Four Flags Over Alabama:

The Strange & Marvelous Career of a Confederate Raider, Part 1

Kathryn S.

5,576 words

Part 1 of 2 (Part 2 here)

Prologue: The “Alabama Claims”

Sir Alexander E. Cockburn, official of Her Majesty’s Empire, couldn’t wait for the Conference to end.[1] The Geneva setting was picturesque: Tourist treks to the “High Alps” had just closed for autumn, and as the first snows began to fall on the upper châlets, peasants drove their cows and goats

from the heights to the softer slopes below. But Sir Alexander wasn’t there to bask in the rustic scenery. He had come to represent British interests in an international dispute whose roots dated back to a decade earlier.[2]

The days’ meetings with the crusading American diplomats seemed interminable. If the British thought that the American Civil War had ended in 1865, they soon learned otherwise. Years after Appomattox, Sir Alexander’s country found itself embroiled in a legal battle with the American government that rivaled the actual war in its bitterness — hence his reluctant presence in Switzerland.

According to the United States, the British had violated their neutrality during the Civil War by aiding “Rebel” forces and building “Rebel” ships; not only that, but many of Her Majesty’s subjects had defied their own legislation that forbade the raising of armies and arms on British soil for the purpose of fighting in foreign wars. “Foreign Enlistment Act, 59 Geo. III, cap. 69,” to be precise, American lawyers helpfully pointed out, as they quoted chapter and verse of Britain’s own laws that the United States planned to use against it.[3]

Central to the issue at hand was the lingering ghost of the (in)famous Confederate sloop, the CSS Alabama — Boogeyman of the Seas, “Naval Beast of Prey,” that “Villainous Shark of the South.” For two years the Alabama and her crew had circled the deep like a dreaded kraken on the prowl, destroying any Yankee merchant craft that wandered into her sights. By 1864 she had sunk and/or burned nearly 70 vessels, boarded scores more, confiscated cargo of tons beyond count, and caused tens of millions of dollars in damages. And who was responsible for the Alabama’s “depredations”? Why, her creator: Perfidious Albion.

In support of their case, Americans gathered a dossier of evidence dating back to 1863, blandly titled: “The ‘Alabama’: A Statement of Facts from Official Documents.” It began with a quotation from lady-moralist Harriet Beecher Stowe, hardly a knowledgeable, much less “official,” source of “facts.” But then, she was prone to writing on subjects about which she was completely ignorant.[4] In that mushy-headed tone of hers, she railed:

Yes, we have heard on the high seas of a war-steamer [the Alabama], built for a man-stealing Confederacy with English gold in an English dockyard, going out of an English harbor, manned by English sailors, with the full knowledge of English government officers, in defiance of the Queen’s proclamation of neutrality.[5]

You can buy Tito Perdue’s novel Cynosura here.

The remainder of the screed went on to declare the Alabama’s “mode of seizing and burning merchant vessels on the high seas . . . [to be] something so new in warfare” — as if privateering practices weren’t as old as the seas themselves — “that this alone would have rendered her an object of deep interest, if not positive aversion, in all maritime nations.” For too long the Alabama and its “pirate” Captain had “destroy[ed] the property of the American people, with whom England [was] at peace, and with regard to whose conflict . . . she [had] declared herself to be neutral.”[6] How many hours had Sir Alexander endured that drumbeat in recent days?

Working themselves up into an indignant lather, United States representatives further accused the British of the “most gross dereliction of duty,” especially “on the part of subordinate officials”; of “culpable laxity” and “neglect,” if not outright “complicity with the enemies to the American people.” Most importantly, by aiding the Confederates and thus “their doctrine of slavery,” the Britishers made themselves “enemies to the whole human race.”[7] The Americans at first sought reparations that amounted to an outrageous two billion dollars — or, barring that, the ceding of Canada. Out of the sorry litigious affair, the Geneva Arbitration Court came into being and the British were forced to pay their Anglo cousins millions of dollars in damages. The determination and fury of this legal struggle were of such a pitch that it seems likely to this author that the British were not the sole targets of Northern wrath. Years after the Alabama’s demise, the Yankees were trying to sink her again. Once was not enough.

In contrast, I propose to resurrect the Alabama in this essay, which has three aims. The first is to tell a story about a ship and a people who were proudly conscious of their whiteness and defiant in the face of liberal moralism; the second is to explore the treacherous waters of “neutrality,” and how fuzzy that status can be — how it openly declares, as much as it hides, state interests; and lastly, to make clearer the link between the Civil War and modern globalism. Peer beyond the thickets and battlefields of Virginia, where our minds most often roam when imagining that conflict, and look to the oceans. There, one will see how both North and South used the Alabama to pitch their global appeals for their nationalist ends. When making their case abroad, Northerners were more likely to use universalist language: The Alabama committed “crimes against the civilized world” and “crimes against humanity”; she was the “enemy of free commerce” everywhere, not to mention she served the diabolical interests of “the Slave Power” and its “man-stealing,” which was surely the blackest sin in all of human history. At Geneva, federal statements like those “invented new rules . . . not previously included in the code of international law.”[8] Their arguments laid the groundwork for twentieth-century supranational bodies, including the likes of the League of Nations and its successor, the United Nations.

