Frank Salter’s On Genetic Interests

Posted By Spencer J. Quinn On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledThe members of an ethnic group who cease striving to preserve their ethnic genetic interest have their inclusive fitness — their adaptiveness — reduced to the individual fitness of children and close family. They are, in effect, leaving their ethnic genetic capital to chance — the vagaries of nature and the good-will of competing groups. — Frank Salter

It may seem ironic that one of the most canonical pro-white and pro-white nationalist works ever written hardly mentions the white race at all. But it really isn’t ironic. Since White Nationalism is moral and perfectly natural, based on quantifiable genetic data, and a subcategory of universal ethnic nationalism, any work providing its biological, evolutionary, and theoretical underpinnings need not mention a specific race. What applies to whites applies to all races and ethnicities that aspire to nationalism.

Frank Salter’s 2003 classic On Genetic Interests posits that all people have genetic interests, which Salter defines as “the number of copies of an individual’s distinctive genes.” During the twentieth century, most theorists focused on how genetic interests apply to family and extended kin. Since siblings and cousins share genes at a greater frequency than with random non-family members, it follows that an individual express loyalty to family more than with non-family. This loyalty often takes the form of altruism. In the most extreme cases it denotes how the sacrifice of one’s life to save another’s can make the family or clan more evolutionarily fit — depending on genetic closeness and the number of individuals being saved.

[2]

[2]You can buy Spencer Quinn’s novel White Like You here [3].

Ethologist William Hamilton coined the term “inclusive fitness” in 1964 to describe how an individual can affect the genetic interests of a family or clan which shares certain gene frequencies. Salter’s innovation was to expand inclusive fitness to include ethnic groups and races — which makes sense given that by 2003 mass migration into the West had become impossible to ignore. He views an ethnic group (or ethny) as a greatly extended family, and a race as a collection of closely related ethnies. Races also have unique gene frequencies, just as ethnies and families do, which means that members of races have a natural — and indeed, moral — obligation to protect their genetic interests.

The ramifications of such an idea are, of course, enormous. Salter proposes nothing less than a lucid political system which incorporates genetic continuity and adaptive behavior. These are ends in and of themselves, since we value life for its own sake and do not need to offer proofs as to why we wish to live and procreate. Salter describes in Darwinian terms a formidable obstacle preventing the fulfillment of genetic interests: competition from what he calls “proximate interests,” such as wealth and status, which also motivate human behavior — sometimes to increase fitness, and sometimes not.

The main problem is the slowness of natural selection compared to the rapidity of technological and social change since the Neolithic. The inertia of adaptations can cause them to continue to promote proximate interests that no longer serve fitness.

Drawing on J. Philippe Rushton’s Genetic Similarity Theory, Richard Dawkins’ concept of populations behaving as “superorganisms,” Edward O. Wilson’s theory of micro-evolution, and other prominent sociobiological ideas, Salter lays out a metric to determine genetic relatedness and uses gene mapping to mathematically calculate how behavior impacts genetic interest (or what he calls “an individual’s familial genetic stake”). Values in his equations include genetic relatedness, group size, and the genetic difference between competing races or ethnies — all of which can be quantified.

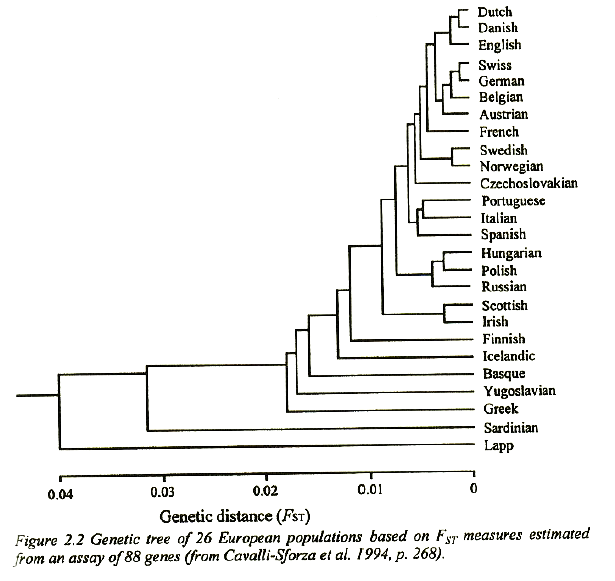

Salter provides the following graph to demonstrate genetic relatedness among European populations.[1] [4]

