Hitchcock vs. Visconti

Posted By Derek Hawthorne On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled6,135 words

Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958) and Luchino Visconti’s Death in Venice (1971) are both concerned with love and the ideal. If you love cinema, you will love these films, which I would rank among the greatest ever made. They can teach us a lot about love, idealism, art, and different sorts of desire. Be advised that there are a great many spoilers ahead.

Vertigo is the story of John “Scottie” Ferguson (played by James Stewart), a San Francisco policeman who retires from the force after a deadly rooftop chase [2] leaves him with severe acrophobia (fear of heights). An attack usually causes him to feel like his surroundings are spinning — hence the title, Vertigo. Scottie is hired by Gavin Elster (Tom Helmore), an old school chum who has married into money, to follow Elster’s wife, Madeleine (Kim Novak). It’s not the usual thing — Elster doesn’t suspect infidelity. In fact, the situation couldn’t be more unusual: Elster believes that his wife is possessed (either literally or figuratively) by the spirit of someone long dead. Her behavior is mysterious. She spends her days engaged in apparently aimless wandering, none of which she seems to recall later on.

Scottie accepts the job, then uses his detective skills to shadow Madeleine as she moves around San Francisco. We know there is going to be trouble, because when we and Scottie first set eyes on Madeleine [4], she is ravishingly beautiful. Scottie finds that she does indeed spend her days on a strange series of activities that seem unrelated and aimless. She buys a bouquet of flowers at a florist; she visits Mission San Francisco de Asís on Delores Street; she visits the art museum at the Legion of Honor; and she spends time at an old hotel where (according to the proprietor) she regularly rents a room, in which she merely sits for a time in silence.

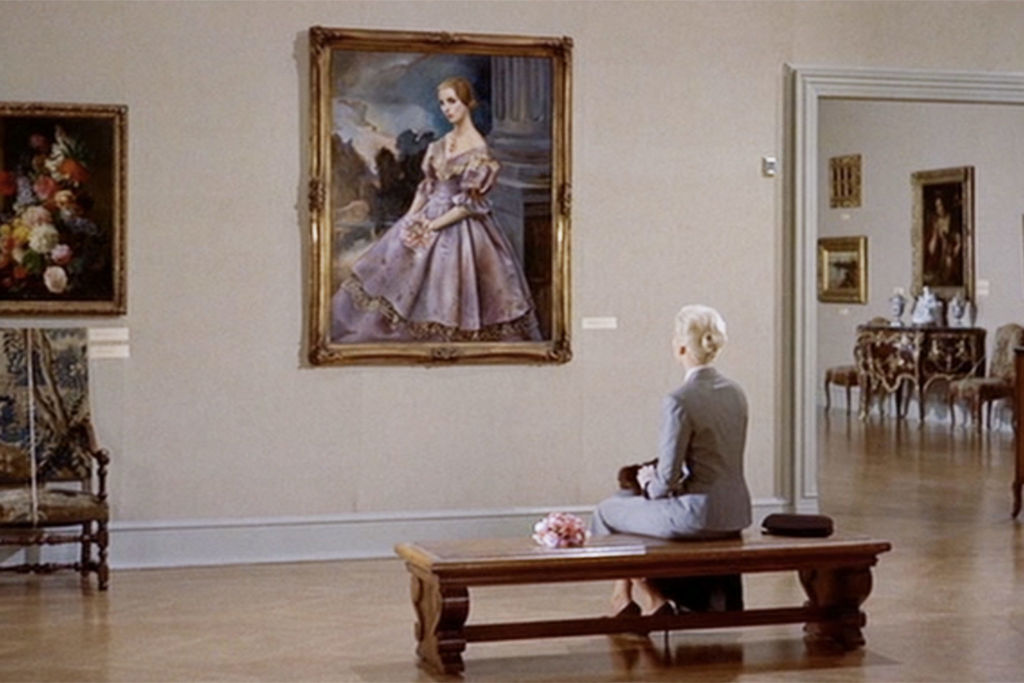

All these activities, however, are tied together by Carlotta Valdes, a woman who died in the nineteenth century. She had been the mistress of a wealthy man and bore him a child. The man kept the child but abandoned Carlotta — who eventually went mad and committed suicide. At the art museum, Madeleine spends all her time sitting and gazing at a painting [6] of Carlotta Valdes. The bouquet she has specially prepared at the florist is a replica of the one held by Carlotta in the portrait. At Mission Delores, she stands before Carlotta’s grave. And Carlotta lived at the same hotel Madeleine visits, probably in the very same room.

