“Fortune of the Field Shall Cast from forth His Chariot”: Elements of Catastrophe & the Bronze Age Collapse

Posted By Kathryn S. On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled10,118 words

By the late spring of 1185 BC, something had gone terribly wrong in the palace-complex of Syrian Ugarit. The city’s leader, Amurabi, had just received a letter from the grand supervisor of Alashiya (Cyprus), asking Amurabi to send what men he could spare to help his beleaguered ally to the east. Cutthroats and bands of foreign invaders were menacing his Cypriot towns. Unfortunately, Amurabi had his own border problems. In a message whose words have lost none of their exasperation or sarcasm after 32 centuries, the ruler of Ugarit replied:

My father, behold, the enemy’s ships came [here]; my cities were burned, and they did evil things in my country. Does not my father know that all my troops and chariots are in the Land of Hatti, and all my ships are in the Land of Lukka? . . . Thus, the country is abandoned to itself. May my father know it: the seven ships of the enemy that came here inflicted much damage upon us.[1] [2]

After dispatching this note, Amurabi immediately sent a plea to the viceroy of Carchemish in his turn, asking the stronger Hittite vassal-state for aid. But all the help he received was a Bronze-Age version of “buck up, buttercup.” You say that “ships of the enemy have been seen at sea!” the viceroy echoed, as if this were news. Are your “troops, your chariots [not] stationed . . . near you? No? Behind the enemy who presses upon you? Surround your towns with ramparts. Have your troops and chariots enter there, and await the enemy with great resolution!”[2] [3] Do as we have done, friend, and “sink your roots into the rock, and face the wind, though it blows all your leaves” afield.[3] [4] Help was not on the way. Within days, an invasion of marauders had wiped Ugarit off the ancient map, the city’s desperate tablet-appeals for deliverance left baking and abandoned in their kilns.

These were extraordinary finds, but Ugarit’s chilling plight was far from unique. During the several decades before and after 1200 BC, every city of note in the eastern Mediterranean, barring a rare few (like those in Egypt proper), was either destroyed by “Sea Peoples” or deserted by their own residents — nearly 50 sites in total. The Collapse plunged the region into a semi-illiterate dark age that lasted for centuries. It was the worst disaster of the ancient world, surpassing even the fall of Western Rome. After the rise of one of the most impressive and simultaneously advanced societies in history, the walls came tumbling down, as if a murderous, blood-starved god had taken his terrible arm and swept the Mediterranean clear of its stone palaces and Bronze-Age magnificence. But if that was not the case, then what did happen?

Almost anything one decides to say about the Bronze Age Collapse (henceforth, “the Collapse”) will be controversial. Who were the “Sea Peoples,” and did they exist at all? If so, were their invasions nearly always quick and violent strikes, or were their movements more gradual and migratory? How does the Trojan War of Homer fit into the narrative, if it was indeed based on an actual conflict? How closely were the various eastern Mediterranean empires — Egyptian, Mycenaean, Minoan, Hittite, Assyrian, etc. — linked to one another through trade and marriage, and can this connectivity be labeled “globalism?” These are just a few of the mysteries historians and archaeologists have asked and tried to answer — and having tried to answer, then engaged in passionate arguments with everyone else belonging to their fields of study. The reason for this lack of consensus is simple: a dearth of sources, while the sources we do have are, to put it mildly, “open to interpretation.” Many of the era’s tablets and inscriptions have left behind them no keys with which to solve the enigmas of their writing systems. Those we can decipher, while valuable, we cannot assume are accurate.

After reflecting on too many Hesiodic forging metaphors, I have arrived at what I consider the closest thing to the truth about those awful and transformative days. The time before the Late Bronze Age (LBA) was, within towns and cities, one of relative inertia and entrenched interests whose rulers sought to achieve what every successful civilization has tried to manage: a definition of its stance towards the “mountain dweller and the nomad” — towards the barbarian, or outsider — whether that meant exploiting them, “fighting them off, reaching some kind of compromise,” or sometimes even incorporating them into the polity.[4] [5] In other words, it was the age-old cyclic relationship between those beyond the walls and those behind them; those who try to impose the law, and those who scorn their attempts. Inflexible LBA cities and their empires ultimately failed to cope with the sometimes volatile elemental forces that governed the Mediterranean region. This, then, is a discussion of what happens when people can longer guard their gates — or, even worse, when they no longer find that guarding their gates is worth the struggle.

I. Cycles of the Sea, Currents of Travel

So when inclement winters vex the plain With piercing frosts, or thick-descending rain, To warmer seas the cranes embodied fly, With noise, and order, through the midway sky . . .[5] [7]

Water

Let us first meditate on that mystical presence — that mother of nations, from which all else drew sustenance. The Inland Sea, or the “Middle Sea” as the pharaohs called it, is itself “immeasurably older” than the oldest of civilizations it has nurtured. The remnant of what geologists call the “Tethys,” an ocean during the Cenozoic-Mesozoic Eras that once stretched across an area larger than the Pacific, the Mediterranean is the last residual gash that remains of waters that date to some of the planet’s earliest days. Yes, it has been the victim of “many violent foldings,” having once been a larger body millions of years ago that has since “heaved itself” up into those wonderful European mountains: the “Baetic Cordillera to the Rif, the Atlas, the Alps and the Apennines, the Balkans, the Taurus and the Caucasus” ranges are the “flesh and bones” of the ancient Tethys that now wear caps of snow rather than coral crowns.[6] [8] And because the Mediterranean’s waters are some of the oldest on Earth, they are comparatively leached of the minerals and small organic materials necessary for flourishing marine life. Certainly, there is enough to sustain a modest reliance on local seafood along its coastlines, but the richest days of Mediterranean activity in the form of fish, crustaceans, mollusks, and other frutti di Mare are long gone.

Still, its waters are beloved, bounded by mountains and flat deltas, as well as the “two great immensities” of the deep blue Atlantic and the piercing white of the Sahara, shading into subtle Sahel “yellows, ochres, and oranges.” Beginning in autumn, depressions from the former, dark and freighted with moisture, roll in, and cities disappear in tumbles and curtains of rain. Summer air whipped up from the dry south blows north, easing trans-Mediterranean travel with trade winds and plaguing it with dust storms that, mixed with spray and sprinkles of rain, occasionally fall as “drops of blood.” It is this more colossal ocean of sand from below that superheats the upper air surrounding the entire basin from May through September, producing those “dazzling [daytime] skies of startling clarity” and nighttime vistas of starlight like nowhere else on Earth.[7] [9] The Milky Way splashes across Scorpius and Sagittarius, glittering in its heavens above the sand dunes of Rhodes.

