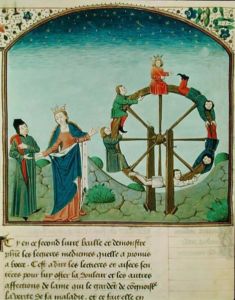

Boethius’ Wheel:

On The Consolation of Philosophy

Posted By

Mark Gullick

On

In

North American New Right

| Comments Disabled

This is my art. This is the game I never cease to play. I turn the wheel that spins. — Boethius, The Consolation of Philosophy

The wheel also appears in alchemical texts as a symbol of spiritual ascent and descent. — Richard Cavendish, The Tarot

When it is suggested that someone who has suffered a wrong or misfortune “be philosophical” about the unwelcome turn in their affairs, we understand it to mean “stoical” or perhaps “thoughtfully accepting.” In the history of Western philosophy, although there have been many reversals of fortune, it is not easy to think of fate executing as great a volte face as she did to Ancius Manlius Severinus Boethius in the first quarter of the sixth century.

Known to posterity simply as Boethius, here was a man who, as is often said of modern crime victims, was in the wrong place at the wrong time. Born into Roman wealth in 480, Boethius entered politics, not only becoming Consul himself but siring two sons who also held the consulship.

Politics and philosophy were linked far more in the Classical world than they would be after the Dark Ages, despite Plato’s prescription for rulers to be philosophers and vice versa. Plato himself was a member of the Athenian Council, and Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius, Senator Seneca, and Consul Cicero all left important works for posterity. In the case of Boethius, his most famous work, one of the most influential in philosophy’s history, was inspired by a singular occurrence: He went to jail.

In 489, the Balkan Ostrogoths (not an eastern European metal band, but rather a violent and tribal people originally from what is now Ukraine) invaded Italy and installed Theodoric as King. This duplicitous and treacherous thug would become increasingly paranoid and begin jailing his enemies, real or perceived. Boethius was deemed to be one, and was imprisoned and executed within a year in 523. Already an established philosopher, Boethius was primarily responsible for the transmission of Greek philosophy to the Middle Ages, having translated Aristotle’s works into Latin. But it was incarceration that would bring him the strange visitation that led to one of the most important and famous of philosophical texts, The Consolation of Philosophy.

There have been many great works of literature written in prison. Books written at least partly while the author was in chokey include Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Mort d’Arthur, Jean Genet’s debut Our Lady of Flowers, Ezra Pound’s Pisan Cantos, Cervantes’ Don Quixote, and Sir Walter Raleigh’s History of the World. Antonio Gramsci, Oscar Wilde, and The Marquis de Sade all wrote screeds under lock and key. Gramsci was imprisoned by Mussolini, whereas Pound was held in Pisa by the Americans for broadcasting in favor of il Duce. Wilde was held as a result of a failed libel case after being convicted of gross indecency, and Sade, much as I admire his work, because he was as mad as a wet hen. Boethius’ incarceration really belongs in the Gramsci category, as it was purely political. Just think: If Mussolini had gone for cashless bail, Gramsci might never have written The Prison Notebooks, there might have been no long march through the institutions, and we would all have been saved a lot of trouble.

The text of the Consolation begins with Boethius’ lamentations, first in verse and then in prose. This alternate structure continues throughout and gives a Greek dramatic feel to the whole, with strophe and antistrophe. If you already know Boethius (or even if you don’t,) this is a wonderful short film [2] about two scholars from Cambridge reconstructing the songs from the Consolation. But a song is not effective without an audience, and Boethius is soon paid a visit by one of the most memorable characters in the limited dramatics Western philosophy offers: philosophy herself.

While the jailed Consul is bemoaning his fate, there appears in his lonely cell “a woman of exceedingly venerable countenance” with “eyes as bright as fire.” Boethius’ description of her size is hallucinogenic:

Her stature was difficult to judge. At one moment it exceeded not the common height, at another her forehead seemed to strike the sky.

Her garments, which she had woven herself, were striking and yet a little shabby, bearing the Greek letters Π (pi) and θ (theta). These represent the two facets of philosophy, the practical and the theoretical, and there is a staircase connecting the two. The lady’s robe has also suffered damage, and “had been torn by the hands of violent persons, who had each snatched away what he could clutch.”

The lady is Philosophy, also later referred to by Boethius as “Lady Fortuna” for reasons vital to Consolation’s central message. Her first action in Boethius’ cell is an angry Platonic one. She banishes poetry:

And when she saw the Muses of Poesie standing by my bedside, dictating the words of my lamentations, she was moved to wrath. “Who,” said she, “has allowed you play-acting wantons to approach this sick man?”

Just as Plato cast out the poets from the res publica, so too Philosophy cleans house. It is clearly the arguments of philosophy Boethius needs, not to wallow in sorrow and poems. “The time calls,” she says, “for healing rather than lamentation.” And this healing comes with acceptance of the way of fortune, the realization that reason can only go so far before the wheel of fortune takes over. Fortune is heartless and blind, as she is often depicted in art. Merit is nothing to her, and only occurs in nature at the dictates of providence. It would have instructed Boethius, she says, to have learned of the fates of Arrius, Seneca, and Soranus, men who “were brought to destruction for no other reason than that, settled as they were in my principles, their lives were a manifest contrast to the ways of the wicked.”

