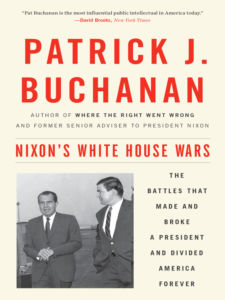

Pat Buchanan’s Nixon’s White House Wars

Posted By Jef Costello On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledPatrick J. Buchanan

Nixon’s White House Wars: The Battles that Made and Broke a President and Divided America Forever

New York: Crown Forum, 2017

It’s déjà vu all over again, folks. The more things change, the more they stay the same. This is one of the takeaways from this fascinating political memoir by Pat Buchanan, who worked in the Nixon White House as a strategist and speechwriter after serving Candidate Nixon on the campaign trail. It was Buchanan who coined the phrase “Silent Majority.” He helped strategize against George McGovern in the 1972 campaign, and he accompanied Nixon on his visit to China. Nixon’s White House Wars demonstrates that Buchanan had virtually unlimited access to the President and had a hand in almost everything that went on — except, thank God, Watergate. Buchanan’s only involvement there was after the fact: he tried to devise some way that Nixon could contain the scandal and keep his Presidency (ultimately, Buchanan took the position that Nixon had to resign).

When we look at the horror show that is today’s America, it’s easy to fall into the error of thinking that we are up against something new: the obvious bias of the press; the madness and violence of the American Left; the donothingism of the Republicans who fail their base again and again; the Republican establishment’s treatment of real conservatives and populists as “outsiders”; their repeated failure to seize the moral high ground from the Left; their pathetic quest to appeal to black voters and to win the approval of The New York Times, etc.

None of it is new. I was aware of this, and perhaps you were, too, but it is useful sometimes to get a vivid reminder, which Buchanan’s book certainly delivers. It is especially useful for the younger folk in our movement, who need to see that what we are witnessing now — in all the problems we face, cultural and political — is merely the outcome of trends set in motion long, long ago. Don’t misunderstand me: they weren’t set in motion during the Nixon years, but much earlier than that. (If you ask Heidegger, it began with Plato.) What is different today is merely the openness and intensity of the madness and corruption; the depths to which we’ve fallen, not the fall itself.

For example, those of middle age who dimly remember the Nixon years, as I do, often think the press used to be more objective. Buchanan’s book nicely demonstrates that this was not the case. The press just used to be more conscientious about creating the appearance of objectivity. That this is now deemed unnecessary, and that large numbers of people consuming mainstream journalism do not care, is one measure of how far we have fallen. To take another example, Watergate was a major scandal, involving genuine misdeeds by the President and his staff. But we have had worse scandals since then. Indeed, we are in the midst now of revelations about one: the collusion between the Democrats and social media to censor news and silence dissenters so as to deliver an election to the Democratic candidate. The difference between now and 1974, however, is that most of the public now seems to respond with a yawn. In ’74 a large portion of the electorate wanted Nixon prosecuted and were livid when Ford pardoned him.

[2]

[2]You can buy Jef Costello’s Heidegger in Chicago here [3]

When I recall the Nixon era, it feels like it was a golden age. This is because I was born in the mid-sixties (Buchanan was born in 1938). Again, the cultural rot is mostly a matter of degree. America in the Nixon era (1969-1974) really was a better America than what we have today — much better. My elementary school was entirely white. My neighborhood was all white. Save a few novelties like The Mod Squad and Sanford and Son, TV was all white, including the commercials. We played outdoors in the afternoons after school. No one was gender fluid. No drag queens dropped by the public library to read us stories. We were bullied by tubby, bellowing, whistle-blowing gym coaches and emerged the better for it.

It was possible to publicly oppose what we then called “women’s lib”; you could even be a “male chauvinist pig” and argue your case before Johnny Carson [4]. In general, people felt like they could speak their minds. They read books. No one cared what religion you were, so long as you had one. Virtually no one approved of interracial marriage, not even liberals. We could afford the luxury of “conservatives” who only talked about “limited government,” because no one thought we’d eventually be living in The Camp of the Saints. Most households only needed one breadwinner, and could afford to buy a house, an RV, take vacations, and send their kids to college. We also still built things.

