The Ruin of New Jerusalem

Posted By Morris van de Camp On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledCorrelli Barnett

The Lost Victory: British Dreams, British Realities 1945-1950

Chatham, Kent: McMillan, 1995

I will not cease from mental fight

Nor shall my sword sleep in my hand

Till we have built Jerusalem

In England’s green and pleasant land

— William Blake [2]

We want a society of free men and women — free from poverty, free from fear, able to develop to the full their faculties in cooperation with their fellows, everyone giving and having the opportunity to give service to the community, everyone regarding his own private interest in the light of the interest of others, and of the community; a society bound together by rights and obligations, rights bringing obligations, obligations fulfilled bringing rights; a society free from gross inequalities and yet not regimented nor uniform. — Clement Atlee [3]

. . . [T]he smugness of victory acted on the British like a relaxing drug, ‘Day Zero’ (8 May 1945, when, like a giant machine switched off, Germany lay stopped and silent amid the rubble) inspired the Germans to reach for the shovels and go to work. It makes an apt parable that twelve days after ‘Day Zero’ the first underground train rain again in Berlin, followed two days later by the first bus, while in London no buses were running because the crews were on strike. — The Lost Victory, p. 358

See also: The Collapse of British Power [4] & The Audit of War [5]

At the Yalta Conference in early 1945, where many of the Communist sympathizers on Franklin Roosevelt’s [6] staff were supposedly representing America while actually working behind the scenes to aid the Evil [7] Eurasianist [8] Empire [9], Great Britain was one of the participants. Winston Churchill represented a vast empire at Yalta, and he commanded many squadrons of bombers, fleets of battleships, and large armies of soldiers, and yet his empire was dissolving under his nose.

Today, the collapse of British power during this time seems to be a natural occurrence, like flowers blooming in May. The late historian Correlli Barnett [10] argued, however, that the British Labour Party’s decisions in the aftermath of the Second World War facilitated a massive economic downturn which severely damaged the British economy and further damaged its global position. Specifically, he examined the government of Labour Prime Minister Clement Atlee, who was Prime Minister from 1945 to 1951; its problematic decisions are ruthlessly autopsied.

Post-War

When dawn broke on VE Day in 1945, the British celebrated wildly. They felt that they were great victors. Yet, long-festering problems were about to break out into the open. By the end of the decade, Britain was reliant on American handouts and its economy was in shambles.

The first problem Barnett identifies is basic education. The British upper class received a classical liberal education. They knew everything about the ancient Greeks, and the heady stuff of late Victorian idealism, but nothing about modern industrial techniques

The public schools and the universities of Oxford and Cambridge, with their chapels and their games and their codes of manners, constituted not only brewing vats for this heady stuff but also the jugs by which it was slopped out to successive generations of youth, emasculating the sons of manufacturers and merchants into ‘gentlemen.’ (p. 164)

Meanwhile, those of the British working class were barely educated at all. They usually left school at the age of 14 and went into menial occupations. Even if an ambitious working-class fellow wished to get a vocational education, there were very few technical schools for him to go to.

The British upper class in power was making very poor decisions on the world stage. Barnett focuses on one particular decision: when Britain made a defensive guarantee to Poland in 1939 — which they couldn’t have fulfilled under any circumstances. That guarantee also gave the Poles the ability to drag Britain into a war whether they wanted it or not. When war came, the consequences of the government’s poor decisions n prior decades came to a head, specifically:

- They had allowed treaties with the Japanese to lapse, exposing their Far Eastern imperial possessions to Japanese attack.

- Their enmity with Japan also exposed Australia and New Zealand to mortal danger.

- Most of the British colonies were money-losing propositions. Their populations were mostly low-IQ non-whites who lived under subsistence conditions and had no ability to maintain a civilization on their own.

- The British were forced to defend the massive Indian subcontinent. Not only did they need to use troops to garrison India while England was being threatened by a nearby enemy, they were forced to provide large number of troops for combat operations in the Northwest Frontier and Burma.

- The British alienated Italy to the point that the Mediterranean sea lanes required for passage to India and the Far East were under too great a threat for them to provide any large-scale assistance to their colonies east of the Suez.

- British industry had been gutted by free-trade ideology, so they were utterly reliant upon American support. All high-end machine tools, high-grade steel, and highly technical items were manufactured in the United States.

The British establishment didn’t adjust in a meaningful way to the glaring structural problems that popped up in the aftermath of the war. Prime Minister Atlee recognized that Britain had a problem of strategic overreach, but his staff did not. They remained convinced that Britain should remain a superpower. Thus, when British India gained independence, then becoming several new nations locked in enmity with each other, they could have made a decision to downscale their commitments — but they did not.

