The American Colonization Society

Posted By Morris van de Camp On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledEric Burin

Slavery & the Peculiar Solution: A History of the American Colonization Society

Gainesville, Fla.: University of Florida Press, 2005

See also Herman Husband [2] & Hinton Rowan Helper [3]

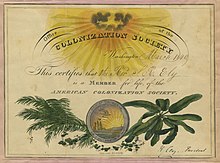

The American Colonization Society is an organization whose mission, had it been successful, would have turned America into a white ethnostate and nipped a great many troubles in the bud. Unfortunately, while the American Colonization Society did successfully create a functioning society of ex-slaves in Africa and repatriate formerly enslaved sub-Saharans to their native lands, the numbers of repatriated didn’t make enough of a difference.

The story of colonization is here told by historian Eric Burin [4] of the University of North Dakota. The idea first appeared less than a century after the disaster of the sub-Saharan’s first arrivals in Jamestown [5] in 1619, in 1714. A resident of New Jersey proposed that slaves be set free and sent back to Africa. It was the first call in America for a white ethnostate. One can only imagine the benefits had a repatriation policy been seriously carried out in 1714.

From 1714 until independence, slavery existed across all of the original 13 colonies, although not to the same degree:

Two-thirds of the mainland colonies’ 469,000 bondpersons dwelled in the Chesapeake region. Another 20 percent resided in Georgia and South Carolina. Approximately 10 percent toiled in the Mid-Atlantic and New England colonies. All totaled, one in five Americans was enslaved at the time of the Revolution. (p. 6)

In South Carolina in particular, the ration of slaves to masters was pretty high. That colony was founded by West Indian planters who envisioned a slave-intensive plantation economy from the get-go.

Although the American War for Independence was a revolt by whites against what they believed was foreign rule, the conflict’s ideology had within it universalist aims of freedom for all. After independence, anti-slavery activists therefore started to eliminate the practice. This was easiest to do in New England, where there were the fewest slaves. The territory of Vermont [6] ended slavery in 1777. The rest of New England ended slavery through a series of judicial and legal processes over the next few decades. The Mid-Atlantic states began to abolish slavery between 1780 and 1804, but the emancipation was designed to be gradualist, with sub-Saharans remaining in bondage until they were 28.

It was in the North at this time that pro-slavery ideas took shape. These ideas wouldn’t make it to the South for several decades. A similar process took place in relation to segregation: It originated in the North and was adopted in the South a decade or more after Reconstruction ended.

Founding the American Colonization Society

The founding of a society with the specific aim of repatriating all sub-Saharans to their native lands started with a drinking party. Charles Fenton Mercer [7] was putting them away with Dabney Minor [8] and Philip Doddridge [9]. All of the drinkers were politicians. Doddridge, a Federalist from what is now West Virginia, suddenly exclaimed that Thomas Jefferson was a hypocrite. When Mercer demanded proof of this charge, Doddridge explained that Jefferson had advocated for sub-Saharan repatriation in his Notes on the State of Virginia. When the Virginia’s state legislature passed an act to do just that, Jefferson evaded the matter as President. Intrigued, Mercer began to draw up what would become the American Colonization Society.

Mercer’s motivations for repatriation amount to race realism. He believed that Divine Providence has made the races antagonistic. Furthermore, he reasoned that sub-Saharans would never ascend in society. As this fact became increasingly obvious, free blacks would fall into subversion and crime. Mercer felt that colonizing them would bring sub-Saharan Africa a population that was Christian, knowledgeable in more advanced forms of civilization, and that could establish commercial relations with a slave-free South, thus improving themselves and Africa.

The project gained a great many high-profile supporters, including Francis Scott Key, who wrote what would become the United States’ national anthem, and Bushrod Washington, the nephew of the first President. Incidentally, had George Washington become a king, there is a considerable case to be made that his nephew Bushrod would have inherited the position. As it was, Bushrod was a Supreme Court Justice. Support for sub-Saharan repatriation was therefore high, indeed.

The rank-and-file of the American Colonization Society was an ideological and regional mix of “proslavery planters, Piedmont vacillators, Southern modernizers, and Northern evangelicals . . .” (p. 14). The first order of business was to sidestep the slavery issue entirely. The reason for this dodge was that many of the slave owners who supported repatriation were touchy about the subject. Their motivations boiled down to the idea that sending free sub-Saharans to Africa would undercut slavery, to explain it simply.