During the Bronze Age (ca. 3300-1200 BC), this magical and sometimes perilous environment ushered in the first great era of The City — an entity-innovation that would come to define humanity and its civilizations, for good and ill. These burgeoning centers of socioeconomic activity were the foundations of all the mighty Bronze Age empires: Knossos of Minoan Crete, Mycenae and Thebes of Mycenaean Greece, Troy and Miletus of Ionia, Hattusus of the Hittite kingdom, and Memphis of Egypt.

Larger settlements had existed before then, but cities are more than simply large villages. In villages inhabitants work(ed) at the same sorts of activities and are more or less on a level plane with one another. Cities, on the other hand, are structures of hubris, architectures of inequality. They are showcases for monuments, libraries, universities, palaces, and temples; and because someone must manage these cultural institutions, a few city-dwellers will be exempted from manual labor and live lives of the mind (or mindless dissipation). Elite political and intellectual leaders will want their sumptuaries and luxuries to set themselves apart, so they will employ specialists — artisans — to make their fine clothes and jewelry on demand.

Because goods that are distant are more expensive and therefore more desired, they will seize upon ever more expansive trade routes in order to show off their silks from the east, ivories from the south, and potteries from across the sea. Residents will depend on farmers beyond the city walls to grow their food and sell their produce at market; to purchase these, urbanites will need some kind of employment that complements the work of others — a division of labor must follow. City rulers will use these crafts and farming surpluses as the basis for complex webs of exchange. Indeed, when villages become cities, they have given up their “self-sufficient, small worlds” and instead become part of a wider social order, connected to “larger worlds and faraway places.”[8] [10] Those in cities will come to regard themselves as urbane: civilized and sophisticated. Meanwhile, country folk who live outside them will come to seem, in their eyes, “handicapped”: at best, naïve and mentally slow provincials; at worst, hairy barbarians swilling mead from the freshly-hollowed skulls of their enemies.

[11]

[11]You can buy Greg Johnson’s From Plato to Postmodernism here [12]

But how connected were cities in kingdoms like Egypt, Greek Mycenae, Minoan Crete, Cyprus, and Hittite-Anatolia? Ongoing archaeological excavation has unearthed evidence that the Bronze Age Mediterranean was very connected. We have proof that potentates from around the region sent one another letters and diplomatic gifts; they also sent one another their daughters in order to broker treaties through marriages. Divers off the Turkish coast have recently discovered a shipwreck from circa 1300 BC, a vessel bound for Mycenaean Greece and loaded with “raw glass, storage jars full of barley, resin, spices, and perhaps wine, and — most precious of all — nearly a ton of raw tin and ten tons of raw copper,” which were to be mixed together to form that most wondrous of metals: bronze.[9] [13] Scholars have estimated that the ship contained enough of these raw metals to “outfit an army of three hundred men with bronze swords, shields, helmets, and armor, in addition to precious ivory and other exotic items.”[10] [14] A kingly fortune indeed was lost when that ship sank to the bottom of the Mediterranean. Though it may have been an unusually large, rich haul, we can assume that it was really a small part of a lively, crisscrossing network of trans-Mediterranean trade routes.

It would be facile and perhaps “presentist” to call these city connections and shipping activities “globalism,” but the Bronze Age Mediterranean was a miniature, early form of economic and imperialist trafficking that made oceans into highways. To those who lived near the Great Green,[11] [15] the world did not extend much further in any direction. No one there knew about China. If they had heard of India, it was but a vague spot to the east. Sub-Saharan Africa was simply as far south as “Ethiopia,” and the north was a similarly truncated space. To them, the Mediterranean was “the globe.” One might assume that such an economically and politically interconnected region would be resistant to collapse, wary of war, and strong in mutual defense. Others have held similarly optimistic beliefs throughout history, but it seems the opposite has usually been the case.

As cities and empires grew, their trans-Mediterranean linkages grew as well in their complexity and fragility. If cereal farmers in Thessaly suffered bad harvests, the resulting grain scarcity could have a deep, rippling effect. Famines and natural disasters caused commercial traffic to abate — and the risk of piracy to rise. If for some reason the Cypriots could no longer ship the amount of copper to which the Mycenaeans or Hittite leaders were accustomed, then maintaining a viable army became impossible — unless they stole the necessary supplies from someone else. The interests of trade and merchant marine commerce had, by the LBA, become entrenched, calcified, and inflexible.

Having absorbed this, we can understand the precariousness of Bronze Age cities, all of them dependent on the outside world to sustain them, their conspicuous wealth attracting bands of pirates to prey on them (indeed, these pirates and legitimate traders were often the same men). Near the end, the barest of lines separated sailor from buccaneer, coastal town from pirate haven, victim from aggressor. Even minor disruptions could have caused a “systems collapse.” Sacking cities became regular trans-Mediterranean sporting events for violent and/or desperate looters who had long ago learned the art of expert seafaring, of “dining and dashing.” Globalists today are cutthroats and crooks. It should therefore not be too surprising that some of the earliest “proto-globalists” were probably pirates.

Wind

Historians have long blamed the lion’s share of the Collapse on these piratical groups with the catch-all name of “Sea Peoples.” According to this argument, rag-tag but swarming hordes of ship-master thieves, who by comparison would have made Blackbeard seem sweet, descended on and set ablaze any coastal settlement they could find. Indeed, the Mediterranean had long fostered a culture of piracy, its many islands, inlets, and manageable distances making it a corsair’s dream. A profoundly entrenched tradition of seafaring made and unmade civilizations in this way and provided societies with resources and honest employment, while also encouraging unscrupulous groups to discard honesty altogether. The prizes these ventures, licit and illicit, promised were irresistible.

“Islanders,” Thucydides claimed, “were the most active pirates, both Karians and Phoenicians.” The fabled Cretan king Minos was the “earliest known in [the author’s] tradition to [have] acquire[d] a navy, and he controlled most of the sea now called Hellenic, ruled the Cyclades, and in most cases was also their first colonizer, driving out the Karians and installing his sons as governors.” He rid the seas of marauders “as far as possible to direct revenues toward himself instead.” In other words, Minos became the bully with the biggest stick, enabling him to run a monopoly on piracy. During those “early times,” the Greek historian confessed, the Hellenes as well as the barbarians along the coast, and all who were islanders, “turned to piracy as soon as they increased their contacts by sea . . . Falling on unwalled cities consisting of villages, they plundered them and made their main living from this, the practice not yet bringing disgrace but even conferring a certain prestige . . .”[12] [16] Whether or not Minos existed in fact, the words Thucydides used to describe the motives of conquest and plunder were truthful ones. During this disintegrative age, fearful LBA towns constructed walled fortress complexes made from stones so large that later Dark Age Greeks would wonder if bands of Cyclopes tore apart the cliffs with their bare hands to build them.

