The German Colonial Empire: A Miracle of Progress

Posted By Morris van de Camp On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledBruce Gilley

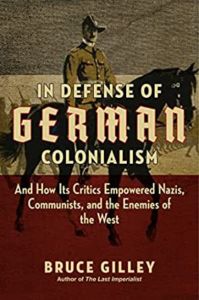

In Defense of German Colonialism: And How Its Critics Empowered Nazis, Communists, and the Enemies of the West

Washington, DC: Regnery Gateway, 2022

Bruce Gilley is a professor who was heavily criticized by a Maoist mob after he wrote an article entitled “The Case for Colonialism [2].” In his latest book, he takes a look at the much maligned German colonial empire, which stretched from Africa to Asia and even into the South Pacific until the the end of the First World War.

Gilley was prompted to write this book after researching the life of a British Empire colonial official, Sir Alan Burns [3]. Sir Alan had been part of the British invasion of German Kamerun, in central Africa. The invasion was ultimately successful but was a tough slog, made very difficult by the tenacious resistance of Germany’s native African soldiers. This resistance raised the question: If German colonies were captured lands whose peoples were being enslaved by tyrannical Prussian despots, then why would African soldiers from these colonies fight so hard against their supposed liberators?

Gilley did some research and found that the idea that the German empire had been a vicious tyranny was wrong. Rather, the German colonies had highly progressive rulers who created prosperous nations in formerly backwards lands. Documented incidents of cruelty, such as flogging, were in fact part of the natives’ customs, and was in fact less severe than punishments meted out elsewhere. The natives often demanded the death or mutilation of a criminal guilty of minor infractions who was instead flogged. Other alleged German crimes such as a labor tax was not onerous, either. All governments require taxes to function, and in cash-strapped areas, roads that led all to prosper could be built with the sweat equity of those who would go on to use them.

The Spirit of Berlin

A case can be made that Europe’s efforts at establishing overseas empires began as early as the Crusades and the Kingdom of Jerusalem, but it is indisputable that European colonialism began in 1492, with Christopher Columbus’ first voyage. The first types of European colonies that were set up fell into three categories: ports and trading centers, often run by the Dutch or Portuguese; military conquests in pursuit of gold, such as Cortés’ conquest of Mexico; and settlements such as Plymouth Colony, where a small group of whites set up a community in keeping with their religious convictions.

The first colonies were developed in a wildcat fashion. Explorers acting with a broad mandate from a monarch were free to do what they wished, and societies as different as Saskatchewan and Guatemala developed as a result. After Brazil became independent in 1822, European governments started to formally organize colonies as part of a national effort with the primary aim being the uplift of the native peoples.

Germany only became a unified nation in 1871, therefore coming late to the European empire-building projects. By then, the Americas consisted mostly of independent nations in their own right. The only places left for Germany to colonize were in tropical Africa and Asia, as they hadn’t been colonized by Europeans due to the threat from disease, but advances in medicine made it possible by the late nineteenth century.

As Europeans started to move into Africa, the possibility for problems to develop between European nations due to overlapping colonial claims was high. In the winter of 1884/5, the Germans therefore hosted a conference where everyone’s colonial ambitions in Africa could be sorted out peacefully. Gilley writes:

This “Spirit of Berlin” was particularly relevant to Germany because its colonial era was just beginning. There was no “dark past” that needed to be excused, reformed, or forgotten. Instead, the Germans took pride that they had set a new standard for excellence in colonial administration. (p. 25)

The Berlin conference has been criticized for not taking into account the natives’ tribal identities, but Gilley shows that this was not true. The conference attendees were very conscious of tribal identities, and adjusted the colonies’ borders to keep tribal territories within one colony or another. Furthermore, there was a not entirely unreasonable assumption that the tribes could unify under a new national consciousness, since they often spoke similar languages and were of the same race.