The Quakers [2] were especially prominent in supporting repatriation:

For decades, Friends in the Tar Heel State had expressed their distaste for slaveholding, but the group had failed to act boldly on the issue, an indecisiveness born of their decentralized, consensus-oriented system of governance and North Carolina’s prescriptive manumission laws. Many of the state’s Quakers simply gave their bondpersons to the sect itself. By the 1820s, the Society of Friends in North Carolina owned hundreds of slaves. The body attempted to settle some bondpersons in Haiti, but after one disastrous expedition to the Caribbean nation, the group turned its attention to Liberia. Between 1825 and 1830, 398 North Carolina blacks emigrated to Liberia, the majority of whom were sent by Friends. (p. 36)

If this seems contradictory, it’s because it is. Slavery was an institution filled with contradictions. Many slave owners liked their slaves. They also beat slaves who were troublemakers. Often, anti-slavery activists were motivated by a visceral dislike of sub-Saharans. The same contradictions pertaining to racial matters today animated the nineteenth century’s social reformers as well. Nonetheless, all of those in the American Colonization Society wished to see the project succeed, and potential emigrants were educated to be productive citizens in Liberia.

[10]

[10]You can buy Greg Johnson’s It’s Okay to Be White here. [11]

The American Colonization Society gained support from the Federal Government in the form of funding. Additionally, the United States moved to colonize what is now Liberia. The capital city, Monrovia, was named for President Monroe and founded in 1822.

There was also the Pennsylvania Colonization Society. It raised enormous sums to remove sub-Saharans from Pennsylvania, but in the end it only removed 300 from a population that eventually numbered 57,000. Most of their money was spent on freeing slaves in the South. They also paid to defray the costs of sending transport ships to Liberia. The Pennsylvania Colonization Society eventually abandoned its project as the problems leading to the Civil War became too huge to avoid any longer.

Despite the obvious benefits of avoiding political polarization over slavery – namely, making America into a white ethnostate while improving Africa — many top American politicians were not entirely happy with the idea of colonization. Bean-counters complained about the costs, while radical abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison disliked the anti-sub-Saharan attitudes implied in the proposal and felt that repatriation propped up slavery by removing troublesome slaves. For their part, pro-slavery politicians felt that repatriation schemes chipped away at slavery. President Andrew Jackson and South Carolina Senator John C. Calhoun were cold toward the project, mostly due to concerns over slowing slavery’s growth.

Free sub-Saharans were divided over the matter. Most deplored the idea. They harassed Society agents and disrupted emigrant expeditions. Others saw the obvious benefits and took the leap to colonize their homeland. The first colonists and their descendants would go on to dominate Liberian society and culture for decades thereafter.

Manumission & Emigration

The Jackson administration turned out to be highly critical of repatriation. By 1830, pro-slavery activists felt that the American Colonization Society was a threat to their status and that they were able to influence Andrew Jackson’s priorities. As a result, the Jackson administration began a politically-motivated investigation into the society. This investigation was not entirely unwarranted. The Federal Government had spent a great deal of money on the American Colonization Society, yet few sub-Saharans had been repatriated. Additionally, one of the Society’s aims was to repatriate illegally imported sub-Saharans, and few of them were being repatriated. The main problem boiled down to economics.

Slavery was profitable, and slave owners were the critical piece of the entire affair. Those who wished to manumit their bondsmen paid an economic price for every slave freed. Manumission, or release from slavery, usually only occurred when the slave owner was old or dead, and only if that slave owner’s children were set up with a considerable inheritance of their own. Other freed bondspersons were against going because of various social connections. Additionally, ex-slaves had ample opportunities to find jobs in the expanding cities, especially places like Baltimore. In the early nineteenth century, Baltimore was the most economically and culturally viable city in the United States, much like Houston in the 1970s or Seattle in the 1990s.

As a result, manumission and repatriation became the project of a narrowing circle of slave owners in a small part of the United States, specifically western Virginia and western Maryland. Indeed, repatriated sub-Saharans in Liberia duplicated the society of the western fringe of the Tidewater. Liberian culture was one of Masonic lodges and low-church Protestants, and its politics was dominated by the Liberian Whig Party [12] until the 1980s.