The direct proof we have linking the Sea Peoples/raiders (they attacked from both land and sea) to the demise of dozens of LBA sites was either very deliberate, or accidental. The authors wrote their mortuary inscriptions on Egyptian pharaohs’ tomb walls, recording their valiant deeds and victories against these would-be invaders, to endure until the world returned to Amun’s dust. Meanwhile, other evidence from the Levant and Greece that archaeologists have obtained through surviving administrative clay tablets were records that their ancient owners intended to keep for a year or so, and were only incidentally baked in the fires that killed or scattered their scribes. Proving the existence of an early but recognizable written form of Greek that preceded the age of Homer by hundreds of years, tablets recovered from Pylos contained words such as wanax (chieftain), gerousia (council), and demos (people), while terms referring to sesame, cumin, and ivory also appeared and provided a freeze-frame for the Mycenaean trading network circa 1200 BC.

But it was the account documenting the depredations of so-called “northerners” that has most interested excavators, a reference signaling the fact that Mycenaean Greece had fallen into internecine warfare among its petty princes, or that Homer’s descendants, the “Argive” Achaeans of northern Greece, had begun to raid southern towns and cities (or both). On the southern Peloponnese and in the eleventh-century city of Pylos, the “northerners . . . after a nightmare of agony during which they gored and destroyed and drowned mercilessly while robbing” the townsfolk, left as quickly as they came, one tablet lamented. Afterwards, “[they] were [left] alone, many still shivering and frightened” from the experience. The enemy showed themselves to be godless as well as ruthless when they “grabbed all the priests . . . and without reason” murdered them. The author confessed to having fallen “back in fear from the [huge] massacre inflicted on [them],” how the attackers then “decided to burn [his] refuge” and to beat his neighbors. “All were dragged from the stable and done evil with hammer-blows.” A section that proceeded to list a “filthy deed” was cut off and left to the imaginations of future readers. “Thus the watchers are [now] guarding the coast” against future evils, the tale ended.[13] [17]

Since we know that the clay of these tablets survived only through burning in the kiln of Pylos’ ultimate Bronze-Age destruction, we also know that the “northerners” overcame all of these “watchers” sent to guard against another landing. Though it be cold comfort (and a very cold case) to the victims, the fires set by the killers themselves ensured everlasting evidence of their crimes.

A few days’ travel to the south, inscriptions on the Egyptian temple at Medinet Habu, the mortuary site of Ramesses III, last pharaoh of the Egyptian New Kingdom, described a much larger encounter. These groups had already destroyed many Minoan and Mycenaean sites, ravaged the Levant, and desolated Anatolia. But Ramesses never quailed, for it seemed the Pharaoh understood how best to defeat them: by stopping them before the pirates could set foot on land in the first place. In the great 1175 BC Battle of the Delta, Egyptian ships met the Sea Peoples off the coast of modern-day Lebanon and began to ram their vessels and launch a barrage of devastating spear and arrow fire. As the Pharaoh’s etchings put it, a collection of wretched foreigners “made a conspiracy in their islands. All at once the lands were removed and scattered in the fray, and no [country] could stand before their arms . . . being cut off [one at a time].”

So successful were these heathens initially, having “laid their hands upon the lands as far as the circuit of the earth,” that in their “foolish and confident hearts” they thought to best the Son of Amun on his own territory. He, Ramesses III, welcomed those “wretched” confederates to the New Kingdom himself. Those “who came forward together on the sea . . . were dragged in, enclosed, and prostrated on the beach, killed and made into heaps from tail to head.” Their ships and their goods, he capsized into the water. The few who “came on [land were overthrown and killed] . . . [and] those who entered the river-mouths were like birds ensnared in the net.”[14] [18] So were the words of Egypt’s last, truly great monarch carved in stone.

It would stand to reason that seafarers from across the region could have been persuaded to join such an adventure, the prospect of despoiling the richest empire in the known world making them foolhardy. At this time the Mediterranean had much in common with the seventeenth-century Caribbean: Both were incestuous, semi-enclosed seas filled with many islands and ethnicities — a highway of empires, traders, and scoundrels. A single ship sometimes carried men belonging to multiple nationalities and castes who, despite disliking one another, could temporarily join forces for the sake of capturing a Spanish galleon loaded with silver, or ransacking a city rumored to have copper stores hidden beneath their forts. We should remember that the number one reason that most compelled the ancients to voluntarily join an army was not “political freedom” or “tyranny”; nor was it rescuing a woman cursed with “the face that launched a thousand ships.” It was the prospect of plunder. To whomever the “Sea Peoples” referred, they were practical men, driven by material desires.

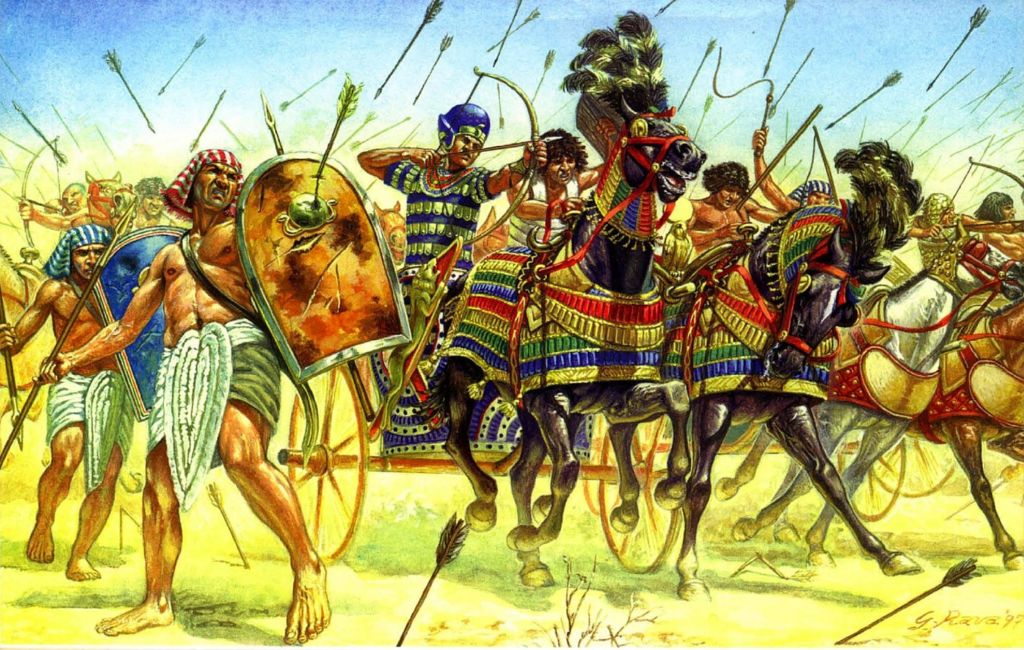

[19]

