Johnny Whistletrigger Music of the Civil War in Missouri

Posted By Steven Clark On In North American New Right“I’ve just got a new record of Civil War music,” my brother recently bragged over the telephone.

He wanted some snappy tunes to listen to, and mentioned that the Nazi marches he is so fond of have been banned from YouTube. “I’ve discovered Italian Fascist marches,” he said. “They’re very melodic and . . . so operatic.” He referred to a long-ago record cover. “They’re so warm.”

“Perhaps smarmy,” I volunteered. Those I’ve listened to have that muzak sound that is absent in the Third Reich’s offerings.

“Well,” he said, “at least I can listen to them. But I’m getting into the Civil War music.”

I assumed the Civil War music he listened to was a collection of brass band marches — the usual panoply of regimental tunes, polkas, waltzes, and so on. Maybe some songs thrown in, à la Stephen Collins Foster and the usual rah-rah stuff like “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” “Marching Through Georgia,” and “Dixie” . . . or maybe not, since Confederates are now proscribed.

I like the music of the era myself, but I go in for a more period sound, such as “The Union Forever” by D. C. Hall’s Quadrille Band. I remember the group in Boston, and I went to concerts and balls where they performed. With a strong tenor in Kevin McDermott, the group offers a lively, period feel to the usual tunes, both martial and sentimental. The dance pieces, such as the Columbia Quadrilles, are also enjoyable because I actually danced to this music at Civil War balls; the only sound missing is the swish of ladies’ satin and taffeta gowns as I danced near them on the floor.

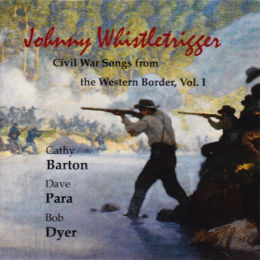

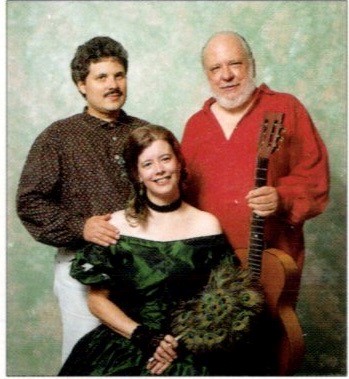

But the Civil War in Missouri isn’t quite as nostalgic. Unlike the rest of the country, it was host to a fierce guerrilla war not easily forgotten at war’s end. Indeed, in T. J. Stiles’ Jesse James: The Last Confederate (reviewed here [3]), Stiles argues that the war’s divisions were an active feature of both post-war politics and Jesse’s unsavory career in crime — or retribution. It depends on which side of the fence you squatted. While I was writing my review I returned to my CD collection to visit Johnny Whistletrigger and Rebel in the Woods, remarkable sets of Civil War music related to the war in Missouri that was recorded by the trio of Dave Para, Kathy Barton, and Bob Dyer. They offer a heartfelt and thoughtful retrospective on the period as shown in their music, which was all meticulously researched, and more than once it came into touch with their own families that had been affected by the war.

All three of them lived in Boonville, on the Missouri River, a historic town in its own right. Thespian Hall, the town theater where they often performed, is considered to be the oldest operating theater west of the Mississippi, and its façade is marked by bullet holes from not only one, but two battles fought that were fought in Boonville during the Civil War. Thus, they have a unique historical sense that made them naturals for performing this music.

An earlier recording from 1982, The Ballad of the Boonslick, showed their ability and love for making and preserving historical music from Missouri. The Boonslick refers to the area in central Missouri where there are salt licks once claimed by Daniel Boone’s sons.

This collection of fiddle tunes and songs offers moments of poignancy where older tunes are mixed with modern lyrics and introspections regarding the past and present. In “The Dry Waltz,”composed by Bob Dyer and sung in Cathy’s clear, high voice, love, loss, and the problems of drought intermingle:

I don’t know how long it’s been since we’ve had rain.

And when the love no longer flows,

And the cracks begin to show

I’ll understand, but I just can’t stand the pain.