The South, on the other hand, made its foreign bid in more particularist language that affirmed national, or local sovereignty: They sought aid “for the preservation of the States,” “for the good of the Southern people”; the Alabama sailed for “the Southern Cause,” to break the blockade along the Southern coasts, to support “the brave Johnnies” in gray, and so on. Even if most of her crewmembers were European (her officers were American Confederates); even though she never once docked at a Confederate port; even as she sailed under four different flags during her “lifetime,” and then after her “death,” it was clear to her Confederate champions that her mission was always and ever a Southern one.

And yet, for all this patriotic talk, and for all the renown that the steamer won for herself around the world, none of it achieved recognition for the Confederacy. The Alabama’s career is a credit to white history, but her tale is as cautionary as it is brilliant.

A London Punch cartoon from January 20, 1872: Uncle Sam, the American windbag, seeks to score political points for the upcoming election, and hands British John Bull reparations demands with bogus reasons attached to the bills: “Want of Sympathy,” “Moral(e) Damage,” “Prolonging of War,” and “Southern Proclivities.”

Part I: Under the Union Jack[9]

As any American statesman serving at the time of the Napoleonic Wars could attest, neutrality was a difficult position for a young nation to take. It was a legal decision that demanded not passivity, but an active defense of its posture in the face of flagrant British and French violations of its sovereign status. Sailor-impressment, thievery, and diplomatic bullying were the orders of the day. Decades later, during Mr. Lincoln’s War, the French and especially the British found themselves facing a reversed situation: Two American belligerents sought to draw them into the fray, despite European protestations of disinterest.

When they weren’t outraged by British or French machinations, Americans had observed the conflicts in Europe with an often poorly-concealed voyeurism. Thank goodness they had escaped the ancient, but petty, rivalries of the Old World, they sniffed, content with the oceans between them. Having moral superiority did not, however, mean that a man couldn’t take an interest in foreign squabbles. At the start of the Crimean War, an editor of the Wilmington, North Carolina Daily Journal complained that “there they [Turkey and Russia] have been all summer and fall, grumbling and spitting at each other like belligerent ram-cats, with England, France, and Austria holding them back by their respective tails.” Though bien-pasants had pronounced war “‘inevitable’ any time for the last several months . . . there hasn’t been a lick struck yet.” The subject is getting dull, the writer lamented, “and we are ashamed to present it anymore to our readers . . . On behalf of all newspaperdom we demand a fight — something to keep up the excitement . . .”[10] Soon, this American journalist would get “excitement” aplenty, lashed in his turn to the press of Fortune’s meat-grinding wheel.

The “Anaconda” vs. “King Cotton”