Scottie tails Madeleine for what may be a day, possibly more. Then he reports what he has found to Elster, who reveals that Carlotta Valdes was Madeleine’s great-grandmother. However, Madeleine herself has no knowledge of this, so the viewer is left to assume that the connection Madeleine feels to Carlotta is somehow supernatural. Scottie continues to follow Madeleine, and tails her to Fort Point, which is beneath the San Francisco side of the Golden Gate Bridge, with a magnificent view of the bay. Madeleine stands over the water, tossing in bits of her bouquet — then suddenly she jumps in [8]. Scottie rescues her, and it is obvious from his emotional reaction that he is falling in love with Madeleine.

Scottie takes the unconscious woman back to his apartment, where he relieves her of her wet clothes and puts her to sleep in his bed. She wakes with a start, and, satisfied that he is friend and not foe, they talk for a while before she abruptly leaves. The next day, Madeleine stops by Scottie’s apartment to leave him a thank you note. But she runs into Scottie himself, and they decide to spend the day together. Both, they acknowledge, are wanderers [10]. She wanders the city, possessed by some force of which she has no conscious knowledge. Scottie, having lost his one reason for being, his career as a policeman, wanders as well.

In an eerie and dramatic scene [11], Scottie and Madeleine visit the giant sequoias of Muir Woods. Then, they travel to Cypress Point on 17-Mile Drive where, by the ocean, they kiss. The next day, Madeleine meets Scottie and tells him of a nightmare she has had. Based on her description, Scottie identifies the setting of the dream as Mission San Juan Bautista, where Carlotta Valdes lived as a child. They drive there and Scottie expresses his love for Madeleine [12], who clearly returns his feelings. However, she then abruptly insists that she must go into the church, and go in alone. “It wasn’t supposed to happen this way,” she says mysteriously, then runs away from him and enters the old mission church.

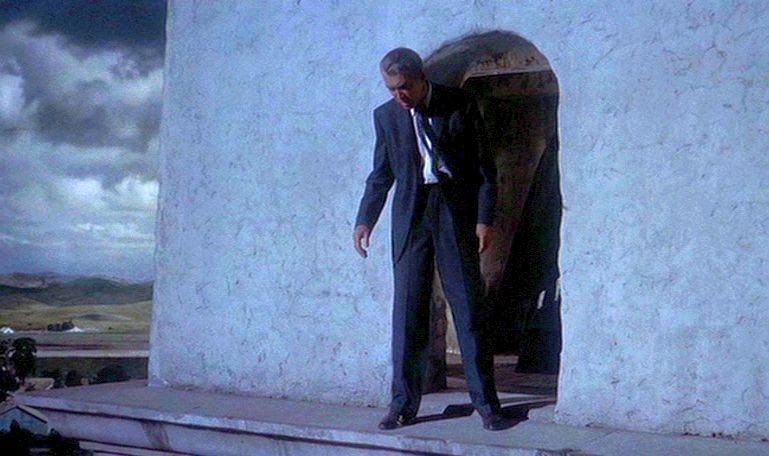

Scottie follows her and realizes, to his horror, that she is climbing to the top of the belltower. As he tries to follow her up the winding, wooden staircase he suffers an acute attack of vertigo [13], and is only able to make it part of the way up. Looking out a window, he sees Madeleine fall to her death. At the inquest [14] that follows, Scottie, now a broken man, is forced to endure the humiliation of being told that Madeleine’s death was caused by his “weakness.” Gavin Elster is present and tells Scottie that he doesn’t blame him. “You and I know who killed Madeleine,” he says, insinuating that the spirit of Carlotta is really to blame.

In the aftermath of Madeleine’s death, Scottie’s mental condition deteriorates. Following a terrible nightmare [16], he suffers a complete nervous collapse and is hospitalized in a semi-catatonic state. When released, he is far from “cured.” Scottie remains obsessed with Madeleine, visiting their old haunts, once mistaking a woman on the street for his dead love. Finally, one day he runs into a girl who does in fact bear a striking resemblance to Madeleine. However, her hair is dark, her eyebrows heavy, and her manner unrefined. Predictably, Scottie follows her back to the hotel where she lives and, in a pathetic scene, pressures the girl into having dinner with him. She tells him that she is Judy Barton (also played by Kim Novak), from Salina, Kansas.

As soon as Scottie leaves, promising that he will pick her up in an hour, Judy appears distressed. Accompanied by a flashback, she sits down and writes Scottie a letter, revealing that it was she who had been pretending to be Madeleine the entire time. Judy had been Gavin Elster’s mistress, and he had enlisted her in his plot to kill his rich wife, due to their resemblance. Knowing that Scottie’s acrophobia would prevent him from reaching the top of the mission belltower, Elster had hidden there with the body of his dead wife (presumably murdered recently and on the spot). It was the body of the real Madeleine Elster that Scottie had seen falling from the tower, thrown by Gavin. He and Judy had remained there hiding, until the police and bystanders all left. Scottie was set up to be the witness who could testify to Madeleine’s deranged state of mind. Judy confesses her love for Scottie in the letter and says that she is leaving town, never to see him again.