As the controversy over slavery increased in the 1850s, influential men in Washington continued to support the endeavor. These included Daniel Webster, Edward Everett [13], Henry Clay, Stephen Douglas, and Millard Fillmore. They all called for repatriation, but the actual policy was clipped. Proposals for a federally-subsidized mail route to Liberia were dropped in committee, despite the fact that such a route would have made repatriation easier.

Nonetheless, this decade was when the highest numbers of freed sub-Saharans were repatriated. The sheer number of these newcomers also disrupted the colony. The best jobs in Liberia were being held by the original settlers of the 1820s and their descendants. The new emigrants were unable to find jobs, and there wasn’t an expansion of freed slaves into the hinterlands as there was of white emigrants into America’s frontier. On top of all this, Liberia nearly suffered a civil war.

In the United States, the political scene was likewise deteriorating. The compromises over slavery’s expansion were failing to solve any of the problems. Additionally, longstanding differences between the various regions were exploding. The Kansas Territory descended into violence. Alarmed pro-slavery politicians circled the wagons.

In 1857 Hinton Rowan Helper [3] wrote The Impending Crisis, which heavily criticized slavery and called for the repatriation of sub-Saharans. The Republican Party had also been formed, and many of its early members were in favor of repatriation, including Abraham Lincoln [14].

Abraham Lincoln & Colonization

Abraham Lincoln was the first American President who genuinely wished to carry out repatriation. Indeed, it was part of his war strategy. To keep the Border States within the Union, he put men from those states on the repatriation committees. He also proposed and won legislation in Congress to set aside federal funds for repatriation. His main two destinations for colonization were Haiti and Liberia.

All the emancipation measures adopted by the Lincoln Administration in 1862, the time of the Battle of Antietam and the Emancipation Proclamation, came along with endorsements and proposals for repatriation. Even those sub-Saharans who had been cold to the measures earlier, such as Frederick Douglass, lessened their resistance to it at this time. On August 14, 1862 Lincoln met with a delegation of sub-Saharans and encouraged them to emigrate. One colonization scheme was in the Chiriqui region of New Granada, in what is today Panama and Colombia. It failed. In the end, Lincoln was an aggressive abolitionist mainly because he was an aggressive colonizer.

By 1863, repeated failures dampened enthusiasm for repatriation. Congress, then controlled by the Unionist Democrats, froze the funding for colonization. The American Colonization Society remained viable during this time, and even after the Civil War, however — 2,000 sub-Saharans migrated to Liberia between 1866 and 1871. Interest peaked again after Reconstruction ended. Yet, by 1904 the Society stated that “it is now regarded as chimerical to attempt to send the entire mass of Negroes back to their native land.” (p. 166) The Society shifted to supporting Liberia through aid after this. In 1913, it donated its papers to the Library of Congress. The final donation of papers took place in 1960.

Reasons for Failure

There are many reasons for colonization’s failure. The first is that America’s pro-slavery wing resisted the project to the last possible moment. Another was the staggering costs that had to be paid to send even a single person to Liberia, and these costs were usually covered by a slaveholder who had moral qualms about slavery. Those willing to support repatriating their slaves tended to be wealthy Virginians or Marylanders, as they had to hedge the costs of emigration against their ability to remain solvent and still offer some inheritance to their children. The Civil War got in the way, also. Besides all of this, the colonies themselves failed to prosper. Liberia never became an economic powerhouse. Its income was mainly derived from registration of shipping, a niche in which it eventually lost much market share to Panama. Lastly, sub-Saharans themselves were cold to the idea.

All is not lost. Many of the most aggressive integrators of the 1960s relocated to Africa. W. E. B. Du Bois left America for Ghana in 1960 and died there at the age of 95. David Robinson, the son of the baseball desegregationist Jackie Robinson, moved to Tanzania and became a successful coffee farmer.

Decolonized Africa has failed to prosper. An idea fielded by colonial supporter Bruce Gilley has been to set up colonies on islands just off the African mainland. On them could be set up systems similar to that of Hong Kong, centered on banking, transportation, manufacturing, and so on and operated under American or European laws and governance. Should that occur, there is a skilled African diaspora that could make a go of it by relocating there.

During the nineteenth century, Liberia was an underfunded project which dumped a small population into a wilderness. Should “hong kongs” be set up, it might be possible to quickly build up an area and make it prosperous. One can hope.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “Paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

- Third, Paywall members have the ability to edit their comments.

- Fourth, Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected] [15]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

- Fifth, Paywall members will have access to the Counter-Currents Telegram group.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[16]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[16]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.