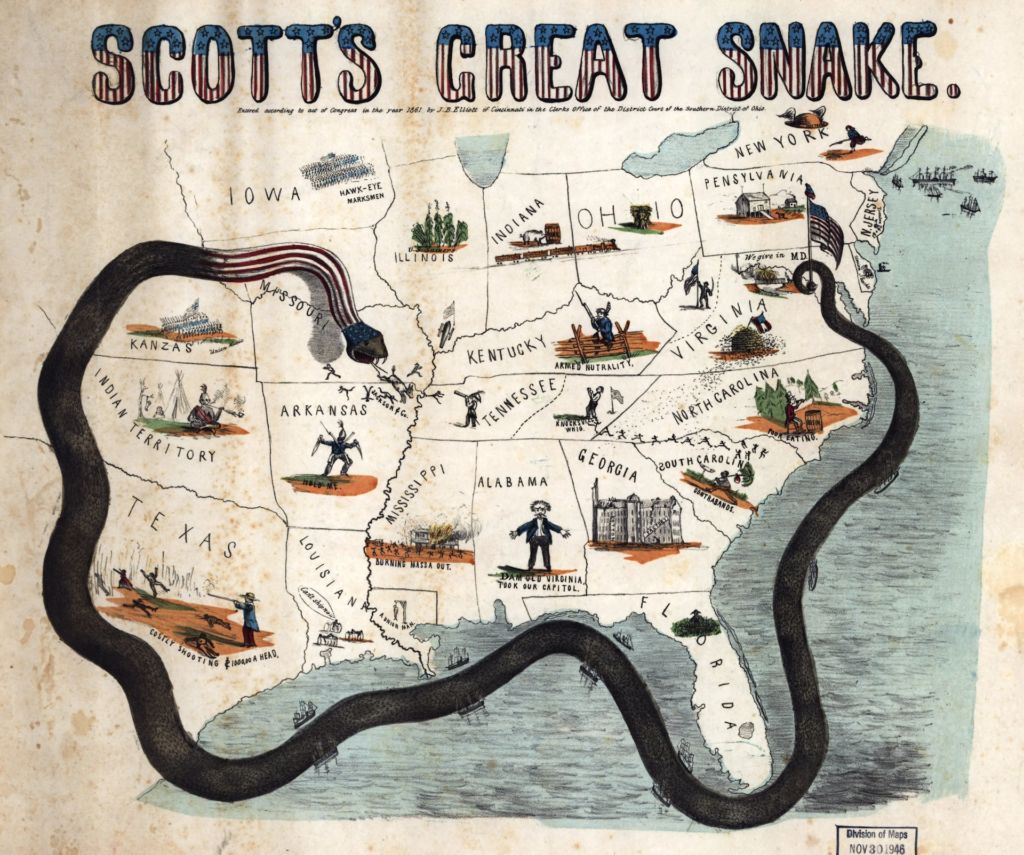

It was indeed excitement that prevailed in early 1861, as 11 Southern states declared themselves members of a new Confederate nation and the old Union dissolved. But the South had virtually no navy with which to counter the North’s 7,600 sailors, 70 warships, and large merchant marine (fleets that would only become larger and more ferocious as the war progressed). Southerners had bitten off more Johnny-cake than they could chew. Cognizant of the Union’s advantages in shipping and manufacturing, General Winfield Scott, too old and fat to reprise his role as overall commander of US forces, nevertheless devised the best Northern strategy of the war: the “Anaconda Plan.” Union warships positioned themselves at all Southern ports in order to strangle the Confederacy’s economy and cripple the South’s ability to wage war.

The blockade would pay ever-greater dividends with each year that the conflict dragged on, but one Richmond lady noticed its consequences immediately: “The effects of the blockade were very early felt . . . between the extraordinary influx of population” that streamed into the capital from the countryside, “and the existence of the blockade . . . [Virginians] were compelled to submit to the vilest extortions by which any people were ever oppressed.” Prices on goods of domestic manufacture increased first, then “cotton and woolen fabrics soon brought double prices.” In place of imported teas, the costs of which had inflated dramatically, Southerners used “the leaves of the currant, blackberry, willow, sage, and other vegetables.” When sugar grew scarce “and so expensive that many were compelled to abandon its use altogether, there were substituted honey, and the syrup from sorghum.” All of “the numberless and nameless articles for which [they] depended upon foreign markets were either to be dispensed with or to be manufactured from [their] own industry and ingenuity.”[11]

You can buy K. M. Breakey’s Shout: The Battle Cry of Freedom here.

It was this forced “ingenuity” that resulted in the almost navy-less Confederacy pioneering much of the technology used in modern naval warfare, including some of the first functional ironclads, submarines, and torpedoes. Additionally, Scott’s blockade seemed to promise another silver lining: If Southerners could ship no cotton to the textile-hungry mills of England and France, then those powerful countries might shake off their neutral stupors and force the Yankees to end the war in a treaty that recognized the Confederacy as a sovereign nation. After all, trading interests and embargoes had caused more than one war in living memory.[12] This was the essence of “King Cotton Diplomacy,” a term coined by South Carolina Senator James Henry Hammond in 1858. “What would happen,” he asked his countrymen, if we furnished no cotton “for three years?” It was all but certain that “England would topple headlong and carry the whole civilized world with her, save the South. No, you dare not make war on cotton. No power on earth dares to make war upon it. Cotton is king!”[13]

And indeed, there began to appear in English newspapers calls for charity and advertisements for organizations: “The Cotton Districts Relief Fund,” and “Relief of Distress in Lancashire,” where shut-down mills had plunged already poorer populations into extreme poverty.[14] Out of this region’s suffering there came mournful tunes, like “Th’ Shurat Weaver’s Song”:

Confound it! I ne’er wur so woven afore . . . we’n suffered so long thro’ this ‘Merica war, ‘At there’s lots o’ factory folk getten t’ fur end, An’ they’ll soon be knocked o’re iv these toimes doesn’t mend. Oh dear — iv yond Yankees could only just see Heaw they’re clammin’ an’ starvin’ poor weavers loike me, Aw think they’d soon settle their brother an’ strive To send us some cotton to keep us alive . . .[15]

To Southerners it appeared more and more likely that Britain would intervene, if only to prevent an economic disaster. And then, wonder of wonders, the North blundered into a situation that seemed designed to provoke the British.

The “Trent Affair”

The North had worse relations with the British throughout the war, starting with the infamous “Trent Affair.” In early November 1861, the British frigate Trent left Havannah, then proceeded toward the narrow stretch of the “old Bahama Channel.” Early the next day, a lookout informed the Trent’s Captain Moir that a steamer bearing no colors had materialized ahead and appeared to be waiting for them. Cautiously approaching the mystery vessel, Moir raised “the British ensign,” only for the stranger craft to hoist the American flag and fire a live shot across the Trent’s bow. This aggression was “quite contrary to all acknowledged law,” but the Trent continued her course until another volley from “a long pivot gun on the Americans’ deck” burst 100 yards away.