However, no sooner has she written the letter than Judy decides against it and tears the thing up. She can’t deny her love for Scottie, and is willing to recklessly enter into a relationship with him, with no idea of whether or how she will ever reveal her terrible secret. This creates the suspense in the remainder of the film’s events, which can be very briefly summarized. Scottie seems deliriously happy with Judy, and the two begin to spend more and more time together, visiting lovely San Francisco locations (it is so sad to watch this film and to think about what the city has become). Though things start out well, over time Scottie begins trying to make Judy into Madeleine [19].

He begins with her wardrobe, finding exact duplicates of Madeleine’s chic suits and gowns for Judy to wear. Judy resists this the entire time, asking Scottie to love her just as she is. But he implores her to accede to his wishes. “If I do what you tell me, will you love me?” Judy asks, plaintively. This whole process culminates in a trip to the beauty parlor, where her makeup is changed to mimic Madeleine’s and her hair bleached. Scottie waits for Judy at her hotel room. When she enters, she is wearing her hair long. He insists that she pin it back from her face, as Madeleine did, and Judy disappears into the bathroom to comply. When she emerges, it is as if Madeleine has returned from the grave. He embraces her and they kiss passionately as the camera moves in a circle around them, and as Scottie has a flashback to their embrace in the stable at Mission San Juan Bautista. It is the most famous scene in the film [20], and one of the most famous in all cinema. The unstated implication is that, so far, their relationship has gone unconsummated, with Scottie unable to perform sexually unless he sees the exact image of Madeleine.

Following this, Judy seems to accept her new role as imitation Madeleine, and all seems to be going well — until one night. Judy is dressing for dinner and chooses a necklace that Scottie recognizes as the one worn by Carlotta in her portrait. Scottie instantly intuits exactly what has happened. On the pretext of taking them to dinner, Scottie drives Judy all the way to Mission San Juan Bautista. There, he revisits the scene of “Madeleine’s” death — and conquers his acrophobia. Scottie practically drags Judy to the top of the belltower, all the while piecing together Gavin’s plan — and Judy confesses everything. However, it emerges that she was a reluctant participant, who Gavin tossed away once the deed was done — just as another wealthy man had tossed away Carlotta Valdes. He left her some money, and Carlotta’s necklace,[1] [22] then fled to Europe.

Judy professes her love for Scottie. “When I saw you again, I couldn’t run away. I loved you so!” she says. “I walked into danger and let you change me again because I loved you and wanted you!” But Scottie seems unmoved: “It’s too late,” he says. “There’s no bringing her back.” At just this moment, Judy reacts with horror to a figure emerging from the shadows behind Scottie. She begins backing away from him, moving perilously close to the edge of the unrailed tower. The figure turns out to be a nun. “I heard voices,” she says — just as Judy slips and falls from the tower with a terrible scream. Scottie stands at the edge, looking down from the tower (presumably at Judy’s body), in shock. FADEOUT. THE END.

There’s so much to say about this film, and perhaps one day I’ll devote an entire article to it, but in the present essay I am going to limit myself to my theme of “love and the ideal.” When Scottie first sets eyes on Madeleine, there is no real woman in his life. He is friendly with a girl named Midge (Barbara Bel Geddes), with whom he had once been engaged. Midge is quite pretty, smart, capable, and still very much in love with Scottie — but somehow she’s just not good enough for him. (The poor girl doesn’t even get a mention in my plot summary.) In Madeleine, however, Scottie seems to have found his ideal woman.

This phenomenon of searching for the “ideal woman” or “ideal man” is quite real. Though you wouldn’t know it from the choices many people make, those are folks with “lowered expectations [26]” (which is reasonable in most cases). And sometimes the ideal man or woman functions in the mind of the lover as the ideal. In such cases, the beloved never ceases to be man or woman, but the ideality that shines through them has no sex: it is the Beautiful, the Good, etc. I will argue that this is what Tadzio is for Aschenbach in Death in Venice. But what is Madeleine for Scottie? The ideal or merely ideal woman? Hard to say. His love for Madeleine certainly doesn’t seem like the love of Dante for Beatrice, who takes on a semi-divine status in Dante’s poetry. Scottie’s love for Madeleine is carnal — and I will court controversy a little later by arguing that the love of Aschenbach for Tadzio is not carnal at all (it is the Aschenbach-Tadzio relationship that, of the two stories, comes closest to the Dante-Beatrice relationship, despite the fact that the sexes are the same).

The problem with Madeleine is that she isn’t real. Scottie has found his ideal love, but she is all illusion. She is Judy made over into Madeleine through a wardrobe change, makeup, bleach, and an expensive coiffure. Cynics will say that this is always true of the ideal — that it is always illusion; something we are tricked (or trick ourselves) into believing. We’re so attached to the ideal that if we feel we have lost it we will engage in all sorts of self-deception to get it back again, as Scottie does in the latter half of the film. (This is what “theology” is all about, by the way.) Was Hitchcock this cynical? I suspect that he was, though Hitchcock seldom made “philosophical” statements.

