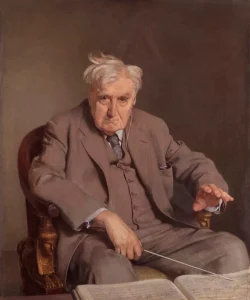

Remembering Ralph Vaughan Williams (October 12, 1872–August 26, 1958)

Posted By Alex Graham On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled2,806 words

Today is the 150th anniversary of the birth of Ralph Vaughan Williams, one of England’s greatest composers. Breaking with the German tradition, which nineteenth-century English composers sought to emulate, Vaughan Williams forged a distinctly English style that drew upon England’s musical heritage. He is also remembered as one of the twentieth century’s great symphonists.

Vaughan Williams was born in 1872 in Down Ampney, a village in Gloucestershire, and grew up in Wotton, Surrey following his father’s death in 1875. Through his mother, he was a member of the distinguished Darwin-Wedgwood family. He was a precocious child and wrote his first composition at the age of six. In his youth, he studied the piano, violin, viola, and organ.

In 1890, Vaughan Williams entered the Royal College of Music, where he studied composition with Hubert Parry (best known as the composer of “Jerusalem”). After spending three years studying music and history at Trinity College, Cambridge, he returned to the RCM in 1895 to study composition under Charles Villiers Stanford. While at the RCM, Vaughan Williams formed a lifelong friendship with Gustav Holst, who was also a student there at the time.

Vaughan Williams’s interest in authentically English music, particularly English folk song and Tudor music, was present early in his career. In 1903, he began collecting folk songs from the English countryside. Over the course of the following decade, he collected a substantial body of folk songs, several of which found their way into his compositions. Vaughan Williams admired folk music for its “sincerity, depth of emotion, simplicity of expression, and, above all, beautiful melody.”[1] He was particularly fascinated by the use of modes in folk music (not all folk tunes are modal, but the use of modes is quite common). In a lecture on English folk music, he contrasts two versions of the “The Miller of the Dee”: one that appears in an eighteenth-century comic opera and one that was sung by a singer in Sussex. The former version was altered in accordance with the conventions of classical harmony: the seventh scale degree is raised and the middle section ends on the second scale degree, clearly to fit the expected V-i cadence, while the latter is in the Aeolian mode and even “cadences” on the flat seventh.[2] Vaughan Williams’s modal language and emphasis on melody are an homage to folk songs and the singers who sang them.

The impact of Vaughan Williams’s encounters with English folk music on his own compositions was swift: in 1904, he wrote In the Fen Country [2], a tone poem meant to evoke the fens of East Anglia, and in 1905-1906, he wrote his two Norfolk Rhapsodies [3], based on tunes he collected in Norfolk.

From 1904 to 1906, Vaughan Williams edited The English Hymnal, arguably the finest collection of hymns in the English language. Though himself an agnostic, he valued the Anglican Church and its place in English history and culture. He searched widely for appropriate tunes for the hymnal, an endeavor which he later described as “a better musical education than any amount of sonatas and fugues.”[3] The final product included a wide range of tunes spanning several centuries and countries, including 31 English folk tunes (including “Kingsfold,” which later became the basis for Five Variants of “Dives and Lazarus” [4] [1939]) and many plainsong melodies. It also included some tunes composed by Vaughan Williams himself, including “Down Ampney,” named after his birthplace, which was played at his funeral [5] at Westminster Abbey.

One of the tunes Vaughan Williams selected for The English Hymnal—sixteenth-century English composer Thomas Tallis’s “Why fum’th in sight”—provided the inspiration for his breakthrough work and arguably his greatest masterpiece, Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis [6]. It premiered in 1910 at Gloucester Cathedral, a location befitting the nobility and spacious architecture of the piece.