Having thus persuaded the Trent’s crew to stop their progress, a party of the Americans rowed toward them in a boat “containing two officers and about 20 men, armed with muskets, pistols, and cutlasses.” Shoving off and boarding the Trent, the perpetrators revealed that they crewed the US warship San Jacinto. Their purpose was to arrest two “traitors” who had booked passage on the Trent (Confederate commissioners John Slidell and James Murray Mason). Moir refused to give them a list of his passengers, arguing that they sailed “under the protection of the English flag.” The Americans seized Slidell and Mason anyway. Before the raiding party could leave with their captives, an outraged Trent commander thundered, “In this ship I am the representative of Her Majesty’s Government, and I call upon [everyone] . . . to mark my words when . . . I denounce this as an illegal act . . . of wanton piracy, which, had we the means of defense, you would not dare to attempt.” The general “indignation felt on board the British vessel by every person, of whatever nation, can better be imagined than described.”

After news of the outrage reached Parliament and the British public, more than a few reckless men urged a declaration of war to “redress the insult [made] to the British flag.”[16] The US narrowly avoided a sequel to the War of 1812 in those final weeks of 1861. Though the “Trent Affair” was a harebrained and dangerous stunt, the Union had cause to fear a Confederate association with Britain.

The Alabama’s English Berth

Whether the reason was bitterness following the “Trent Affair,” Union threats to invade Canada, the blockading of an important trading partner — or if it was the simple willingness to allow private enterprise to supply a market demand — the British government chose not interfere in Liverpool’s booming business of building ships for Confederates. According to the Laird Brothers, owners of the company that made the craft later called the Alabama, they had entered into the contract to build her[17] “in the usual course of [their] business.” After all, their “firm [had] . . . for upwards of 30 years been in the habit of building vessels of war for [their] own Government, for foreign governments direct, and for the agents of foreign governments.”[18] Their 2,500 employees labored on her in broad daylight and under the inspection of countless visitors, so convinced of the project’s legality were they.

And when the Laird Brothers had finished their work, the ship was a glorious sight. Two forms of combined energy made her an especially swift sea-glider: massive sails to catch the breezes, and a coal-driven steam engine. Initially dubbed the “290” for her dockyard number, the sloop was 211 feet, 6 inches long; 31 feet, 8 inches across; 17 feet, 8 inches in depth; and she weighed over 682 tons. When American agents in England caught wind of her existence and imminent departure, they submitted to “Officers of the Crown” a flurry of requests to detain her. Several days, however, “were allowed to elapse” before those officers acted, the delay caused by a supposed and “sudden malady” that “totally incapacitated” the Queen’s Advocate, rendering him “unable to conduct” his duties in a timely fashion.[19] On July 29, 1862, authorities finally ordered the ship’s seizure . . . but that very morning she had sailed from Liverpool and beneath the British colors. For the first, but far from the last, time, she had slipped through Yankee fingers and vanished into a blue horizon whose vastness strained all imagination.

Meanwhile, hundreds of miles away and in the Portuguese Azores, a dashing ex-US Navy Captain was waiting for her.

Part II: Under the Stars and Bars

Captain Raphael Semmes was a handsome and well-educated native of the Maryland coasts, the perfect boyhood environment in which to develop an enthusiasm for the Navy. Among the first areas settled by Britons in colonial America, the Chesapeake Bay of Semmes’ boyhood was carved with capes, cliffs, and inlets; scored by islands, and rivers great and small. Some 35 million years ago, a meteor impact blasted a large crater off the Delmarva Peninsula, and rising water levels after the last Ice Age submerged much of the region, along with the nearby Susquehanna River Valley. It drew colonial ships into its unique mazes of shoals and lagoons, where passengers disembarked and settled. Thus, its place names boasted those of some of the oldest English families, and its coasts nurtured some of the oldest English loves: the lure of the sea and the dream of the sail.