[19]The boys are back in town: a colorful group of Sea Peoples discuss plans to culturally enrich a nearby city

As for their exact origins, their contemporaries might have known, but we are less sure. The extant records we do have called them different and puzzling names, depending on the source’s location. In the fifth century BC, Herodotus would blame the “Phoecians,” accusing them of having landed on Greek coasts with their ships “freighted with the wares of Egypt and Assyria” — along with plenty of mischief. Luring many women to the beaches with their merchandise, the sailors then “rushed upon them,” seizing and carrying off a number of them with the intent of taking their captives to Egypt.[15] [20]

Meanwhile, the Egyptians called their various groups “Philistines,” “Peleset,” “Tjekker,” “Shekelesh,” “Denyen,” “Lukka,” “Sherden,” and “Weshesh,” claiming that they had all formed a confederacy against the New Kingdom.[16] [21] These Sea Peoples came to war arrayed in sundry and colorful headdresses and kilts. Some wore helmed bands crowned with feathers — Aztec-like in appearance. Others arrived outfitted in the weird horned caps popular in ancient Sardinia, or preening in baggy, swept-back turbans indicative of southern Anatolia (one of the more endearing characteristics of past peoples was a typical unconcern for matching outfits).[17] [22] A hodge-podge multicultural force had come to challenge and pick apart the thinly-stretched and equally multicultural Egyptian empire. A few of these groups — the “Sherden” and “Philistines” in particular — had played important roles for Egyptian monarchs in the past, acting as infantry runners and even as the Pharaoh’s elite personal guard.

Modern speculations on the Sea Peoples’ origins have included the fun but doubtful theory that some might have hailed from as far away as Ireland and ancient Britain. But their bases of operations were most likely in the small and scattered Aegean islands, Crete, Sardinia, Thrace, western and southern Anatolia, and perhaps mainland Italy. The “Philistines” were a familiar name from the Old Testament and frequently figured in military disputes with the “Israelites.” They were originally a resettled people whom the Egyptians and other migratory pressures pushed to modern-day Palestine. There, they achieved supremacy under the Pharaoh’s aegis. Indeed, the Hebrew story of the “Egyptian Captivity” might not have originated in actual slavery and exodus, but in the fact that the fabled Tribes were outsiders from the borderlands and looking towards civilized Canaan with envious hearts. Their “Promised Land” was a “captive” of the Egyptian empire and controlled by Philistinian local muscle.[18] [23] Seen in this light, the battles of Ramesses III and his descendants against the Sea Peoples appear less like simple raids and more like a somewhat concerted series of imperial rebellions brought on by an erosion of pharaonic power, a confluence of regional crises, and Egyptian overreliance on foreigners to man their frontier.

Alongside Ramesses’ bracing account of victory at the Delta, there was another remarkable tale, supposedly narrated by a leader (“Beder”) of a defeated force of Sea Peoples.[19] [24] It began: “Year 8 under the majesty of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Lord of the Two Lands, Son of Re Ramses, Ruler of Heliopolis.” Heed these “words spoken by the scribe of recruits, general of the Lord of the Two Lands . . .” There came a time of hunger, “when trade began to falter” and sea winds were unreliable. There was trouble in the great kingship of Hatti [Hittite Empire]. The chiefs of the lands under the heel of the king of Hatti became rebellious, and “the lands were consumed in petty bickering.” The harbors teemed with warships, and “thievery ran rampant upon the water-ways that [Beder and his] companions were accustomed to traveling.”

During better days they had traded in the islands and coastal regions to the north and west, “where [they] could acquire fine olive oil, metal-work and wool. But trouble had fallen upon [those places], as well.” The ships that had come to them bearing the raw metals that they used for their craft and “the purple dye for their wool[20] [25] now came in lesser numbers, and had little to exchange.” As if to rub the faces of men already prostrate in the dirt, “the gods frowned on them by sending drought, so that their crops failed. The great lords of the palaces began to fight amongst each other, and the kings began to bicker with their own officials.”[21] [26]

This went on for many years, and after each season had passed, the trade route yielded lesser and lesser rewards. One day when he returned from the sea, after having “spent several months upon the trade routes and come home with hardly anything to show,” Beder walked to his house with “all of the weight of an ox yoke upon [his] neck.” His wife and children ran to embrace him, the latter jumping with excitement as they always did, crying, “What have you brought for us, Father?” His wife kissed him and asked, “Beder, my dear, what gift have you brought this time?” Eyes downcast in shame, he answered, “Would that I had something to give you, my pretty bird, but my captain could barely afford to pay me the smallest salary . . . What is more, we lost much of our cargo when we were accosted by Denyen [pirates].” Most of the old harbors were closed and only fortresses greeted them at the shorelines. Meanwhile, “some of the great cities of the western lands that they used to trade with [lay] in ruins in spite of their great forts,” and the people had since fled to the mountains.[22] [27]

[28]

[28]You can buy Julius Evola’s East and West here [29].

At last, he and his companions decided that they could no longer bear this life of want. They swore to be “in no one’s service now but [their] own.” So began Beder’s ten-year career as a buccaneer, plying the seas, “raiding the villages upon the coastlines and accosting the merchant ships that still braved the trading routes.” Among his fantastic tales of adventure were kraken-monster chases through uncharted waters; a supernaturally violent storm that shipwrecked them all upon a remote island where they “were forced to live off the strange plants that grew” there. Two of their companions vanished, “and another went out foraging and came back raving like a mad dog, saying that he had been captured by a tribe of monster women, whose bodies were entirely covered with fur.” The man barely escaped from them with his life and “died soon afterwards of a strange illness.” Themes similar to the Odyssey were apparent in this man’s story, including the “ten years” of wandering. But most striking of all was the fascinating fact that in such epics heroes often embodied the paradoxical dual figure of the wild barbarian without the city walls; but also a tamer of waves, beasts, gods, and men, founder of cities and civilizations (Gilgamesh, Arthur, Alexander, and Davy Crockett come to mind). The narrator went on to relate how Ramesses III, in his mercy, pardoned him and resettled “Beder” in the Egyptian Levant, where the god-king charged him with looking after the affairs of Pharaoh. If any of it was true, then we can feel heartwarmed for Beder, the ex-pirate.