Africa

The German colonies in Africa were German East Africa, which matched the borders of today’s mainland Tanzania, Burundi, and Rwanda; German South West Africa, which is today’s Namibia; and Togoland, which was in what is now parts of Togo and the Gold Coast.

As with all colonial endeavors, there were several wars. In German East Africa, there was the Maji Maji Rebellion, which was defeated by the German military. Today’s anti-colonialists praise the rebellion, but Gilley shows that it was in fact instigated by native slavers and Muslim fanatics who were seeking to work the area for their own purposes. The Maji Maji were the exploiters, not the Germans. The German suppression of this revolt was so appreciated by the natives that they fought to the end for the Germans during the First World War.

German linguists helped make Swahili [4] the lingua franca of eastern Africa. They formalized the language, published dictionaries, and sponsored instruction in it. German linguists also did this with the Ewe language [5] in Togoland.

Togoland was a model colony until it was captured by the British and French during the war. The Germans initially found the area to be poor, but then quickly developed agricultural industries in cotton and tropical produce. To put it in economic terms, before the Germans arrived Togoland was not even on the production possibilities frontier [7], which was the hypothetical edge of goods and services a nation’s economy could produce. Afterwards, the natives had a chance to make their lives better and Togoland produced genuinely useful goods and services.

German South West Africa is often mentioned negatively in anti-colonialist literature and woke academic circles. This is due to the supposed “genocide” of the Herero and Nama people in 1904. Gilley shows that the Herero and Nama were led by an anti-European fanatic, Samuel Maharero, whose main activities were stealing cattle and causing trouble for the other tribes in the region. The reduction in the population documented by the censuses taken before and after the alleged killings can likely be explained by refugee out-migrations resulting from Maharero’s deeds rather than mass murder. The numbers of others peoples in the area such as the “Basters,” a caste of half-whites from the Cape Colony, also declined, and they were not attacked by any party.

Meanwhile, the Germans reduced travel time from the coast to German South West Africa’s capital from three weeks to three days by building a railroad. Gilley finds it bitterly ironic that anti-colonial and Maoist academics who drink spiced lattes, the ingredients of which originate in several continents, while sitting in Internet cafés then blog about the crisis of “modernity.”

Asia, the Pacific, & the First World War

Germany also had colonies in Asia and the South Pacific. They included New Guinea, the Bismarck Archipelago, and many of the Polynesian islands. The most prosperous colony was Qingdao, on the northern coast of China. Qingdao was a poverty-stricken area which became a German version of Hong Kong after colonization. The population was Chinese; they simply needed German law and order in order to build a functional society and economy.

Then, an anarchist Serb shot Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie in Sarajevo, and Europe collapsed into a more appalling version of the Peloponnesian War. The pre-war treaties had all held that the belligerents’ colonies would not fight each other in the event of a European war. Colonial armies were nevertheless soon locked in battle after the war began. The British Empire quickly captured most of Germany’s African colonies, but in German East Africa the resistance was so fierce that the British were never successful. In the Pacific, New Zealand and Australian troops captured Germany’s Pacific colonies.

Japan conquered Qingdao and several other German colonies in the Pacific Islands. Gilley argues that the British made a terrible miscalculation in allowing the Japanese to take Qingdao. The Japanese were not particularly just rulers, and they used Qingdao as a base from which to make further gains in China. The Japanese attack on China became one of the destabilizing forces that helped lead to the Second World War.