My first political memories are of Richard Nixon. I remember the ’72 election, because I picked up a copy of Life magazine with George McGovern on the cover and asked my mother, “Who’s this?” “That’s a very, very, very bad man,” she said, “with lots of crazy ideas.” How right she was. McGovern was a batshit crazy liberal who lost in a landslide to Nixon — carrying only one state (Massachusetts) and losing his own (South Dakota). Conservatives thought the far Left had been decisively repudiated by the country and would never make a comeback. Oh, boy . . .

During the Nixon years my family lived in the Washington, DC area, and my father worked for the Defense Department. When Romania’s Nicolae Ceaușescu made a state visit to the United States, my father pulled strings and got us tickets to the White House. We stood waving on the White House lawn on a cold December day in 1973 as Nixon and Ceaușescu, just a few feet away from us, worked the crowd. The year before, when Nixon made his historic visit to China, I sent him a crayon drawing of himself (complete with ski nose) being received on the red carpet. I got a prefab thank you note back from the White House with Nixon’s printed signature on it. I think I still have it somewhere.

During the Nixon years I was the happiest I’ve ever been in my life. Of course, not much of this had to do with Nixon; it had to do with my being a little boy without a care in the world. By the time he resigned the Presidency on August 9, 1974, I had reached the ripe old age of eight. I had only the dimmest awareness of the country’s problems. My parents warned me about “hippies,” who they regarded (correctly) as sinister drug fiends intent on turning kids on to “dope.” Hippies terrified me more than clowns. I still remember the owner of our favorite restaurant ejecting two scraggly-haired, visibly dirty hippies from the premises because my mother and I were present, and this was “a family place.” And I remember the Watergate Hearings — only because they pre-empted my favorite afternoon TV shows (Doctor Who and The Avengers, running on the local PBS station). I have no recollections of Vietnam or the protests, but I do remember my parents griping about gas lines.

One thing that was worse in the Nixon era was domestic terrorism. This is something that has been almost entirely erased from public memory. But then Americans have short memories, anyway. Buchanan quotes one source saying that “between January 1, 1969 and April 15, 1970, more than 40,000 bombings, attempted bombings, and bomb threats were recorded in the United States” (p. 207). College campuses were particular centers of violence — which is not the impression one gets from all those rose-colored, nostalgic montages liberal documentarians produce showing campus “idealists” protesting to the tune of the Byrds’ “Turn! Turn! Turn [5]!” The same source states that

[i]n the 1969-70 school year, there were 1,792 demonstrations, 7,561 arrests, 8 people killed and 462 injured (299 of those injured were police). There were 247 cases of campus arson, and 282 attacks on ROTC facilities.

This brings us to an interesting observation. If you look for differences between then and now that are matters of kind and not merely of degree, you might cite the fact that we felt we were one country then, but that now we seem irrevocably divided. Buchanan, however, would reject this — and the statistics I’ve just given would form part of his case. In one passage early in the book, he reflects on how much had changed in America between the inaugurations of John F. Kennedy and Richard M. Nixon:

On that brutally cold day of January 20, 1961, I stood at 15th and Pennsylvania as the Kennedys in top hats and open limousines came by: Attorney General-designate Robert F. Kennedy, thirty-six, and his brother, forty-three, the youngest president ever elected. That was the America I grew up in, an America that was now gone. By January 20, 1969, we were in another country, no longer one nation and one people, but a land divided by war and race and culture and politics. [p. 24]

In other words, it was the sixties that divided America — and divided it “forever,” as the subtitle to Buchanan’s book states. Note the pessimism here: Buchanan clearly does not think that we are going to come together again.

