In Praise of Healthy Vice

Remembering Lothrop Stoddard: June 29, 1883–May 1, 1950

Posted By

Margot Metroland

On

In

North American New Right

| Comments Disabled

1,746 words

This review is published in commemoration of Lothrop Stoddard’s 139th birthday. Stoddard has often been written about and referenced at Counter-Currents; to see these other essays, click on his tag [2].

Lothrop Stoddard

Master of Manhattan: The Life of Richard Croker

New York/Toronto: Longmans, Green and Co., 1931

Our subject today is “The Lighter Side of . . . Lothrop Stoddard.” I’ll be focusing mostly on the delightful Master of Manhattan, his 1931 biography of Tammany Hall boss Richard Welstead Croker. Stoddard has some very interesting, you might say revisionist or contrarian, takes here.

This is a corrective long needed. Stoddard’s big books, mainly The Rising Tide of Color but also The French Revolution in San Domingo, are grave and grim. You might want to read them once, then put them away and wince when you see them on the shelf. Excellently written and researched, but too depressing to pull down again. So it’s always a pleasant surprise to come across his lighter, upbeat stuff.

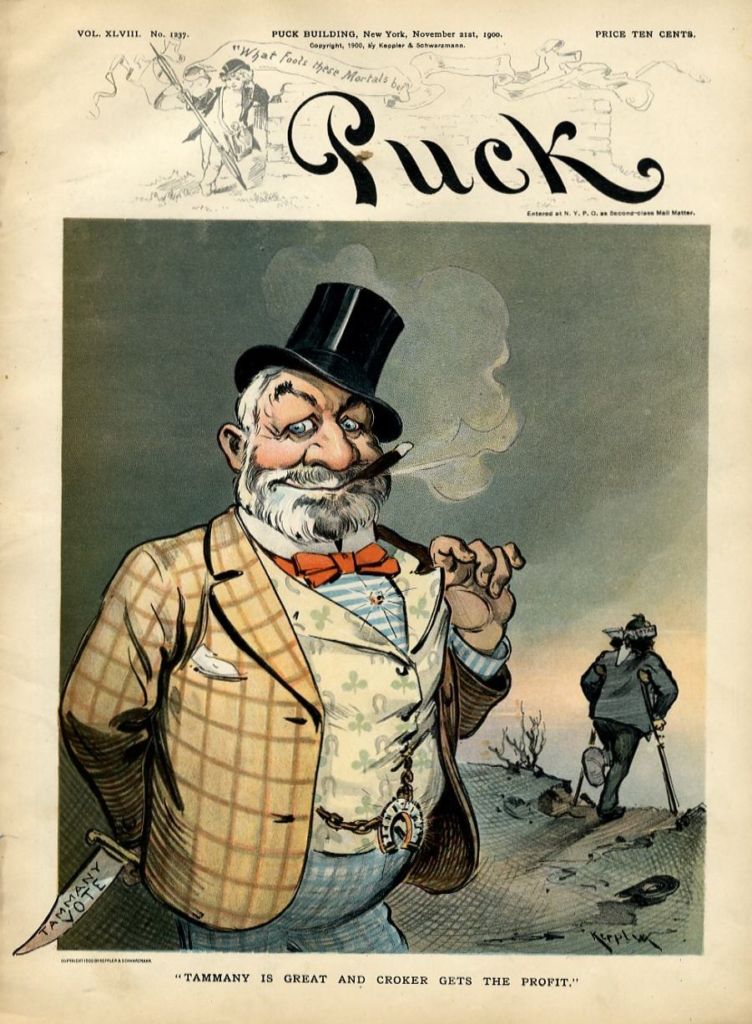

Richard Croker may seem an odd choice of subject, particularly given that Stoddard didn’t usually write biographies. But Stoddard greatly admires Croker, in much the same contrarian way people will express their love of Richard Nixon. “Boss” Croker was perpetually tarred in the press and popular histories as the archetype of the corrupt machine politician, living on graft and fixing elections throughout his long reign at Tammany Hall (peak years: 1880s-90s). With his grey beard and portly frame he somewhat resembled Thomas Nast’s caricatures of his predecessor William M. Tweed, and that might have helped poison the public perception of him.

