The Whale

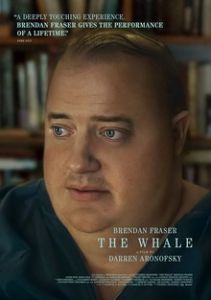

Posted By Steven Clark On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledIn Darren Aronofsky’s new film The Whale, Moby Dick gets referenced a lot, but its subject isn’t an actual whale. Charlie (Brendan Fraser), the protagonist, is rather a monstrous human leviathan whose massiveness can easily disgust others, much like the monstrously-deformed John Merrick, who was depicted in David Lynch’s 1980 film The Elephant Man. Merrick had to live masked and wrapped in canvas so as not to shock people.

Charles is wrapped up in his own canvas: He is an English teacher who conducts his classes online, purposefully blacking out his camera so that his happy, upbeat counseling voice is all that his students know of him.

If Jonah was swallowed by a whale and then became stuck in its stomach, Charlie’s house is a kind of stomach isolating him from the world as he self-destructs by gorging an endless feeding frenzy of snacks, subs, and two pizzas a day. I’m glad that all I ate before this film was a salad.

Liz (Hong Chau), his friend and nurse, rails at his 248 bp count, demanding Charlie go to the hospital, saying that he won’t last a week. Almost serenely, Charlie refuses as he wolfs down another meatball sub, which he almost chokes on. Liz saves the day, although there won’t be many more of them to save. She’s angry and aggressive where Charlie is serene.

Brendan Fraser’s Charlie is rightly considered to be one of his best performances, and his large, yearning eyes compel one to empathize and open his soul to Charlie’s presumed inner suffering inside all that revolting, slattern flesh. He’s homosexual and mourns his lover, who died sometime before. Charlie dumped his wife Mary (Samantha Morton) and eight-year-old daughter Ellie (Sadie Sink) to be with this man, whose room in his house is locked and kept pristine and spotless, unlike the rest of the dingy, grubby food-ridden house. This recalls Queen Victoria’s keeping the late Prince Albert’s clothes laid out on his bed every morning for years after his death.

Charlie keeps another memento mori; an essay about Moby Dick that he continually rereads, caught up in its description of the novel. The essay is neither bad nor good, but contains a sentence where the writer notes that Ahab has to destroy the whale to justify his existence, but the whale only does what it naturally does, and should have been accepted for that. The essay becomes a leitmotif , and it’s obvious Charlie is a whale, wanting acceptance for what he is, and what he has done.

The film is based on Samuel Hunter’s play, and retains a certain staginess that works for the most part, but also feels forced as the characters come and go, usually escorted by Liz, who becomes a kind of maid such as one finds in old plays who announce the guests. She is generally resentful and bitter about their comings and goings. The only entrance Liz wants is Charlie into the ER.

The staging recalls Milton’s Samson Agonistes, where a blinded Samson stands in front of the prison in Gaza before he makes his final stroke against the Philistines. He is visited by those who respect, chide, and mock him: Manoa, Dalila, Harapha. Father, mistress, and smirking giant.

Charlie is no Samson, but perhaps is blinded in some ways, and his visitors have their own problem with the vision thing. One visitor Liz thoroughly detests is Thomas (Ty Simpkins), a clean-cut young man whose essay Charlie likes. Thomas is an evangelical Christian and keeps visiting Charlie in the hope of getting him to convert to Jesus and save his soul before Charlie’s last supper, although for obviously different reasons. Thomas’s earnest proselytizing is met with predictable disdain by Charlie. Liz rages and kicks Thomas out into the rain.

While warily accepting Thomas, Charlie is excited about Ellie, who barges in after not having seen her father in eight years and sinks into a chair, moody, foul-mouthed, and obnoxious, and with all the compassion of a BLM or woke mob. She’s in trouble at school, and needs help writing an essay, but her toxicity makes anything resembling a hopeful visit impossible. Liz is ready to reach for a can of mace.

Charlie ignores the daggers in Ellie’s eyes as his own brighten in ecstasy. “You are amazing!” he exclaims to Ellie over and over. He only receives some arsenic-tipped verbal arrows from her in response. They had a nasty break-up, but Charlie’s protestations of innocence and his enduring love for Ellie are neither convincing to her or to me. True, those Brendan Fraser eyes sell his hopes; he’s like a manatee wanting a hug. But that phrase: “You are amazing!” Charlie being this exuberant at seeing his foul-mouthed daughter whom he abandoned years before seems forced and delusional. It reminds us that Charlie’s hopes and memories serve his own needs rather than the truth.

[2]

[2]You can buy Trevor Lynch’s Classics of Right-Wing Cinema here [3].