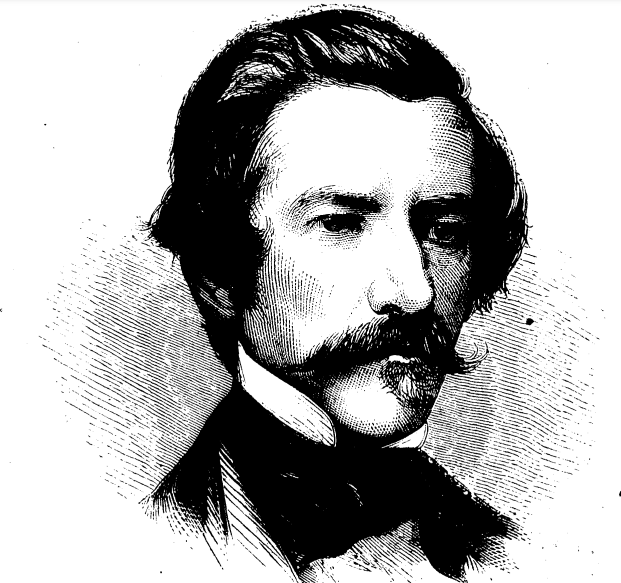

So it was with young Raphael Semmes. In 1826 he graduated from the Naval Academy at Annapolis and began his career as a midshipman, achieving his lieutenancy in the 1830s. Contemporaries described him as “excitable, energetic, and daring in nature . . . slim [and] quick in his movements.” At that point, he “lived the routine life of all naval officers,” one of long and often lonely periods at sea, punctuated by layovers in foreign ports.[20] If the work was at times “routine” — the same sort of labor-intensive activities had to be repeated every day, the same sort of scenery and faces viewed for weeks at a time — it also rewarded men with unusual adventures.

The outbreak of the Mexican War (1846-48) torpedoed American naval “routine” in a major way, spurring the growth of its smallish military and affording opportunities for officers to distinguish themselves. For his part, Semmes proved to be a brave and talented leader “both on land and sea,” serving with the Naval Battery in March of 1847 at the siege of Vera Cruz, and at the subsequent battles of Churubusco, El Molino del Rey, Chapultepec, and San Cosme Gate.[21] Finally, he accompanied the Army on its march and capture of Mexico City.

For Semmes, it had been a “splendid little war,” and for a time it quenched his thirst for the transient life of a sailor. Afterwards, he settled with his family in Mobile, Alabama, where he practiced his other craft: the law. But even as he devoted himself to a new career, he kept the blinds drawn back and the windows of his Mobile offices open so as to breathe that indescribable and complex smell of the surf salt, to catch on slow afternoons the swooping keens of the gull cries, and to remember.

In February of 1861, the Boston Daily Advertiser spared a single line for him when it reported that “Commander Raphael Semmes, now of [the state of] Alabama, has resigned his commission in the Navy.”[22] It would be the last time a Yankee newspaper would ever mention him with such equanimity.

“It’s that — d Pirate Semmes — the Ship Is Lost!”

When the “290” left England in the closing days of July, she picked up 50 hands off Point Lynass, then continued on to the Azores, where she weighed anchor in Portuguese waters. While there, she met another vessel named the Agrippina, whose crew had arrived from the Thames. The men offloaded from the latter onto the former several artillery pieces, stores, round shot, and canister. Soon afterwards a third vessel, the Bahama, approached the two parties. From this last ship, the recently commissioned Confederate naval officer Captain Raphael Semmes boarded the “290,” bringing with him an entourage of more men and supplies.

Before nightfall, Semmes gathered the crew and with a flourish produced a letter from President Jefferson Davis. The “290” would be no ordinary ship, he revealed, and its men would perform no ordinary mission. All hands willing would pledge themselves to ruining Yankee “commercial interests” for as long as the Lincolnites continued to blockade Southern coasts — old-fashioned pillage for a worthy Cause. And, Semmes continued, the pay received coupled with the spoils captured, would enrich all who swore an oath to faithfully serve the Confederacy on this, the newly christened steamer, CSS Alabama. “Aide Toi et Dieu T’Aidera [God Helps Those Who Help Themselves],” was its motto. Overhead, the British flag was lowered, and in its place rose the Stars and Bars. Though most of the sailors were English, Irish, Scottish, and a smattering of Frenchmen, they agreed to share in the South’s destiny with enthusiasm and never looked back.

By mid-September of 1862, Semmes and the Alabama had become newsworthy, the story-grist for British journalists to speculate about an overseas conflict in the same manner that Americans once had about the far-off Crimea. Led by “the renowned Captain Semmes,” the “man-of war lately from Liverpool will be” sure to cause a splash, one author for the London Times wrote slyly. We may “expect soon to have the accounts of the war varied by details of an action at sea.”[23] Of “action” and of controversy, the Alabama would more than deliver.

That same month, Captain Hagar of the merchant ship Brilliant, sailing from New York to London, “was accosted by a steamer that fired a gun” across his bow. At the same moment, the marauder “display[ed] the Confederate flag.” It was the Alabama with vengeance on her mind. A detachment of Semmes’ crew ordered Hagar “to get in a boat” and to bring with him “the ship’s papers.” When Hagar came aboard as commanded, he was met with the captive crews of several other victim-vessels: New England whalers, whose harpooning the Alabama had “interrupted.” After confiscating Brilliant’s cargo, the raiders “set her afire.” Around 7 PM, “she was engulfed in flames and continued to burn all night.”[24] Another nearby American bark, lured by the wicked blaze against the black, assumed that the doomed ship’s crewmen must have been in distress. But no sooner had the would-be rescuers arrived on the scene when they, too, were attacked and taken prisoner.

