The Fall of the Neoliberal Order

Posted By Morris van de Camp On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledGary Gerstle

The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order: American and the World in the Free Market Era

New York: Oxford University Press, 2022

Professor Gary Gerstle [2] teaches at Oxford University and has written several excellent books about America and its racial and social problems. One such book is American Crucible: Race and Nation in the Twentieth Century, which was first published in 2001 and was later updated with a few extra chapters describing Black Lives Matter terrorism and some quotes from the cast of non-whites in the Hamilton minstrel show who were mad about Trump being elected.

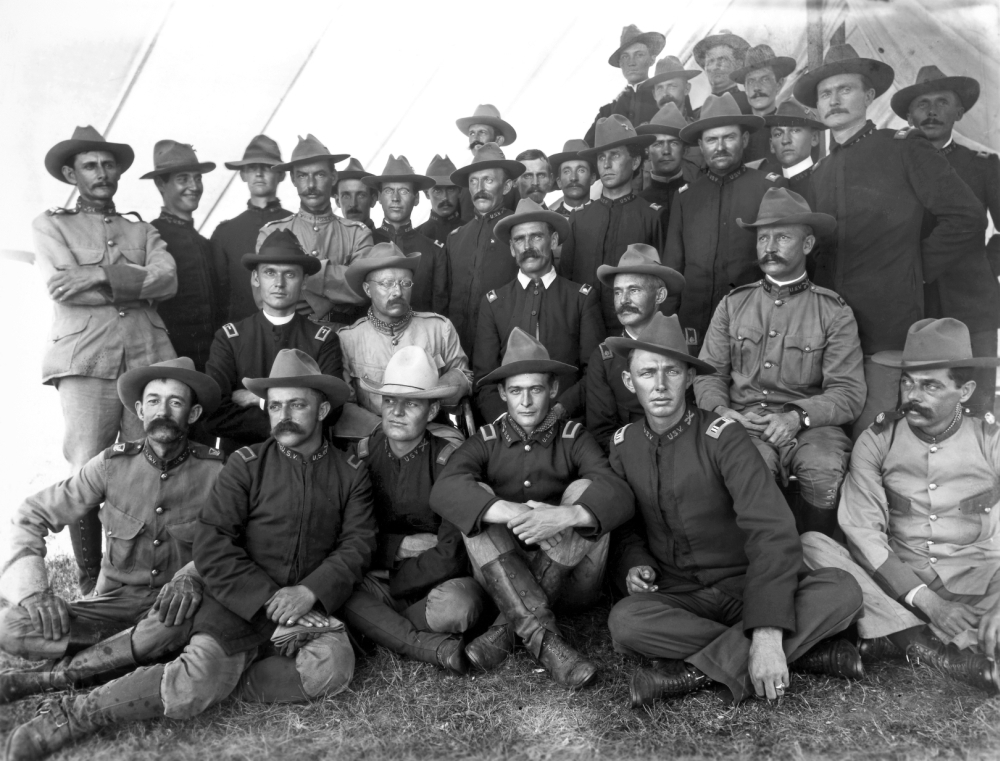

Theodore Roosevelt’s Rough Riders

American Crucible is written from Gerstle’s perspective of a nice white liberal, so it is unsympathetic to calls made presently [3] and in [4] the [5] past [6] for America [7] to become a white [8] ethnostate [9]. It nevertheless excellently shows how America’s founding stock once assimilated European immigrants by using wars [10] of expansion to relieve domestic social tensions, and by integrating the American Majority [11] with European ethnics in the military that fought those wars. Roosevelt’s Rough Riders — the 1st US Volunteer Cavalry — was a multi-ethnic white regiment centered on ethnically American Majority [12] cowboys and pioneers from the West, as well as American Majority [13] patricians from the Northeast. The Rough Riders formed the pattern for the Second World War’s multi-ethnic white platoons, which were so effective.

[14]

[14]The First US Volunteer Cavalry was deliberately designed to put whites of immigrant stock with old-stock pioneer Americans to fight a frontier-style expansionary war in order to assimilate white ethnic groups.

