Morrissey: The Last Romantic Poet?

Posted By Mark Gullick On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledI am the last of the famous international playboys. — Morrissey, song of the same name

Reggae music is vile. — Morrissey, 1980s interview

It began as one of those pub conversations about culture and art. You know how it is: Four or five guys (no chicks, please; they tend not to know much about music, and they are a distraction) not so much shooting the breeze as machine-gunning it. A few pints in, and the pack is baying about the best band or the best album or the best novelist or painter or anything to stay on the beer, and not to go what we call “top shelf,” which is where the spirits are kept behind the bar and is usually where the trouble starts.

This particular drunken squabble began with a discussion — if you can call several men shouting a discussion — about why there were no more Romantic poets after the blessed band of Milton, Wordsworth, Coleridge, Byron, Shelley, and Keats. I am not including Chatterton, who was a fraud and a punk and a bad poet and primarily known only for the famous 1856 portrait by Henry Wallis of the young poet’s rapidly cooling corpse, and which is on the cover of every bloody compilation of Romantic poetry ever published.

[2]

[2]You can buy Mark Gullick’s Bestest Boys here [3].

Anyway, debate had been entered into, and it’s all Eliot this and Hölderlin that, and I said, no, bollocks. No more Romantic poets? There is one still living. A couple of the lads even put down their drinks and looked at me closely. I backed up my claim. What about Morrissey? Well, that set the cat among the pigeons. We had what some would term the theme of a symposium until closing time.

I had always loved The Smiths since I saw them in 1984 in a college close to my university. They were a Marmite band (you love them or you hate them), but from the time I turned on a cranky and possibly steam-driven television set in Brighton in 1983 and saw the band perform “This Charming Man,” I was utterly hooked by the lyrics as much as the music:

Punctured bicycle on a hillside desolate.

Will nature make a man of me yet?

As I wrote of the late Mark E. Smith of The Fall (another Manchester band), who on earth writes lyrics like that? Then there was Morrissey’s haunting voice — melodically a one-trick pony, but the trick was a good one: a lisping, light baritone embellished by a genuine falsetto and unmistakable, like him or not. And his lyrics seemed to take place on a street corner where existentialism and expressionism meet and get on rather well. Wedded to the great melodic skill and virtuosity of co-writer and guitarist Johnny Marr, Morrissey and the band rode a short but effervescent wave of success.

Now, there has to be at least one Smiths aficionado reading this, and here I am concentrating on Morrissey’s lyrics as a solo artist. That said, and for the sake of the specialist, these are my ten favorite Smiths songs, in ascending order:

Reel Around the Fountain

Asleep

Sweet and Tender Hooligan

How Soon is Now?

Frankly, Mr. Shankly

What Difference Does It Make?

Please, Please, Please, Let Me Get What I Want

That Joke Isn’t Funny Anymore

Last Night I Dreamt Somebody Loved Me

I Know It’s Over

That’s that out of the way. Once the band had broken up acrimoniously in 1987, with litigation to follow and with one member’s heroin addiction doing what that terrible drug does to so many bands, Morrissey went solo, to simultaneous critical success and controversy. These are what I think are his ten best lyrics, again in ascending order.

“Used to be a Sweet Boy”

Morrissey writes a lot about childhood, and didn’t appear to have had a terribly happy one, if his autobiography is anything to go by. This is poignant without being schmaltzy:

Used to be a sweet boy,

Holding so tightly to Daddy’s hand.

But that was all in some distant land.

Blazer and tie,

And a big, bright, healthy smile.

Used to make all of our trials worthwhile.

Used to be a sweet boy,

And I’m not to blame,

But something went wrong.

All the grief of parental dysfunction is present in this short lyric, and Morrissey is both a great miniaturist and a teller of tales that are particularly familiar to those of our generation (at 63, he is a couple of years older than me). “Used to be a Sweet Boy” is a short lyric with repeated refrains. A bit like childhood, I suppose.

“Trouble Loves Me”

I suspect I like this song because of its familiarity in my life. It speaks to me, rather shamefully:

Trouble loves me.

Trouble needs me.

Two things more than you do.

The whole heart of the song is just that: You look for a lover, and it ends up being trouble:

Trouble loves me.

Walks beside me.

To chide me,

Not to guide me,

It’s still much more than you’ll do.

And there are those of us for whom trouble makes kin as it trots behind us through life like a puppy-dog tied to a string.

“Every Day is Like Sunday”

Possibly Morrissey’s most famous solo single, this is a perfect example of Morrissey’s (I want to say “quintessential”, but I hate that bloody word) Englishness, as we visit the beach, or the seaside, as the English call it:

Trudging slowly over wet sand

Back to the bench where your clothes were stolen.

This is the seaside town they forgot to close down . . .

Morrissey invites us to cream tea in a place where every day “is silent and grey,” a town “they forgot to bomb.”