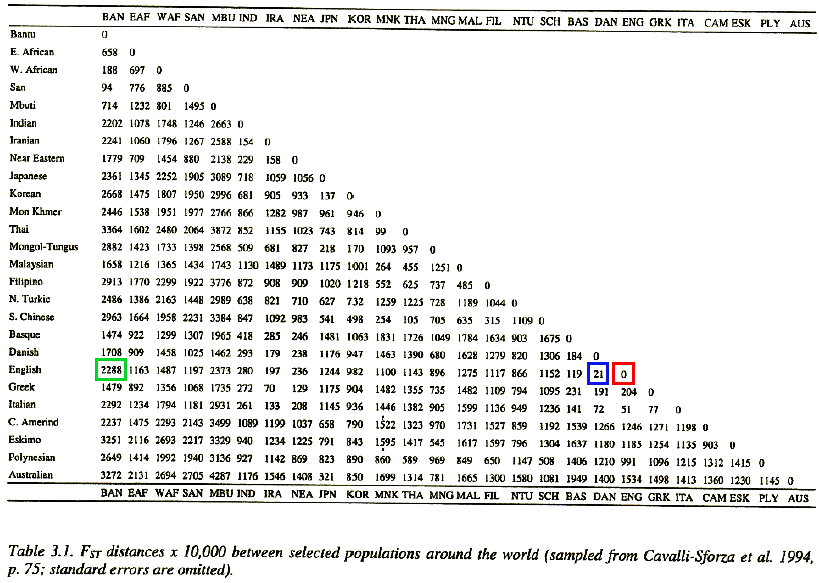

He then provides the following table to demonstrate genetic relatedness among global populations.

Note that the numbers above divided by 10,000 correspond to the X-axis of the previous graph. Thus, the genetic distance between the English (red square) and the Danes (blue square) is a mere 0.0021, while the genetic difference between the English and the Bantus (green square) is a whopping 0.2288. We would have to zoom out quite a bit to map that distinction on the above graph.

Salter describes how this would play out in real life using mathematical formulae developed by Henry Harpending in his 1979 American Naturalist essay “The Population Genetics of Interactions.” If 100 ethnic Danes replace 100 ethnic English in England, according to DNA data 1.67 English children’s worth of unique genetic data would be lost forever. This tiny figure is a function of the genetic similarity between the English and Danish, as well as the small number of individuals being replaced. On the other hand, replacing 100 English with 100 Bantus would lose about 108.5 English children’s worth of genetic interest. This is because English and Bantu DNA are that different.[2] [7]

Although Salter readily admits that Bantu genetic interests would be equally reduced if 100 English were to replace 100 Bantus in Africa, the closest he comes to drawing qualitative conclusions is to point out that genetic interests include all heritable traits, not all of which are equally desirable:

Since adaptive ethnic altruism is homologous with extended kin selection, one is also defending all group qualities with high heritability, such as cognitive profile, personality, and physiognomy. Those differences are moderate within geographical races, but can be large between races. Moreover, there is growing evidence that differences in traits such as IQ have large effects on standard of living, both between individuals and ethnies within one society and between societies. So even if our critic rejects the value of ethnic kinship in its own right, he might embrace it if he cares about preserving for future generations the proximate values linked to it, such as culture and wealth.[3] [8]

He also speaks out eloquently in favor of chauvinism:

A pronounced group identity usually results in group pride, the believe that one’s group is in some way distinguished. Notions of ethnic superiority are used as ideological weapons in inter-group competition, to bolster the ingroup’s confidence and break the spirit of other groups, in effect, claiming precedence for the assertive party. Chauvinism thus has its functions, and might be considered morally superior to arrows and hatchets as a means for conducting intergroup competition, but it should never be confused for truth.