Yet Nixon believed that he could heal these divisions. Nixon’s aim was to bring about world peace and domestic harmony. During the ’68 campaign, he had seen a little girl in Ohio holding up a sign that said “Bring Us Together.” He never forgot her. Fulfilling her wish, he promised the nation, would be the goal of his presidency. “Nixon’s dream,” Buchanan writes, “was to bring America and the world together, and enter history as the Peacemaker President.” And he adds: “The remarkable thing about Richard Nixon is that he truly believed this” (p. 23).

What Buchanan also makes clear, however, is that Nixon was no conservative. This will be shocking to those coming to the subject for the first time, since to this day Nixon is hated and reviled by the Left as a “Right-winger.” Indeed, the intensity of the Left’s hatred for Nixon at the time is hard to fathom, since in almost every way he wound up advancing the Left’s social agenda, often simply through failing to do anything to oppose it. (An older friend of mine has suggested that the root of their hatred was Nixon’s role in exposing the Communist spy Alger Hiss, who had been an official in the State Department.) Nixon was so not a conservative that he referred to conservatives in the third person. “What do they want now?” he would sometimes ask Buchanan in exasperation, referring to the conservative wing of the Republican party (p. 25).

It will be difficult for younger readers to grasp, but there was a time when “Republican” was not understood, in the popular imagination or in the self-conception of Republicans themselves, as synonymous with “conservative.” Our acronym “RINO” (Republican In Name Only) assumes this synonymousness — as if, for example, Mitt Romney isn’t a “real” Republican because he’s not a real conservative. But the “conservative movement” in the Party didn’t really get off the ground until the 1950s. And what “conservatism” largely meant was a limited government and anti-New Deal libertarianism, not the “paleo-conservatism” Buchanan himself would champion.

What gave birth to the conservative movement was the sharp leftward turn of the Democrats under Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Liberals were moving further Left, but the Republicans were merely an “establishment party” who opposed liberal social programs because they were “expensive,” and not fundamentally on moral or ideological grounds. The first great victory of the fledgling conservative movement was Barry Goldwater’s capture of the Republican nomination in 1964. Goldwater, who was half-Jewish, was basically proto-Reagan: fiscal conservatism, limited government, and self-reliance. His social views were so liberal he would not qualify as a conservative today, as we understand the term. Goldwater lost to Lyndon Johnson in a landslide following a dirty campaign [6] in which the Democrats sought to paint him as an “extremist” (a meaningless smear they coined especially for the occasion and have never tired of using).

However, the fact that a conservative (more or less) had been able to win the nomination meant that conservatives within the Party had clout. And their message seemed to resonate with Middle America, despite Goldwater’s loss. Nixon realized he had to ally himself with the conservatives, even though he was not one of them. This translated into exactly what we see today: Republican leadership wooing conservatives with promises and rhetoric, then delivering exactly nothing. The attitude about this in the Nixon White House was shockingly cynical. Buchanan reports that “the reflexive response to protests from the right was, ‘Don’t worry about the conservatives. They have nowhere else to go’” (p. 40).

“This was a White House whose senior aides looked on conservatives as outsiders,” Buchanan states (p. 45). To a great extent, Nixon’s staff and cabinet looked indistinguishable from LBJ’s. Buchanan quotes one conservative staffer’s diary: “As I watch our Cabinet in action, I wonder more & more whether or how they differ from the LBJ people. They push for their departments, care not about money, rely on LBJ’s people and talk like them” (p. 27). The result of this was not just the absence of conservatives, but the presence of individuals fiercely opposed to conservative policies. Buchanan reports that “there was not an ideological conservative among Nixon’s West Wing assistants or cabinet officers” (pp. 39-40).