But was this a “happy ending?” A worry niggles its way forward from the back of the mind. In their civilizational hubris and entrenched practice of accepting alien nomads, pirates, and other troublemakers into Egyptian lands and making them into Egyptian subjects, the realm of Shelley’s Ozymandias — the majestic kingdom of mathematical precision — miscalculated. Using a logic that should sound chillingly familiar to First-World Westerners, Beder confessed that before beginning the great raid against his former opponent-turned-patron, he speculated that “perhaps” through invasion “some of us could even come to settle in Egypt, even if by capture, as I have.” After all, “Egypt is never lacking in anything, and even prisoners of battle [there] are often better off than those living freely in the poorer regions” of the world.[23] [30] Was Beder a raider or asylum-seeker, and was/is there ever a difference? Instead of “resettling” these foreign pirates and making them “grateful” subjects; instead of having them join their futures with Egypt’s, Ramesses might have done better to drive them all, boatless and arrow-shot, back into the sea from whence they had come.

II. Cycles of the Land, Chariots of Fire

Discord! . . . She stalks on earth, and shakes the world around; The nations bleed, where’er her steps she turns, The groan still deepens, and the combat burns.[24] [31]

Earth

Perhaps the Sea Peoples, like Beder, left their native lands because of natural catastrophe(s). No one has found definitive evidence that supports the hypotheses blaming the Collapse on climate change, drought, and/or other acts of God. But experts have theorized (long before our current obsession with climate change) that the Late Bronze Age suffered weather-pattern shifts and other natural disasters that plunged the region into socio-ecological chaos. Despite Herodotus’ happy boast that his country of “Greece enjoy[ed] a climate more excellently tempered than any other,” life for the ancients was not always a Mediterranean vacation.[25] [32] Mount Vesuvius erupted cataclysmically at least once during the Bronze Age. The island of Thera/Santorini now looks as if the gods decided to punch a hole through its middle, because its patron volcano blew the island to smithereens sometime around 1500 BC; researchers have recovered pieces of Theran debris from as far away as Turkey and possibly Egypt. Indeed, high seismic activity has always been a Mediterranean feature, for slowly but surely the African tectonic plate edges ever closer to its European counterpart, grinding against it in a shuddering subduction zone of earth and fire. The Cyclades island chain was a product of this mostly invisible gnashing going on beneath the crust — though occasionally, it was very visible.

Recalling an episode from the mid-Bronze Age, the Syracusan ruler Damocles stated that “certain earthquakes took place about Lydia and Ionia as far north as the Troad [northwest Anatolia] and by their action not only were villages swallowed up, but Mount Sipylos was shattered . . . lakes arose from swamps, and a tidal wave submerged the” country.[26] [33] Centuries later in Classical Greece, Thucydides described witnessing on the island of Peparethos a “recession of the waters [that] did not rise again; an earthquake knocked down part of [a] wall, the town hall, and a few other buildings.” Donning his naturalist hat, he (correctly) speculated that “at [the] point where the earthquake [has] the most impact the sea withdraws, and when it suddenly returns with greater force [a tsunami] it causes the flooding.”[27] [34] Destructive tremors of this sort were common episodes, and it is not implausible that a spate of these disasters might have caused cities in Mycenae and/or Anatolia to crumble in on themselves. Nevertheless, most of these LBA ruins showed signs of scorching conflagrations, ash, and evidence of human violence. Modern earthquakes often result in large fires because they can cause gas leaks and break power lines — two things conspicuously missing in the Bronze Age.

Although it is a gorgeous part of the world, its mostly semi-arid climate has been known to plague the Mediterranean region with periodic droughts and poor cereal harvests. Around the time that the town of Emar (located in modern Syria) was destroyed in 1185 BC, someone there sent to the leaders of the capital of Ugarit an urgent plea: “There is famine in [our] house; we will all die of hunger. If you do not quickly arrive here, we ourselves will die of hunger . . . [and] you will not see a living soul from your land.”[28] [35] An equally grim Hittite queen wrote to the Egyptian pharaoh circa 1350 BC, stating, “I have no grain in my lands.” She then sent a trade embassy to Egypt so as to obtain barley and wheat for shipment back to Anatolia. A later inscription belonging to Egyptian Pharaoh Merneptah I mentioned that he had “caused grain to be taken in ships, to keep alive this land of Hatti,” implying that Hittite woes had not improved by the end of that century.[29] [36]

One of Herodotus’ more colorful stories told of times in the distant past when “there was great scarcity through the whole land of Lydia [Greek-held Asia Minor].” For a while the Lydians bore their affliction patiently, “but finding that it did not pass away, they set to work to devise remedies for the evil.” They invented games of “dice,” “huckle-bones,” and “ball,” their plan being “to engage in games one day so entirely as not to feel any craving for food, and the next day to eat and abstain from games.” In this way they passed 18 years of hunger.

Still, the affliction continued and even worsened. In desperation, the Lydian king determined to “divide the nation in half, and to make the two portions draw lots, the one to stay, the other to leave the land.” Those whose lot it should be to go would take his son Tyrrhenus for their leader. So, they cast their lots, and they who drew the latter fate accepted their emigration, “went down to Smyrna, and built themselves ships.” They sailed away in search of new homes and better prospects, until they came to Umbria. There, “they built cities for themselves, and fixed their residence.” Their former name of Lydians “they laid aside, and called themselves after the name of the king’s son, Tyrrhenians.”[30] [37] True or not, the account here recorded by “the Father of History” suggested another possibility for some of the disorder that was so rampant in the LBA: Perhaps famine uprooted whole peoples, their migrations disturbing the balance of nearby countries and causing friction with the populations among whom they traveled and settled.

Whether famines or migrations were causes or consequences of other events remains uncertain. Regardless, such hunger disasters could only have made regional problems more acute and peace more precarious. As the Sea Peoples, driven by anemic trade, emerged from the Mediterranean to descend on coastal cities like wrathful tritons, perhaps wild men from the countryside, driven by famine, came to the same decisions that lured them to the same destinations.