Salter spends a lot of time on the problem of free riders. Such people benefit from misguided altruism and do not increase the ethny’s fitness. They can be of the same ethny as the altruist or an outgroup member. The free rider problem is reduced within a single ethny, since “members should be more willing to invest in the group the more dense the ties of kinship within it.” On the other hand, when outgroup members benefit from altruism, they have the added bonus of making their ethny fitter at the expense of the altruist’s. Thus, multiracial societies become rife with free riders, since free-riderism is a low-cost, high-reward form of ethnic and racial competition.

[9]

[9]You can buy Spencer J. Quinn’s novel Charity’s Blade here. [10]

One brilliant aspect of On Genetic Interests is Salter’s use of “fitness portfolios.” In these chapters, Salter describes strategies that ethnic groups can use to increase their own fitness at the expense of the fitness of competing groups. These include government-administered social controls, minority coalitions, separation/secession, and encouraging maladaptive behavior on the part of competing groups. Salter insists that all ethnies must be vigilant while defending their genetic interests unless they wish to face the eventual loss of their genetic uniqueness.

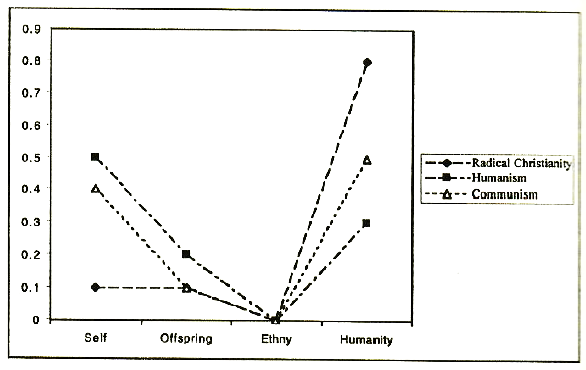

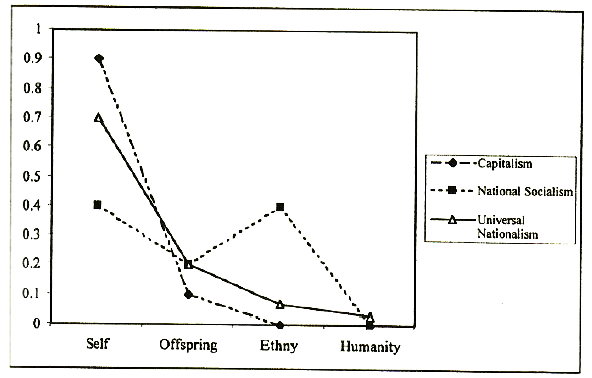

Various ideologies and religions provide strategies for this, and Salter compares them in the following fitness portfolios. These graphs map the ideal or intended expenditure towards a particular strategy, and are therefore impressionistic and not based on real data. They demonstrate how strategies differ when it comes to defending a person’s various interests — which can be separated into four broad categories: Self, Offspring, Ethny, and Humanity. All energy expended occurs after a person’s basic needs are met and adds up to a value of 1 along the Y-axis below:

One can quibble about whether the Nazis really promoted ethnic altruism over familial altruism to this degree, or whether capitalism prescribes such a vast differential between self and offspring, but the usefulness of the fitness portfolio should be clear. Any ideology or social, political, or economic system can have a fitness portfolio which places its intended behaviors in stark contrast with those of others. The fitness portfolio provides fertile ground for thought experiments, which could perhaps allow adherents of a particular system to reach a consensus more readily.