The integration of European ethnic groups was one of Theodore Roosevelt’s projects even prior to the Spanish-American War. Roosevelt’s book Winning the West (1889) argued that America’s westward expansion was a pan-European project, not just an Anglo-American one. Gerstle writes:

All kinds of Euro-American males, even those of foreign birth or immigrant parentage who had never come within miles of a cowboy, would quicken their process of becoming American by imagining themselves as Daniel Boone and Davy Crockett [15], Geronimo and Cochise, Teddy Roosevelt and Rough Rider [16] hero Bucky O’Neil [17]. (p. 41)

Teddy Roosevelt was also an immigration restrictionist. He helped nurture and support increasingly tight immigration restrictions until they were adopted in a form that ended the scourge altogether in the 1920s. Gerstle says that

[t]his movement for immigration restriction strengthened the racialist tradition of American nationalism precisely at the moment when Americans are often thought to have dispensed with “older” notions of racial hierarchy and embraced the freewheeling thinking and behavior of the Jazz Age. Civic nationalism did not disappear at this time; to the contrary, many Americans turned to this latter tradition as a way of defending those who had been racially stigmatized and of reasserting the egalitarian foundation of American life. In the 1930s this turn would culminate in efforts to sharpen assaults on racism. But civic nationalism was not as central as racial nationalism to the 1920s, a time when overwhelming numbers of congressmen and senators voted to make race determinative of the country’s entire immigration policy — and thus to reassert its constitutive role in shaping the American nation. (p. 82)

[18]

[18]The 42nd US Infantry Division during the First World War. This unit was made up of every white ethnic group from nearly every state in the Union. It was deliberately designed to further unify whites in the same way as the Rough Riders, and came to be called the Rainbow Division.

This book goes on to describe America’s sense of itself as a white and Nordic nation in art, the labor movement, film, and the broader culture. The project of unifying America through expansionary wars finally broke apart in the jungles of Vietnam.

Because the book’s perspective is that of a nice white liberal who writes for outlets like The Guardian and the Atlantic Monthly, he misses a few things. He thinks that racism is taught rather than learned. He also doesn’t seem to recognize that integrating sub-Saharans [19] into white military units caused problems for the US military, even though he writes about the problems of “civil rights” and the Vietnam War. Since integration, America’s military has continued to be able to project cruel power, but is ultimately ineffective.

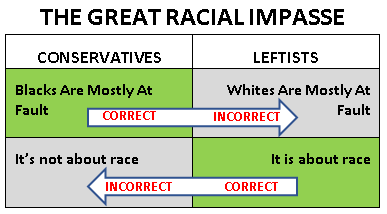

Essentially, American Crucible shows the tremendous accomplishment of America’s WASP elite in absorbing European immigrants in the period between the Civil War and the First World War. Americans cannot absorb non-whites, however. Those racial differences are insurmountable. He makes the liberal racial impasse fallacy [20] in which the Left claims the problem is all about race (correct), but blames whites (incorrect). The best illustration of this fallacy is the Quinn Chart:

[21]

[21]The Quinn Chart shows the great racial impasse that poisons so much of America’s public discourse. Blaming whites for social problems has been the premier narrative in the US since the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

The New Deal

To understand neoliberalism, one needs to grasp what came before it: to put it simply, the economic and social policies of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal. The New Deal was a rational government response to the economic crisis of the time. During the Great Depression, farmers killed livestock and plowed their crops under because the price of those commodities had fallen below the costs of transporting them to market. At the same time, food was in short supply in the cities. Shoe factories stood idle, and people had no shoes. Capitalism had blown a gasket.

The New Deal’s main intention was to use the government to manage capitalism for the benefit of the greatest number of Americans. Government departments were established to manage the economy. Not every decision made by New Deal bureaucrats was a good one, but as the bureaucrats gained experience and industry adapted to the new conditions, Americans pulled themselves out of their hole.