Weimar

It is well known that Germany’s Weimar Republic was dysfunctional. It is also well known that the Treaty of Versailles led to grievances that eventually brought the National Socialists to power, thus further destabilizing Central Europe. The ghosts of the colonies had an impact on the Republic’s fierce domestic politics. Gilley writes:

Overall trade in German colonies had grown by 17 percent a year from 1903 to 1913, but growth fell to just 2 percent year in the same territories from 1914 to 1929. This was in part because German planter families returned to Germany, leaving agricultural sectors in crisis. Along with them went missionary teachers, health workers, engineers, and accountants. German society united to support the return of their colonial settlers — Kolonialdeutschen — after they were expelled or made unwelcome by the mandate powers. Long before France had its Pieds-Noirs or Portugal its Retornados, Germany dealt with the trauma of decolonization on domestic politics. That trauma would have far worse consequences for Germany than for any other major colonial power. Heinrich Schnee coined the phrase “the myth of colonial guilt” (Die koloniale Schuldlüge) to refute the charges made at Versailles and to buck up pride in colonial achievements. German colonies had been beneficial and legitimate, he argued, and the League of Nations system was a failure. The mandate powers should be “honorable” and return the colonies to Germany (with the exception of Qingdao, now restored to China). A “colonial friends” (Kolonialfreund) movement of the 1920s was part of this ghostly apparition in German politics. (p. 186)

There was another issue as well. Gilley argues that the loss of its colonies helped to close Germany’s hitherto open and free society. A former naval captain and prolific journalist, Count Ernst Reventlow, argued against German colonialism in 1907. Reventlow believed that the colonies were distracting Germany from fruitful expansion into other parts of Europe. Reventlow later became a Nazi legislator.

Critical Thinking

Gilley goes on to describe how the Nazis were the first decolonizers, and they influenced later decolonialist thinkers like Frantz Fanon. I found this the book’s weakest argument. It has too much of the “Hitler did it also [8]” logical fallacy. The loss of the colonies was indeed one of the Nazis’ grievances prior to the war, but it was of a much lower priority to them than other issues. Additionally, with so much potential trouble from the Soviet Union, Hitler was certainly right not to want to invest in African colonies.

Another weak part of the book is Gilley’s interpretation of the connection between Hitler and the then Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Amin al-Husseini. The two parties were united in their concern with global Jewry, and were allies of convenience. In the 1930s the Palestinians were starting to feel the pinch from Zionist displacement and were looking for allies anywhere they could find them. For his part, Hitler recognized that his British enemy’s soft underbelly was its non-white empire. The British colonies were often economically impoverished and demanded a constant allocation of military resources. The British, for example, were forced to defend a lengthy frontier in India, leading to considerable trouble in the northwest.

Gilley also doesn’t mention the considerable anti-colonial activity in British and French colonies during the First World War. Had he read Lothrop [9] Stoddard [10], he’d have noticed that the alarming problem of anti-colonialism began developing in places like Egypt as early as 1900, and was in full flower in all the colonies by the time of the First World War.

Gilley is on firmer ground when he describes East Germany’s anti-colonial efforts. German scholars, under the gun barrels of their Marxist commissars, published critical accounts of German colonialism to discredit not only Germany’s colonial empire, but all Western colonies, including the West’s interventions in the Third World during the Cold War. In the former colony of Namibia, East Germany even supported an insurgency against white-ruled and functional South Africa. Gilley documents how Leftist rule in Namibia destroyed many economically productive industries. Land reform, for example, ruined many productive farms, and the new farmers starved on their tiny plots of land.

Gilley is critical of anti-colonialist academics and writers such as Edward Said and Frantz Fanon. He argues that they are motivated more by destroying the West than helping their own people. This is true, but these academics are genuine representatives of non-whites’ envy and resentment of white accomplishments. This is the source of anti-colonial academic thought. It is not rational from a material standpoint, but it is human and natural.

Woke critics of Gilley are correct if they call Gilley a white supremacist. While he extols the virtues of the European empires, he doesn’t praise the Mongolian, Arab, or Japanese ones. But unlike how the term “white supremacist” is usually understood, Gilley is genuinely sympathetic to the decolonized peoples across the Third World.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “Paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

- Third, Paywall members have the ability to edit their comments.

- Fourth, Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected] [11]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

- Fifth, Paywall members will have access to the Counter-Currents Telegram group.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[12]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[12]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.