The Bakony

Posted By Béla Hamvas On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled3,830 words

Béla Hamvas (1897-1968) was a Hungarian writer who was the first exponent of Tradition, as understood by René Guénon and Julius Evola, in his country, and remains a highly respected writer and novelist outside metaphysical circles as well. The following essay appeared in The Hungarian Quarterly no. 3 (March 1937).

When a Hungarian hears the word “Bakony” the picture evoked in his mind is not of the mountain range in western Hungary, which skirts lake Balaton for a hundred and fifty kilometres. Geographical names are usually mere names. The Bakony is different. For a Hungarian it is, primarily, a place of myth and of legend. When St. Stephen christianized the country, those pagans who would not submit to him hid in the vast forests of the Bakony. Ever since then Hungarians associate with this name a desire for independence, a resistance to authority, a spirit which makes for rebellion. They picture a mountain thickly covered with woods, abounding in mysterious precipices, caves, and unapproachable canyons. This is the Hungarian jungle, the hiding place of those who cannot fit into the outside world. Mythical nature herself, wild and elemental, is contained in the word. It is full of mystery, and of paganism, even today, a thousand years after the reign of St. Stephen. We have a feeling that the inhabitants of the Bakony are hardier and less civilised than those who live in other parts of the country. There are trees here which seem to compel humans to revere them as supernatural beings, and to make offerings to them as of yore. Nothing is so easy as to get lost in the Bakony, not because it is pathless or sparsely inhabited, but because there is something confusing and perturbing about it. It seems to be inhabited by forces against which the map and compass are of no avail. The Bakony of myth and legend is a virgin forest, inhuman, heathen and dark, a forest of dense, deceptive vegetation, of lurking dangers, and unexpected ferocities.

My first impression of the place was of a nature to fortify this sense of the mythical. I entered the forest one day in the middle of July 1920, and by evening had reached the summit of Kabhegy, an extinct volcano. It was my plan to spend the night there. It was warm, the sky was clear, not a leaf stirred. I had supper out of my knapsack, collected some hay under a tree, and lying down on it, took out a book and began to read. It was, I still remember, the eleventh chapter of Rousseau’s Confessions. By and by the light waned, I grew sleepy and laid down my book. It was then that I heard a peculiar sound, a kind of hoarse baying, from the valley below. I recognised it at once; it was the baying of a wolf, — a sound that, once heard, can never be forgotten. I waited. Sleep went out of my eyes at once. The howling came closer and was soon accompanied by a rustling in the undergrowth. I had no weapon on me. The nearest village was more than an hour and a half away. Without hesitation I snatched up my things and swarmed up the nearest oak tree. Two minutes later the wolves appeared. There was a number of them, though I could not make out how many. Panting, growling, they hung around until dawn. Their green eyes glowed phosphorescently in the dark, they yawned audibly, whined and smelt at my bed. When the sun rose, they vanished.

There were many who doubted my adventure. It was impossible, they said, that such dangerous beasts should still exist in Hungary. Later my credit was restored by a forester who related that, strange though it may seem, wolves had actually been seen in the Bakony during the war. The State forester had shot one. The others were probably shot by poachers, or killed by the peasants. Since then there have been no more wolves in the Bakony. Other wild animals there are in plenty, of course, especially foxes and wildcats.

Such was my first and deepest impression of the Bakony. In those days the villagers still received one with suspicion. They had never seen a tourist before, and when I appeared with my knapsack they gave me food but no shelter for the night. It was no good explaining that I wished to wander around to see the villages, and enjoy the scenery, the mountains and woods. They did not believe me. What, they asked, was there to be seen in the scenery? One old woman willingly gave me supper, but afterwards, feeling that she had put me under an obligation and so had a right to my absolute sincerity, she looked me straight in the eyes and asked me what I had for sale. She took me for a travelling salesman.

Today the situation is different; most of the villagers know that there are such things as tourists in the world. Board and lodging can be had almost anywhere, even if both are extremely primitive. The fact is that these woods are visited but by few. I have been there in all seasons, yet I have never met a stranger.

[2]

[2]You can buy Julius Evola’s East and West here [3].