Part of the reason for this was that there simply weren’t enough conservatives with government experience who could fill positions in the Nixon administration. Buchanan writes:

Though our movement had exhibited real political power in capturing the nomination for Barry Goldwater . . . and though we were veterans of the victorious presidential campaign, few of us had served in the executive branch. We lacked titles, resumes, credentials. The conservative movement, since infancy, had been an insurgency, a revolutionary movement, never part of any ruling coalition. Our pool of experienced public servants who could seamlessly move into top positions was minuscule compared to that of the Liberal Democrats who had dominated the capital’s politics since FDR arrived in 1933. [p. 40]

The results of Nixon’s failure to oust liberals from government departments were entirely predictable. For instance, the State Department actively opposed many of Nixon’s foreign policy endeavors. Buchanan writes:

The returns from Nixon’s failure to staff his government with loyalists who would follow his lead and carry out his policies were now in. We had failed to clean house at State as we promised. Now State had gone back to business as usual and was no longer fearful of White House displeasure or discipline. The chance to seize control of and to redirect the government of the United States had passed us by. It would not come again. [p. 57]

The situation is eerily similar to what Trump faced. Trump’s populist, “America First” conservatism was an entirely new brand — much further to the Right than the philosophies of Goldwater and Reagan. There simply weren’t enough likeminded individuals capable of moving into top-level positions within the government, and so Trump had to rely on Republican Party stalwarts, most of whom later turned on him. The internal opposition to Nixon was, it must be said, not nearly as ferocious as that faced by Trump. Much of the opposition to Trump had to do with snobbery and classism — the view that Trump was not just an outsider, but a low-class, nouveau riche yob from Queens. Buchanan reports that “the liberals and moderates on the [White House] staff recoiled at the idea of belonging to a Republican Party whose leaders like Rockefeller, Javits, Lindsay, Hatfield, [George] Romney, Percy and Scranton had been displaced by the Goldwaters, Reagans, Thurmonds, and Agnews” (p. 146).

Then as now, the Republican Party establishment viewed real populist conservatives as upstarts, counter-jumpers, and gate-crashers who couldn’t be counted on to behave properly if admitted into the club. Goldwater, Reagan, et al. had all been successful in spite of the Party establishment. It’s a pattern all too familiar to us: The Party only handed the nomination to Trump in 2016 because they had no choice. He had swept the primaries and was clearly the favorite of Republican voters. Had they chosen Jeb Bush instead, the base would have stayed home on election day out of sheer disgust. So, the establishment held their noses and went with Trump, and counted on being able to control him if he won.

[7]

[7]You can buy Jef Costello’s The Importance of James Bond here [8]

Nixon, by contrast, was a creature of the establishment: A graduate of Duke Law School, he had served in both the House and the Senate before becoming Vice President to Dwight Eisenhower. Before his great comeback in ’68 (which was, indeed, remarkable), he had already been the Republican Presidential nominee in ’60, losing to John F. Kennedy (due, in large measure, to massive voter fraud perpetrated by Kennedy’s dad, Joe). While Nixon was no conservative, this did not mean that he was a committed liberal. Though he may have possessed some sincere idealism about “bringing us together,” he seems to have had no firm ideological convictions at all.

When one conservative aide complained to White House Counsel John Ehrlichman that a proposed welfare program was antithetical to the President’s philosophy, Ehrlichman replied, “Don’t you realize the President doesn’t have a philosophy?” (p. 27). The same aide wrote in his diary, “have I misjudged Nixon? Does he have real convictions? I thought so when I first entered the administration. . . . But my doubts on the score have been multiplying in recent weeks and months” (p. 206). Perhaps most damning of all, Buchanan states that “a defining mark of our White House was a sleepless search to accommodate every side of every argument” (p. 139).

Nixon comes off more as a “people pleaser” than as the ogre the Left has portrayed him as. Conservatives believed that, if elected, Nixon would put the kabosh on LBJ’s vast array of welfare programs known as “the Great Society.” And Nixon, of course, had signaled to conservatives that he would do just that. But — surprise! — it was not to be. Buchanan writes, “No real effort was made by the President, his Cabinet, or his White House staff to roll back the Great Society. With a few rare exceptions, LBJ’s programs were to be preserved and fully funded” (pp. 24-25).

