The French Emperor, the German Nutcracker, & the Russian Ballet Part 1

Posted By Kathryn S. On In North American New Right [1]

[1]Left: Antoine-Jean Gros, Premier Consul Bonaparte, ca. 1802; Right: Cover for E. T. A. Hoffmann and Alexandre Dumas’ The Nutcracker & the Mouse King

5,234 words

Part 1 of 2 (Part 2 here [2])

Like many of us this past season, I have had to endure far too many repetitions of the same 11 ”holiday” songs that fail to capture the essence of the season: the contemplative, dirge-y, or haunted side of winter, paired with the tasteful emotional warmth and childlike joy of Christmas. One of the reasons why Pyotr Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker ballet appeals to me is that its aesthetics, plot, and music successfully blend into one composition candy-lands and sugar plums along with these darker qualities — the dual child and mortality-centricity that makes fairy/folk tales so timelessly compelling. The other reason is that my mother was a ballerina herself for many years, and her favorite role was the Nutcracker’s Sugar Plum Fairy; we never passed a Christmas or New Year’s without watching at least one performance of that ballet. This has resulted in a perhaps excessive addiction to collecting nutcrackers, but I regret none of it.

Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker (1892) took as its source material German writer E. T. A. Hoffmann’s “Nutcracker and the Mouse King” (1816) and Alexandre Dumas’ close French retelling of the same (1844). In the novellas, the young female protagonist was named “Maria,” or “Marie,” rather than the ballet’s usual “Clara,” but in essentials these interpretations were quite similar. For the purposes of simplicity, this essay will use a composite of all three versions, leaning most heavily on Hoffmann’s.[1] [3]

Like elements common to these three interpretations included a Christmas Eve party in early nineteenth-century Germany. Marie and her brother Fritz/Franz received gifts from their enigmatic, mechanical whiz of a godfather, Herr Drosselmaier. Fritz got toy soldiers and a wooden horse to indulge his cuirassier fantasies. Marie, on the other hand, got a “funny little man,” also carved from wood: the Nutcracker, of course, with whom she immediately fell in love.[2] [4] As is the wont of brothers everywhere, Fritz antagonized his sister and broke her new toy. Godfather Drosselmaier consoled her by piecing the Nutcracker together again. The party ended, and the children went to bed.

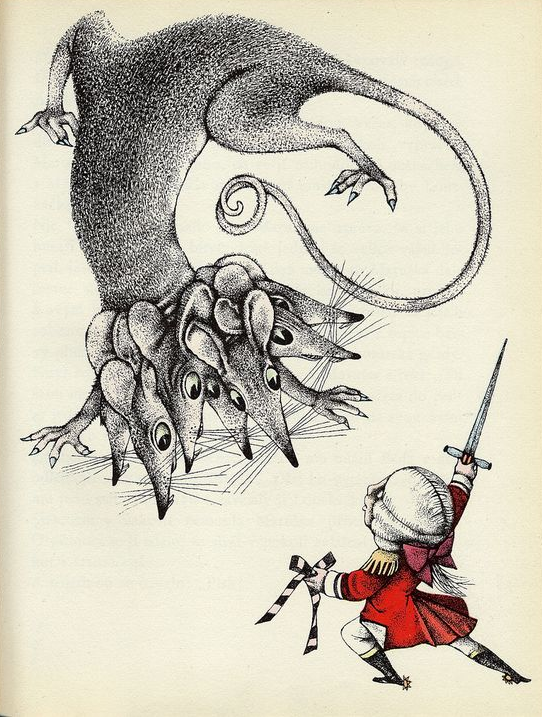

At nearly midnight, Marie awakened and went to check on her Nutcracker; but as the old clock in the hall knelled the arrival of the witching hour, marvelous and terrible things began to happen. The Christmas tree grew to impossible and wild proportions, while from all corners of the room multitudes of rodents emerged, led by an evil, seven-headed Mouse King. At this desperate moment Marie’s Nutcracker came alive, mustering Fritz’s toy soldiers to battle the wicked mice and save Marie from the Mouse King’s clutches. After defeating his enemies, Nutcracker transformed into a prince, whisking her away to winter wonderlands and fairy realms. But as dreams must do, Marie’s ended all too soon. With a start she awakened in her bed, almost as if these romantic adventures had been nothing but sugar plums dancing in her head.