Dyer expanded upon loss and the caprices of nature in the recording’s signature song, “The Ballad of the Boonslick.” He offers a roll call of the settlers who first came to Missouri and sings of their labor and hopes, and describes how one of their towns, Franklin, “crumbled into the stream” during one of the river’s floods:

They were the pioneers, came here from far and near.

But the river had a will of its own,

And the loss of their town and homes

Was the price that they paid.

Although Franklin crumbled, Boonville took its place and rose to strength in the steamboat days, but both the river and humans are capricious, especially in Boonville’s case:

She was a boom town city on the bluffs above the river

Queen of the steamboat trade

But then the bloody war of the brothers came,

And after she was never the same.

This song echoes Stiles’ description of Missouri’s vibrant self-contained society and economy during the antebellum years, and is a perfect prelude to Johnny Whistletrigger.

The album is less a collection of songs and instrumental pieces than it is a musical journey through the roiling ambiguousness of the Civil War in Missouri. There were no great, fateful battles compared to the southern or eastern theaters of the war, but the passions of that war and the region are captured here, and it is to the credit of the performances and musical synthesis of Para, Barton, and Dyer that the songs are remade in a contemporary way that is meaningful to us today — certainly in Missouri, but also for America.

It begins with “Marmaduke’s Hornpipe,” a rousing fiddle tune named for John Sappington Marmaduke, a Confederate general who became a post-Reconstruction Missouri Governor, capturing the down-home flavor of the border areas. Next, they move to the abolitionist world, where Dyer recites — not sings — “Marais des Cygne,” recalling the 1858 massacre of free-state farmers in Kansas by Missourians:

A stain that shall never

Bleach out in the sun.

The 1858 poem’s religious overtones, which speaks about how “The crown of the harvest / Is life out of death,” leads into an abolitionist hymn and a song about emigrants from Kansas, anti-slavery pioneers whom Missourians saw as a threat to their enclosed, vibrant society. The hymn is sung in shape-note style, also called sacred harp — a style of music very folkish and religious that Dave and Carthy were quite fond of. Here it is used for a Northern theme, but sacred harp was (and is) very popular in the South.

[4]

[4]You can buy Tito Perdue’s The Philatelist here [5].

St. Louis was contested by both sides in the war for its arsenal, and this is depicted in “The Invasion of Camp Jackson,” sung in a semi-comic, sarcastic secessionist’s viewpoint of troops squashing southern attempts to seize the arsenal, leading to subsequent riots where Union troops opened fire on a crowd (or mob; take your pick), and killed two dozen people.

The leader of Union forces was General Franz Sigel, who led a German community that was pro-Union, abolitionist, and crucial to keeping Missouri in the United States. He gets a grand march, ,ut also the grotesque “I Goes to Fight Mit Sigel,” another secessionist squib that mocks the Germans to the tune “The Girl I Left Behind Me”:

But now I march mit musket out to safe dot Yankee Eagle,

Dey dress me up in soldier’s clothes to go and fight mit Sigel

I especially enjoy this song, since it was published in the Missouri history book I studied in high school.

“Johnny Whistletrigger” is the recording’s centerpiece, but it is not exactly a Civil War song, even though the fiddle tune was known then. Dyer recounts the life of John D. Hurt, a Boonville man known by this nickname, and the song is of the type about the robber, rascal, or peasant on the run, the underdog always one step ahead of the man:

He made it to Boonville and looked up his wife.

But early next mornin’ at the break of day

Johnny woke up when he heard his wife say . . .

Run, Johnny Whistletrigger, Federals’ll get you.

Run, Johnny Whistletrigger, better get away.

It’s a neat introduction to what becomes a major theme of the collection: the bushwhackers, guerrillas who fought and harassed the Union forces and their supporters. They were men who, if forced to live on the sly like Johnny Whistletrigger, were no less determined to keep fighting for Missouri’s freedom.

The chief of these bands was William Quantrill. Quantrill was an enigmatic figure in the border war. Originally a schoolteacher in Kansas who lived amiably among the abolitionists, just after the troubles started he quickly changed sides and became a major thorn in the Union’s side in Kansas and Missouri.