The dangerous adventure of my first visit had not damped my spirits, on the contrary, it was an added attraction. I had got a taste of wild Nature which would be far to seek elsewhere. Whenever I have been in those hills I have always met something of the primitive, elemental Bakony. The present generation is doing its utmost to annihilate the ancient world. The forest is perishing fast. The trees are being cut down over extensive areas, and in some places the mountain’s basic substance, the dolomitic lime-stone, is breaking through. The district is extremely poor in water, and the clearing of forest-land has added to its aridity. However, savage Nature, suppressed in one place, breaks out in another. Where the jungle is cleared away bleak desert takes its place. In winter such thick fogs cover the hills that it is positively dangerous to leave the beaten path even for a minute. I have heard of hoar-frosts so heavy that they tore down electric wires 8 mms. thick, and of hurricanes that wrenched iron frames from the concrete. Sometimes snow drifts three feet thick cover the road, and the thunderstorms are terrible in their violence. There is a story of a certain count who was caught by a thunderstorm while hunting, and whose hair turned white in a few hours from the continuous lightning, and the roar of the thunder. Yet there is a kind of fascination in the scenery for all its wildness; even its most awe-inspiring regions have a certain charm. Imposing and yet genial, it somehow makes you feel at home. Not to mention that it is the only place left in Hungary where you can wander around for days without meeting a soul.

Some time ago I started out for a week’s ramble. It has become a habit with me to make tracks for the Bakony whenever I have a few free days. There is everything there that my soul desires, — beauty, peace, grandeur, strength and variety. Each season of the year has something new to offer. But the most beautiful time is undoubtedly the end of May. There are deep and humid valleys where one’s eyes are dazzled by the colourful splendour of the flowers, where the flood of spicy fragrance intoxicates the nostrils, and where one’s ears are filled with the clamorous music of hundreds of forest birds. The grass glistens like silver from the heavy dew, and the sky bums with blue fire. Insects, dragon-flies, bees and butterflies swarm over the blossoming meadows, and at the edge of the wood the brook is still full to the brim as it glides slowly onward under the bushes. It is like this for a few days also in the beginning of September, after the first autumn rains, though with something of the radiance and glamour gone. The summer is hot and parched, so that even the larger streams dry up, the autumn is windy, the spring cold, and the winter almost unbearably cruel.

It was on such a day at the end of May that I got out of the train in Várpalota. The place is supposed to have got its name from a castle built here by St. Stephen. The palace-like edifice that still occupies the centre of the town, and is its only sight, was probably built in the middle of the fifteenth century. It was rebuilt several times and has almost entirely lost its original character. The town itself is insignificant; nevertheless it has a certain historical atmosphere. In Hungary you seldom encounter this atmosphere of antiquity. The oldest buildings extant today were almost all built after the Turkish occupation, while most of them date from the eighteenth century. Of the really old buildings generally only the foundations are left, and even these are sometimes difficult to find; Hungarian architecture is mostly underground. What remains in places like Várpalota, for example, is something of quaintness in the atmosphere. A legend or two, some vague conjectures and guesses; still, that is better than nothing. It is a pleasure to tread on soil where you can still find some traces of your ancestors.

A dolomitic road leads from the town into the heart of the hills. It gives the wanderer the first glimpse of what is perhaps the most characteristic feature of the Bakony: variety. There is fantasy and imagination in the scenery. For half an hour or so you are led through a gorge which might be in Bosnia, or anywhere else in the Balkans. Then all of a sudden you reach a spot where giant trees, beeches and oaks, limes and ashes vie with each other in magnificence, growing darker, loftier and more moss-grown at every step. In a trice the whole character of the place has changed: a while ago you walked through an arid limy waste, now you are in the heart of a Nibelungen forest. Large gray boulders, green-patched with lichen, stand silently by your path, and the moist air is breathless, misty and gray. Minute by minute the valley grows narrower and rockier, and you catch glimpses, through the trees, of its sheer sides rising steeply right and left. Suddenly a bold peak appears, topped by a ruined tower. This is Bátorkő, supposed to have been built in the fourteenth century, and later used as a hunting lodge by King Mathias. Royal even in its downfall it looks with calm, supercilious dignity over the top of the surrounding woods. In another half hour the forest grows sparser, and you find yourself in a delightful grove, where scattered trees with twisted trunks make you think of olive trees, so that your eyes instinctively search for the sea which you feel should complete the landscape. Suddenly you catch a glint of water among the trees, and you come on a tiny pond, with lambs and goats grazing around it. You are in the South, Greece probably. Thus in two hours you have passed through the Balkans, the Thüringian woods and fetched up in Greece. Such is the infinite variety, the marvellous imaginative genius of this place.

After a while I reached the summit of a mountain named “Mark’s Coffer,” in memory of a jester of King Mathias. It is not the only reminder of that King of romantic memory. He had many castles here, for he loved to hunt in the Bakony, and his presence still seems to pervade the place, and to linger in the springs and caves that bear his name.