Nutcracker belongs to that delightful genre of “portal fiction” in which the characters travel to far away and extraordinary kingdoms via ordinary objects/passages close at hand; so distant and yet so near — just beyond the looking glass, the wardrobe, the cupboard, the rabbit hole, or the enchanted river up the road. I could simply write about that, but the discriminating readers at Counter-Currents deserve a real (post-)Christmas effort. As Hoffmann published Nutcracker in 1816, mere months after the final angry blast of the Napoleonic Wars; as Dumas was obviously steeped in the Napoleonic sensibility (his own father was a general in that conflict); as Tchaikovsky inherited the Russian preoccupation with the “Patriotic War” of 1812, it should come as no surprise that Nutcracker had Napoleonic correlates, some subtle and others overt.

[5]

[5]You can buy Jonathan Bowden’s Western Civilization Bites Back here [6].

I’ve discussed ballet and war before in a piece [7] about The Sleeping Beauty and The Rite of Spring. Even though it might seem counter-intuitive, ballet — that celestial, civilized, twinkle-toed dance — might be one of the art forms most connected to battle and its brutalities. Both are theatrical performances in which duels and duets become parallel, if not one, phenomenon. They require the young and vigorous to sacrifice their bodies, while “moves” and formations are precisely timed choreographies of physical action. Ballet can even become a tool for diplomacy, or propaganda purposes. Many nineteenth-century ballets included gratuitous multi-nationalism that did not necessarily undermine nation-states, but served to reinscribe and celebrate national differences. I suspect that ballet des nations of this kind continued an old European penchant for collecting and role-playing in “sets”; another way to express the Western Classical and medieval desire to order and organize the world; the staging of games whose individual figures represented the different collectives: the planets, virtues, sins, exotic races, castes, archetypes, the Classical gods, the constellations and continents, and so on. They also indulged a taste for the exotic — something to which the stage (and the battlefield) has often been drawn.

So, children gather ‘round, and I will consider the fairy story alongside one of the most infamous winter adventures in all of Western history: Napoleon’s march into and retreat from Russia, a human disaster involving great numbers of these three European peoples mentioned earlier (French, German, Russian) who drove each other near to their death rattles. If there was any event that illustrated winter as something more than pretty images of “a winter wonderland,” “yuletide by the fireside,” “candy canes and silver lanes aglow,” and “sleigh bells in the air,” it was the Campaign of 1812. Nutcracker and Napoleon’s Russian invasion were both dreams of a white Christmas, the one by little Marie and the other by youthful Mari-anne.[3] [8] These visions were both dark and lovely, sumptuously red and blindingly white. Their champions were prince-soldiers, who seemed to have emerged from the woodwork (so to speak) – odd little men[4] [9] who could crack any nut or fearful challenge. Indeed, so entranced by these warriors were Marie/Marianne that they followed them down dark paths and into far-flung realms. The male heroes made a conquest of hearts, and vassals swore friendship and offered them gifts, entertainments, and feasts. For a brief moment, and just like their fictional counterparts, Marianne and her Corsican wunderkind seemed to have escaped the mortal world to find transcendence. How unfortunate it is that genius, by its nature, seeks its limit, and in this it always succeeds; that imperialists must continually push and extend their dominion till they dissolve, or collapse all that they built. How easy it is to forget that winter is that first of fathers, that most implacable of empires, that oldest of killers.