Oh, sod it. Morrissey is quintessentially English.

“You Have Killed Me”

One thing I always liked about Morrissey was that he played the game before there was a game. The early 1980s was a strange time for the gay movement, and although it was a fairly open secret that Morrissey was gay, this was a decade or so before it practically became compulsory.

He was also open about being well-read, effete, and artistic — Oscar Wilde for the boomers. My sort of guy from the start, and here Morrissey combines his culture-vulture image with that dreadful feeling a person has when the one they so wished for, sought, and snared decides it’s time for the short goodbye;

Visconti is me.

Magnani you’ll never be.

I entered nothing and nothing entered me

‘Til you came with the key.

And you did your best but,

As I live and breathe,

You have killed me.

You have killed me.

Repetition of a line is hardly unique to Morrissey, but with some artists you get the impression that they couldn’t think of another line, whereas Morrissey repeats for emotional effect.

“Angel, Angel, Down We Go Together”

One of the great Morrissey titles — and we will visit some more later — this begins with a line that makes even seasoned fans of Mozza (his nickname in the music press) think: Oh, here we go again: sadness, depression and suicide. Same old same old.

Angel, don’t take your life tonight.

So far, so Morrissey. But then the lyric opens up alarmingly into why it is that some people become so ultimately desperate, and why you have to be able to tough out this world. Hell, as Sartre famously wrote, is other people:

I know they take it and they take it in turns,

And leave you nothing real for yourself in return.

And when they’ve used you and they’ve broken you

And wasted all your money

And cast your shell aside.

And when they’ve bought you

And they’ve sold you

And they’ve billed you for the pleasure,

And they’ve made your parents cry,

I will be here.

Oh, believe me.

Morrissey often writes from the first person, but the songs in which he addresses others — often with avuncular advice — are the most moving.

“Hold on to Your Friends”

The simplicity and honesty of this song is bracing and salutary. Friendship is a tricky thing to assess, and I am not sure there is a common denominator. A friend that one person likes may be hated by that fellow’s best friend, like a suit that fits one guy looks terrible on another. I am sure you will have had a friend who is just not another friend’s cup of tea. Our non-mutual friend. I know I have, and so have friends of mine, because it’s often me. But Morrissey pulls on the common thread of friendship:

There are more than enough

To fight and oppose.

Why waste good time

Fighting the people you like

Who will fall defending your name?

Don’t feel so ashamed to have friends.

You shouldn’t be shamed by a pop singer, but that line makes me very sorry about the times I have picked fights with those who are only trying to help me. Not that this song is just a guilty paean to the significant others in our lives; they can also hurt and irritate us:

Now you only call me

When you’re feeling depressed.

When you feel happy

I’m so far from your mind.

It is a grand reminder of the part that friends play in people’s lives. Finally, Morrissey reminds us — as though we needed reminding, which we do — that “there just might come a time when you need some friends.”

“Irish Blood, English Heart”

Morrissey’s political writing. Discuss. To me, he made an ass of himself on his first solo album with the closing track, “Margaret on the Guillotine.” It plainly referred to Margaret Thatcher — who I am still not a terrific fan of without wanting her head cut off — and possibly irritated me because my mother’s name happens to be Margaret. But by the time of “Irish Blood, English Heart,” I really felt Morrissey had politically matured.

Everyone in Britain or the United States — see Biden’s tomfoolery — claims to be part Irish, so I don’t see why I should buck this trend. My great-grandfather was a master carpenter in Dublin (a city I adore), so I guess I am part-Paddy. Maybe that’s why this lyric speaks to me:

Irish blood, English heart.

This I’m made of.

There is no one on earth I’m afraid of.

I am sure we would all like to believe that we fear no one, and Morrissey’s lyric here may “spit upon the name Oliver Cromwell” (who I have always rather liked), but the verse on Englishness has a shining relevance today:

I’ve been dreaming of a time

When to be English

Is not to be racist or hateful.

If there have been other artists who have used the word “racist” in a pop song, and weren’t whining about the whiteness of it all, please contact me at the usual address.

“Come Back to Camden”

Firstly, during my investigation of his back catalogue, so to speak, I have noticed that most of my choices are from Morrissey’s 2004 album You Are the Quarry, but I guess that just means I feel that was when he was at the height of his lyrical powers. But I have to put this song in the hit parade, because I miss London and I have had a long-standing love affair with Camden Town, that scuzzy little enclave of north London before the rich bits of St. John’s Wood, Hampstead, and Swiss Cottage begin. Camden is like that friend who phones you and suggests a drinking session — perhaps in Camden — and you think: fun or a night in jail?

Morrissey’s imagery here is evocative, and as London as Dickens or Big Ben, with his signature melancholy present and correct:

The tile yard all along the railings,

Up a discolored dark-brown staircase,

Here you’ll find despair and I . . .