Vaughan Williams was very interested in music of the Tudor period. In preparing The English Hymnal, he pored over the ten-volume collection of Tudor church music edited by Edmund Fellowes (whose efforts to revive Tudor music Vaughan Williams greatly admired). He pointed to the Tudor period as a time when musical innovation in England flourished and musicians cultivated a national style instead of mimicking European musical trends. He also noted that the popularity of small-scale forms like the madrigal, the anthem, compositions for the lute, etc. demonstrated that music then was not solely the product of elite patronage, but part of everyday life and the national culture—which puts to rest the notion that the English people are “unmusical.”[4] The influence of sixteenth-century English music on Vaughan Williams is most evident in his sublime Mass in G minor [7] (1921), which blends the polyphonic writing of the period with his own harmonic inventiveness.

English literature was another powerful influence on Vaughan Williams. According to his wife, his favorite authors and poets ranged “from Skelton and Chaucer, Sidney, Spenser, the Authorised Version of the Bible, the madrigal poets, the anonymous poets, to Shakespeare—inevitably and devotedly—on to Herbert and his contemporaries: Milton, Bunyan, and Shelley, Tennyson, Swinburne, both Rossettis, Whitman, Barnes, Hardy and Housman.”[5] Most of the more than 80 songs he wrote are settings of English poems. He was particularly fond of Shakespeare, who features in three of his songs and a few other works: Serenade to Music [8] (1938), which quotes a passage about music from The Merchant of Venice; Three Shakespeare Songs [9] (1951), for unaccompanied SATB choir; and Sir John in Love [10] (1924-28), whose libretto was compiled by Vaughan Williams himself and is comprised of extracts from The Merry Wives of Windsor and a selection of Elizabethan poems.

The premiere of Vaughan Williams’s first symphony, A Sea Symphony [11] (1903-1909), occurred shortly after the premiere of Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis and contributed to his rising fame. Scored for soprano, baritone, chorus, and large orchestra, the symphony sets excerpts from Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. Many composers have written settings of Whitman’s poems, but Vaughan Williams best captures the masculine vitality and expansiveness of Whitman’s verse. Musically, the influence of Ravel, with whom Vaughan Williams studied for three months during the winter of 1907-1908, and French music more generally is apparent in this symphony’s harmonic freedom and use of pentatonic and whole-tone scales. Traces of Ravel can also be heard in On Wenlock Edge [11] (1909), a song cycle for tenor, piano, and string quartet that sets poems from A. E. Housman’s A Shropshire Lad.

A London Symphony [11] (1911-13) was Vaughan Williams’s first purely orchestral symphony and his favorite of the nine he eventually composed. The symphony evokes the many moods of London, where Vaughan Williams spent most of his life, and contains allusions to the city’s soundscape (street songs, the Westminster chimes). The bleak epilogue was inspired by the ending of H. G. Wells’s Tono-Bungay and feels prescient in hindsight: “Light after light goes down. England and the Kingdom, Britain and the Empire, the old prides and the old devotions, glide abeam, astern, sink down upon the horizon, pass – pass.” One senses a similar sentiment to some degree in the The Lark Ascending [12] (1914); written at the close of the Edwardian era, there is a hint of melancholy beneath its tranquility.

When the war began, Vaughan Williams joined the Royal Army Medical Corps, serving as an ambulance driver. He lost many comrades and friends, including the composer George Butterworth. After the war, he wrote A Pastoral Symphony [13] (1921), a moving elegy for the men who died (the title alludes to the fields of France where he served).

The interwar period was productive for Vaughan Williams. The 1920s brought forth the Mass in G minor; the English Folk Song Suite [14] (1923), a cornerstone of the concert band repertoire and one of his most celebrated works; the idiosyncratic Flos Campi [15] (1925), arguably his most pagan work; the oratorio Sancta Civitas [16] (1923-25); his percussive Piano Concerto [17] (1926-31); and Sir John in Love. Vaughan Williams also edited Songs of Praise and the Oxford Book of Carols during this period.

1931 saw the premiere of Job: A Masque for Dancing [18], a one-act ballet inspired by William Blake’s illustrations of the Book of Job. Geoffrey Keynes came up with the idea for the ballet upon acquiring a copy of Blake’s illustrations in 1927. As with Walt Whitman, Vaughan Williams was a perfect match for Blake’s artistic imagination. The ballet is one of Vaughan Williams’s most dramatic works. There is an affinity between Job and his Fourth Symphony, which would be written a few years later, particularly its diabolical scherzo.