Fire

But perhaps the most convincing cause of the sudden Collapse was neither climate-shifting nor drought, but the revolution in warfare that upended centuries of established tactics and technologies, resulting in a rapid breakdown of law and order. In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries BC, Near Eastern empires’ primary weapons were bronze short-swords, bows, cumbersome spears — and especially chariots. By contrast, eleventh-century BC warriors had largely abandoned chariots in favor of infantries armed with javelins, longer leaf-shaped swords, and self-bows. Horses fell before darts and the teeming ranks of foot soldiers. Bronze dirks broke upon iron longswords. But while it lasted, chariot warfare was a magnificent sight to behold.[31] [38]

The greatest battle of the Bronze Age took place, not outside the fabled city of Troy, but in the scrub deserts near Kadesh — an epic confrontation fought in 1274 BC between the Hittite King Muwatalli II and Egyptian Pharaoh Ramesses II. Ramesses’ host extended for miles as he and his men marched or rode in the merciless Canaanite sun and toward the field of destiny. The two antagonists regarded one another across the plain, one from his camps and the other from the safety of his fortress windows. Knowing that battle would commence the next day, Muwatalli plotted to take his opponent’s force by surprise. He sent into the night two of his “agents,” who allowed themselves to be “caught” by the enemy for the purpose of feeding Pharaoh misinformation — perhaps the first documented instance of espionage and bad intelligence. According to an embarrassingly flattering Egyptian account of the next day’s fighting, the craven “Chief” of the Hittites, “leagured behind strong walls,” refused to come forth from the city “through fear of His Majesty.” Instead, Muwatalli sent men and horses

exceeding many and multitudinous like the sand, and they were three men on a chariot . . . equipped with all weapons of warfare. They had been made to stand concealed behind the town of Kadesh, and now they came racing from the south . . . and broke into [His Majesty’s allied] army . . . Thereupon the infantry and the chariotry of His Majesty were discomfited before them, [while] His Majesty stood firm to the north of the town of Kadesh . . .[32] [39]

Messengers took off their sandals and sprinted to report this trap to Ramesses. Then, “His Majesty appeared in glory [and] assumed the accoutrements of battle . . . gird[ing] himself with his corselet, he was like [the Sun] in his hour, the great horse which bore His Majesty being Victory-in-Thebes.” Ramesses rode into “the rout,” and charged at the “foe . . . being alone by himself and none other with him. When His Majesty went to look behind him, he found 2,500 [opposing] chariotry [at his back and on his flanks] . . . being all the youth of the wretched [enemy], together with its numerous allied countries.” The hot-blooded son of Amun claimed that at that desperate moment, “there was no high officer with [him], no charioteer, no soldier of the army,” his men having scampered “away before them, [and] not one of them stood firm.” Undaunted, His Majesty turned to his shield-bearer and declared: Fear no arrow, nor spear, but “steady thy heart . . . I will enter in among them like the [dive] of a falcon, killing, slaughtering, and casting to the ground. What careth my heart for these effeminate ones of millions at which I take no pleasure?”[33] [40] Lines like this one are the reason why the Bronze Age — the age of Heroes — has always been popular.

Ramesses’ personal chariot guard soon rallied to their god-king, then managed to claw their way out of the swarming attack. “I was before them like Set in his moment,” the young pharaoh boasted, for “I found the mass of chariots in whose midst I was, scattering them before my horses.”[34] [41] Many of the Hittites, initially believing that they had achieved a complete rout, had stopped to plunder the Egyptian camp and so became the victims of Ramesses’ devastating counterattack. Egyptian chariots drove the looters back to Kadesh in a runaway scrape; the heavier Hittite cars were easily overtaken by “His Majesty’s” lighter teams, and thus vanquished. Kadesh was the quintessential Bronze-Age battle, the high watermark of the kind of chariot warfare that sustained and eventually ruined LBA empires. After Kadesh, nothing was the same.

Based on accounts like those that described the tactics of Kadesh, it is clear that chariot warfare was not for the faint-hearted. In the mid-late Bronze Age, clashes between Mediterranean kingdoms primarily involved their charioteers, not their infantrymen. Commanders used the latter as “defensive linemen,” camp guards, city-wall defenders, and chariot “runners”: a supporting staff in a mostly secondary role. Armies often employed mercenary runners from their conquered or frontier territories — places where men were more likely to be swift-footed and ferocious. They rode with their assigned chariots to the front, then ran alongside them as best they could when the battle commenced. Their primary duty was to finish off any of the enemy’s charioteers who had fallen from their perches, or stalled during the previous melée due to horse casualties, broken wheels, injuries, or other misadventures. They wore little armor and carried spears, dirks, and sickle-swords whose curved blades were adept at slicing the hand from the wrist (a common punishment inflicted on male prisoners of war).

The comparison between ancient warfare and modern field games is apt. Occasionally, some innovative tactical mind will revolutionize the game of American football by designing a system of play that manages to exploit everyone else’s weaknesses, in thrall to and shaped completely as they all are by conventional mindsets, by the accepted means of achieving victory. The “Air Raid” offense of the early 2000s was an example of a new method – no huddle, fast-paced, screen-heavy tactics — that often caught other teams off-guard. If carried off well, it neutralized powerful, lumbering defenses. At present, nearly everyone has incorporated the “Air Raid” offense with all its strengths and shortcomings (no, I have not watched football for many years, but I’m Texan, so I know the game well and won’t apologize for it). As in play, so in war: Commanders have always been imitators and adopted their enemies’ successful ideas. As soon as the Indo-Europeans began to use large numbers of chariots in order to win their dazzling victories over foot soldiers in Anatolia, the Eurasian steppes, and northern India, the great age of chariot warfare as the norm spread like wildfire.

The warped, spoked wheel was the chief invention that made chariots effective battle vehicles. Before the Bronze Age wheels were solid, heavy, cumbersome things attached to carts that oxen pulled at a plodding pace. By contrast, these new wheels were made from light hardwoods (cedar or beech), supported internally with evenly-placed spokes and kitted out with platforms of leather and woven mesh. Horses pulled these decidedly sexier chariots at a pulse-pounding speed that left all else in the literal dust. It is not difficult to imagine why those unlucky armies that first had to face a host of chariots manned by young men with lightning-quick reflexes and aggressive warhorses would have quailed; why they were so soundly beaten from the field.

[43]

[43]You can buy Francis Parker Yockey’s The Enemy of Europe here [44].

Like those descriptions about the great chariot battles of Kadesh and Megiddo,[35] [45] the Indian Rig Veda and Mahabharata sang accounts that celebrated this chariot-versus-chariot scene: The hero Virata, “having felled five-hundred warriors in the fight, hundreds of horses and five great champions, made his way variously among the chariots, till he encountered Susarman of Trigarta on his golden chariot.” A duel of the Fates ensued as “The two great-spirited and powerful kings struck out at each other, roaring like two bulls in a cowpen. The . . . fighters circled each other on their chariots, loosing arrows as nimbly as clouds let go their water streams.”[36] [46]

Modern recreations and field tests of ancient chariots have revealed that mesh floors provided a shock-absorbing “gimbal suspension” which allowed archers to enjoy a stable, but mobile base from which to shoot as the chariot traveled over the unpaved earth.[37] [47] At the same time, researchers have proven unlikely the idea that charioteers’ main weapons were spears that they launched at oncoming enemy chariots. It would have been too difficult to hurl them over the heads of their own horses, and only in a video game would even the best spearmen have been able to effectively skewer an enemy charioteer as he hurtled past, or to hit him from behind as they both wheeled away to rally themselves for another charge. Indeed, the Rig Veda confirms this archer-chariot dynamic when it exhorts its “Youths, Heroes free from spot or stain . . . Who shine self-luminous with ornaments . . . with breastplates, armlets, and with wreaths, Arrayed on chariots and with bows.”[38] [48]

At its height, chariot warfare involved hundreds and sometimes thousands of chariot teams charging toward one another on a relatively flat field of battle. The experience must have been wild. Because horses cannot be trained to charge directly into an oncoming host (they will not distinguish it from running headlong into a solid wall), as opposing chariot forces neared their mounts would turn and scatter. After slipping past and around each other, the true test of expert drivers centered on maintaining discipline and coherence. Many battles must have ended quickly, a larger host of chariots causing the smaller or less prepared force to turn and scurry back to some form of safety: behind a city wall or covering infantry fire.