I. “To the Fight!”

In the spirit of darkness and childhood wonder that all successful Christmas stories must interweave, Hoffmann’s Nutcracker began during “the deep evening dusk” of Christmas Eve. To Marie and Fritz, everything “felt quite eerie because, as was usual on this day, no light had been brought in . . . [and], thoroughly pressed together, [they] did not dare say . . . [a] word.” Outside it sounded as if “rustling wings encircled them,” as well as “a very distant and very splendid music. A bright shine grazed the wall, and now the children knew that the Christ Child had flown away on radiant clouds, flown to other happy children.”[5] [10] They knew also that their parents were preparing gifts for them and for the Christmas party they hosted every year. Finally, they were beckoned into the drawing room, where wonderful presents awaited them.

As the revelry began in earnest, Marie spotted beneath the Christmas tree an “excellent little man” who stood, “quiet and modest,” calmly awaiting his turn. Though made by Godfather Drosselmaier, the elderly eccentric laughed at her infatuation. How could such a lovely little girl fall in love with that “thoroughly hideous manikin?”[6] [11] As we all know, readers, the heart often sees with other eyes what the eyes of others cannot fathom.

At that time, Marie was in need of a hero, for an even more grotesque seven-headed Mouse King had visited her several times in the night, “his eyes scintillating with a gory flame, and his seven mouths open as if he were about to devour poor Marie.” During each of these terrifying visits, he demanded sacrifices: “I thumb my nose! I thumb my nose! . . . I won’t be caught! I thumb my nose! But you have to give me your picture books and your petite silk gown. Otherwise, watch out!” On this particular night, and at nearly 12 o’clock, Marie hurried to the glass cabinet case where her beloved Nutcracker stood, injured but unbowed. A sudden and soft “whispering and murmuring [rustled] all around, behind the oven, behind the chairs, behind the cabinets.” Whistles of “wild giggling” mounted, mounted in volume, until “a thousand little feet were trotting and scurrying behind the walls and virtually a thousand little candle stubs were flickering through the cracks in the floorboards.” Candle stubs? No! These were “tiny, sparkling eyes,” much like those of the dreadful Mouse King. Marie realized that mice were “peering out and preparing themselves everywhere.” From floor to ceiling, the room reverberated with “brighter and denser squads of mice [who] were galloping to and fro and they finally lined up in rank and file, the way Fritz stationed his soldiers before a battle.”[7] [12]

Worse, beneath her bare feet, “as if driven by subterranean force, the ground spurted out sand and lime and crumbling wall stones,” and the Mouse King rose from what could only be the depths of Hell. This awful leader squeaked loudly three times, while facing his army. Then, “Hott, hott, trott, trott, it headed straight toward the cabinet, ah, straight toward Marie, who was standing right up against the glass” pane. Beset on all sides, the little girl swooned and crashed into the door, shattering the glass and gashing her arm. But lo! All was not lost, for the crash and the spilling of Marie’s blood set free the martial toys from the cabinet, including her Nutcracker. One of Fritz’s drummers rolled the battle summons, and in a rousing call strikingly similar to La Marseillaise, the Nutcracker cried, “Wake up, wake up, to the battle this very night! Wake up, wake up to battle!” Drawing his sword and with natural charisma, he asked, “You, my dear friends and vassals and brothers, do you wish to help me in the hard struggle?” In answer, “the soldiers leaped out and down in the bottom shelf, where they collected in glossy teams.” Regiment upon regiment of cuirassiers, dragoons, gingerbread men, dolls, and porcelain Chinese emperors paraded before him “with flying colors and fife and drum . . . across the floor of the room.” Fritz’s cannoneers then rolled up, and soon the guns “went boom — boom, and Marie saw the sugar peas smash into the thick pile of mice.”[8] [13] A Grande Armée, indeed.