[3]

[3]You can buy Mark Gullick’s Vanikin in the Underworld here. [4]

And so Philosophy begins both her ministration of Boethius and her transformation into Fortuna. Boethius, she says, fails to know his own nature and so mistakes the workings of fortune, which takes the central metaphorical image of the wheel. The wheel is inextricably linked with the notion of fortune both good and bad and has been from Ixion to roulette. It is surely no coincidence that the Tarot card depicting the Wheel of Fortune is placed at the center of the Major Arcana of the traditional pack. Whether the wheel of fortune is part of the grand cosmic design or turning slowly in a casino somewhere, fortune — and fortunes — will be decided on its turn.

Like today’s stock market, the wheel can move up or down, the difference being that companies advertising their shares are obliged to tell you that, whereas life is not. That is where Lady Fortuna comes in. It is not the nature of the universe to be anything other than it is. Mankind is subject to the wiles of Fortune: “Thou deemest Fortune to have changed towards thee; Thou mistakest. Such were ever her ways, ever such her nature.”

And her nature is bound up with movement, movement and rest being still woven together with neo-Platonic views of the universe:

What? Art thou verily striving to stay the swing of the revolving wheel? Oh, stupidest of mortals, if it takes to standing still, it ceases to be the Wheel of Fortune.

Philosophy’s admonition continues. Boethius’ lack of understanding reduces to his lack of self-knowledge. Much of Philosophy’s sage advice revolves around the Delphic injunction of knowing thyself: “If then, thou art master of thyself, thou wilt possess that which thou wilt never be willing to lose, and which Fortune cannot take from thee.”

This is the realization that not only is Fortune blind, and lamentation at her curses unsustainable and self-destructive, but that life cannot be judged good or evil according to the proportion of benevolent providence she has allotted the individual. Ill fortune, says Fortuna herself, is worth more to a man than good fortune because it is more instructive. In line with a tradition that would last at least 1,400 years in the West, it is what happens to the soul — the divine part of Man — that is vital, not the vagaries of bodily existence.

Given that Consolation became such a staple of educated and erudite Europe, its more hidden themes are also worth paying attention to. From at least Plato to the Renaissance, aided and abetted by the Church, there was a radical dualist dichotomy underpinning all permissible belief systems: The soul is superior to the body. This explains the sheer Platonism Philosophy embodies when she says that “[t]hese things seem to give to mortals shadows of the true good, or some kind of imperfect good; but the true and perfect good they cannot bestow.”

This is a familiar anti-somatic Platonism. In the Timaeus, Plato sums up his view of the body as “that shadow which keeps us company.” This anti-body — as it were — stance would, of course, be a central supporting pillar of the Christianity whose metaphysical framework neo-Platonism would eventually fund.

As a sort of cinematic trailer for the philosophical concerns of the next millennium and a half, the Consolation is an essential book for any student of philosophy, particularly at the start of their study. Kant is foreshadowed:

Men think that all knowledge is cognized purely by the nature and efficacy of the thing known. Whereas the case is the very reverse: all that is known is grasped not conformably to its own efficacy, but rather conformably to the faculty of the knower.

Schopenhauer and Nietzsche are both heard in advance of themselves:

Providence has furnished things with this most cogent reason for continuance: they must desire life, so long as it is naturally possible for them to continue living.

There is even a clue that Shakespeare may have enjoyed the Consolation on his days off. And so Lady Philosophy, “[s]o true it is that nothing is wretched, but thinking makes it so,” will be echoed by Prince Hamlet a millennium later: “There is nothing either good or bad but thinking makes it so.”

The Lady Philosophy/Fortuna also foreshadows Descartes’ rather dubious argument for the existence of God from the ontological argument a millennium later, and the central argument of Philosophy concerning providence and the existence of free will remains unresolved — because unresolvable — to this day. The greatest intellectual contest, I think, over the notion of free will is that between Luther and Erasmus in the sixteenth century.

Also, Philosophy’s argument has as its center of gravity the ultimate unknowability of God and his machinations, at the same as possessing, via philosophy, the ability to see his creation as perfectly designed. As Boethius begins one of his lyrics:

Wouldst thou with unclouded mind

View the laws by God designed.

The ultimate law, as Philosophy/Fortuna explains to Boethius during visiting time at the jailhouse, is that although God can see all (existing as he does in an eternal present tense encapsulating all of eternity), then fortune as a direct descendant of providence can send us no evil, despite evidence to the contrary:

Since every fortune, welcome and unwelcome alike, has for its object the reward or trial of the good, and the punishing or amending of the bad, every fortune must be good, since it is either just or useful.

Hopefully this was some consolation to Boethius, as very shortly after he finished Consolation, Theodoric’s men brutally killed the imprisoned ex-Consul. Some say Theodoric dealt the death-blow himself. Theodoric himself would be dead within a few years but, although he and his men killed the author of the Consolation, someone kept the book, which went on to influence Western culture at its core. Perhaps Philosophy herself, the Lady Fortuna, left it lying around in plain sight for the executioners to find. Chaucer translated it into English, and Dante — as well as including Boethius among the sages of the Circle of the Sun in the Paradiso — incorporates many of the ideas of the Consolation.

The Consolation of Philosophy deserves its place in the pantheon of Classical philosophy alongside Plato’s Republic, Aristotle’s Metaphysics, Lucretius’ On the Nature of Things, and others which have enriched the succeeding traditions and providing Western philosophy with its competing narratives and core ideas. As for Philosophy herself, in a Western world increasingly feeling like a prison, we are fortunate to have such a cellmate.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “Paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

- Third, Paywall members have the ability to edit their comments.

- Fourth, Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected] [5]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

- Fifth, Paywall members will have access to the Counter-Currents Telegram group.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[6]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[6]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.