Ellie grows angrier and claws him with every scowl and word. He offers her the same advice he offers his students: Be honest. Forget the rules of writing or literary expression. Just be honest. He then quotes Walt Whitman. She shoots back that she thinks Whitman was an asshole. It’s true that he may be overrated, but Whitman’s “Song of Myself” is a paean to being free and unencumbered, and given that Whitman was also a homosexual, he provides justification for Charlie’s lifestyle as well.

Charlie’s problem is how to be the wise voice on the monitor for his students while also coming to terms with his past and his dead lover, all while trying to get Ellie to accept him. It turns out that the essay he keeps rereading was written by Ellie before their breakup. He still loves that Ellie,and wants her — and everyone else — to accept him as the whale. He can’t help what he does, in his eyes; he’s just what he is. Captain Ahab, go away. But who is Ahab in this scenario?

The Whale is a very dark movie, balanced only by Charlie’s decency. I paid less attention to Aronofsky’s direction than to the script. Aronofsky’s theme is that of troubled people, just as in The Wrestler and Black Swan: people overcoming inner angst or physical torment that is destroying them as they seek to fulfill themselves, which they must try to do in a race with their own demons, both past and internal.

Samuel Hunter’s script emphasizes the trials of being homosexual, and also shows how a religion can hurt outsiders through the church that Thomas had once been a part of but then broke with because they wouldn’t proselytize. A review by Randall King in the Winnipeg Free Press sums up the anti-religious angle, noting that the film is set in 2016: “When American evangelicals are on the verge of unleashing their own political plague on the world: a license to hate the others.” Really, is that what’s happened? So BLM, the woke mobs, the federal government arresting and jailing dissidents, and social media censorship doesn’t exist? No, it’s all those Evangelicals marching on Washington and persecuting homosexuals who are the threat.

The background noise from the TV can be heard throughout Charlie’s house; we hear discussion of the chances for Trump’s electoral success. Charlie symbolizes America. It, too, is gluttonous, weak, and unable to deal with its problems because it is caught up in its past and unable to move forward. That wonderful sixties world of free love and gay rights is now, through Charlie, a deformed freak destroying itself. His gross obesity is a symbol of our own as a nation.

When Charlie attacks a pizza, devouring slice after slice in unrelieved passion (the only truly passionate moment in the film), I see America. Needless to say, the daily consuming of two pizzas a day made me think of Pizzagate. Was this intentional? Mocked a couple of years ago as a conspiracy theory of the Evangelicals?

Charlie has a meltdown at the end, urging his students to dispense with any kind of serious critical analysis or following of literary rules. He finally switches on his camera, and his students are shocked at the whale who has been guiding them.

It’s an unmasking that shows how people are still offended at obesity, despite efforts by the establishment to “normalize” it. We see spandex ads featuring 300-pound black women to show the beauty of it. But it isn’t.

Charlie’s final reveal recalls the opening scene Dead Poets Society where Robin Williams, playing an oddball English teacher, joyfully urges his students to rip out the introduction on understanding poetry their textbook because it’s nonsense. Kids have to feel, not think. This they do, and Robin sells them his carefree anarchy, much as Brendan Fraser sells his deformity and moral failing.

The Whale is a film that can be seen as being about the suffering of a homosexual who lost his lover, but the implications of his life amidst a very sad and sick world dominate. Had Brendan Fraser played the role in his actual size, the film would have been ignored or seen as hopelessly dated. But Charlie represents an America that is corrupt and putrid. We’re fat — not as much as Charlie, but we’re getting there. It becomes saccharine about its wonderful past as it gobbles, scarfs, and devours in the present, eating away decades of prosperity with no regard for tomorrow.

Dimitri Orlov said the United States is committing suicide by denying reality. Karl Rove would probably reply by saying ,“We’re an empire and create our own reality.” “Our” reality is, like Charlie’s, diseased, and we are at war with our own soul.

I don’t dislike The Whale. On the contrary, I found it moving and it made me think, which is always a pleasure. While not admirable to me, Charlie is a empathetic and strong character — but strong in what sense? Similarly, where is America’s strength today? It’s fossilized, waiting for a release from its addictions while fighting it with all the determination of an addict who resists when being offered the truth and a path to recovery.

At The Whale’s conclusion there is an apotheosis of sorts when Charlie, presumably ready to die, painfully forces himself to abandon his walker and cane and then clumps towards Ellie. Is Charlie, like America, going to survive an avalanche of gluttony and self-loathing? The movie ends with no real answer. What about ours?

* * *

Like all journals of dissident ideas, Counter-Currents depends on the support of readers like you. Help us compete with the censors of the Left and the violent accelerationists of the Right with a donation today. (The easiest way to help is with an e-check donation. All you need is your checkbook.)

For other ways to donate, click here [4].