As I descended the hill towards the village of Tés I could not rid myself of the idea that there is an undefinable but unmistakable resemblance between him and the Bakony. Wherein this resemblance lies it would be hard to say, — probably in what I have called the union of grandeur and charm, magnificence and variety; a quality in which austerity, harshness, and a sort of elemental wildness are happily blended with a tempered fineness, a genial gaiety and grace.

I turned my back on Tés with its eternal draughts and ruined windmills. I am told the wind always blows there, and always from the North. Still going downhill I passed through young woods into the valley below, where lay the meadow I had come to find. I remembered it from my first visit, when the sight of it, as I stepped out of the wood, had made me catch my breath with delight. It had reminded me of Böcklin’s “Field of the Blessed,” not because of any physical resemblance, but because the same spiritual atmosphere seemed to pervade it as hung over the picture. The peace of that flowery spot, its radiant freshness, and gay harmony breathed a sweet joy that seemed not to belong to this world.

Half an hour’s walk brought me to the place which they call Roman Bath. If the meadow had reminded me of no earthly spot, the Roman Bath is almost fantastically like a slice of the Yellowstone Park. Grotesquely shaped rocks, wildly rushing brooks, waterfalls, overhanging boulders, scraggy bushes, prostrate tree trunks and thick, bare roots sticking out everywhere — it was weird and arresting rather than beautiful.

An hour and a half’s tramp led me, through a long and narrow gorge, to the village of Bakonynána.

The thoroughbred Magyar of the Bakony is now almost extinct. History, literature and general belief hold that the Magyar is a typical lowlander, at his best in the plains. This is because the highlander, the Magyar of the forests, disappeared or was absorbed long before history or literature had given him his due. Two generations ago it was still possible to meet the type here and there. A hardy and pagan type it was, wild and untamed, which you could exterminate but never domesticate.

I myself never met what I would call a perfect sample of the woodland Magyar. But sometimes I have come across a peasant, forester or farm hand in whom I seemed to detect some of the features of the Bakony itself — gruffness and softness, gravity and laughter, strength and charm combined. I recall in especial a forester who once took me to see a lime tree which had grown out of the rocky soil of the slope to a height and splendour rarely seen even in the Bakony. I have never forgotten the expression on that man’s face as he looked up at that tree. It was evident that what he felt for it was not love — that would have been too civilised and tepid a feeling — but something like kinship, nay more, the veneration that one feels for a superior being. As he spoke, he showed a flash of snow-white, wolfish teeth, his hands, long and bony, were like the roots of a tree, his movements swift and lithe as a panther’s. A dangerous and admirable type; no wonder our Viennese rulers were afraid of it and brought German settlers to the district to neutralise it. King Mathias, on the other hand, must have been happy among such people. Paul Kinizsi came from this neighbourhood, the man who, according to legend, bringing Mathias a cup of water, used a millstone for a tray. He was as strong as a bear or an Ossianic hero, and his heart was as pure and loyal as a child’s.

[4]

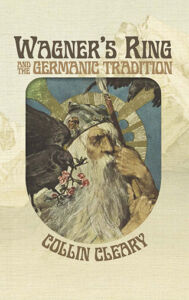

[4]You can buy Collin Cleary’s Wagner’s Ring & the Germanic Tradition here. [5]

I sat on the top of Kőrishegy, the highest peak of the Bakony, and meditated on the sociological significance of the highway-man. More particularly I thought of Joseph Sobri, that hero of legend and song, greatest of all the Bakony betyárs. To this day we do not know who he was or what became of him. A Hungarian writer, lover of the Bakony, wrote a long essay about him in which he maintained that his real name was Joseph Pap. But there are many hypotheses concerning him. In those days there lived in the neighbourhood a family of wealth and standing named Csuzy. In the middle of last century one of the sons — a real Bakony wolf cub — rebelled against parental authority, refused to go to school and finally ran away. No one knew where he went or what became of him, until, fifteen years later, he reappeared precisely at a time when the news of Sobri’s death began to be bruited about. The manner of his reappearance was characteristic. One day a tall, fine-looking shepherd turned up in court, summoned as witness in a trial. His evidence was not to the judge’s liking, and he was reprimanded with some sharpness, whereupon he haughtily declared that he would brook no such tone, and revealed himself past doubting as the long-lost Csuzy boy. The matter caused no little sensation at the time. The shepherd returned to his own people, became once more a gentleman, and having inherited a considerable fortune, settled down and got married. But the neighbourhood was firmly convinced that he and Sobri the betyár were one and the same person.