The CD includes a spoken address that was originally given by Sterling Price in 1861, appealing for volunteers. He needed 50,000 and got 5,000. Part of this address was quoted in my review of Stiles’ book. The bushwhackers are a major theme in these recordings. After the Confederate defeat at Pea Ridge in early 1862 (noted in the a cappella “Battle of Pea Ridge”), Union harassment of “Secesh” folk angered many people. In addition to this, Quantrill’s raids caused many young men to “go to the Quantrill side,” as they said. “Quantrill Side” shows this, and another vocal piece, “The Nature of the Guerrilla,” adds to the romance surrounding the bushwhacker. My Jesse James review likewise included a quotation from this piece. The song, interestingly enough, is found in Kansas folksong collections but not in any from Missouri, and its rousing tune and lyrics are definitely pro-Quantrill as it whoops up the joy of burning down Lawrence, Kansas.

A different take on Quantrill is “Kate’s Song,” composed and sang by Cathy, offering a woman’s view both of this enigmatic leader and her choice to join him:

His blue eyes made you think if ice and a chilling winter’s day;

My papa told me eyes were like a window to the soul;

But not so with this handsome man who kept the shutters closed.

As a guerilla’s wife, Kate is described as being on the run but happy, like the heroine in the folk song “Gypsen Davey,” who is also happy with life on the road, on horseback, sharing danger:

Sometimes we’d race till all I knew were pounding hooves and wind,

And it made him smile to see me ride my horse just like a man.

Another rousing campfire song, “Joe Shelby’s Mule,” is a combination of Joseph Leddy’s 1864 lyrics and a minstrel tune. It was a Missouri hit, even overtaking “Dixie.” From this rollicking piece, the album moves to “The Last Great Rebel Raid,” an original song by Bob Dyer recalling the final, doomed Confederate invasion of 1864. Its melodic, quiet defiance leads into “The Knot of Blue and Gray,” a somber traditional song sung to the tune of “The Wearing of the Green,” recalling the loss of brothers in the war. In Cathy’s strong, plain, and retrospective voice, she laments:

But the same sun shines on both their graves,

O’er valley and o’er hill,

And in the darkest of the hours

My brothers they lie still

As the singer wears a broad band of blue and gray.

The song fades into an instrumental rendition of “Hard Times Come Again No More,” the Stephen Collins Foster song that, like so many of his, recalls the loss of the plantation life he seemed to prophesize in his sentimental ballads.

The comingling of suffering and respect on both sides was the traditional way of viewing the Civil War, and is the one I was brought up with. It was recognized that there were bloody differences, but in time both sides reunited and were accepted as one nation again. As a radio piece that was broadcast in my youth put it, there was no more animosity: “Shake hands, Reb. Put ‘er there, Yank.”

This is no longer the case, as the antebellum South and its cause is treated as something demonic, and all the Southern history, statues, and viewpoints are being expunged by . . . the North. Perhaps, as some say, it was a new and blind ideology that emerged as a reaction to Trump’s election, but which had already lying dormant, waiting for the spark: the last roar of Northern supremacy.

* * *

Rebel in the Woods adds texture to the collection and, like the best recordings, doesn’t just offer music but also tells a narrative. “The Call of Quantrill” is a campfire song, sung with a kind of homey feel by the trio, a song said to be much beloved by Jesse James and Bloody Bill Anderson as well as many Confederates who fought on the border. A switch comes in “The War in Missouri in ’61,” a Northern song celebrating (again) the rout at Camp Jackson, sung a cappella as a sturdy, camp-meeting hymn. This underscores the religious overtones that Northerners brought to their cause. The bushwhackers sing of freedom; for a guerrilla, it is wistful, temporal, and may be gone with the next Yankee attack, but it’s there.

“Missouri, Bright Land of the West” is the most ambitious song, recalling a period feel. Sung by a trio accompanied by piano, guitar, and mandolin, it has a real parlor feel to it:

Missouri! Missouri! Oh, where thy proud fame!