This was also true of “busing”: the forced integration of public schools by busing black kids into white neighborhoods and (to the best of my recollection) vice versa. Remarkably, Nixon and most of his staff were in agreement that busing was immoral, but under Nixon it continued. Part of the reason for all these failures to act was that Nixon actually believed that not rolling back the social engineering of the sixties would help him curry the favor of Democrats and their allies in the press. This now seems shockingly naïve, but Buchanan confirms it. To give still another example, then as now Republicans argued that the taxpayer-funded PBS exhibited gross Left-wing bias and ought to be defunded. But instead of that, funding for National Public Radio actually increased during the Nixon years.

Then as now, establishment Republicans failed to see who their real base was, or to be attuned to the mood and desires of that base. Instead of recognizing that they needed to work for the interests of the “Great Silent Majority” to whom Nixon had appealed in ’68, a proposal put together by Ehrlichman argued that the Party should appeal to “black, Jewish, and Hispanic voters” (p. 144). (Sound familiar?) Buchanan and other conservatives made the case for uniting the Nixon center-Right coalition of 1968 to the millions of conservative southern Protestants and conservative northern Catholics who had supported segregationist George Wallace in the same year (Wallace ran a third-party campaign). This proposal was rejected out of hand. Those voters were just too déclassé.

Predictably, there was a good bit of sucking up to blacks in the Nixon White House. Buchanan describes a disastrous meeting between Nixon and Rev. Ralph Abernathy, who had succeeded Martin Luther King as leader of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Nixon approached the meeting in a spirit of good will, but Abernathy showed up with a list of demands and proceeded to berate Nixon. The President endured this abuse for an hour, then politely ended the meeting. Privately, Nixon expressed that he was “Pretty fed up with blacks and their hopeless attitude” (p. 38).

Yet, it’s a notorious fact that it was under Nixon that Affirmative Action really got going. Buchanan’s comments on this shameful practice and its disastrous consequences are worth quoting at length:

From Nixon to today, affirmative action, though voted down in nearly every state where it has been put on a ballot, has been applied to the hiring and promotion policies of universities, businesses, unions, and government. As the beneficiaries have expanded to include women, Hispanics, Native Americans, and the handicapped, the only minority left against whom it is legal, and commendable, to discriminate, is that of white males. During Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign, the media awoke to discover that America’s white working class had been in the economic doldrums for decades, and was in social decline, with suicides, alcoholism, spousal abuse, and family breakups soaring. Moreover, that working class wanted to overthrow the establishment. What did the elites expect, after their half century of systematic discrimination against white males, and, by extension, their wives and kids? [p. 86]

As I write this, now almost 50 years after the Nixon administration, the Supreme Court seems as if it may be about to strike down Affirmative Action. Earlier this year, of course, it overturned Roe v. Wade. In case you don’t know, it might interest you that the majority decision in the 1973 Roe case was written by Nixon appointee Judge Harry Blackmun. As the saying goes, with friends like these, who needs enemies? After describing a debacle in which John Ehrlichman appointed a black radical Leftist to sit on a presidential “Commission on Campus Violence,” a Leftist who immediately turned on the administration that had given him a platform, Buchanan wrote an internal memo speculating that “there must be some inherent suicidal tendency or death wish” in Republicans (p. 176). Amen.

One bright spot in the Nixon White House was Vice President Spiro Agnew. Nixon used Agnew as an attack dog, and as a mouthpiece for the conservative ideas to which he himself gave such tepid support. Buchanan worked with Agnew on a series of speeches in which the Vice President went on the attack against the bias of the liberal press. As I mentioned earlier, one valuable feature of Nixon’s White House Wars is that it makes plain that this bias goes way back. Those in our movement unable to remember a time before the Internet rightly decry attempts by the establishment to control the flow of information through, for example, the censorship of social media. But they really don’t know how good they’ve got it. In the Nixon years, all you had was ABC, CBS, and NBC, as well as newspapers like The New York Times and Washington Post, all of which toed the exact same left-of-center line. There was no “alternative press,” no independent journalists with a platform, no bloggers. If you wanted to get your message out, the best you could do was assemble a mailing list and start sending out a mimeographed newsletter.