Commentary on Vertigo often deals with how the character of Scottie mirrors Hitchcock — especially the Hitchcock of the early sixties, who became obsessed with actress Tippi Hedren, nurtured an unrealistically idealized image of her, and sought to make her over. Predictably, academic criticism has been heavy on the feminist angle: Scottie is a “stalker” who directs his “male gaze” on Madeleine/Judy and seeks to obliterate her autonomy (or something). However, I don’t know of anyone who has stated the obvious: Vertigo contains what may very well be Hitchcock’s thoughts on the nature of woman.

Coiffured, made up, hair dyed gold, dressed to the nines, and “finished” with posh manners, woman presents herself to man as an ideal — which he then pursues to the point where he loses all reason. Underneath all this artifice, however, she is just Judy from Salina, Kansas: dull brunette, heavy of brow, a bit coarse, a bit “easy” (“I’ve been on blind dates before. Matter of fact, to be honest, I’ve been picked up before,” she says to Scottie), with nothing much interesting to say (“I’m just about ready. All I’ve gotta do is find my lipstick. Where did I put it? I had it a minute ago. I wonder if it’s here. Here it is.”) The reality is uninspiring, but man is a romantic who cannot accept that ideal woman doesn’t exist. So, he has no choice but to become an artist and to fashion Madeleine, Pygmalion-like, out of the dull clay that is Judy — sometimes if only in his imagination.

I’m not offering this as my view of woman, or of men and women, but a plausible case can be made that it was Hitchcock’s. Indeed, what he presents in his films is not realistic at all. He gives us an idealized representation of woman and everything else: an idealized Vermont in The Trouble with Harry, an idealized California fishing village in The Birds (where everyone speaks with a different accent), an idealized representation of the American moneyed class in Marnie (who seem indistinguishable from the English gentry), an idealized London in Frenzy (drawn more from Hitchcock’s childhood memories than from the realities of Britain in the early seventies), etc. Like Ayn Rand’s conception of “Romantic realism,” Hitchcock’s art presents life “not as it is, but as it might be and ought to be.”