Indeed, chariot warfare was a kind of battle that belonged to kings who lorded over civilized territory. When besieging towns or pursuing barbarians in the hills and highlands, chariots were obviously useless. But for centuries they were enough to keep cities and affluent lands nestled along fertile, coastal plains safe from marauders who tried to threaten them from the marches. Not only landscape, but wealth and resources necessary for its upkeep ensured that charioteering remained a method of warfare that only well-funded rulers and well-organized cities could practice. Great empires could put several thousand chariots in the field while vassal states like Ugarit in upper Canaan might have up to a thousand at any given time. More modest palace complexes had perhaps several hundred. According to decrypted Knossos tablets found on Crete, palaces employed teams of scribes whose sole job it was to maintain a record of chariots — which were battle-ready and required repairs, and which needed one, or both, horses replaced. One scholar has estimated that a single team of chariot horses required nearly nine acres of good grain-land — this in an era and area whose human population also depended on these same, precious acres of wheat and barley!

Charioteers wore costly corselets made of copper scales woven onto leather tunics that hung past the knees, weighing up to 60 pounds. The composite bow, the main offensive weapon carried by chariot warriors, was enormously expensive and took five to ten years to fashion. Layering and lamination of wood, horn, and animal sinew at different stages made it a fearsome but dear piece of equipment. Odysseus’ prized bow was of this type, the one that the returning hero used in a plot to exact vengeance on his would-be-usurpers. So mighty was this composite bow that “Not a man could bend [it] to his will or string it, until it reached Odysseus . . . So the great soldier took his bow and bent it for the bowstring effortlessly. He drilled the axeheads clean,” then quickly “sprang, and decanted arrows on the door sill, glared, and drew again . . . There facing us he crouched and shot his bolts of groaning at us, brought us 190 down like sheep.”[39] [49] Poetic exaggeration perhaps, but the scene captured the legendary glory of this large bow; how strong and steady a man needed to be in order to pull an arrow to his cheek; how powerful and speedy were the darts it let fly; and how indicative of kingly wealth it was.

Suffice to say that charioteering was an elite way of waging war, and its practitioners formed an aristocratic class closely dependent and depended upon by their monarchs. Palaces, for example, often supplied chariot teams with horses, while their riders “owned” their vehicles. In return for service, kings granted charioteers land, their duties and estates passing from father to son.

The Bronze Age dominance of chariot warfare makes Homer’s interpretation of the era’s methods of fighting seem strange, for in the world of Archaic Greece (ca. 800-480 BC), chariots were little more than prestige vehicles and “battle taxis.” Gods and goddesses, kings and heroes descended on the plains before the walls of Troy to enjoin the struggle; but the “true strength” of the Greeks, according to Homer, was their infantry.

By the time of the Iliad’s composition, chariot warfare was far more distant than living memory, and Homer fittingly associated chariots with “old Nestor” — the aged but venerable Greek commander who urged his fellow countrymen to recapture the glory of “earlier times.” He prescribed that “The horse and chariots to the front [be] assign’d, The foot (the strength of war) . . . ranged behind; The middle space suspected troops supply, Inclosed by both, nor left the power to fly.” He then gave “command to ‘curb the fiery steed, Nor cause confusion, nor the ranks exceed: Before the rest let none too rashly ride . . . The charge once made, no warrior turn the rein, But fight, or fall; a firm embodied train.’” And he whom the

fortune of the field shall cast From forth his chariot, mount the next in haste; Nor seek unpractised to direct the car, Content with javelins to provoke the war. Our great forefathers held this prudent course, Thus ruled their ardour, thus preserved their force; By laws like these immortal conquests made.”[40] [51]

We can take Old Nestor at his word — that the “immortal conquests” of his ancestors they achieved mostly by “the foot,” with chariots in an auxiliary role (in the manner that cavalry would later be used in Archaic and Classical wars) and with charioteers wielding spears, despite contradicting evidence and common sense. Or, we can take another view of the matter: that it might have been Homer’s subtle way of admitting that he had no idea what chariot warfare in its heyday looked like.[41] [52] The Archaic Greek tribes to which Homer belonged might even have helped end the era of chariots as the primary mode of Bronze Age conflict. The battle-wheel, a literal cycle of movement and time, had run its course by Homer’s time.

[53]

[53]You can buy Collin Cleary’s Wagner’s Ring & the Germanic Tradition here. [54]

Thus, a hazy situation from a long ago era clears. By the LBA, entrenched interests such as the city aristocracy, monarchy, merchants of bronze, and scribal bureaucracies were all dedicated to maintaining fleets of chariots. They were reluctant to face changing realities. A slew of transformative (and comparatively cheap) innovations in warfare near the end of that era — iron forging from central and northern Europe, the proliferation of longswords, light javelins, improvements in shields and armor — hailed the sunset on the chariot’s golden hour. At some point, the barbarians from beyond realized they could win. Seizing on the discoveries of more northerly European smiths, they began wielding longswords with improved tangs and metal blades. Sickle swords were not efficient killers, but the longsword’s length, balance, and potential swinging momentum could easily lop off heads, sever limbs, or cleave an opponent in half. Lighter javelins effectively incapacitated horses with little effort, rendering chariots lame. By swarming the vehicles, foot soldiers were finally able to overwhelm the elite charioteers.