Agnew called out the bias of the liberal press — and, in Buchanan’s view, he made a lasting contribution in forever damaging the prestige of that press in the eyes of the public. Then as now, the press responded to such attacks by saying that the Republicans were fascists threatening their First Amendment rights. These fat cats tried to position themselves as martyrs, in other words. Buchanan writes:

We could not muzzle them. Nor had we a desire to do so. But we could and did use our freedom of speech to strip them of their bogus claims to objectivity and to expose them as every bit as ideological and political as we were we. In the 1960s, the press had sailed serenely under a flag of neutrality, claiming immunity from the kind of attacks that they themselves routinely delivered for their causes and comrades. After [Agnew’s attack] their credibility would never be restored. They would come to be seen as having axes to grind like everyone else. Their immunity came to an end, but their power endured. [p. 89]

Buchanan’s portrayal of Agnew is wholly positive. He comes across as a likeable figure — a real fighter who might have become a real conservative President, if, in 1973, he had not been forced to resign the Vice Presidency in disgrace over a financial scandal. Agnew, scripted by Buchanan, also fired some of the first shots in what Buchanan would later come to call the “culture wars.” Agnew’s speeches, writes Buchanan,

addressed the revolution in thought that had converted the elites who commanded the heights of the culture — the universities, the media, the arts, the churches. What had taken place was a “revolution within the form.” Outwardly, our institutions appeared the same, but inwardly their orientation was wholly new. Protestant churches had cast aside preaching and teaching the Gospel of salvation to embrace a gospel of social revolution. Agnew lacerated the National Council of Churches for having “cast morality and theology aside as not ‘relevant’ and set as its goal on earth the recognition of Red China and the preservation of the Florida alligator.” [p. 85]

The reference to the “recognition of Red China” is ironic, given that it is widely held that one of Nixon’s real accomplishments was the normalizing of relations with that murderous regime. Nixon and his entourage, including Buchanan, made a state visit to China in February 1972. Buchanan describes Shanghai as grim. Recalling his visit to the USSR earlier in the year, he said to a colleague, “This place makes Moscow look like Mardi Gras” (p. 240). By contrast, the mood of Nixon and the American delegation was positively manic. Nixon, seeing himself as the great peacemaker, no doubt viewed this as his big moment in history. At a gala dinner, Buchanan relates, “Nixon seemed to be going overboard with his toasts” (p. 241). William F. Buckley, who was along for the ride, said he would not have been surprised if Nixon had risen to toast Alger Hiss.

[9]

[9]You can buy Greg Johnson’s The Year America Died here. [10]

While everyone else seemed to be having great fun, Buchanan was having grave doubts. He wondered to himself, “are we any different than that American party that traveled to Yalta, where FDR and Churchill, who was ‘downing buckets of champagne,’ according to Lord Moran, capitulated to Stalin’s demands for all of Eastern Europe?” (p. 241). Indeed, there is a kind of insanity about this whole escapade. How could we expect American boys to fight and die opposing Communism in Vietnam when their leaders were simultaneously cozying up to the deadliest Communist regime that ever was?

And hindsight makes the whole thing seem like a catastrophic mistake, as the normalization of relations with China soon opened American markets to cheap Chinese goods, and helped the Chinese overtake our own country economically — and possibly even one day militarily. Near the end of his life, Nixon said to journalist Bill Safire, “We may have created a Frankenstein” (p. 248). Buchanan was so disgusted by the administration’s performance in China — which effectively included throwing Taiwan under the bus — that he contemplated resigning. He changed his mind and remained in the White House until the early days of the Ford Administration.