You can buy Georges Sorel’s Reflections on Violence from Imperium Press here.

The Northern press was aghast. The “unconscionable” action, violating samaritanism on the seas, “[could] only be characterized as a crime against humanity and an offense contrary to the universal sentiments cherished by the civilized world.”[25] Perhaps a more immediate and sharper consequence was the fortune Northern businessmen lost that day. Among the Brilliant’s destroyed cargo were six barrels of flour; 30,456 bushels of wheat; 43 tierces of beef; 26 barrels of pork; four casks of Zinc-oxide; 27,424 pounds of tallow; 19,956 pounds of butter; 8,043 gallons of cocoa; 12,200 pounds of bacon; and large quantities of pork heads and staves.[26] At this rate of theft and with this kind of British “neutrality,” one Boston wit surmised, “we shall not be surprised to hear” by next week that “the ‘British and Southern Joint-Stock Association for Sweeping the Seas’ has opened offices in Liverpool and London.”[27]

By the end of October, Semmes and the Alabama men had carved yet more notches into the ship’s wooden masts. Their exploits “have excited great alarm in commercial circles,” a Londoner remarked, and “the rate of insurance on all American ocean-going vessels has been raised 5 per cent today by the published reports of [Semmes’] achievements.” If his activities continued, “the certain result [would] be . . . to throw all the European and a large portion of the Asiatic trade of America into British and other European bottoms.” Northerners no longer printed Semmes’ name without the sobriquet “pirate” in front of it. A “loud and rather angry demand [was] now being made upon” the US government. Its Navy needed “to fit out an expedition” without delay and with the sole aim of intercepting the Alabama, “hang[ing] [her] captain, and convert[ing] the ship to [Northern] uses.”[28] Conversely, elated Southerners took great pleasure in each of the Alabama’s exploits. They praised the wily captain and the ship that made continual fools of the overconfident and overbearing Federals. Songwriters dedicated rousing verses to their feats: “Roll, Alabama, Roll,” the “Sea Kings,” and “Vikings of the South,” who followed in the proud ancestral footsteps of those heroes at Salamis, Lepanto, and Trafalgar.[29]

The crew, too, basked in their growing notoriety. A petty officer serving on the “celebrated vessel” wrote that he had “tak[en] well with . . . ship, captain” — whom they called “the Admiral” among themselves — “and cause . . . no crew could be more comfortable . . . plenty to eat, plenty to drink, and plenty of work to do, is the order of the day.” Since the summer, the Alabama’s men had installed additional guns and welcomed more “brave volunteers.” He claimed that it would be an “endless task [relating] the fearful havok” he and his comrades had sown amidst the terrified Yankee merchantmen; impossible to tell in full detail the “destruction of the many splendid ships, of which not one plank [we] left fastened to another.” They had already taken 20 vessels “laden with every kind of article which it [was] possible almost for the countries of the world to produce.” And all of it, along with the ships themselves, they destroyed, excepting “one or two,” whose commanders gave Semmes bonds “payable to President [Jefferson] Davis.” The Tuscarora was the latest vessel they had allowed to go relatively unmolested, because it “had a large number of females as passengers, [whom] the skipper said could not be stored in our ‘fixins’ . . .” The character of Semmes and “the historical chivalry of the South would not permit” such a thing. Still, as the Tuscarora slid out of sight, the Captain “declared that it was enough to break a man’s heart . . . to part in such a way with so splendid a ship.”[30]

The Manchester, on the other hand, had not been so lucky. As it cruised the chilly autumn waters one afternoon, its first mate “stated that all on board his ship seemed in good order”: just another day at the helm. As he began to doze off to the flux of the waves, he heard the alarm bell ring. “A sail!” the lookout cried. The “red cross of St. George was flying” over the mysterious barge. “‘There’s a British man-o-war bearing down on us!’” At that instant, “down went the British ensign, and in its place appeared the full flag of the Confederates.” Accompanying the bait-and-switch, cannon fired “a 10-pound shot right across the bows.” The Manchester’s captain gaped in astonishment. After a “repeated survey” through his glass, he went livid and exclaimed, “It’s that — d pirate Semmes — the ship is lost!” A scant two hours later, every crewman, from the Captain to the cook, were prisoners on board the Southern privateer. The last Alabama’s petty officer saw of the Manchester “was a bright sheet of fire [on] the horizon line as darkness fell.” Perhaps the only thing better than spoiling Yankee commerce, he mused, was “hearing news about ourselves.”[31]