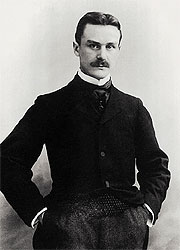

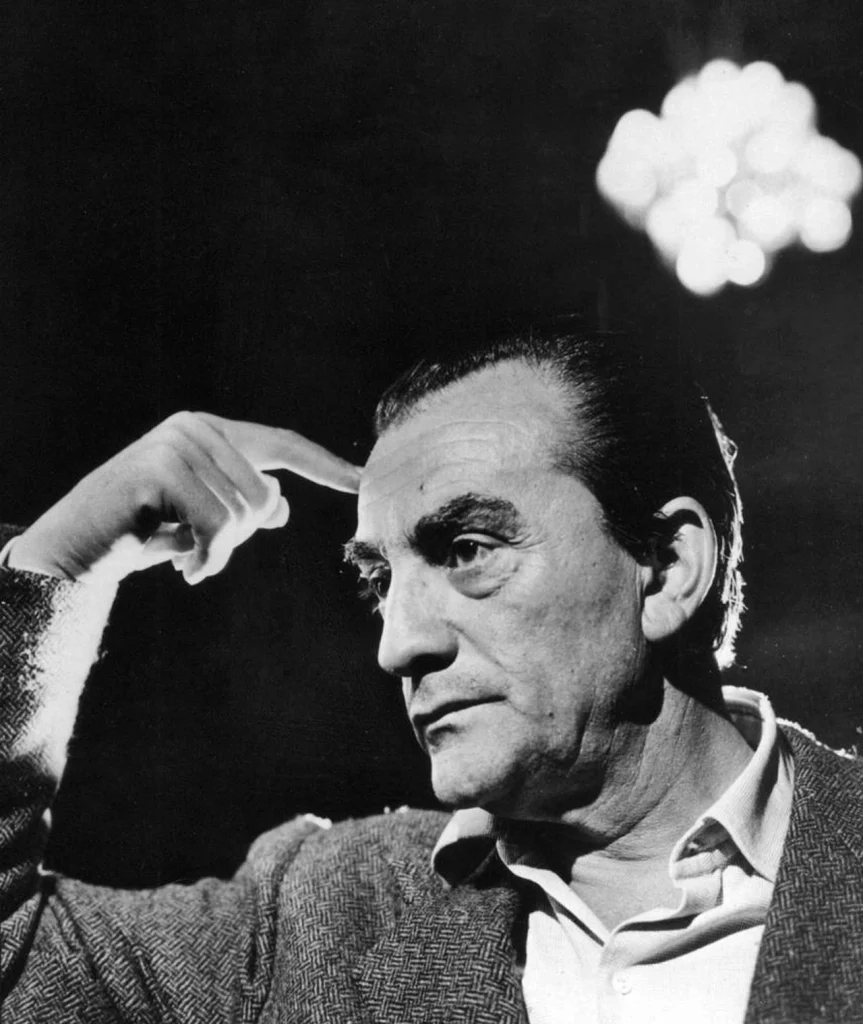

I will return to Vertigo later, but for now let us consider Death in Venice, which also deals with a man’s pursuit of an ideal. In this case, however, the ideal is real; it actually exists and is not the result of artifice. Based on the novella by Thomas Mann, the story takes place around 1911 and centers on Gustav von Aschenbach (Dirk Bogarde), a successful composer who has had a nervous breakdown following a disastrous premiere (in the novel the character is a writer). The middle-aged Aschenbach is advised to take a long holiday to recuperate, and so, weary with life and feeling his creative energies drained, he heads to Venice [27]. On the boat he encounters an old man grotesquely made up to look much younger and who cavorts with a group of youths, desperately trying to act like he is one of them. Aschenbach regards him with disgust.

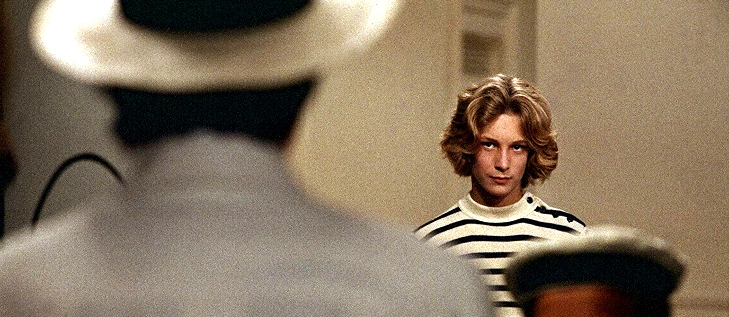

After docking, he makes the mistake of hitching a ride with an unlicensed gondolier. To Aschenbach’s consternation, the man insists on rowing him to the Venice Lido — Aschenbach’s ultimate destination, but not where he wants to go first. When the man refuses to turn the gondola around, Aschenbach has no choice but to submit to the unwanted journey. (This is obviously an appearance of Charon, the ferryman who carried souls across the river Styx to Hades — one of many allusions to Greek myth in Mann’s novel.) Aschenbach checks into the Grand Hotel des Bains and, after dressing for dinner, he heads to the salon to read a German newspaper. Bored with the paper (as, it seems, with everything else), he notices an aristocratic Polish family seated nearby [29]: a beautiful and very elegantly-dressed woman (Silvana Mangano), with her three small daughters and only son (Björn Andrésen), who looks to be about 14.

The boy’s name, we soon learn, is Tadzio, and he is dressed in a sailor suit. Tadzio immediately catches Aschenbach’s eye, because he has an androgynous, and genuinely angelic, beauty. Bemused, perhaps at his own reaction, Aschenbach continues to watch Tadzio until the ushers have announced that dinner is served and almost everyone has left for the dining room. As Tadzio exits, he turns and looks directly at Aschenbach, thus confirming that he knows he was being observed. The look is often described as “alluring” or of the “come hither” variety — but we should be careful about this. At the very least, we should note that “alluring” and “come hither” may have a significance other than sexual (I will discuss what I mean by this later on). Visconti has been accused of distorting Mann’s vision by including this, and a number of other moments when Tadzio returns Aschenbach’s gaze. But the novel does include several moments like this. Visconti’s only change was to introduce these earlier in the story, and more often.

In the dining room, Aschenbach seems unable to summon much enthusiasm for eating. Shortly after sitting down at his table, he moves aside a small vase of flowers so that he can continue looking at Tadzio. As he does so, we hear, in voiceover, a conversation between Aschenbach and a character called “Alfred” (Mark Burns), who appears throughout the film in flashback, arguing with Aschenbach about artistic and philosophical matters. He may be a close friend, or the composer’s brother — the film simply doesn’t make this clear. Alfred has just denied Aschenbach’s claim that the artist creates “from the spirit” — which means from something in us (the soul, or possibly intellect) that occupies a higher realm than the senses and the body. Alfred pours scorn on Aschenbach’s reference to the artist “laboring” to create beauty. And, just as Visconti’s camera focusses closely on Tadzio, we hear Alfred saying, “That’s how beauty is born. Like that, spontaneously. In utter disregard for your labor and mine. It preexists our presumption as artists.”