The British continued to maintain large troop concentrations in the Middle East, parts of Libya, and Greece, although with the loss of India, Middle Eastern deployments were unnecessary. Additionally, all of these areas were combat hot-spots. In Greece, the British had to support the government against a Communist insurgency. In Libya, there were anti-Semitic pogroms. In Palestine, the British were forced to confront a Zionist terror insurgency which put them up against well-funded and armed ethnonationist Jews backed by the international media.

[11]

[11]British troops conduct a mounted patrol in Palestine. British deployments after the Second World War were expensive and unnecessary.

Barnett served in Palestine at this time. He places this deployment squarely in the pattern of strategic overreach:

In Palestine (ruled by Britain since 1922 under a League mandate) the British government, prodded by the United States, was striving to find some formula for partition that would reconcile the irreconcilable: that is, the claims of Arab and Jew to the same land. In the meantime two British divisions and support troops, some 60,000 soldiers, were stuck in Palestine adding to the balance of payments deficit, carrying out clumsy and ineffective sweeps against the Jewish terrorists who were murdering their comrades, and otherwise doing nothing but guard their own barbed wire. (pp. 60-61)

In 1946 the British took out a massive loan to keep their economy afloat following the end of Lend-Lease aid. This loan was heavily influenced by America First activists, so the American negotiators drove a hard bargain. The key condition was that British money had to be converted into US dollars. This set off a capital flight from the various British possessions in the Sterling Area to the United States.

New Jerusalem

While Britain was still reeling from multiple deployments requiring large amounts of manpower and money, labor woes, an outdated industrial base, and crippling debt, the Labour Party embarked upon a utopian scheme to turn Britain into a New Jerusalem.

[12]

[12]You can buy Georges Sorel’s Reflections on Violence from Imperium Press here. [13]

The New Jerusalem scheme was based on ideas from the late Victorian era: non-conformist Christian teachings alongside socialist ideas supported by the likes of Welsh Protestant miners and social reformers from the industrial cities. It was romantic and unrealistic.

New Jerusalem was not the New Deal. Roosevelt, for all of his faults, was something of a white advocate. He recognized where red lines needed to be drawn, but most importantly his New Deal did not nationalize anything. Under the New Deal, industry was constrained and directed by government, but factory owners were free to do what needed to be done to get production on track. They could issue stock and expand their factories with minimum government involvement. Although unions played a role, New Deal union men ejected Communists and still sought to work hard and make their industries profitable.

Under New Jerusalem, unions were supreme. Communism wasn’t so much an issue as were basic hard work and changing workers to best serve industry. Layoffs and reorganizations were impossible to carry out. Additionally, heavy industries were nationalized. The telephone companies, railways, and coal mines were taken over by the government and managed by officials who had no experience or training in the industry they found themselves in, save one or two of the ministers. Because they were nationalized, the industries couldn’t raise capital by issuing stocks. Instead, they became dependent upon annual outlays from the exchequer. British railroads were unable to expand, and their engines were coal-fired and steam-driven — in a word, obsolete. These steam engines were old and in ill repair, so there were frequent breakdowns, and the trains were often not on time.

To add to the woes, no new roads were built, the telephone exchanges were out-of-date, and businesses couldn’t get new phone lines installed. In the 1940s, if an Englishman needed to make a call, he needed to bring an umbrella, a pocketful of change, and wait in line at the call box.

Energy Policy

Underpinning all of this was an ideologically-driven energy policy. Today, poor energy decisions are made in the name of “climate change” ideology. Britain in the 1940s had New Jerusalem. Coal miners were at the center of this ideology. But the miners themselves had drifted into a culture of strikes and absenteeism. Unprofitable mines couldn’t be closed because the unions did as much as possible to keep them open and the miners working. Even the profitable mines had a difficult time mining enough coal because of labor problems, lack of improved mining techniques, and a dearth of mechanized tools.

Nationalization did nothing to help the mines’ labor problems. Miners went on strike for nearly every reason, including such trivial reasons as someone’s personality clash with the lady who ran the company canteen.

In the winter of 1946/7, New Jerusalem hit its first snag. Europe experienced its coldest winter in decades. The British electrical system failed to keep up, as coal for individual furnaces was scarce due to the antiquated mines that were beset with strikes and lost work hours. The coal that did get mined had to be carried on antiquated rail systems using antiquated steam engines. As a result, there were rolling electrical blackouts – and an unstable power grid meant that industry was yet further slowed.

Squandered Marshall Plan Aid

In 1948, the United States embarked upon a policy of paying European countries to rebuild. This was done out of pure self-interest. Hungry and cold Europeans were thought to be easy marks for conversion to Communism. Britain received more Marshall Plan aid than Germany, but Germany became highly prosperous while the British economy fell behind.

Barnett examined the various nations’ applications for Marshall Plan aid. The German applications focused on using the money to build up their industry. The British applications were rambling documents with little focus.

