Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio

Posted By Margot Metroland On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledThree years ago I did a semi-humorous, shaggy-dog piece about Pinocchio and the Fascisti (“Pinocchio: The Face of Fascism [2]“). Its jumping-off point was talking about several Pinocchio films in the works, particularly a long-awaited stop-motion animation feature directed by Guillermo del Toro and Mark Gustafson. The film was then scheduled for release on Netflix “next year” (i.e., 2021) and was said to be very dark in theme. This darkness, we were told, lay mostly in its being set in Fascist Italy. There would be bombing and violence and cameos of Benito Mussolini.

Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio (for such is its full name) finally dropped in December 2022. Like the curate’s egg, it’s excellent in parts. It is truly dark in the sense that most scenes are in twilight or have an available-light look. Gustafson’s stop-motion is superb, and the set design is often breathtaking. The script is imaginative and original, though often cluttered with puzzling elements and subplots. There are two very well-done scenes of bombers flying overhead, seen from below in silhouette, but with the falling bombs themselves drawn in detailed close-up, followed by extended scenes of destruction and carnage. These seem to be inspired by old newsreels of the London blitz, though a closer model may be the bombing of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War.

Yet this is ostensibly Italy in the 1930s or even 1920s, and you have to ask: Why the bombing? I’ve seen it said that the first instance actually depicts Austro-Hungarian bombers in the Great War; looking this up, I find there were in fact some bombing missions, mainly around Venice. But this scene still seems a stretch, as the narrator tells us it was all an accident. I suppose these bombing scenes were beautiful in storyboard and, once filmed, too gorgeous to cut — however confusing and unlikely. All that glorious fire and destruction musn’t go to waste.

Much of the script is like this. We get brilliant little set-pieces that are there for show, not for continuity.

Unlike the 1940 Disney version, which kept most of the basic storyline of the 1883 Carlo Collodi book, this Pinocchio isn’t really based on the original source. No, it’s rather more like a vaguely remembered notion of the 1940 Disney film, passed through a game of Telephone. We start with a wooden puppet who is often naughty, and he has a woodcarver “father,” Geppetto, and they get separated but finally discover each other inside a giant fish. There’s an island where bad boys go and get punished. There is also a blue fairy who transforms Pinocchio into a “real boy” at the end. And then you have a loquacious, didactic cricket.

Those are the basic elements that remain in this Pinocchio script. They got strung together here, and then shaped and stuffed into a new story with all kinds of novel plot devices. To help hold it all together, we have a narrator in Mr. Sebastian J. Cricket, a literary insect who speaks with the voice of Ewan McGregor and sometimes sings, though he looks nothing like Jiminy. He is dark blue and grotesquely detailed, like a giant ant in a 1950s sci-fi flick. The blue fairy (Tilda Swinton) is even weirder, a shape-shifting “wood sprite” who appears variously as a lizard-like alien or monstrous blue griffin or dragon.

The script’s most extensive invention comes at the beginning, in a long backstory of how and why Pinocchio, the puppet, came to be. Now, in the book he begins as a talking log who talks back when Geppetto tries to chop him, while in the Disney version he’s a cute toy created by a merry Tyrolean craftsman who specializes in cuckoo clocks. In the del Toro film, the puppet is created as a replacement for Carlo, Geppetto’s beloved son who got killed when bombers dropped their payload on the local church, while little Carlo was standing inside, in rapt contemplation of the crucifix that Geppetto had built. Years later, in a drunken rage, Geppetto chops down the memorial tree by Carlo’s grave and makes it into an ungainly wooden puppet — you know, the kind you make when you’re drunk.

[3]

[3]You can buy Trevor Lynch’s Part Four of the Trilogy here. [4]

The religious aspect is another new embellishment. There are no churches or pietistic allusions in the book. It’s set in a secular, middle-class post-Risorgimento Italy without any reference to popes or kings or nobles. But here in the del Toro film we have a grand church edifice that figures heavily in the first act. It is bombed and destroyed, yet rises again. Somehow Geppetto’s giant crucifix survived the bombs and hangs once again above the altar. Unfortunately, Geppetto’s grief and drunkenness have kept him from finishing the painting of this masterwork. The unfinished crucifix is a sore point with the grumpy, nagging, unsympathetic pastor, a recurring character in the first half of the movie. Another point of contention is the unruly and mischievous Pinocchio, who misbehaves in church. The priest comes by one day with the local Fascist official (“Podesta”) to browbeat Geppetto for this and other things.

I suppose the screenwriters’ rationale for adding all the church business was, “Hey, this is Italy. They have some fine old churches in Italy, don’t they? So let’s put one in as realistic detail. And then we can add a mean priest, too, and imply he’s pro-Fascist.” Likewise, the very pretty set of Geppetto’s mountaintop town is basically a tourist’s idea of a medieval city in Tuscany or Umbria. Not exactly wellsprings of Fascism, which was rooted mainly in the north, in places like Milan and Mussolini’s native Romagna.