Free land of the west, thy once cherished name,

Now trod in the dust by a despot’s command . . .

It restates how the Southerners saw themselves as the ones who had been attacked, while the Northerners believed they were bringing a new world of freedom. The music delineates the camps as those wishing to be left alone and those who want a brave new world . . . of union. The song was composed by Harry MacCarthy, who also composed “The Bonnie Blue Flag,” which was second only to “Dixie” as the Confederacy’s theme song. This song never hit those heights, but nevertheless expresses a genuine desire to preserve a way of life that was imperiled by the needs of a new America.

Immigrants were generally expected to side with the Union, as the Germans did wholeheartedly, but in “Kelly’s Irish Brigade,” set to the tune of “Columbia, the Gem of the Ocean,” we hear of the Irish who joined the loyal Missourians.

“Rebel in the Woods” is a song that evokes the beauty of the land and pleasures of the vernal season:

The winter is gone and the spring has come once more,

The rebels rejoice that the winter is no more,

For now it is spring and the leaves are growing green,

And the rebels rejoice that they cannot be seen.

The bushwhackers are pleased that nature is finally offering cover so that they can raid, ambush, maneuver . . . springtime’s emergent beauty also sums up the natural symbiosis of the people defending their land that will also shield them. And the hope of victory?

And when we are joined in wedlock’s happy band,

Then we never more will take the parting hand.

And at home, soon home, home we will be.

This was a “pome” published in 1863, then put to the tune an old folksong taken from traditional sources.

Songs about various rebel leaders on this album are jaunty and not too far removed from the good old C&W style with popular tunes usually grafted on, but “Daniel Martin” is the opposite: an earthy, a cappella song about a Union soldier recalling his enlistment and then whipping Sterling Price’s forces. It is a compilation of three traditional tunes associated with this determined Arkansan who is ready to whack the “Secesh,” sung in sharp-note style and reinforcing the choral, semi-religious tone the Union songs often have, recalling hymns sung by Puritan soldiers in the English Civil War — of which the American Civil War was often a rehash.

The album’s final four selections are a final coda to the war itself.

“Anderson’s Warning” is an original song composed and performed by Cathy about Bloody Bill Anderson, probably the most notorious bushwhacker, who has been judged by history to have been a ruthless killer. A woman’s voice thus depicts a poignant menace from the past:

I can’t save you traitors from a terrible end,

Like wolves we will hunt you down both me and my men.

Fools that you are, you can’t run and hide;

My eyes will be on you; watch how you decide.

Cathy’s tone is colder than any man’s. A ruthless killer who scalped his enemies? Certainly. Furious at the Union because his sister had died in their forces’ custody, and thus seeking eternal vengeance? Most certainly. Her ballad paints textures of understanding, if not sympathy, for Anderson’s words warn from history, matching his young, cold face staring back in his photograph:

My name’s Captain Anderson; I hunt and kill.

I am a guerrilla. I’m a Devil from Hell.

This leads into “Wakefield,” a rousing fiddle tune celebrating the place where Quantrill was hiding before he was discovered and killed by a Captain Terrell. Terrell had switched sides and had become a ruthless and cruel officer. He died a year after Quantrill, and a Louisville paper noted that “no man ever more richly deserved a torturous death.”

[6]

[6]You can buy Tito Perdue’s Love Song of the Australopiths here [7].

“Wakefield” is fast and furious, set to a frantic rhythm recalling a chase, or a hunt, as the rebels are worn down. It recalls the contra dances I went to, Wakefield begging for caller and dancers to go do-si-do! Circle right! Swing your partner! Interestingly enough, Cathy went to Wakefield to research the tune and discovered that she was a descendant of Terrell. It’s a pulsing tune that leads into “Jesse James,” where Bob sings the original ballad, then Jim Dyer offers his own rendition, and like many songs in this collection it is a blending of old and new, in effect revitalizing history. Dave sings the traditional ballad while Bob’s version offers a deeper commentary on this dark hero of the period.