If a focus could be discerned in what actually transpired, it is clear that construction of housing soaked up resources that should have been invested in modernizing England’s factories. In the late Victorian era, romantic British social reformers saw the slums of the first Industrial Revolution across northern England as shameful. As a result, the children who had grown up in that environment, such as future Prime Minister Clement Atlee and his staff, later worked to remedy the situation.

In doing so, they seemed to have forgotten the Pennsylvania Dutch expression to the effect that while a big barn can lead to a big house, a big house can’t lead to a big barn. Investment which should have gone into electricity, railways, roads, and energy to improve the factories and send workers to government-run vocational schools was rather used to build brutalist concrete apartments such as one sees on the cover of a Led Zeppelin album. Barrett writes:

Such then was the handicap which the British in their social idealism imposed on themselves by their own free choice in the late 1940s, at a time when their military spending in pursuit of the illusion of world power (as against the necessary defense of Western Europe and the United Kingdom) amounted to about 4 percent of GNP. Thus the double pursuit of British dreams and British illusion was costing a total of some 15 percent of GNP. To the massive burden on a war-ruined economy must be added the direct drain on the balance of payments caused by overseas military deployments, as well as the strain imposed by the role of central banker to the Sterling Area. (p. 164)

The Sterling Area consisted of the crumbling empire’s colonies that were increasingly becoming a financial strain and insurgency hotspots.

Poor British Cars Aircraft of the 1940s

The 1940s were a time when there was an incredible demand for products following the austerity of the Great Depression and the war. Had Britain’s industrial capabilities been upgraded in the decades prior and American aid more ably used, England would have remained the workshop of the world. But the Labour government’s focus on prestige products, coupled with years of neglecting technical and vocational training, created an embarrassing series of botched car and aircraft designs.

The British, not unreasonably, had a high opinion of their aircraft industry. Their Hurricane and Spitfire fighters had won the Battle of Britain, and their Lancaster bombers had immolated German cities. Upon closer inspection, however, it is clear that the industry was in trouble as early as 1940.

The British produced several decent military aircraft during the war, such as the Mosquito fighter-bomber, but they were still light years behind the Americans. By 1945, the Americans had a pressurized long-range bombers able to fly at high altitudes: the B-29. By 1946, they had produced the revolutionary B-36 bomber. When propeller-driven military bombers were rendered obsolete by Soviet MIGs in the early 1950s, the Americans developed jet bombers. Additionally, American aircraft companies were producing pressurized and reliable passenger aircraft that were able to make the North Atlantic crossing.

British attempts at capturing this market were a dismal failure. Some of their aircraft, such as the Bristol Brabazon, never even entered service. The Avro York Tudor IV passenger aircraft was also riddled with problems. The Tudor IV successfully entered service in the late 1940s, but then two vanished along with their crews and passengers. The British also developed the de Havilland Comet, which was the first pressurized commercial jet aircraft, but it had problems with metal fatigue. Two broke up in midair. These disasters influenced aviation culture on both sides of the Atlantic. The midair destruction of the Comets clearly influenced the 1951 movie No Highway in the Sky. The story of the vanished Tudor IVs became part of the legend of the Bermuda Triangle.

All was not lost, however. British industry still produced decent fighter aircraft, and the Comet was redesigned and continued to fly for many years afterwards. The Comet, renamed the Nimrod, found excellent use in military applications and was in service until 2011. But the failures in British aviation outweighed the successes.