[22]

[22]The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was developed by the FDR administration, but Theodore Roosevelt would have loved it. The CCC was segregated and projects of special importance, such as the Tennessee Valley Authority, hired few blacks. Such reforms in the 1930s were effective because they took race into account.

The New Deal persisted after Roosevelt died in 1945. Harry Truman called his version the Fair Deal. Even the Republican Dwight Eisenhower maintained the New Deal’s essential structure throughout his two terms. This marked the point where government intervention in the economy had become a political ideology which both parties embraced. Presidents Kennedy and Johnson were also avid New Dealers.

It was with Lyndon Baines Johnson that the New Deal paradigm started to hit some snags. FDR had been something of a white advocate. His programs were racially segregated, and he used federal workers to carry out the most important projects, such as building rest stops along the highways and dams to store water for the prairie.

The New Deal was always a clunky government program, and not every policy or project worked as promised. It appeared at first to be a work of genius, after capitalism had collapsed under circumstances of unusual and epic proportions, but as the economy improved, its inefficient use of resources and excessive regulations started to put dangerous pressure on the system, none of which was greater than the policy of uplifting sub-Saharans, especially as Soviet-led propaganda about America’s alleged evil treatment of Africans filtered through to the Third World and the “civil rights [23]” movement gathered steam.

[24]

[24]You can buy North American New Right vol. 1 here [25].

The New Deal worked because blacks were kept on the sidelines during FDR’s four terms. But New Dealer LBJ moved sub-Saharans from the sidelines to the center.

With LBJ’s version of the New Deal, the Great Society, federal money poured into non-white communities and a caste of non-white pseudo-intellectuals and pseudo-elites formed which did nothing but act aggrieved. Shortly after LBJ became President, the illicit second constitution, the 1964 Civil Rights Act, was signed. Sub-Saharans began their well-known pattern of riot and insurgency within hours of the act’s passage.

The Vietnam War didn’t help, either; it went badly. By the late 1960s, many in the Democratic Party saw the New Deal social paradigm as one which encouraged wars of aggression. Then came the 1970s [26]. Years of bad management in American industry, a lack of protective tariffs, the OPEC oil embargo, and the culmination of the great migration of sub-Saharans to the Northern cities destroyed the formerly great manufacturing centers there [26]. The watchword of the 1970s was stagflation — it reflected an economy with stagnation in the form of high unemployment and inflation.

[27]

[27]The catastrophic Democratic Party Convention of 1968 was the beginning of the end for the New Deal’s dominance of the social and political scenes.

The Soviet Threat

Communism’s rise after the First World War was the central event of the twentieth century. Political movements as diverse as fascism [28], American conservativism, and resurgent Islamism were a reaction to Communism.

The New Deal was as much a reaction to Communism as it was a reaction to the Great Depression. In the 1930s, there was a genuine and broadly held belief that Communism would take over the United States by capturing the minds of ordinary workers. One should not discount just how close many Americans actually came to adopting Communism. In West Virginia, for example, striking miners wore red scarves and engaged in gun battles with the police.

And there weren’t only labor problems. The Soviets also gainfully employed skilled Americans. They hired American architects and engineers to create factory towns in Russia from scratch. They also hired American tool- and die-makers to create their manufacturing machines, and moved thousands of Russians to these new towns to work the factories. Soon, they were producing thousands of automobiles. Soviet and Communist industrialization was on the march.

Part of the New Deal’s usefulness was that it genuinely delivered on improvements in living standards for the working class — especially those in a union. The New Deal also mediated problems between labor and capital. Once we had Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt and the New Deal, why jettison that for Eurasian Communism? The American elite of the 1930s and ’40s saw that Communism could change minds, and they worked out a way to change American minds along the lines of their own anti-Communist way of thinking.

By the late 1950s, the fear was that Communism would triumph through Soviet-led military conquest. This helped Republican President Dwight Eisenhower to continue the New Deal, if only for its proven ability to muster, train, and deploy large numbers of troops. The interstate highway system was in fact developed to move troops to potential battlefields and refugees away from cities that were attacked.