Northeastern seaboard communities were less pleased. In an article ironically entitled “The Southern Blockade of New York,” the author referenced a clipper ship, the Dreadnaught, that had arrived the previous day in New York from Liverpool. The trip had been costlier, more dangerous, and much slower, since its Captain had felt obliged to make “a long detour to the northward to avoid the attentions of Captain Semmes and the rebel steamer Alabama.” It is “humiliating for us to chronicle such a feat as this,” he groused. Whereas they had “been blockading Charleston and Savannah by fleets at the very mouths of [Southern] harbors for 18 months with the grand net result of sending into these ports more foreign steamers than ever entered before,” the Confederates had succeeded in “so thoroughly blockading New York by a couple of [ships] . . . as to compel” ordinary transatlantic commerce to coast the icy shores of Greenland for safety. For all its improvements of late, the Navy Department had been “utterly out-classed.”[32] The “Pirate Alabama” continued to trawl the waves “under its nose.”[33]

Pining for better sport and a milder climate as the New Year approached, Semmes and the Alabama sailed south to the Gulf of Mexico. He planned to “strike a blow” at US General Nathaniel Banks’ expedition, then preparing for an invasion of Texas. Though a “prominent Massachusetts politician,” Banks had “no sort of military talent,” Semmes scoffed. Through nepotism and the power of the purse, he “had risen to the surface with the other scum amid the bubbling and boiling of the Yankee cauldron.” Honest Abe had since appointed him “to subjugate Texas,” a fact that Semmes had learned from “captured Northern papers.” A force of “not less than 30,000 men was to rendezvous at Galveston,” a port that federal troops had seized from the South.[34] But by the time Semmes arrived at the Texas Gulf Coast, the Confederates had already retaken the city, scrapping Northern plans for an assault on the Lone Star State.

Determined to have something to show for his trip, Semmes carefully shadowed the Union fleet as it withdrew further away from Galveston and deeper into the Gulf. After some shrewd maneuvers, the Alabama lured Union warship USS Hatteras away from the main body of her fleet. The gloaming had given way to dusk, and then at last to darkness. Semmes remembered the night being clear, lit with no Moon. Still, there was “sufficient starlight to enable the two ships to see one another quite distinctly at the distance of a half-mile or more.” Snatching at his chance, he ordered one of the gunners to open fire, and “in just 13 minutes . . . the enemy hoisted a light, and shot off a [flare], as a signal that he had been beaten.” The crew “at once held [their] fire,” but not their tongues. Such a cheer “went up from the brazen throats of our fellows, as must have astonished even a Texan, if he had heard it,” the Captain recalled proudly.[35]

The next anyone in the US Navy heard tell of the slippery privateer were rumors on the wind. The “pirate Alabama” next planned to make for the eastern hemisphere. Semmes hoped to draw the Union’s “fastest cruisers” on a fruitless chase, and thus diminish the strength of “the sentinels” that guarded against Southern blockade-running. According to an “unknown source,” Semmes also intended to re-coal “in the neighborhood of Madagascar.”[36]

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “Paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

- Third, Paywall members have the ability to edit their comments.

- Fourth, Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

- Fifth, Paywall members will have access to the Counter-Currents Telegram group.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.

Notes

[1] In protest, Sir Alexander refused to sign the eventual 1872 Geneva agreement that decreed that Great Britain pay 16 million dollars to the United States, as well as smaller amounts to Italy and Brazil for its role in the CSS Alabama affair.

[2] Diplomats representing Italy, Brazil, and Switzerland also attended the conference.

[3] The Alabama: A Statement of Facts from Official Documents (London: John Snow & W. Tweedie, 1863), 5.

[4] See her 1851 sentimental tear-jerker Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

[5] Ibid., 1; emphasis mine.

[6] Ibid., 3.

[7] Ibid., 3; Emphasis mine.

[8] “Sir Alexander Cockburn’s Judgment,” The Saturday Review, September 28, 1872, 387.

[9] It is unclear whether the Alabama preferred to use the Union Jack or the St. George’s Cross when traveling under British colors; for some time it was controversial to sail under the Jack, strict constructionists maintaining that only royalty or ships bearing an admiral should fly it.

[10] Wilmington, North Carolina Daily Journal, November 2, 1853.

[11] Sally B. Putnam, Richmond During the War: Four Years of Personal Observation by a Richmond Lady (New York: G. W. Carleton & Co., 1867), 39, 78, 80.

[12] A famous example was Napoleon’s conflict with Tsar Alexander I during the Emperor’s abysmal 1812 Campaign.

[13] Speech given by James Henry Hammond, “Cotton Is King,” HST 325 — U.S. Foreign Relations to 1914 (Michigan State University), accessed August 20, 2022.

[14] London Times, January 30, 1863.

[15] Samuel Laycock, “Th’ Shurat Weaver’s Song,” HST 325, accessed August 20, 2022.

[16] “Seizure of the West India Mail by an American Frigate,” London Times, November 28, 1861.

[17] Probably on an order placed by England’s secret-not-secret Confederate agent, James Dunwoody Bulloch.

[18] Messrs. Laird Brothers and the ‘Alabama’ (Liverpool and Birkenhead: Harbord, Johnston, and Hiles, 1869), 3-4.