At this, the Mouse King and mice “squealed and shrieked, and they again heard Nutcracker’s tremendous voice issuing useful orders,[9] [14] and they watched [him] as he marched over the battalions standing in the line of fire.” The Harlequin doll, all floppy arms and long, loping strides, “launched a few brilliant cavalry attacks and covered himself with glory.” But Fritz’s Hussars were “pelted by the mouse artillery with ugly, smelly bullets, which left nasty stains on their red jerkins [mouse turds? Oh, dear!].” The Chinese emperors, meanwhile, executed en carré plaine[10] [15] before getting their faces chewed off; the poor gingerbread men suffered the same fate. With desperation, the Nutcracker shouted hoarsely for his last reserve: “send the Old Guard forward, where are you?” — an obvious Napoleonic allusion, if ever there was one.[11] [16]

Having regained her wits, Marie launched a shoe at the Mouse King, just as the old devil attacked her Nutcracker. With a mighty thrust of his sword, Nutcracker stabbed his enemy, and his rodent minions melted away into the floorboards once more. “The treacherous Mouse King was defeated and now “rolling in his own blood.”[12] [17] Once again, bloodshed authored a magical transformation, for with the victory Nutcracker became a dashing prince, who now took possession of his foe’s seven crowns and Marie’s hand. To the wardrobe they dreamily went, and the Nutcracker Prince pulled a tassel hanging down. They both disappeared up a shirt sleeve and into an enchanted dimension. The Great Lemonade River lay before them, and beyond that the Christmas Woods. This, Marie was certain, would be the best, most magical white Christmas of her young life.

The worst white Christmas in Western history actually began during the high-tide of the sweltering summer of 1812. Well, in truth it began long before that. France had suffered a calamitous eighteenth century: humiliating defeat in the Seven Years’ War; wolves terrorizing the peasantry [19]; bloodthirsty Revolutionaries terrorizing everyone else; the Sun King had set and left lackluster successors behind, unequal to their tasks; hideous slave revolts,[13] [20] paired with the loss of her most lucrative sugar colonies; regicide; and now, half of Europe had managed to put aside their litany of grievances to form a coalition for the express purpose of invading and subjugating her. If Marie’s encirclement by rat-mice was literally her darkest hour (midnight), then events pressing upon poor Marianne were her metaphorically darkest and most desperate of them. There she lay, trembling and bleeding before her enemies all arrayed.

But who should come to her rescue, but a “funny little man” with a funny name and a funny accent! Surely no artillery officer — by universal consensus the least glamorous (but most intelligent) branch of the military — could possibly save the day. Indeed, wielding a winning combination of genius, luck, and a “whiff of grapeshot,” Napoleon Bonaparte scattered all her enemies before him. If ever there was a “Faustian Man,” it was Napoleon. And like all Faustian men, he sought not only greatness, but escape from limitation and death — for immortal glory. Here was a conquering hero, an Emperor who divested his foes of at least seven crowns and many lesser diadems, each liege-lord compelled to lay his sword at the General’s feet. Alas, such rapid success does not bring satisfaction, but hubris.

On June 23-25, 1812, Napoleon and a host of 600,000 troops — to that point, the largest force ever assembled — crossed the Nieman River.[14] [21] It was a portal over which they would enter a strange realm most had only heard about in stories: Russia, land of semi-divine despots and “savage” Cossacks. Victory would lead to even greater and more exotic places in Asia — cities that had been beyond even the reach of Alexander the Great’s whirlwind tour of conquests. Numbering among Napoleon’s ranks were his own French subjects, along with Dutch, Italian, Spanish, Austrian, Prussian, and Polish allied troops. On this company of multitudes, the Sun shone “radiant and lightened with his fire a magnificent scene.”[15] [22] The right bank glittered with the flash of helms and bayonets. During no other era had the military uniform resembled so much a costume for the stage: the braided cords, shakos, tasseled epaulets, bearskin helms, and hussar jackets didn’t match, but it didn’t matter. With unparalleled martial beauty, this ballet des nations struck up their marching bands, crossed the river, and entered the Romanov Empire.[16] [23]

There was romance, yes, but the French Emperor had practical reasons for invading Russia, and they were all about power — a subject he understood better than most. He would suffer no rival for European dominion, and (the rather callow) Tsar Alexander I fancied himself just such an opponent. It was insulting. Napoleon was also conscious that he “in no way resembled those kings by divine right, who [could] consider their states as their inheritance.” People like that may profit by tradition, but he could not. France was “hated [both] by [her] neighbours” and various “malcontents at home.” When staring down so many implacable enemies, a state “[stood] in need of brilliant deeds and consequently of war.” France must be “the foremost of [nations] or [she] must perish,” he reasoned. Both Napoleon and Alexander represented his counterpart as a monster, and himself as a savior — not only of his respective nation, but of Western civilization. The Tsar was an “enemy of Europe,” and Napoleon meant to “put an end to the fatal influence which Russia [had] exercised over [her] for the past fifty years.”[17] [24] For his part, Alexander became convinced that it was his special destiny to save all of Christendom and its Divine Right of kings from the Corsican Ogre, or as the Tsar preferred to call him: “the Antichrist.”