Communism also adjusted trade relationships. By 1953, the Communist bloc had taken Eastern Europe, the Soviet Union, China, North Korea, and North Vietnam out of the capitalist trading network. The break wasn’t absolute; the Soviets required grain imports from America to survive, but on the whole the pattern of minimal trade with Communist Eurasia held. On the other hand, the countries of the “Free World” were able to trade with the United States [29] with no trouble at all. By the late 1960s, the factories of America’s Cold War allies were more advanced and their products were better than American factories and products.

The Communists had fallen into deep economic trouble by the 1970s, so they couldn’t make stagflation an issue. Additionally, by the 1980s [30] the unions had as big a hand as management in producing big, obsolete cars that couldn’t compete with Japanese and German imports. The unions were also known to gum up the works with strikes and such. Ronald Reagan broke the unions’ power when he fired striking air traffic controllers, however.

Communism collapsed in Eastern Europe in 1989., and the Soviet Union itself imploded in 1991. China, for its part, adopted a non-Communist economic model at this time. This opened up formerly restricted areas for trade. At first glance, one might suppose that American manufacturers would have made inroads into such areas, but what actually happened was that American capital investments flowed into China.

As, always white advocates predicted what could happen earlier than anyone else. Lothrop Stoddard wrote that [31]

. . . Asia’s industrial transformation is destined to cause momentous reactions in other parts of the globe. If Asiatic industry really does get on an efficient basis, its potentialities are so tremendous that it must presently not only monopolize the home-markets but also seek to invade white markets as well, thus presenting the white world with commercial and economic problems as unwelcome as they will be novel. (my emphasis)

Neoliberalism

In the 1970s [32], neoliberalism came to the fore. It didn’t arise fully formed, but rather began to mature and be propagated during the 1940s [33], when the New Deal was at its height. Nevertheless, it was only after the catastrophes of stagflation and the Vietnam War that neoliberalism started to make headway.

Neoliberalism is a social and economic ideology which prizes free trade and the free movement of capital, goods, and people. It sees deregulation as an absolute good. It likewise holds cosmopolitanism and open borders as positive cultural achievements. Neoliberal ideology regards globalization and diversity as win-win propositions. Neoliberalism’s military applications are examined in the book The Pentagon’s New Map [34] (2004).

Neoliberalism was ascendant during the Reagan administration [35]. As with all large-scale political paradigms, there was a contradiction inherent in it. There was an

uneasy coexistence within the neoliberal order of two strikingly different moral perspectives on how to achieve the good life. One, which [Gerstle] label[s] neo-Victorian, celebrated self-reliance, strong families, and disciplined attitudes toward work, sexuality, and consumption. (p. 12)

This protected an individual from market excess and poor choices regarding sex, drugs, and alcohol that were easy to make in an environment of free markets and deregulation.

Neo-Victorian attitudes were supported by Gertrude Himmelfarb and her husband, Irving Kristol. Such ideas also gained a following through Jerry Falwell [36] and the Religious Right [37]. Neo-Victorian attitudes likewise got a boost because the communications industry expanded by means of cable, satellite, and the Internet. In response to this leap in technology, the government deregulated the industry, and most critically,\ ended the “fairness doctrine [38].” The end of the fairness doctrine was partially a response to a resurgent American Right that grew in no small part due to the obvious problems of the “civil rights” movement, which was wholly supported by the establishment and mainstream media.

The other moral perspective within neoliberalism is “cosmopolitanism”:

. . . a world apart from neo-Victorianism. It saw in market freedom an opportunity to fashion a self or identity that was free of tradition, inheritance, and prescribed social roles. In the United States this moral perspective drew energy from the liberation movements originating in the New Left — Black Power, feminism, multiculturalism, and gay pride . . . (p. 13)

It was during the Clinton administration [39] when it became clear that neoliberalism had become the dominant social and political force. Clinton reaffirmed neoliberalism as President, although that ideology had been pioneered and advanced by his opposing party. Clinton’s embrace of neoliberalism was not unlike Eisenhower’s earlier embrace of the New Deal.