Salter prefers “universal nationalism” (in the second graph above) due to its balanced portfolio, and dedicates a chapter to its pros and cons. It would make sense that White Nationalism, which is a subset of universal nationalism, resembles that system most closely. But how closely? Perhaps timing would make a difference. How would White Nationalism 1.0 today, suppressed and demonized as it is, differ from White Nationalism 2.0 in a bona fide future white ethnostate?

Here is my stab at an answer. Feel free to argue in the comments:

Salters ends On Genetic Interests with a fascinating discussion of the ethics and workability of a biologically-informed political philosophy. He delves into utilitarianism as developed by Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill, and then proposes adaptiveness as utility. He suggests that Darwinian fitness for the greatest number should replace happiness, pleasure, or wealth for the greatest number as the end goal. He argues that with classic utilitarianism, it is possible to have too much of a good thing. For example, a man with too many wives or too much wealth may enjoy a monopoly which might not impact the majority’s happiness in the short term, but could impact the population’s fitness in the long term. Lacking a survival ethic, utilitarianism suffers from an arbitrariness regarding what is considered good. But adaptive utility does not have this problem, since it is impossible to be too well adapted.

Salter fully concedes that his ideas are still very fresh, and that much more research and study must be performed before adaptive utility as a biologically-based political system can graduate to the exalted status of philosophy. In the meantime, we can review the quote from the beginning of this review and realize that with On Genetic Interests Frank Salter has done what few writers have been able to do: provide a coherent language and scientific mode of thought which nationalists everywhere can use to protect their genetic interests and fight for their very survival.

* * *

Like all journals of dissident ideas, Counter-Currents depends on the support of readers like you. Help us compete with the censors of the Left and the violent accelerationists of the Right with a donation today. (The easiest way to help is with an e-check donation. All you need is your checkbook.)

For other ways to donate, click here [14].

Notes

[1] [15] Salter explicitly promotes European distinctiveness by debunking the theory of the relatively recent settlement of Europe by Near Eastern tribes 8,000 years ago, and also the theory that the European ethnies are so mixed that their ethnic kinship is effectively zero. According to Salter, Europeans “are a largely autochthonous people who can trace their origins back for several tens of thousands of years to a small number of founding tribes.”

[2] [16] Despite the term not yet having been coined back in 2003, Salter presciently discusses the Great Replacement in On Genetic Interests:

Thus a fundamental, though by no means unique, threat to ethnic genetic interests is loss of the ethnic monopoly of a territory. The great advantage of this monopoly is that is facilitates continuity of the tribe’s gene pool by boosting the group’s ability to defend against mass immigration, whether violent or peaceful. . . . A decimated, defeated, or impoverished population has a chance to recover if it retains control of its territory. But a large-scale influx of genetically distant immigrants has the potential permanently to reduce the genetic interest of the original population.

I expressed a similar idea in my essays “Democrats Are the Real Racists (and Blacks Don’t Care)” [17] and “If I Were Black I’d Vote Democrat.” [18] American blacks consistently vote against their economic interests and tolerate much criminal behavior among their own because this is the best way to ensure territory for their ethny. Essentially, the near-constant state of poverty, violence, and disarray in black neighborhoods keep the non-blacks out and protect black genetic interests.

[3] [19] Salter’s sources for this passage are texts which should be familiar to most Counter-Currents readers: Herrnstein and Murray’s The Bell Curve (1994), Rushton’s Race, Evolution, and Behavior (1995), and Lynn and Vanhanen’s IQ and the Wealth of Nations (2002). More recent texts which solidify the findings in these books are Vanhanen’s The Limits of Democratization (2009) (my review here [20]), A Troublesome Inheritance (2014) by Nicholas Wade (discussed at length here [21]), The Neuroscience of Intelligence (2017) (my review here [22]), and Stephen Sanderson’s Race and Evolution (2022) (my review here [23]).