[25]

[25]You can buy Kerry Bolton’s More Artists of the Right here. [26]

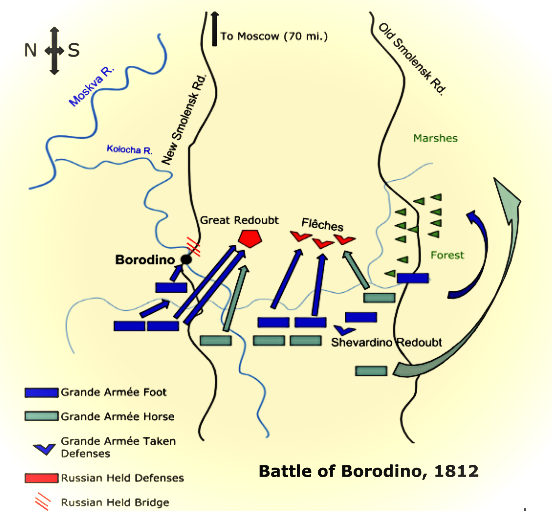

By September, Napoleon and his Grande Armée had ventured (too) deep into enemy territory, but they had finally forced the Russians to give battle. His army pitched camp between two roads, 70 miles from Moscow, and near the little town of Borodino. On the evening of September 6, he planned his formations and movements, before “the silence and darkness of midnight stole upon” his army; while the fires of the sleeping soldiers, almost extinct,” shed their “last rays of light over the heaps of arms piled around.”[18] [27] The air was oppressive with anticipation. Like children during the darkest days of December, they “huddled together in [clumps]. . . gloomy and fearful,” for they “fancied that death [hovered] above” their heads. Just before daybreak, the “roll of the drum” began to beat out the pas de charge, and officers cried, “To arms!”[19] [28] The battle that followed would be as surreal and nightmarish to soldiers as the fight between seven-headed, man-eating mice and tin men would be to a little girl. But surely — yes, surely — their hero-emperor wielded his magical mastery yet; still shone with the “Sun of Austerlitz”; still must this man have enjoyed his divine right with their war gods, if not with foreign kings.

First light revealed the Emperor’s army drawn up in “unprecedented size and splendor.” Everyone, from marshals to privates, were commanded to look their best. A Polish captain glanced behind his shoulder towards the captured Shevardino Redoubt and saw “the Old Guard standing [there] in their parade uniforms, with their red plumes and epaulettes showing across the fields like a stripe of blood.”[20] [29] Unlike Napoleon’s previous engagements, this day’s fighting tactics would be simple and brutal. The Grande Armée would march straight into the bared teeth of Russian resistance and drive their foes out of their primary entrenchments: from the town itself, from the triple-notched Bagration Flêches, and from the infamous Great/Raevsky Redoubt. The latter two were manned with incredible cannonade and courageous defenders, all of whom were determined to die where they stood. Witness accounts of the battle agreed that “lines were opposed to lines, man to man, and the appeal was made to each individual soldier’s courage.” The day “depended upon the exertion of power rather than the delicacy of manoeuvre or the caprices of fortune.” The personal examples “of the chiefs, the charge, the storm, the repulse and the stand were the only tactics; the cross fire of cannon the only operation of strategy.”[21] [30] Over 250,000 men faced one another along a short three-mile front; as many as 600 pieces of Russian artillery concentrated their fire into these tightly-packed, advancing columns – sometimes at point-blank range. A similar number of French guns bombarded Russian earthworks without pause. The resulting slaughter shocked even the most callous among them.