Part of the reason why Clinton was able to embrace neoliberalist policies was because the New Left believed in many neoliberal ideas as well:

The New Left’s engagement with neoliberal principles can be discerned in the vehemence of its revolt against what it regarded as the over-organization and bureaucratization of American society resulting from New Deal reform and in the desire to multiply the possibilities for personal freedom. (p. 8)

The points of overlap between the Left and Right regarding neoliberalism came down to three points. Two of them were metapolitical:

- The novels of Ayn Rand.

- Murray N. Rothbard’s journal Left and Right: A Journal of Libertarian Thought, launched in 1965. (The year it started is critical. The New Deal died because of “civil rights.” By 1965, sub-Saharan rioting and crime was the truth that no polite American could name.)

- The tech revolution in Silicon Valley and elsewhere. Tech engineers were fired as a result of New Left ideas and New Age spiritual beliefs.

The Culture War and the War on Terror

The vicious political battles of the culture war during the 1990s were fought between President Clinton and Congressman Newt Gingrich, but they masked considerable cooperation between the parties on economic policy. They worked together on keeping the borders (mostly) open and tariff protections toothless. They also deregulated the financial industry.

Investment banking was mixed with commercial banking. Lenders packaged mortgages into larger packages and sold them in massive bunches. There was a push to refinance home loans using adjustable rate mortgages and interest-only loans. From top to bottom, the American economy grew awash in bad debt, but for a time that calamity was merely a cloud the size of a man’s hand. It would soon be obscured by the dust clouds of the collapsed Twin Towers.

Gerstle doesn’t point out the obvious fact that “civil rights” and neoliberal ideology helped set the stage for 9/11. Had the immigration restrictions of the 1920s still been in place, and had white ticketing clerks, immigration officials, and law enforcement agents been free to deal with non-white troublemakers, there would have been no possibility of an attack. Additionally, neoliberalism encourages the mixing of people, so Islamic fanatics plotting death and destruction are merely part of the neoliberal package.

After 9/11, President Bush decided to invade Iraq. The initial military conquest worked well enough, but there was no plan to reconstruct Iraq in any meaningful way. The neoliberal Bush regime simply presumed that the socialistic structures put in place by Iraq’s Ba’athist leadership had been inefficient, and they were done away with — but nothing took their place. Iraq’s economy crumbled under the neoliberal occupation, and unemployed Ba’athists went on to fight an insurgency and a sectarian war.

A Rainbow Nation of Homeowners and the 2008 Economic Collapse

Bush II won by the narrowest of margins in 2000, hinging upon election shenanigans in Florida. What would have happened had Gore won in 2000? President Gore would have reacted to 9/11 in the same way that Bush did: by invading Afghanistan. But President Gore wouldn’t have been burdened by Bush Sr.’s decision not to go all the way to Baghdad during the Persian Gulf War [40] of 1990-1991, so it is possible that there would have been no Iraq War at all. Nevertheless, President Gore would have very likely made the exact same decisions that Bush did which in turn led to the 2008 economic collapse.

Clinton’s deregulation of the financial industry was continued by George W. Bush. He was a color-blind neoliberal who encouraged sub-Saharan and other non-white borrowers to obtain enormous loans [42] in order to purchase houses. Bush thought non-whites [43] would become wealthy because their houses would increase in value.

Bush should have listened to the race realists. The non-whites defaulted on their loans and the economy unraveled. This disaster allowed the mixed-race Obama to easily win the presidency. He came to office on the promise that he would be a transformative president. Economically, he was nothing of the sort. He was as much a neoliberal as his predecessors. His ideas to fix the economy hinged upon saving Wall Street while Main Street failed. This led to the first anti-neoliberal movement: the Tea [44] Party [45], which was made up of color-blind American Majority whites who were implicitly “taking their country back” from non-whites, but explicitly were protesting the neoliberal bailout plan. Shortly thereafter, the Left countered this with the Occupy Wall Street movement.