[19] The Alabama: A Statement of Facts.

[20] “Captain Raphael Semmes of the Pirate Ship Alabama,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Journal, January 10, 1863.

[21] Ibid.

[22] The Boston Daily Advertiser, February 19, 1861.

[23] “Foreign Intelligence,” London Times, September 16, 1862.

[24] “Burning of the Ship Brilliant,” New York Times, October 3, 1862.

[25] Charles G. Loring, England’s Liability for Indemnity (Boston: William V. Spencer, 1864), 5.

[26] Ibid., 6-7.

[27] “Blockade,” New York Times, October 27, 1862.

[28] “Civil War in America,” London Times, October 30, 1862.

[29] See Edward C. Bruce’s The Sea Kings of the South in H. M. Wharton D. D., ed. War Songs and Poems of the Southern Confederacy (Edison, N. J.: Castle Books, 2000), 317.

[30] “On Board the Alabama,” Liverpool Mercury, October 30, 1862.

[31] Ibid.

[32] “The Southern Blockade of New York,” The New York Times, November 11, 1862.

[33] Chicago Times, January 17, 1863.

[34] Raphael Semmes, Memoirs of Service Afloat (Abilene, Tex.: McWhiney Foundation Press, 1996), 56.

[35] Ibid., 56-7.

[36] London Times, January 30, 1863.

Four%20Flags%20Over%20Alabama%3A%20The%20Strange%20and%23038%3B%20Marvelous%20Career%20of%20a%20Confederate%20Raider%2C%20Part%201

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

Introduction to Mihai Eminescu’s Old Icons, New Icons

-

Sperging the Second World War: A Response to Travis LeBlanc

-

James M. McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom, Part 2

-

James M. McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom, Part 1

-

Enlisting in the Military: A Very, Very Bad Idea

-

There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack

-

“Few Out of Many Returned”: Theaters of Naval Disaster in Ancient Athens, Part 2

-

“Few Out of Many Returned”: Theaters of Naval Disaster in Ancient Athens, Part 1

6 comments

Raphael Semmes did not graduate from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1826. The USNA was not founded until 1845. He did graduate from the Charlotte Hill Military Academy, which produced a number of famous alumni before closing in 1976, including (!) Sylvester Stallone.

My source is a January 10, 1863 article from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Journal. Perhaps they were wrong. Wouldn’t be the last time that happened in a New York newspaper.

You made an honest mistake. Thanks for your reply. Respect for your article.

I always appreciate corrections; a good reminder to be vigilant and double-check one’s sources, both primary and secondary.

But that was a useful mistake, because it affords the curious reader, and the tired researcher too, the opportunity to learn about one of the most striking incidents in the history of the USN.

As noted, there was no Naval Academy at Annapolis when Rafe Semmes was a young man. If you wanted to be a naval officer, you learned as a naval apprentice on an actual brig. (The Royal Navy used a similar system.) In 1842 the training ship was the newly christened USS Somers. Several of the midshipman-cadets staged a mutiny, and were hanged. One of them, Philip Spencer, was the son of the Secretary of War. So you can well imagine that this attempted mutiny—and the executions—got plenty of ink, and Congressional attention!

And as you know by now, or have guessed, the United States Naval Academy was founded in 1845 as a direct result of the Somers incident.

Raphael Semmes enters the story shortly afterwards. He had entered the Navy many years before the Somers was launched, but in 1846 he was commander of the Somers when it went down in a terrible squall off Veracruz, during the Mexican War. Semmes’s assignment was fending off blockade runners. An ironical task, of course, given that he ended up as senior officer of a Confederate States Navy whose main occupations were sinking Yankee merchantmen and launching blockade runners!

Another nice irony is that when they were junior officers, Semmes and John Winslow messed together, some 25 years before their ultimate duel-to-the death in the English Channel. Winslow became commander of the USS Kearsarge, the sloop-of-war that sank its near-twin, sloop-of-war CSA Alabama, in 1864.

Neither officer actually died in that encounter, although Captain Semmes’s CSA Alabama certainly did, going down twelve miles off Cherbourg. Semmes eventually transferred his services to gunboats at Richmond, and then followed President Davis to Danville, Virginia, where he took a commission as Brigadier General in the CSA, during the last weeks of the Confederacy.

I have a copy of that commission certificate around here somewhere…

Thanks for the comments, Margot! I had fun writing this one, and I learned a lot.

I go into the Alabama vs. Kearsarge/ Semmes vs. Winslow duel in part 2. Yes, the coincidences surrounding their prior relationship during the Mexican War were fun. When the Northern press discovered that Semmes (who had apparently been injured during the battle) was on the deck of another ship courtesy of obliging Europeans again, the frustration was palpable (and delicious). Did you manage to dredge up the commission certificate?

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.

Paywall Access

Lost your password?Edit your comment