Let us get this matter clear. What is — or rather was — a betyár? A highwayman, with an organised band of followers, who plundered the rich, lay in wait by the roadside to empty the pockets of merchants returning from the fair, and had confederates and receivers in the villages, on whom he relied for money, food and clothing. His sweetheart was usually a village girl. He very rarely took human life — indeed, he did not willingly kill even a gendarme, preferring to disarm him and leave him trussed up by the wayside, a butt for his jeers and jokes. But Joseph Sobri was not a highwayman to his fellows; they called him a “rebel,” meaning one in whom the Bakony temperament had broken out with elementary force, who had thrown off civilisation and returned to the forest to lead the life of a beast of prey. The Bakony men knew what that meant — had they not each and all a tiny spark of this smouldering wolfishness in them, which it was better not to fan lest it break out in flames. It stands to reason that a rebel has nothing in common with malefactors like robbers, burglars, thieves. He is a mutineer, but only from the point of view of civilisation. Seen from another angle, Joseph Sobri and all the other rebels of the Bakony were merely personifications of the ancient, uncivilised, elementary Bakony spirit. This is why Sobri grew to mythological dimensions, became a hero celebrated in legend and song.

It is of little importance whether he was the son of peasants or of gentlefolk. He was a betyár, a rebel. Not “Strolch” as the Germans would call him, not the “vagabond” of the French nor the “Hooligan” of the English. He was unlike Till Ulenspiegel or Robin Hood. Though he had amusing adventures and liked to fool people, this was not the most important feature of his escapades; the emphasis lay in the fact that he was a creature free as air, bound by no trammels of man’s making. He was witty, quick and shrewd, and there was dash and distinction in all his actions. He was, in fact, a glamorous figure, a hero beloved of the people, who wove legends around him and trembled for his safety when he was pursued. Even the gendarmes regarded him, not as an abandoned and notorious malefactor, but as a dangerous, rare and noble quarry.

The Bakony is best understood through the medium of Sobri and King Mathias. The same love of adventure, the same daring, wit and elegance were in both. But while Sobri might be compared to some distinctive feature of the Bakony — a rocky chasm, a secret cave, a portion of virgin forest, Mathias was the Bakony in its entirety, uniting in himself the wildness of its hills with the smiling serenity of the Field of the Blessed.

I plunged down the south-eastern side of the Kabhegy, towards Nagyvázsony. The slope is so steep here that you can only plunge and slither downward, while going up you must cling to every stump. The hill is cone-shaped, as befits its former volcanic character. Geologists say that its substance is basaltic. And to this day the quality of the vegetation seems to show a lingering memory of spent fires.

I had intended wending my way through the Csinger Valley, but I changed my mind because of the noisy quarry there. Instead I cut across the coppice and through the tangled scrub to the top of the next hill. Here I found the tree which I had climbed on my first visit to escape from the wolves. This time I met a herd of wild boar and one fine stag. Not so long ago, I am told, thousands of pigs fed here; they were a special breed, long-legged and dark-bristled, only found in the Bakony and now extinct. They fed almost exclusively on acorns and never grew fat like the pigs of the plains. The sheep peculiar to this district have also died out; probably they, like the pigs, had a wild strain in them and did not take kindly to civilisation.

As I climbed higher and higher it was borne in upon me that a process of destruction was going on also in the woods. Fifteen years ago there were still lofty beech trees here. What had become of them? Whose home had they heated? The Urkut side was still more or less in its original shape; but the Nagyvázsony side was poor, drab and commercialised. The trees were not of the old magnificent Bakony type. They had been planted for utility, not beauty.

I have a friend who often talks to me of this hillside. He thinks that all along the valley the oaks and birches, beeches and limes, alders and ashes ought to be cut down and peaches, almonds and hazelnuts planted in their stead. Possibly he is right. There is no doubt that the present state of affairs is unworthy of the traditions of the place. One by one the magnificent trunks have been felled, leaving a tangle of crooked side shoots which will be thinned out once, twice, until, thirty years hence, the whole will be cut down once again. How much better to have orchards planted here, 10,000 acres of almonds and hazelnuts and peaches. The soil would be suitable. I have seen such a lavish blossoming of almond trees, one April, in the little village of Aracs, twenty odd kilometres away, as even Tuscany could not have beaten. And I know that the almonds produced there are large and sweet and oily. Yes, this might after all be a worthy transformation of the Bakony. If it must lose its ancient wildness, it should be turned into a vast orchard constantly renewing itself in rare and delicate beauty.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[6]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[6]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.