The 2016 Political Revolution

[46]

[46]You can buy Greg Hood’s Waking Up From the American Dream here. [47]

The Tea Party captured a segment of the Republican Party, but the Occupy Wall Street movement went nowhere. It had no charismatic leaders, no list of demands, and no coherent plan to navigate America out of the mess it was in. Both the Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street had enormous ideological crossover, however. This was clear during the 2016 election. The campaign began with Crooked H as the establishment candidate who was favored to win, but she had a very difficult time winning the Democratic Party’s primary. Her rival, who represented Yankee Vermont, was a Jewish socialist who was out of step with the mainstream organized Jewish community. Gerstle argues that Sanders diverted non-white support from Crooked H. I don’t recall seeing this at the time; rather, Bernie [48] Sanders [49] gained support from Leftist American Majority whites [50]. Crooked H had non-white supporters who were ultimately unenthusiastic.

Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump were remarkably similar. Both were from New York City’s outer boroughs. Both were against neoliberalism hollowing out the economy, and had been against this trend since the 1980s. Neither supported free trade or immigration. The only real difference was that Trump was alleged to be sympathetic to White Nationalism.

[51]

[51]During the 2016 presidential election, it was whites who felt the Bern. The Sanders and Trump campaigns had many crossover ideas.

Gerstle argues that Trump as President was a great entertainer, but tended not to follow up on most of his ideas, and many of his schemes were poorly planned and executed. Trump had a terrible time working with Congress. He also had difficulties with the government’s various departments. He was unable to use state power to bring down his rivals. He was also saddled with an establishment that enabled the Black Lives Matter (BLM) insurgency during 2020’s Summer of Floyd.

Gerstle believes that BLM was likewise a reaction to neoliberalism’s tendency to imprison sub-Saharans. I don’t agree. I think that BLM was organized no differently from a State Department-funded color revolution abroad. Additionally, by 2012 the Democrats recognized that hyping a racial incident could bring sub-Saharans to the polls. “Civil rights” destroyed the New Deal, but under neoliberalism, which encourages the free movement of people, “civil rights” got an extended life. Mass incarceration is a manifestation of the contradictions within neoliberalism. One can have non-whites running around everywhere under neoliberalism, but sub-Saharans are prone to violence and crime, so you need to lock them up; otherwise, neoliberalism cannot function. Wall Street traders don’t like getting mugged, after all.

Trump lost in part because of his failure to deliver on a number of promises. Gerstle doesn’t believe that there was election [52] fraud in 2020 [53]. Now America has a formerly neoliberal President who is elderly and senile. There is no new economic, political, or social paradigm that Americans can embrace, although it is clear that Sanders’ and Trump’s ideas had a great deal of overlap and drew supporters from the American Majority [50].

Gerstle views America as torn between the socialist Left and the authoritarian Right for the time being. For my part, I don’t want to see an authoritarian Right; I want a just, ethnonationalist country based upon the American white ethnic group.

Gerstle does, however, show a clear path for white advocates to take as we seek a white American ethnostate:

Establishing a political order demands far more than winning an election or two. It requires deep-pocketed donors (and political action committees) to invest in promising candidates over the long term; the establishment of think tanks and policy networks to turn political ideas into actionable programs; a rising political party able to consistently win over multiple electoral constituencies; a capacity to shape political opinion both at the highest levels (the Supreme Court) and across popular print and broadcast media; and a moral perspective able to inspire voters with visions of the good life. Political orders, in other words, are complex projects that require advances across a broad front. New ones do not arise very often; usually they appear when an older order founders amid an economic crisis that then precipitates a governing crisis. “Stagflation” precipitated the fall of the New Deal order in the 1970s; the Great Recession of 2008–2009 triggered the fracturing of the neoliberal order in the 2010s. (p. 2)

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “Paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

- Third, Paywall members have the ability to edit their comments.

- Fourth, Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected] [54]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

- Fifth, Paywall members will have access to the Counter-Currents Telegram group.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[55]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[55]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.