Vaughan Williams’s tumultuous Fourth Symphony [19] (1931-34) marked a sharp departure from the contemplative mood for which he was known. Its main theme is comprised of minor seconds, the most dissonant interval; this appears throughout the symphony, most memorably in the third movement. The symphony confused critics, who wondered if he would turn his back on his earlier style. But the boldness and fire of the Fourth Symphony and the celestial beauty of Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis are two sides of the same Blakean vision. The final movement includes an unexpected pastoral interlude right before the symphony’s explosive coda, perhaps suggesting this duality.

The following year, Vaughan Williams penned Five Tudor Portraits (1936), which sets poems by Tudor poet and satirist John Skelton. Each movement depicts a different individual: “Elinor Rumming,” an ale-house keeper; “Pretty Bess,” a young woman; “John Jayberd,” a disreputable clergyman (this takes the form of an irreverent anti-eulogy mostly in Dog Latin); “Jane Scroop,” a girl mourning the loss of her pet; and “Jolly Rutterkin,” a goofy outcast. It brims with character and earthy, ribald humor. Vaughan Williams’s portraits are affectionate and very human, especially Jane Scroop’s lament. I submit Five Tudor Portraits as his most underrated work.

[20]

[20]You can buy Collin Cleary’s Wagner’s Ring & the Germanic Tradition here. [21]

Vaughan Williams returned to a more serene atmosphere in his Fifth Symphony [22] (1938-43), which remains the most beloved of the nine. He dedicated the symphony to Sibelius, who loved it. The third movement is one of the most beautiful pieces of music he ever wrote. Much of the symphony derives from his then-unfinished opera based on John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress, which accounts for its luminous, spiritual aura.

Many assumed that the Fifth Symphony would be Vaughan Williams’s last, as he was then already in his 70s, but he went on to write another, shocking audiences with the menacing, turbulent Sixth Symphony [23] (1944-47). The pianissimo finale and the ominous ostinato in the second movement (calling to mind Holst’s “Mars” from The Planets) make this one of Vaughan Williams’s most unsettling works. He claimed that the inspiration for the symphony was Prospero’s famous speech in Act IV of The Tempest (“We are such stuff as dreams are made on, and our little life is rounded by a sleep”).[6] (He insisted that his Fourth and Sixth symphonies were not composed in response to current events.)

Vaughan Williams’s seventh symphony, Sinfonia Antarctica [24] (1949-52), was born from his work on a score for Scott of the Antarctic, a movie about Robert Falcon Scott’s heroic but ill-fated Antarctic expedition. The score calls for an array of several lesser-used instruments, including a wind machine, glockenspiel, vibraphone, gong, and pipe organ, which create a very atmospheric, cinematic effect, conjuring the image of glistening ice. The success of Scott of the Antarctic was in large part due to Vaughan Williams’s score, which captures the heroism and tragedy of the expedition and the bleakness of the Antarctic landscape. In addition to Scott of the Antarctic, Vaughan Williams composed scores for eleven other films, including the British wartime propaganda film 49th Parallel.

Vaughan Williams demonstrated remarkable stamina and ingenuity in old age. He was 80 upon the completion of Sinfonia Antarctica and went on to write two more symphonies: the lyrical, exuberant Eighth Symphony [25] (1953-55) and the Ninth Symphony [26] (1956-57), whose conception was inspired by Salisbury Plain and Stonehenge and Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles. Other notable works from this period include his Tuba Concerto [27] (1954), the first concerto ever written for the tuba and now part of the instrument’s standard repertoire; A Vision of Aeroplanes [28] (1956), an epic setting of Ezekiel 1 (“I looked, and behold, a whirlwind came out of the North”) for organ and choir notable for its fiery organ solo; and Ten Blake Songs [29] (1957), his last completed composition, which he composed for a documentary about William Blake. At the time of his sudden death at 85, Vaughan Williams was working on a three-act opera about thirteenth-century Scottish poet Thomas the Rhymer.