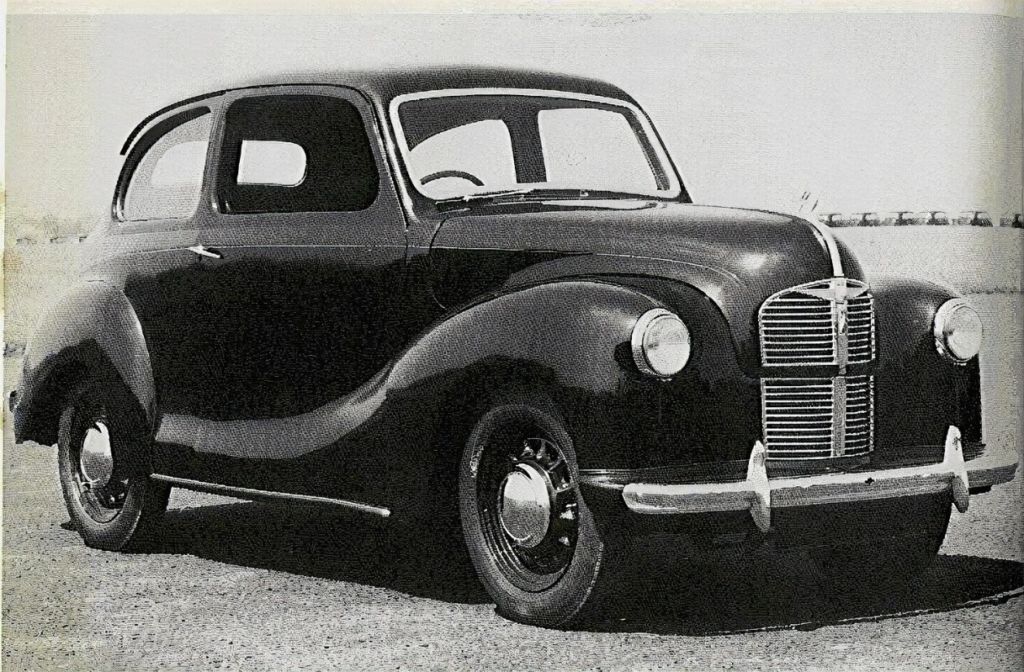

The British automobile industry was even worse. British cars such as the Austin A40 were poorly designed and looked old and stodgy, and there was no service available for them. There was a brief uptick in automobile sales when the pound was devalued in the 1940s, indicating that the British could have taken a good portion of the market, but this uptick failed to be maintained in the face of competition from Ford and General Motors. American cars of the time were state of the art and reliable, and there was a large network of spare parts and services available to drivers.

[15]

[15]The Austin A40 was a sales disaster. Part of the problem with British cars was poor service. The Labour Party’s emphasis on “full employment” kept underemployed workers at full pay where they were not needed. Dockhands could have made more money by fixing British cars, but they didn’t have a chance to do so given that they had few vocational training opportunities.

Reindustrializing the North

Following the end of the war, northern England was every bit as deindustrialized and distressed as the American Midwest following the NAFTA agreement and Chinese “most favored nation” status. This region’s working class was the Labour Party’s base, so they worked very hard to turn the area’s economy around. They relabeled the distressed areas of the north “development areas” and attempted to steer industry that way.

Unfortunately, this failed to work. Labour bureaucrats ended up constraining every industry. For example, the new radio industry was just coming online. Women from northern England sought work making vacuum tubes and other components, but this took manpower away from the textile industry. Making radios was far more profitable and the industry had better work conditions than those who were still weaving cotton on Victorian-era machines, but it was textiles that were given support. Because American aid was directed into housing and foreign military deployments, the textile industry was unable to obtain the resources it needed to adapt, and it was eventually put out of business entirely by more efficient industries elsewhere.

[16]

[16]You can buy Kerry Bolton’s The Tyranny of Human Rights here [17].

Barnett doesn’t mention the Third World immigration that started to people the slums of northern England at this time, which is an oversight. In the late 1940s, non-whites started to migrate to the old mill towns, and the negative effects that followed from this are still being felt in the form of grooming gangs and terrorism.

This bureaucratic stifling of industry didn’t only occur in northern England. Modern factories, usually part of an American concern of some sort, were likewise stifled. Managers of a Ford factory in Britain spent months negotiating with the government to expand. Meanwhile, new innovations, such as cranes to load and offload equipment in the ports, were poorly managed. The Labour government insisted on full employment, and as a result stevedores and longshoremen continued to get full pay even though far fewer men were needed. This created an additional manpower crunch for industries that needed the new hires, and generally dragged things down.

The book ends with the outbreak of the Korean War. Britain was faced with its first major international crisis following the Second World War, and it headed into battle with an economy on the brink and a government steeped in late Victorian ideology.

Lessons for America

A large part of the problem was a loss of industriousness on the part of the British workforce at all levels. Again and again, Barnett describes strikes, demoralized engineers, and salesmen representing firms selling new inventions who failed to market their products. Marshall Plan aid was squandered on houses, while the things that actually generated value for the British to build and pay for their homes outright were left wanting.

While the New Deal helped keep American industry sharp, Lyndon Baines Johnson’s Great Society was closer to New Jerusalem. In the late 1960s, American industry was drifting into obsolescence while piles of money were being poured down the rat hole of sub-Saharan uplift and housing projects that were destroyed in Haiti-like fashion over the following decade and a half. While that was happening, piles of money were being spent on the fruitless Vietnam War.

Like their American cousins in the 1960s, the British in the 1940s were being deployed to regions where they won no national benefit. There were far more British troops in the Middle East in the late 1940s than in the vital area of Western Europe. Similarly, it is obvious that today the United States military is involved in pointless deployments in Syria, South Korea, Somalia, and other regions while its border is left undefended while it is swarmed by criminals and desperately poor migrants.

If one is in a hole, as was Britain’s case in the late 1940s and America presently, the first step in fixing the problem is to stop digging.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “Paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

- Third, Paywall members have the ability to edit their comments.

- Fourth, Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected] [18]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

- Fifth, Paywall members will have access to the Counter-Currents Telegram group.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[19]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[19]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.