Films do a generally poor job of depicting the effects of the artillery “experience” (and perhaps that’s just as well). Cannonballs, for instance, did not hit the dirt, then quit their motion; they ricocheted and rolled with incredible kinetic energy for some distance, depending on the landscape and weather. Even the wind created by the rushing wake of one of these missiles could cause severe bruising if someone was close enough to its passage as it barreled through the air.[22] [32] When a solid shot landed, then bounced and rolled along the ground, veterans had to caution greener comrades not to try and stop them. Even if round-shot appeared to be moving slowly enough to arrest, it could still take off feet and legs. Marching under fire became a deadly game of hop-scotch, as soldiers jumped and skipped their way over and around these smoking iron bowling balls.

Likewise, neither canister nor grapeshot caused men to pitch forward into clumsy half-cartwheels (see the film Gettysburg for examples of this mistaken imagery); they simply mowed down their victims with appalling force and inflicted ghastly injuries capable of rendering the human body indistinguishable from raw meat on a butcher’s slab. Shells detonated and broke apart into shards of anti-personnel shrapnel with obvious consequences for anyone near the explosion. If especially skilled, artillery engineers could calculate and cut wick-lengths set to go off directly over the heads of enemy troops, raining death and demoralization from above. Indeed, artillery’s most powerful effect was a psychological one. It required tremendous amounts of fortitude to continue standing or marching in formation amid the constant din; amid the screams of the wounded cut down mere feet from one’s own position. The attitude of men advancing into such a barrage was natural and universal: face and body turned, eyes squinted, shoulder leading and braced as though they faced a windy rainstorm, rather than fire and iron. A Russian defender described the oncoming “thick masses” of men, their roundshot ploughing “wide and deep holes [in French lines] . . . Entire platoons fell simultaneously.” Suffocating clouds of powder smoke “curled from the batteries into the sky and darkened the sun, which seemed to veil itself in a blood-red shroud.”[23] [33] Visibility plummeted. Can anyone doubt that the inability to see in the midst of danger is one of man’s most visceral and instinctual triggers?

[34]

[34]You can buy Tito Perdue’s Though We Be Dead Yet Our Day Will Come here [35].

Yet, time and again the French threw themselves at the Great Redoubt, the area around it resembling “a stormy sea.” Constant movement of back-and-forth feet “pulverized” the earth. With every canister ball “flogging up a little cloud of dust the whole area crawled like moving waves.” The French infantry, in uniforms the color of storm clouds, was “a mass of moving iron: the glitter of arms . . . reflected from the helmets and cuirasses of the dragoons,” then mingled with the “flames of the cannon that on every side vomited forth death.” The combined effect gave the “appearance of an [erupting] volcano in the midst of the army . . . a dreadful yet sublime picture.” On the one side, French forces fought with a wild joy borne of “the highest degree of despair.”[24] [36] Trapped deep inside Russian territory, they knew the day could only end for them in victory or death. On the other side, Russian defenders fought with the fanaticism of a people determined to avenge the despoiling of their sacred soil, of Holy Mother Russia. There would be few prisoners.

In a final, late-afternoon assault, the French clawed and scrambled once more up and into the Great Redoubt. The Russian cannon heaved a final salvo — then fell silent. From a distance, a Russian jaeger described a “dull cheering [that] told [him] that the enemy had burst over the rampart and were going to work with the bayonet.” While he was left to imagine the carnage inside the barricade, one Pole saw with his own eyes the dreadful prospect. Amid the butchery he almost tripped on the body of a decorated Russian cannoneer. In one fist the fallen man “held a broken sword, and with the other he firmly grasped the carriage of the gun at which he had so valiantly fought.” There were few words

to describe the impression made by the sight of the Raevsky Redoubt . . . dead and mutilated men and horses [lay] six or eight deep. Their bodies covered the whole area of the entrances. They filled the ditch and were heaped up inside the fortification.[25] [37]