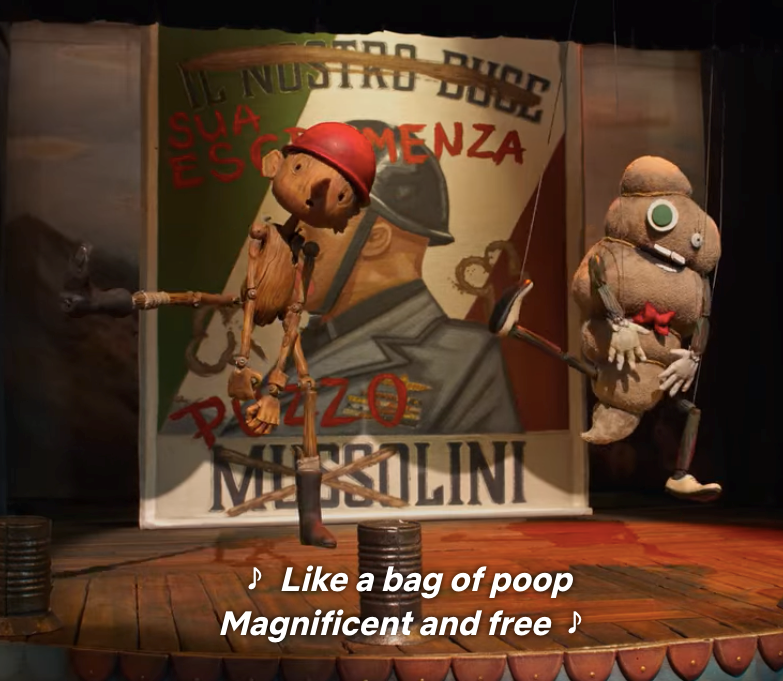

The “Fascist” part of the story really begins when Pinocchio goes on tour with a puppet show. This plot arc is very nimble and satirical, and is the film’s centerpiece. For the last stop on the tour, the show’s impresario, “Count Volpe,” is staging a special production for his “good friend” Il Duce. Volpe and his company take a steamship to Catania (Sicily), where the crowds cheer when Mussolini makes his appearance, driven up in an impossibly long red parade-car while the soundtrack cues up “Giovinezza, Giovinezza.”

I must say, this is a very squat, hideously caricatured Duce — but funny. It iscirca 1936, I suppose, given that a newspaper headline has shown him announcing We Win the War! Mussolini salutes the crowd and goes straight to the puppet theater. “I like-a puppets,” he tells the fawning puppet-master Volpe.

Today’s show is supposed to be a special command performance for Il Duce. However, Pinocchio has recently learned that the greedy, foxy boss Volpe is stealing all his earnings instead of sending them home to Geppetto. So in revenge he subverts the performance into a scatalogical burlesque of “Il Dulce” (as Pinocchio calls him). He dances with a turd-puppet and sings about how he, Mussolini, is full of urine, caca, and baby poop.

Mussolini, munching popcorn in the audience, says, “These puppets, I do not-a like,” and orders his bodyguard to shoot Pinocchio. Which the bodyguard does . . . but being a wooden puppet, Pinnochio cannot die. And as a result of this he is, logically enough, recruited into the Italian army.

This unlikely plot twist is the substitute for the famous “donkey transformation” in the original tale. Instead of traveling in a coach-and-four to Toyland (Pleasure Island in the Disney film), Pinocchio and his friend Candlewick get locked into the back of a military van and driven to an “elite” Fascist military academy, the inside of which looks rather like an avant-garde rock-climbing gym. And instead of being turned into donkeys (as naughty boys did in the original), the boys are herein being transformed into soldiers . . . ready to give their lives for the Fatherland!

Pinocchio’s friend Candlewick is accused of being a weakling by his martinet father, who apparently is this training facility’s commandant. Father hands son an automatic pistol and tells him to “Shoot the puppet!” (I detect an allusion to The Conformist, perhaps?) This crisis is quickly resolved, deus ex machina style, when enemy bombers suddenly appear overhead and bomb the school to smithereens. This second bombing scene is even more confusing than the first. Who is the enemy? Who was bombing Italy in the mid-1930s? I’ve read reviews that claim this is really supposed to be the 1939-45 war, but that doesn’t work, for a number of reasons I will forgo enumerating.

I’m obviously thinking too hard about this stuff. I understand the film is not attempting historical verisimilitude. I just wonder why certain new elements are invented and emphasized, while much of the original story and its cultural context is deprecated. I recently viewed the 1940 Disney version, which I mistakenly believed I had seen many years ago, though it turns out I hadn’t. And truly, it is quite as disjointed as this one, a concatenation of beautifully done set-pieces, even though it hews pretty closely to the (extremely uneven) original book. What it doesn’t do is treat the Collodi story as a sort of Mr. Potato Head text, where anything’s permissible so long as you’ve got a puppet in there called Pinocchio.

The promotional videos and press releases for this film keep reminding us of its renowned voice-artist cast. A particularly notable name is Cate Blanchett, who has done a couple of interviews for the film, and she also appears in an accompanying Netflix documentary in which cast and crew describe the film’s impossibly protracted development and production. As it turns out, Cate “plays” a manic monkey that mainly hisses and giggles. You wouldn’t recognize her in a million years.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “Paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

- Third, Paywall members have the ability to edit their comments.

- Fourth, Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected] [6]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[7]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[7]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.