This is, in fact, the whole point of the story. Death in Venice is notorious, both as novel and as film, for its depiction of a man’s obsession with a boy. Today’s readers and audiences, with their overly simplistic understanding of love, sex, art, and everything else, peg this as a story about pedophilia. But this was not Mann’s intention. There is no suggestion in the novel or the film that Aschenbach actually wants to sexually possess Tadzio. Interestingly, the story was inspired by real events in the life of Thomas Mann. These are best left summarized by Mann’s own wife, Katia:

All the details of the story . . . are taken from experience. . . . In the dining-room, on the very first day, we saw the Polish family, which looked exactly the way my husband described them: the girls were dressed rather stiffly and severely, and the very charming, beautiful boy of about 13 was wearing a sailor suit with an open collar and very pretty lacings. He caught my husband’s attention immediately. This boy was tremendously attractive, and my husband was always watching him with his companions on the beach. He didn’t pursue him through all of Venice — that he didn’t do — but the boy did fascinate him, and he thought of him often.

Prior to this encounter in Venice, Mann had become captivated by the story of the 72-year-old Goethe’s love for Baroness Ulrike von Levetzow, who was 17 at the time. Mann was inspired by this to write a novel about “passion as confusion and degradation,” though he had not worked out the details. Mann’s experiences with “Tadzio” in Venice gave shape to the story. He decided to leave the love object a boy, just as in his own experience, because he thought that if it were a young girl, readers would automatically assume that Aschenbach was moved purely by sexual desire. By making the love object a boy, he thought that readers would be forced to give the relationship a subtler reading. (“That didn’t age well,” commented a friend of mine, when I told him of this.)

In his decision, Mann was clearly drawing on the rather idealized view of Greek “boy love” common to writers of his generation. The truth is that “boy love” did involve the idealism that has been attributed to it — but at the same time it was frequently sexual. As a professor of mine put it years ago, “The thing about Platonic love is that it wasn’t all that platonic.” But this more realistic perspective was evidently not Mann’s. The film also establishes that Aschenbach is “straight.” In flashbacks, we are introduced to Aschenbach’s wife (Marisa Berenson), now dead. That their only child, a daughter, is also dead is established in another flashback scene, filled with raw emotion. In a further flashback, Aschenbach is depicted as frequenting a brothel. It must be admitted that the film does have a certain “gay sensibility” due to the fact that Visconti was gay, as was Bogarde (who plays Aschenbach as somewhat fey). But Visconti was an intellectually sophisticated filmmaker who understood the story he was dealing with. He would have been appalled had he lived to see the British Film Institute rank Death in Venice as the 27th greatest “LGBT film” of all time [34].

What Death in Venice is really about is the conflict of the Apollonian and Dionysian understandings of art and beauty. Mann was familiar with this distinction, formulated by Nietzsche in The Birth of Tragedy. In the story, Aschenbach represents the Apollonian artist: He believes that the artist not only must labor to create beauty, but that this creation must involve clear-headed calculation. The artist, for Aschenbach, must subject himself to a severe discipline in order to create. In the film, the Dionysian alternative is championed by Alfred. “Beauty belongs to the senses,” he tells Aschenbach, who counters that “it’s only by complete domination of the senses” that anything great can ever be achieved by the artist. Alfred describes artistic genius as “a divine affliction,” and as “a sinful, morbid flash fire of natural gifts.”

The Dionysian view of creativity is that one must surrender oneself to the senses, to the irrational, to nature. And, in Death in Venice, the Dionysian wins. What Aschenbach encounters in Venice is a living, breathing refutation of his entire life’s work, and a confirmation of what his friend and interlocutor had been saying to him all along. In Tadzio, Aschenbach discovers an object of pure beauty — the beauty he had striven all his life, largely in vain, to create in his music. Here, that beauty is made flesh. Tadzio is not the result of calculation, labor, or discipline. He is one of nature’s mysteries, a happy accident, and the holder of an extremely lucky ticket in the genetic lottery. Like a bacchant, Aschenbach surrenders himself to the worship of this god — and, in the process, surrenders reason, dignity, and his very life.

The rest of the story can be told fairly briefly, as the plot of Death in Venice is much simpler than that of Vertigo. Aschenbach’s interest in Tadzio soon develops into an obsession. Disturbed, he hastily packs and decides to leave Venice [37]. At the railway station, however, he learns that his trunk has been misdirected to Como. Feigning outrage, Aschenbach seizes upon this as an excuse to stay in Venice [38], and is evidently quite pleased with this outcome. Returning to his hotel, he gazes out the window of his room and spots Tadzio on the beach. Aschenbach raises his hand in greeting, though Tadzio does not see him. At this point, Aschenbach conveys the quality of an addict who has abandoned all attempts to quit and has now surrendered himself completely to the drug.