In addition to his activities as a composer, Vaughan Williams taught at the Royal College of Music, was a visiting lecturer at Bryn Mawr College and Cornell University, wrote articles for musical journals and for the second edition of Grove’s Dictionary of Music and Musicians, served as the president of the English Folk Dance and Song Society for 25 years, and wrote a large quantity of letters (these have been collected into a volume published by Oxford University Press).

Politically, Vaughan Williams was a socialist all his life, but he was no faddish “champagne socialist,” unlike most Leftists of his social class (the Bloomsbury group, for example); he was an authentic populist whose views stemmed from his love for his countrymen and a disdain for snobbery. He believed composers should write for the people and “cultivate a sense of musical citizenship” among them.[7] Never at the expense of quality, however: “The people must not be written down to, they must be written up to.”[8]

Vaughan Williams’s views on nationalism and cosmopolitanism are reminiscent of Herder:

Cosmopolitanism in art means loss of vitality. It is the stream pressing against its narrow banks which will turn the mill wheel. In every nation except ours the power of nationalism in art is recognized. It is this very advocacy of a colourless cosmopolitanism which makes one occasionally despair of England as a musical nation. A few years ago someone invented the very foolish phrase, ‘A good European’. The best European is the most convinced nationalist, not the chauvinist but he who believes that all countries should be different and friendly rather than all alike and at enmity.[9]

Vaughan Williams clarifies that he does not think folk tunes should be shoehorned into a Brahmsian or Wagnerian idiom, or that composers should spend all of their time arranging folk tunes. Instead, composers should seek to capture the spirit of the music of their native soil and use it as a springboard for their own imaginations. Vaughan Williams imbibed the English folk idiom to such an extent that it permeates his music even when he does not quote folk songs at all.

The objections that a composer’s conscious decision to assume a nationalistic orientation is an inauthentic political ploy, or that it restricts one’s creativity and self-expression, are false. On the contrary, in order to find one’s authentic creative voice, one must know oneself, and to know oneself, one must be steeped in one’s heritage. In the words of one of his biographers, Vaughan Williams “discovered a means of self-expression” through his musical nationalism.[10] Vaughan Williams observes that English musicians take to English folk music as one would greet “a well-known but long-forgotten friend.”[11]

Nor does a nationalistic orientation entirely foreclose the possibility of incorporating foreign influences. Purcell, for instance, was influenced by French and Italian music in certain respects. Yet his style was thoroughly English in character.

Vaughan Williams has at times been caricatured as a parochial, backward-looking stick-in-the-mud who wanted to revive an idyllic rural past that “never truly existed” (as they are fond of saying). Apart from the most obvious retort—one need only cite works like the Fourth Symphony, Flos Campi, Job, and the Piano Concerto as counterpoints to his pastoral mood—it is worth stating that even at his most nostalgic, Vaughan Williams was never a slave to the past. He was indifferent to the age of the folk songs he collected and was unbothered by the possibility that a singer he approached might have invented songs on the spot.[12] He sought to evoke not the past, but a timeless, eternal sense of Englishness at once ancient and modern. As he put it in a tribute to Cecil Sharp:

It is not mere accident that the sudden emergence of vital invention among our English composers corresponds in time with this resuscitation of our own national melody. . . . It is not something antique and quaint which Sharp has galvanized into a semblance of life. It is something which has persisted through the centuries, something which still appeals to us here and now and, if we allow it, will continue to develop through all the changes and chances of history.[13]

Notes

- Ralph Vaughan Williams, Vaughan Williams on Music, ed. David Manning (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), p. 29

- , p. 189-90

- Michael Kennedy, The Works of Ralph Vaughan Williams, 2nd ed. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1980), p. 74.

- Vaughan Williams, p. 47.

- Ursula Vaughan Williams, “Ralph Vaughan Williams and His Choice of Words for Music,” (Proceedings of the Royal Musical Association, 1972-1973, Vol. 99), pp. 81-89.

- Kennedy, p. 302.

- Ralph Vaughan Williams, p. 41.

- Kennedy, p. 136.

- Ralph Vaughan Williams, p. 64.

- , p. 46.

- Kennedy, p. 38.

- Ralph Vaughan Williams, p. 195.

- , p. 271.