[3]

[3]You can buy The World in Flames: The Shorter Writings of Francis Parker Yockey here. [4]

Of course Tammany itself is still demonized in popular memory. People can’t quite tell you what was wrong with it, they just know it was somehow bad and powerful and crooked. And that tarry reputation is not accidental. The Tammany Society was a mighty force in New York politics, almost from its founding in the 1780s until its fade-out under Mayor Robert Wagner in the 1950s and ‘60s. A big, familiar target, easy to attack. And so routinely denounced by an endless string of inept “reform” politicians and goo-goos — “good-government” activists.

Croker himself was not particularly corrupt, certainly not by the standards of the Robber Baron era. The Tammany organization sold influence, it is true (what political machine does not?), taking kickbacks and payoffs in return for lucrative city contracts. Croker himself was gifted with shares in streetcar and ice companies, while acquiring extensive real-estate holdings and an auction company. Up against all this we must put the fact that he was also a supremely capable and efficient leader, presiding over a city during the decades of its greatest growth. He literally made the (Elevated) trains run on time, forcing them to arrive at five-minute intervals and fining the Elevated Railroad Company $100 every time a train was late. (The subway system was still some years in the future.) People wanted to drink beer on Sunday even though there was a blue law banning Sunday sale of intoxicants. So Tammany and the police department didn’t enforce that law . . . and the people were happy.

That politics made Croker rich is undeniable. By age 50 he owned a breeding stable of thoroughbred racehorses and a grand townhouse on East 74th Street, in addition to his many other investments. After retiring from Tammany he owned more homes and horses in Ireland and England. He was a serious horse breeder, and two of his stallions, sire and son, won The Derby (in 1907 and 1919).

The 1890s were the great age of the “reformers” in New York politics. There was a priggish Presbyterian minister named Charles Henry Parkhurst, and he swore from his pulpit that he was going to take down Tammany Hall for its corrupt ways. By corrupt he meant Tammany tolerated bawdy houses, gambling dens, and unlicensed “blind tiger” saloons. These persisted — the good Dr. Parkhurst claimed — because Tammany told the police department to take a bribe and look the other way.

No doubt Parkhurst was right . . . up to a point. And his crusade succeeded . . . up to a point. A fusion “reform” ticket ousted Tammany from City Hall in the 1894, but the new regime wasn’t popular. Young Police Commissioner Theodore Roosevelt was told to enforce the vice laws on the books. He shuttered the sporting houses, stopped liquor sales on Sunday, and closed down the infamous backroom card games. The people were not happy, and they voted Tammany back.

When he gets to this part of the story, author Stoddard gives us a good hint why he’s such a fan of Croker. He despises reformist zealots, viewing them as obstructionists and bluenoses. He clearly implies they were the forerunners of the Prohibitionist zealots, whose antics eventually led to the current (1931) epidemic of crime and civic disruption.

He lays into them for several pages:

The psychology of this sort of “reformer” is in many ways intensely irritating, not only to the politicians but to the average run of mankind. There is a cocksureness, a self-righteousness, a lack of human sympathy and understanding about him which tends to arouse mingled anger and contempt. In short: the “reformer” himself has probably been the greatest single handicap to reform . . .

The typical “reformer’s” lamentable ignorance of human nature is strikingly revealed by his desire to coerce the public, by legislative acts or municipal ordinances, to matters which run counter to popular usage and therefore rouse the public to angry defiance. That, in turn, nullifies the special legislation, besides bringing all law into discredit . . .

The “reformer’s” gross lack of human understanding is primarily due to the fact that he is usually obsessed by some fixed idea which he devoutly believes will regenerate mankind and solve society’s problems, if only his idea be fully and resolutely applied. It may be any one of a dozen political nostrums advocated by rival reformist sects; yet in each case the psychology is the same.