Aside from the slaughter, the most striking thing about Borodino was the French Emperor’s conduct. Napoleon had been an energetic commander in previous campaigns, often riding “up and down his lines of battle, greeting scarred veterans whom he recognized” from past ventures. At times he halted dramatically in front of a battered regiment, and “there he would find out if any officers’ places had fallen vacant, then ask in a loud voice the names of the men most worthy to fill them.” He summoned the fellows who were pointed out to him, and next proceeded to interrogate them: How many years of service did they have? What campaigns had they been through? What wounds had they suffered? Had they performed any brilliant deeds? After this questioning, “he promoted them officers and had them commissioned there and then in his presence.”[26] [38] It was a piece of stagecraft that depended on an energetic charisma, the personalism of which mesmerized the common soldier and bound the Emperor’s subordinates to him directly. Indeed, all “were accustomed under such circumstances to see him managing affairs with a confident and tranquil air . . .”[27] [39]

But at Borodino, none of this more youthful energy was in evidence. Instead, Napoleon’s marshals “saw [naught] but feebleness, lethargy, and inertia” from their Emperor. Those who attended him “regarded him with astonishment.” Behind their hands and with faces averted, “some ascribed his want of energy to fatigue; others thought that he was tired of everything, even of fighting, while [a few] suspected internal sufferings.” To one staff officer’s consternation, he remembered having left Napoleon’s side in the morning, only to come back several hours later to find “the Emperor still at the same spot, evidently in pain, and in a state of despondency; his features were downcast, his eyes dull and heavy, and he gave his orders in a listless way . . . Every one was surprised.” In truth, Napoleon was very ill. A particularly bad flu combined with an acute bladder condition, the stabbing pains of which prevented him from mounting a horse, or doing much at all besides sitting on a chair and watching the ensuing bloodbath through a spyglass. Worse, when the moment to use his reserve troops to deal the crushing blow seemed to arrive, Napoleon balked. General Daru, “instigated by [generals] Dumas and Berthier, [whispered] to the Emperor that the universal cry was, ‘Now is the time for the Guards to attack!’” But Napoleon vacillated, then answered in the negative: “And if I have to fight a second battle tomorrow, what troops shall I have to fight it with?”[28] [40] Whether this decision was a missed opportunity to deal the Russian army a fatal blow, or if it was wisdom coming from a commander who knew how far he was from friendly territory, its delivery showed a lassitude that was new and alarming. Never before had the Emperor appeared so indecisive at such a crucial moment.

If the chivalry in Nutcracker was ironic for its deliberate, comically overacted melodrama (“Oh, demoiselle! . . . [the Nutcracker] tore off the ribbon Marie had bound about his shoulders, pressed it to his lips, hung it across him like a scarf, then boldly leaped” into the fray),[29] [41] then the chivalry at Borodino was ironic for its indeliberate, but still comical misunderstandings that caused grand gestures to fall flat. In the mid-afternoon, after several cavalry and infantry sallies back and forth, a Russian lieutenant-general who had been taken prisoner was brought before Napoleon. After having talked to him “very politely for a few minutes,” the Emperor said to someone standing nearby, “Give me his sword.’” A Russian sword was at once produced and handed to the Emperor. Taking it, then offering it to the Russian general, Napoleon intoned with all the gentlemanly gravity that such a moment demanded, “I return your sword.” As it happened, however, that was not the prisoner’s own sword, and, not understanding the honor the Emperor meant to do him, the Russian general refused to receive the weapon from the great man’s gracious hand. Napoleon, thunderstruck “at this lack of tact, shrugged his shoulders, and turning to [his officers] said, loud enough for the [man] to hear him, ‘Take the fool away!’”[30] [42] Little though it may have been, the story was indicative of the larger emptiness of the day. The Grande Armée had finally fought the grand battle that its commander had sought for months — but to an indecisive and costly end.