The collection concludes in an offbeat, thoughtful way with “Gone to Kansas,” a song whose origins lay in one of the usual minstrel numbers about the darkie’s gay life on the plantation. But this setting, in an Irish-like sadness, brings to life the actual situation at the end of the war for the freed slaves who, while now free, drifted aimlessly, many not knowing what their place in the new Yankee world was going to be.

Many black songs of the Civil War were hopeful and jubilant. Henry Clay Work (1832-1884), who wrote “Marching Through Georgia,” also did a tune about an Uncle Joe happily singing “Hail Columby” in celebration of his freedom, and “Kingdom Coming” was another darkie song where Work praises former slaves who watch as their masters flee the Yankees. They sing “De massa run, ha-ha! / De darkie stay ho-ho!,” and help themselves to the booze and ham, toss the overseer in the well, and load up on the food, since it will all be “Cornfiscated when de Linkum soldiers come” — which was basically the truth. It almost sounds — minus the minstrel dialogue — like the slogans of a BLM rally.

It is also interesting to note that while Work always took pride in “Marching Through Georgia,” but whenever William Tecumseh Sherman heard the song, he immediately left the room.

In “Gone to Kansas,” the mood is one of solitary loss and abandonment:

Can’t you hear the owls a-hooting in the darkness of the night?

It brings a drop of sweat on my brow.

Oh, I feel so awful lonesome, I fear I’ll die from fright,

Since the cabins are all empty now.

There were blacks who went to Kansas to try to begin a new life, but many others stayed and began a dislocation that has morphed into the welfare state. As one man I knew put it, “We never had problems with the colored. Everybody got along, but the colored always expected the white folks to take care of them.”

Thus it is the blacks, who were the ostensible reason for the Civil War being fought, who end this collection — not in triumph, but in uncertainty and mordant solitude.

I am impressed with the talent on this album. Dave, Cathy, and Jim have beautiful and natural voices for recalling Missouri’s great war. It is an aural equivalent to Edgar Lee Master’s Spoon River Anthology, where a cemetery brings forth an outpouring of emotion and loss. The Missouri accents can twang and drone, but also be clear and hard when needed. I feel a special link to these people because I knew them, and this is my state’s music. I wish folk music could be better appreciated and utilized by people who want to reassert pride and strength in average people. Folk music is white music, but it can also be a genuine mingling of and borrowing from other cultures and races. Instead, folk has been taken over by the Left. The Right, in many cases, has simply abandoned the traditional arts.

In the sixties, folk was always aimed at the Left. I think of Judy Collin’s “Hey, Nelly Nelly,” singing of the 1850s in a paen to Lincoln:

And says them black folk should all be free

And walk around the same as you and me . . . and it’s 1858.

Well, Lincoln never quite said that at the time. But we move on to 1861 to go fight; then, in 1865, Lincoln is dead and:

I see white folks and colored walkin’ side by side

They’re walkin’ in a column that’s a century wide

It’s still a long and a hard and a bloody ride

In 1963.

Folk therefore has its propaganda value, and it certainly did in the sixties, before it was swallowed by rock.

Too many people have succumbed to rock, pop, and rap, allowing manufactured, corporate music define their taste.

I’ve always felt that rock is defined by the beat, and folk music by the drone. The drone is like a bagpipe, recalling the time when we were tied to the soil and all the pain that entails — a lament, but also lullaby. Rock’s beat is more sexual, pulsing, and sensual, offering youthful freedom and liberty — an internationalized and manufactured format refined and packaged by corporate interests.

Thus I’m very thankful for Johnny Whistletrigger and its music rooted in Missouri, and in the ghosts of the war my ancestors fought in (on both sides). It is the perfect coda to Stiles’ book — a Thomas Hart Benton mural of sound where the past is not forgotten, but a shadow walking alongside you.

* * *

Like all journals of dissident ideas, Counter-Currents depends on the support of readers like you. Help us compete with the censors of the Left and the violent accelerationists of the Right with a donation today. (The easiest way to help is with an e-check donation. All you need is your checkbook.)

For other ways to donate, click here [8].