He begins to follow Tadzio and his family all over Venice. At a certain point, it becomes clear that they have noticed his interest and are wary of him. And Aschenbach has noticed something himself, something which he finds quite disturbing: City workers are applying a disinfectant wash to the streets. He makes inquiries and is assured that nothing in Venice is amiss. However, a British travel agent privately informs Aschenbach that in fact the city is in the grip of a cholera epidemic. Officials have not warned the public, because they are afraid it would frighten away the tourists. Aschenbach indulges in a brief reverie in which he warns Tadzio and his family of the epidemic and urges them to leave. This fantasy sequence ends with Aschenbach extending a trembling hand to stroke Tadzio’s hair. However, he decides not to warn the family — for it would mean that he would lose Tadzio! So obsessed is Aschenbach that he is willing to risk the boy’s life, and his own, for a few more days of voyeurism.

Aschenbach visits the hotel barber [40], who persuades him to allow his hair to be dyed, his face painted with pancake, and his lips colored bright red. The barber is a slippery, serpentine character. “You’re much too important a person to be a slave to conventions about nature and artifice,” he says. “You know, sir, we are as old as we feel, but no older. You, for instance, signore, have a right to your natural color.” The result is a grotesque simulacrum of the foppish old man Aschenbach had seen on the boat to Venice. In Vertigo, the love object is made over through “artifice”; in Death in Venice it is the lover who submits to this process. Why?

On one level, it is obviously to make himself more appealing in the eyes of Tadzio. But this seems pointless, since Aschenbach has to be aware that he will never get any closer to Tadzio, whose family are only in Venice for a brief holiday anyway and will soon be returning to Poland. No, what really motivates Aschenbach here is a horror of his own aging body — a horror prompted by his encounter with ideal beauty. And ideal beauty can never be imagined as old. At a certain point late in the film, Visconti inserts a close-up of Tadzio, long blond hair blowing in the wind, over which we hear the voice of Alfred saying, “In all the world, there is no impurity so impure as old age.” Aschenbach is desperately, foolishly trying to come closer to the ideal. Since he can come no closer to Tadzio, he tries to come closer in his own person. The result is, at last, the complete loss of his dignity [42]; Mann’s theme of “passion as degradation.” Aschenbach, however, is unashamed: he has sacrificed himself to the god whole — heart, body, and soul.

One morning, Aschenbach goes to the lobby of the hotel and discovers that the Polish family will be leaving later that day. Exhausted, physically and emotionally, he heads to the beach and sits in a deck chair facing the water [43]. There, he sees Tadzio in the distance, accompanied by an older boy (who, it is suggested earlier, may have more than a platonic affection for Tadzio). A fight breaks out between them, and Tadzio angrily skulks off and moves further towards the horizon. But he is aware of Aschenbach’s presence. Tadzio briefly turns to look at him, then turns away towards the Sun. In evident distress, Aschenbach watches. He begins perspiring from the heat, so that the dye in his hair streams down his temples and the white makeup begins to crack. With one hand on his hip, Tadzio raises the other to point at the Sun. Aschenbach stretches his hand out towards Tadzio — then collapses in the chair, dead. FADEOUT. THE END. (The cause of Aschenbach’s death is never clearly stated in the film, but we are left to assume that it is cholera.)

Despite many superficial differences, Scottie and Aschenbach have a lot in common. Aschenbach, of course, is the Apollonian artist, bent on creating beauty through careful planning, discipline, and the “complete domination of the senses.” But Scottie is also a control freak. Reserved and detached, he always remains at a safe distance, especially when following people. As a policeman, he is a student of human nature, accustomed to regarding everyone’s words and actions with suspicion. Like Mr. Hitchcock, in fact, he is a highly self-controlled observer of life. The onset of his acrophobia is as disorienting for Scottie as the vertigo it induces, for it means a loss of control — and with it, a loss of identity through his forced retirement. Scottie’s life continues to spin out of control when he falls head over heels for Madeleine. In this, he becomes as helpless as Aschenbach, following Madeleine through San Francisco as Aschenbach follows Tadzio through Venice — and finally losing his sanity, and his dignity.

Scottie attempts to regain control by making Judy over into an image of Madeleine. What he is not aware of, however, is that he is creating an image of an image – not an image of anything that actually existed. “Madeleine,” too, was illusion, a simulacrum of Elster’s wife, who we never actually meet. This idea of an “image of an image” immediately calls to mind Plato’s Republic in which it is argued that art distances us from truth, because its images represent objects that are themselves mere “images” of eternal forms or ideas. In that dialogue’s “allegory of the cave,” one man discovers that the objects of his experience are only images of images, by climbing a very great height and escaping from the cave.

Scottie, too, must climb a great height to discover the truth. A Platonic interpretation of Vertigo would have to also draw on The Symposium, and Diotima’s ladder of beauty. The first stage on the ascent is getting beyond identifying beauty with bodies alone — beautiful human bodies. Scottie’s fear of heights is, on the Platonic reading, a fear of leaving behind the body and ascending to another spiritual level, where Scottie would be yielding to the unknown and thus surrendering control. In the end, however, he accomplishes the ascent and receives the revelation. “There’s no bringing her back,” he says — knowing in this moment that the ideal he had sought in carnal form does not exist, and that his efforts to create it have been worse than futile.