I doubt that what I have said so far will leave the reader with a positive impression of Richard Nixon. But this is one reason to read Buchanan’s book, and not take my word for things. For the portrait of Nixon that emerges is one of a complex individual who, despite all his failings, inspired fierce loyalty in his associates. Indeed, it is obvious that Buchanan loved Nixon. He describes himself at one point, a few months after Nixon’s resignation, almost breaking down in tears when he heard a false news report that Nixon had died (in fact he had had an attack of phlebitis and had almost died). Just exactly how Nixon was able to command such loyalty is difficult to say. Part of the reason is that he was loyal himself — sticking by people and rewarding people who stuck by him. He was open to criticism when it came from allies. And he gave his subalterns plenty of positive reinforcement. Buchanan clearly relishes reporting every note he ever got from Nixon commending him on a job well done.

Nixon was not the cold, emotionally-repressed fish the liberal media portrayed him as. Indeed, he was a passionate man. Buchanan contrasts Nixon’s temperament to Reagan’s, for whom he worked as White House Communications Director. Reagan got angry over things, but he quickly calmed down. By contrast, Nixon brooded — especially when attacked by the liberal press. As Buchanan puts it:

Every President is affected by what is written and said about him and reacts to severe or savage criticism. But Nixon was more sensitive to such attacks and wounded by them than any figure I have known in fifty years around national politics. The establishment disparaged and despised him for reasons I could not comprehend, given his centrist politics and even liberal policies, remarkable abilities, and extraordinary accomplishments. Yet, still, Nixon avidly sought out and welcomed their approbation, and was stung by their attacks. [p. 53]

When hit by his critics, Nixon would often call Buchanan and other aids, sometimes at all hours of the night, and request that they plan some sort of counterattack. Most of the time, Buchanan reports, he would call back the next day, after he had simmered down, and tell them to forget about it. One Nixon insider later stated that “Watergate happened when some damn fool came out of the Oval Office — and did exactly what the President told him to do” (p. 52).

Ah, yes, Watergate. In 1968, Gallup had Nixon’s approval at 68%, and he was the most admired man in America. By August of 1974, he was forced to resign in disgrace or face impeachment and possible removal from office. The details of Watergate are too well-known for me to rehearse them here — and if you don’t know the details, Buchanan’s book will provide you with them. Suffice it to say that the Watergate break-in was never Nixon’s idea. What got him in trouble was the decision to actively cover it up, or to cover up White House involvement. Arguably, what did Nixon in was his loyalty: In part, he was acting to protect the men who had so loyally served him. These included the infamous G. Gordon Liddy, who actually said he would kill for Nixon.

The story of Nixon’s fall is genuinely tragic and it is impossible not to feel for this man, who Buchanan manages to portray so vividly. Buchanan himself also shines through in this text. In part, he succeeds in making clear, for the historical record, just how much influence he had in the Nixon administration — though it is sad that his advice was not followed more often! Buchanan amply demonstrates here that he is a brilliant political strategist. I have always admired the man, whom I refer to among friends simply as “Pat.” I have read every one of his columns at least for the last ten or 15 years. Aside from a few areas of blindness, he is a wise conservative voice and I have learned a great deal from him. He is also clearly much more “conservative” (hint, hint) than he lets on.

Nixon’s White House Wars is also an exciting book — seldom have I read a political memoir that was such a “page turner.” I envy Buchanan. I halfway wish I could have been there. I halfway wish I had been taken under the wing of some political figure, and worked at the very top level of government as speechwriter and advisor, as Buchanan did. It must have been extraordinarily exciting. Of course, one of the things Buchanan’s book makes clear is that ultimately his experience with Nixon was disappointing. Buchanan spent years working at the side of a man he loved, who managed to fail the nation in myriad ways — not least by his “centrist politics” and “liberal policies.” And it is depressing to see how little has changed — how American politics is more or less “the eternal recurrence of the same.”

If anything, Nixon’s White House Wars has strengthened my growing conviction that nothing can be accomplished by working within the present political system.

* * *

Like all journals of dissident ideas, Counter-Currents depends on the support of readers like you. Help us compete with the censors of the Left and the violent accelerationists of the Right with a donation today. (The easiest way to help is with an e-check donation. All you need is your checkbook.)

For other ways to donate, click here [11].