The broken heart is found “drinking tea with the taste of the Thames,” and the song finishes with a plea:

Come back to Camden

And I’ll be good, I’ll be good, I’ll be good.

“The National Front Disco”

Morrissey was politically incorrect before this vague and woolly concept existed. He was criticized for various songs, the first being The Smiths’ “The Hand That Rocks the Cradle,” which concerns a subject which, in the United Kingdom, was thought untouchable. If you don’t know about the so-called “Moors Murderers,” Ian Brady and Myra Hindley, who were jailed for life in 1966 for the sexual murder of several children, can I ask you to look it up for yourself? It is one of the most callous and wicked murders in modern English history and some of the details are still upsetting.

Morrissey’s band — part rock and part rockabilly — deserve a mention in dispatches, and here they rev up like The Clash, as Morrissey plays the clever trick of singing about Britain’s most notorious far-Right political party (The National Front, some of whom were genuine thugs and nutters) while not appearing to endorse them. The sheer nerve of recording a song with the line “England for the English” and getting away with it is admirable. But the song is from the point of view of a father worried about his son becoming what we would call “radicalized”:

Your mum says,

I’ve lost my boy.

But she should know why you’ve gone,

Because again and again you’ve explained

You’re going to the National Front disco.

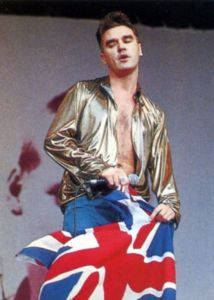

Morrissey was once trounced for playing a festival gig in front of a Union Flag. That was decades ago, and as you can imagine, the situation has not improved.

“First of the Gang to Die”

Morrissey has many obsessions — underground currents which feed the river of his work. One is gangs and gangsters, preferably teenage ones. The genius of this song is the casual (and yet classical) move from love to death as we switch from a beautiful opening line to something that reminds us of life’s horrors:

You have never been in love

Until you’ve seen the stars

Reflect in the reservoirs.

And you have never been in love

Until you’ve seen the dawn rise

Behind the home for the blind.

The scenario suddenly shifts to an atmosphere of menace and death:

We are the pretty, petty thieves.

And you’re standing on our street.

As the chorus arrives to tell us what these gangsters are up to, the brilliance of Morrissey is to choose a classical name for his young and doomed thug:

Hector was the first of the gang

With a gun in his hand.

The first to do time,

The first of the gang to die.

Such a silly boy.

I have a partly crazy drinking buddy here, a very talented Argentinian artist — he is very talented both at art and at being Argentinian — who inexplicably knows every Morrissey lyric there is. After I drank with him while watching Argentina beat Australia in the World Cup, we went into town and he got so rowdy I had to lose him. People usually do that to me. This is his particular favorite from the end of “The First of the Gang to Die”:

And he stole from the rich and the poor

And the not very rich and the very poor,

And he stole all hearts away.

[4]

[4]You can buy Mark Gullick’s Vanikin in the Underworld here. [5]

This is a thread in Morrissey’s imagery: Narcissus with a gun.

Morrissey is, I think, the undisputed champion of song titles, and certainly not many songsters have written them longer. He started well in The Smiths with such ditties as “Some Girls are Bigger than Others,” “Heaven Knows I’m Miserable Now,” “Stop Me if You’ve Heard This One Before,” and “The Boy with the Thorn in His Side.” But he was just getting started. His solo career features titles that would persuade you to listen to the song just for the name: “Pregnant for the Last Time”; “There’s a Place in Hell for Me and My Friends”; “Bengali in Platforms” (a song that got him into trouble with the usual suspects, but is hilarious); “You’re the One for Me, Fatty”; “I Have Forgiven Jesus.” Even if you hate the guy, there are many more titles where those came from here [6].

The last line I’ll quote from the Bard of Manchester is simple, and like all such things must be placed in context;

Is this the best place to wait for a taxi?

It could come from a Morrissey song but it doesn’t, although it was said by Morrissey. In the mid-1980s, myself and a friend, drunk as lords, were looking for a taxi after a fine evening in Covent Garden’s excellent Tex-Mex restaurant Café Pacifico (well, it was excellent then, I can’t speak for it now). We lurched out of Southampton Row and onto The Strand, the spot outside the pub The Lyceum Tavern being a good one to nab a cab. There was another man waiting, and it was Stephen Patrick Morrissey, who asked me the question above. I knew from the music press that he had recently moved to London and his face was all over the papers in those days. I told him yes, it was, and he said thanks, and we offered him the first cab that arrived, which he took with a smile — a charming man. And that was the extent of our conversation.

So, I am sticking with Morrissey as belonging to the pantheon, the last of the Romantic poets. He’s outlived most of them, that’s for sure.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “Paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

- Third, Paywall members have the ability to edit their comments.

- Fourth, Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected] [7]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[8]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[8]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.