s, believers in this vision faced challenges from abolitionists, American Indians, early feminists, Mormons, and, not least, from Irish Catholic immigrants, who, even in these years before the Great Hunger, were already crossing the Atlantic by the tens of thousands. As these immigrants sought homes, jobs, votes, and the right to practice their faith, they presented an alternative vision of America, defined not by birthright but by a willingness to embrace shared values of freedom and democracy.[28] [37]

Schrag is anachronistically applying the pluralist vision that the 1964 Civil Rights Act and 1965 Hart-Celler Act imposed on America to a time when not even the “persecuted” Irish-Catholic immigrants believed in such pluralism. There’s plenty of evidence for this: In 1841, Irish immigrants rioted against blacks in Cincinnati, Ohio over labor and housing issues [38]. They did it again in 1866 in Memphis, Tennessee [39]. And in New York City in 1863, over a thousand Irish dock workers rioted over the Civil War draft, specifically targeting black workers [40].

The reality is that blacks eagerly participated in strikebreaking against Irish and other white workers in general. As one scholar put it:

The image of the black male strikebreaker in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was a powerful and broadly provocative one, arousing the concern, albeit in opposing ways, of white trade unionists and black elites alike. That image haunted organized white labor.[29] [41]

Any animosity the Irish held towards blacks was reciprocated. In Chicago, blacks actually referred to the Irish as “Green Niggers” and “flannel-mouths.”[30] [42] Of course, here is where certain folks push the idea that industrial capitalism invented ethnic and racial animus where there hadn’t been any before. But as Herbert Hill wrote in The Problem of Race in American Labor History:

Labor historians committed to the belief that racial conflict among workers is a consequence of class relations or an expression of “false consciousness,” celebrate the episodic occurrences of interracial solidarity while ignoring the overall historical pattern . . . For the working class to have been “divided” by external agencies it would need to have had an original unitary existence, but working-class identity does not exist before everything else; it is not primordial . . . While a multiplicity of factors besides race may have intersected at various times with class, race was decisive in the formation of the white working class during the period of slavery and again during its recomposition in the Reconstruction Period and after.[31] [43]

We cannot reinterpret nineteenth-century sectarian religious divides between white ethnic blocs and their subsequent resolution as being part of some path to modern notions of peaceful multi-racial pluralism, or as evidence that the white race is a poorly-defined ambiguous fiction. All the Irish-Catholic/Anglo-Protestant divide evinces is that there are no generic white people. Even within a racial grouping, there are smaller, but very meaningful, identities. None of this means, however, that we can simply ignore race. What we should take away from this is that mass immigration of any sort, even within a racial grouping of extremely similar peoples, can and will most likely cause tensions.

* * *

Like all journals of dissident ideas, Counter-Currents depends on the support of readers like you. Help us compete with the censors of the Left and the violent accelerationists of the Right with a donation today. (The easiest way to help is with an e-check donation. All you need is your checkbook.)

For other ways to donate, click here [44].

Notes

[1] [45] The Irish and Colored Bathrooms are located in one of Battleship Bay’s hallways. They are situated just before the entrance to the Arcade. The player encounters them after rescuing Elizabeth from Monument Tower and after leaving the beach area.

[2] [46] Ronald Hoffman, Princes of Ireland, Planters of Maryland: A Carroll saga, 1500-1782 (Chapel Hill & London: University of North Carolina Press, 2000), p. 1.

[3] [47] Charles Carroll of Carrollton Commemorative Medal [48], Marlyand Manual Online.

[4] [49] Jay P. Dolan, The American Catholic Experience: A History from Colonial Times to the Present (Garden City, N. Y.: Doubleday, 1985), p. 86.

[5] [50] Naturalization Act of 1790, 1 Stat. 103, enacted March 26, 1790.

[6] [51] Congressional Record Senate, September 9, 1996, p. S10054.

[7] [52] Rebecca A. Fried, “No Irish Need Deny: Evidence for the Historicity of NINA Restrictions in Advertisements and Signs.” Oxford Journal of Social History, July 4, 2015, p. 24. (Richard Jensen’s response is now included in Fried’s paper.)

[8] [53] “Fried Family History [54],” Ancestry.com.

[9] [55] Ben Collins, “The Teen Who Exposed a Professor’s Myth [56],” The Daily Beast.

[10] [57] Moriah Balingit, “Rebecca Fried: The 14-year-old student who outwitted a college historian [58],” Independent.

[11] [59] Hannah Orenstein, “This Savvy Eighth Grader Changed U.S. History With One Simple Google Search [17],” Seventeen Magazine

[12] [60] “Abolish The White Race [61],” Harvard Magazine.

[13] [62] Robert Blake, Disraeli (New York: Saint Martin’s Press, 1967), p. 131.

[14] [63] William Flavelle Monypenny, The Life of Benjamin Disraeli: Earl of Beaconsfield (London: J. Murray, 1910), vol. 1, p. 291.

[15] [64] Cyrus Adler & Frederick T. Haneman, “Levin, Lewis Charles,” in Jewish Encyclopedia (New York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1906), vol. 8, p. 41.

[16] [65] Zachary M. Schrag. The Fires of Philadelphia: Citizen-Soldiers, Nativists, and the 1844 Riots Over the Soul of a Nation (New York & London: Pegasus Books, 2021). Kindle edition, p. 12.

[17] [66] Ibid., p. 20.

[18] [67] Ibid., p. 13.

[19] [68] Ibid.

[20] [69] Adler & Haneman, “Levin, Lewis Charles.”

[21] [70] Schrag, The Fires of Philadelphia, Chapter 20.

[22] [71] Ibid., p. 302.

[23] [72] The Joint Committee of the Legislature of Pennsylvania in Relation to Alleged Improper Influences in the Election of United States Senator (Harrisburg, Pa.: A. Boyd Hamilton, 1855), p. 7.

[24] [73] Noel Ignatiev, How the Irish Became White, p. 163.

[25] [74] Ibid., p. 225.

[26] [75] Zachary M. Schrag, “Lewis Levin Wasn’t Nice [76],” Tablet Magazine.

[27] [77] “Gene Weingarten defines ‘Shanda for the Goyim,’ [78]” The Washington Post, May 17, 2011.

[28] [79] Schrag, The Fires of Philadelphia, pp. 8-9.

[29] [80] Eric Arnesen, “Specter of the Black Strikebreaker: Race, Employment, and Labor Activism in the Industrial Era,” in Labor History (2010), vol. 44, p. 320.

[30] [81] David Doyle, “The Irish and American Labour 1880-1920,” Saothar (1975), vol. 1, no. 1, p. 47.

[31] [82] Herbert Hill, “The Problem of Race in American Labor History,” Reviews in American History (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996), pp. 190, 193.