At last, night mercifully plunged the plain into shadow, and the Russians withdrew what was left of their army in somewhat good order. Behind them 94,000 men and horses lay strewn across the field of Borodino. In Napoleon’s words, it was “a battle of giants,” not of small wooden men or miniature tin figures. From a distance, however, their colorful, torn uniforms and tattered battle flags looked for all the world like the leftovers of a particularly gory party or fairground, filled with broken toys and limbless dolls. The duel had not transformed a “funny little” stranger into a conquering hero-prince; it seemed that it had taken a splendid prince, one whom all the world had feared and admired, and revealed him to be an aging, mortal man barely able to sit up and too afraid to send his Old Guard into the breach. The road to Moscow lay open, but it was a hollow triumph for the greatest general of all time.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “Paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

- Third, Paywall members have the ability to edit their comments.

- Fourth, Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected] [43]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[44]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[44]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.

Notes

[1] [45] After having read both versions, I favor Hoffmann’s for its originality (it was first, after all), richer irony, and the fact that its tone seems subtler and “adult,” and somewhat darker; that said, Dumas’ is also enjoyable, and his style makes for smoother reading.

[2] [46] E. T. A. Hoffman, The Nutcracker and the Mouse King (New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1853), 19.

[3] [47] “Marianne” is the feminine personification of France.

[4] [48] We now know, however, that Napoleon was not a short man for his time, his height 5’7” — the upper side of average for men in early nineteenth-century Europe. Thus, the pseudo-psychological slur, “Napoleon Complex,” is unjust and should be renamed the “Lenin Complex” immediately.

[5] [49] Hoffmann, 5-6.

[6] [50] Ibid, 24.

[7] [51] Ibid, 101, 34-35.

[8] [52] Ibid, 35-36.

[9] [53] A bit of irony here, I suspect.

[10] [54] A formation of squares used in defense.

[11] [55] Hoffmann, 44-46.

[12] [56] Ibid, 106.

[13] [57] The truly horrendous blood-letting on that score occurred in the early years of the nineteenth century, however.

[14] [58] The Grande Armée crossed over into what was then part of the Russian Empire, but what is now Lithuania.

[15] [59] Achilles Rose, Napoleon’s Campaign in Russia, Anno 1812; Medico-Historical Account (Project Gutenberg, 2005), 20. Dr. Rose takes a mostly dispassionate — and sometimes positive — view of Napoleon in this memoir of his medical service in the Grande Armée.

[16] [60] At this point (1812) the Romanov dynasty did not refer to themselves as “Tsars,” but “Emperors.” For the purposes of clarity, I refer to Alexander as Tsar Alexander I.

[17] [61] David G. Chandler, The Campaigns of Napoleon (New York: Scribner, 1966), 739. Perhaps the best single volume of Napoleon’s campaigns, told in the traditional military history style; even-handed and just; does not include the Peninsular Campaign or the naval battles, since Napoleon had minimal personal involvement in those arenas.

[18] [62] Eugène Labaume, A Circumstantial Narrative of the Campaign in Russia (London: Hartford, Hamlen, & Newton, 1817), 119. A singularly hostile diatribe against Napoleon.

[19] [63] Ibid., 119-120.

[20] [64] H. von Brandt’s account in Napoleon’s Untergang (Stuttgart), 66.

[21] [65] Quotation from Robert Wilson’s A Sketch of the Military and Political Power of Russia, in the Year 1817, 3rd ed. (London, 1817), 27.

[22] [66] This weird and occasionally deadly phenomenon was called “Wind of Ball.”

[23] [67] Quotation from Christopher Duffy’s Borodino and the War of 1812 (London: Cassel & Co., 1972), 111. This otherwise wonderful, close battle-study cannot pass up any chance to draw childish comparisons linking Napoleon to Hitler.

[24] [68] Rose, 23.

[25] [69] Duffy, 127.

[26] [70] Labaum, 67.

[27] [71] Ibid, 96-97.

[28] [72] Vasilïĭ Vasilevich Vereshchagin, 1812: Napoleon I in Russia (London: William Heinemann, 1899), 94. Told from a later Russian point-of-view; includes the author-artist’s wonderful illustrations.

[29] [73] Hoffmann, 39.

[30] [74] Labaum, 70-71.