This emotional obsession blinds the reformist zealot to the realities of the situation. Whence his deplorable tendency toward intolerance . . .

A “reformer,” in other words, is the sort of person who denounces the chicanery of Richard Croker’s Tammany Hall, but really wants to stop your beer.

Lothrop Stoddard was beguiled by Croker’s efficient practicality, and also by his remarkable life story. Little Richard first arrived in New York from County Cork as a three-year-old with his family. It was 1846; not the most blessed time to emigrate. The Croker family ended up living for a few years in the tumbledown village — “shanty town,” Stoddard calls it — that stood in present-day Central Park, a bit southwest of the Reservoir. (There’s more to say about that shanty town, and I’ll get to it shortly.) Richard Croker’s rise after this, working on a tunnel gang as a lad, and eventually achieving the chairmanship of Tammany Hall — and then ending up as a wealthy horseracing toff in England — is surely the Horatio Alger story to beat all.

Except there’s a lot more to tell, and it’s all interesting. Croker actually was a sort of English toff, by ancestry. His family had been landed gentry in the so-called Ascendancy. They’d settled in Ireland around the time of Cromwell, possibly earlier. Richard’s father, Eyre Coote Croker (a name to be reckoned with), was an army officer and horse veterinarian who fell on hard times. The records are unclear, but I suspect he was heavily in debt. As a bankrupt he would lose his army commission. And so he resigned that and fled to America, hoping to land a nice position, tending to thoroughbred horses. He did find something like that eventually, but it took a while, and the horses were the kind that pulled streetcars.

Meanwhile there were those three years in that shanty town, which has no name in any contemporary map or census. Now, it happens that one of Richard Croker’s later Tammany cronies, George Washington Plunkitt, was born and raised nearby. And he did have a name for it. It was called “Nigger Village” because, well, there were some black people there, along with the Irish and Germans and Swamp Yankees.

In recent years, however, through a desire for political correctness and racial uplift, the area has been rechristened “Seneca Village.” Why Seneca? I don’t know. That designation does not appear in any newspapers or city manuals or Common Council minutes. But the Central Park Conservancy, via engraved signs and glossy flyers, has been promoting “Seneca Village” as a great landmark of African-American upward struggle. So far as I can tell, this hoax originated with a somewhat fanciful 1992 book about the Park. It tells both the Plunkitt story and the notion that the shanty town was an “African-American community.”[1] [6] In reality the shanty town was on the outskirts of a larger village called Harsenville, which disappeared around the 1850s, the same period when our shanties were condemned and swallowed up by the Park.

* * *

How was Master of Manhattan received when published in 1931? I’ve browsed through a handful of reviews and find that they fall into two buckets. Some reviewers describe what they think a book about Croker and Tammany is going to be about. Croker! King of Graft! Tammany bad! That sort of thing. Did they actually read the book, I wonder?

And then there’s the other type of reviewer, who gives us a précis pretty much like the one I wrote above — that is, the book is really a critique of reform mania, disguised as biography. Sometimes Mr. Stoddard himself chimes in with a piquant quote or two. Talking to the New York Evening Post (March 19, 1931) about bluenose reformers and Prohibition, he says, “If they’re going to go the limit in this agitation, and close up the nice little speakeasy where I can get good food and drink, they can count me out. Also if they’re going to take advantage of the situation to inflict a drastic censorship of plays and all that.”

To the New York Times (March 18, 1931) he says, “New York will not be dictated to in its manners and customs. It wants a certain amount of ‘wine, women and song,’ and, willy-nilly, it’s going to get them.”

Ergo: so far from being the stern, mustachioed spoilsport he appears to be in his publicity headshots, Lothrop Stoddard is really more the kind of guy you’d see hanging out with Mayor Jimmy Walker at the Central Park Casino.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[7]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[7]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.

Note

[1] [8] Elizabeth Blackmar & Roy Rosenzweig, The Park and the People: A History of Central Park (Cornell University Press, 1992).