Ashenbach undergoes a similar apotheosis. He thought he had found the ideal of beauty in Tadzio — and, as I argued earlier, at least Tadzio, unlike Madeleine, was real and not the result of artifice. But on the Platonic reading, Tadzio, too, is merely an image of the ideal, not the ideal itself. And the film’s final scene makes this explicit. In Aschenbach’s last glimpse of Tadzio, the boy points away from himself towards the Sun — symbol in The Republic of the Good, which transcends all finite individuals (including the Sun) and is “convertible” with the Beautiful. It is as if Tadzio is saying, “I’m not it. Look beyond me.” Platonic idealism seems to be the very essence of the Apollonian. But in this final, brilliant scene, Visconti transcends the Apollonian and the Dionysian. There is an ideal — but it is only achievable in ecstasy. And whatever object you may choose that provokes such ecstasy, whatever you are moved to identify as “the beautiful” is still not it. There is always more — an overflow, a divine excess, beyond whatever finite object we favor.

And all we can ever do is reach for it, as Aschenbach, in his final moments, reaches for Tadzio — reaches, but never grasps. Enlightenment is surrendering to the fact that you will never reach this infinity. In this realization, Aschenbach dies happily. Tadzio is depicted, essentially, as a muse, as an agent of the divine who draws Aschenbach toward the ideal. This is the true meaning of the “alluring,” “come hither” looks that Tadzio gives Aschenbach throughout the film, and which have often been attacked by dull-witted critics.[2] [45] Tadzio is indeed saying “come hither.” He is saying “follow me” — not to bed, but to the ideal of true Beauty Aschenbach had sought all his life. In the end, he guides Aschenbach to his final destination: beyond Tadzio to the eternal, elusive divinity of which Tadzio has all the while been only a reflection. And Tadzio carries him over the horizon, as Aschenbach discards his mortal body so as to commune directly with the ideal.

If you’ve not seen these films — and if your taste hasn’t been corrupted by the mindless, juvenile, ultra-fast-paced twaddle that passes for cinema today — you owe it to yourself to see both. They are like great novels: Every time they are revisited, one notices something new. But be warned: Both films cast a strange spell. You may have sensed this from reading my summaries. Vertigo is one of the most melancholy and tragic films ever made. The love of Scottie and Madeleine/Judy, the cinematography, and Bernard Herrmann’s Wagneresque score are painfully beautiful. Vertigo is a film about obsession that actually inspires obsession. Film buffs and Hitchcock fans often report having watched the film dozens of times. I can’t handle that much Vertigo; the film puts me in such a strange mood, I generally only watch it once every few years (I’ve seen it in re-release twice on the big screen).

Death in Venice is an equally haunting film — especially for anyone who has reached middle age (or beyond). Like Vertigo, Visconti’s film is a visual feast, though the style is markedly different from Hitchcock’s. Both directors are obsessed with detail, and shots are perfectly composed (both films are master classes in moviemaking). However, Vertigo has a quality that is very hard to describe; it has a kind of unreality. Though both films used the same color process, Vertigo often doesn’t seem like film at all. Similar to one of the Powell and Pressburger productions (The Red Shoes or Black Narcissus), every frame looks like a painting. And while Visconti was at least as much of a control freak as Hitchcock, the control comes through more with Hitchcock, as the whole film feels luminously artificial. By contrast, Visconti’s film makes us feel like we are glimpsing Venice in 1911 through some kind of time machine. Though it was meticulously planned, Death in Venice feels more real and more natural. The film also makes inspired use of the Adagietto from Mahler’s Fifth Symphony. Indeed, the film is widely remembered for this.

* * *

Like all journals of dissident ideas, Counter-Currents depends on the support of readers like you. Help us compete with the censors of the Left and the violent accelerationists of the Right with a donation today. (The easiest way to help is with an e-check donation. All you need is your checkbook.)

For other ways to donate, click here [48].

Notes

[1] [49] Since the necklace never appears anywhere in Vertigo except in Carlotta’s portrait, this must mean that Madeleine Elster really was the granddaughter of Carlotta, and that this part of Gavin’s story was not invented. The necklace must have been a family heirloom.

[2] [50] For example, upon the film’s release Roger Ebert wrote, “I think the thing that disappoints me most about Luchino Visconti’s Death in Venice is its lack of ambiguity. Visconti has chosen to abandon the subtleties of the Thomas Mann novel and present us with a straightforward story of homosexual love, and although that’s his privilege, I think he has missed the greatness of Mann’s work somewhere along the way.” Ebert was never the brainiest of film critics, and has missed all the subtleties of Visconti’s adaptation.