Barbarians and high civilizations have always had a mutually exploitative and cyclical relationship, and in this case the latter hired the former as cheap laborers and soldiers. Thus did the unlettered and “useful” wild men — both encouraged by their rich city patrons to breed for war and plunder, and with communities of their own people having settled near these centers of chariot-protected commerce — find themselves in a position to cause external and internal strife of the most acute kind. Cities like Ugarit could not course-correct in time; not with all the king’s horses and all the king’s men could they save their proud-towered cities. In the following centuries, infantries would reign supreme; infantries became the centers of gravity in their armies, while chariots ended as they began: as prestige cars more pageant than practical. So began the rise of the polis-nation in which every man, rather than an elite force serving kings on their gilt vehicles, assumed an importance he had not hitherto known, for the common soldier had become the guardian of his native soil.[42] [55] By the time of Homer’s stories, the “strength of war” had indeed shifted to a race of Iron Men.

Conclusion

Despite their inaccuracies, the Iliad and Odyssey revealed still more profound truths. The titular character embodied the complexities of a teetering “global” system, for he was both a member of the “Sea Peoples” and a king; savior and sacker. He represented in the Iliad an agent of change and a barbarian at the gates. But in his own Odyssey, he upheld the conventions of settled life and preserved the civilized realm — personifying the dualism at the heart of the LBA Collapse and combining in one story all the elements in the ancient heroic cycle. The words of Odysseus himself can fuse the themes of this essay together. They suggest that the “Sea Peoples” harrying the Aegean coasts were likely other Greeks from the wilder north (where Homer’s people originated), or similar groups from seafaring islands seeking booty in the comparatively rich southern towns, often glutted with trade goods, fine olives, women, and wine. Having at last arrived on the island of Ithaca, disguised as an old beggar, Odysseus regaled a faithful forester with an account of his travels — a tale of improvised falsehoods and half-truths. He was a great warrior once, he claimed, the son of a wealthy Cretan man whose relations had disinherited him. Thus, he made his way in the world himself, never fearing death but always going “in foremost in the charge, putting a spear through any man whose legs were not as fast as [his own].” Such was his “element, war and battle. Farming [he] never cared for, nor life at home, nor fathering fair children.” All his joy lay “in long ships with oars . . . polished lances, arrows in the skirmish, the shapes of doom that others shake to see.”[43] [56]

Then came the part of Odysseus’ long-winded yarn that closely resembled the Sea Peoples’ exploits, like that described in “Beder’s tale” — that resettled ruffian and one-time Egyptian invader. “Evil days . . . were stored up in the hidden mind of Zeus . . . [and a] lust for action drove” Odysseus’ alter ego “to go to sea in command of ships . . . bound for Egypt.” Nine of them he “fitted out; [his] men signed on and came to feast with [him], as good shipmates, for six full days.” After sacrificing to the gods, they embarked on the seventh, hauling sail “away from Krete on a fresh north wind effortlessly, as boats will glide down stream . . . for five days.” And on the fifth they “made the [Nile] delta.” He brought his squadron to the river bank with one turn “of the sweeps.” Though he warned his men “to wait and guard the ships” while he sent out patrols, “reckless greed carried them all away to plunder the rich bottomlands.” The raiders from the sea “bore off wives and children, killed what men they found.”

When this news reached the capital city, “all who heard it came at dawn . . . horsemen, filling the river plain with dazzle of bronze.” The Egyptians’ “scything weapons left [the] dead in piles, but some they took alive, into forced labor.” The captain who claimed before never to have feared death nor enemy spear “wrenched [his] dogskin helmet off [his] head, dropped” his weapon, then “ran for the king’s chariot and swung on to embrace and kiss his knees.” For fear of “the great wrath of Zeus that comes when men who seek asylum are given death,” the Egyptian King took pity on the defeated seaman, spared his life, “placed [him] on the footboards, and drove home with [him] crouching there in tears.”[44] [57]

The story reads as if it were an LBA account taken from the walls of an Egyptian crypt, the lamentations of a sea captain cast down before the might of gods and kings. Odysseus braved the waters and survived the sea winds, crossed mountains and avoided the foundering rocks so that he might finally light the hearth fires of his home. All this implies that by the time of Homer’s composition, the memories of the LBA Sea Peoples had become grist for familiar folk legends. Heroes like Odysseus, Ajax, Agamemnon, and Achilles — men who may have hastened the fall of the Bronze Age, rather than being characteristic of its splendor — were amalgamations/condensations that kept burning in Greek cultural forges both the traditions of iron and bronze; piracy and probity; and violent, even barbaric adventures in foreign lands, as well as eulogies commending the virtues of settled, civilized life in one’s native country — dualisms close to the Indo-European heart. Homeric tales turned what could have been memories of an era of unredemptive loss, violence, and barbarism into one with a message of transformative heroism. Without agony there is no worthy aristocracy: two words that come to us from the ancient Greeks. Odysseus was a better man when he arrived in Ithaca dressed as a humble beggar than when he first landed on the beaches of Troy as a feted Achaean king riding to battle in his crested helm and gilded chariots of war.

But lest we end on a note that is too sanguine — especially on the topic of one of the worst human disasters of all time — let us remember how terrible, if necessary, cycles are: We need only think of the elemental and physical processes of birth, death, and decay to realize that making and unmaking are rarely pretty things. There is that worry again worming its way forward from the back of the mind. A North Carolina community of farm-worker signatories recently wrote to the “entrenched interests” above, to our elite “thought-leaders” who have so far refused to correct their current and calamitous courses. Substitute “my father” for “our government,” and the coming kiln fires appear hot and certain indeed.

At present, these concerned citizens charged, “our government under President Biden . . . continuously fails” to correct its “biggest” problem: “immigration border entry.” We are dealing with “the highest ever historical migrant surges upon our nation’s borders,” and recent policy changes made by “our government . . . will probably bring heavier influxes” still. Yet, “our president doesn’t have firsthand knowledge of our border crisis, because he has failed to even go [there]! Our government has already reported losing one-third of the immigrant children” it has taken in, “so clearly” it is unable “to keep track of [any] previous immigrant” waves. Now, “we are to believe [that it is] capable [of] keep[ing] track of more volumes” coming every day?[45] [58]

“My father, behold, the [caravans] came [here]; my cities were [ruined], and they did evil things in my country. Does not my father know that all my troops and chariots are” otherwise occupied and castrated of any effectiveness besides? “Thus, the country is abandoned to itself. May my father know it: the [invaders who] came here inflicted much damage upon us.” Expect not even a preposterously bracing letter telling us to stand firm in “great resolution!” to appear in our hour of need. Help from that quarter, dear readers, is not on the way.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[60]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[60]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.

Notes

[1] [61] Jean Nougaryol et al, “Sea Peoples, Documentary Records, Letters at Ugarit” (1968) Ugaritica V: 87–90 no. 24.

[2] [62] Ibid.

[3] [63] Quote from J. R. R. Tolkien, Unfinished Tales of Númenor and Middle-Earth (New York: Harper-Collins, 2007), 296.

[4] [64] See Fernand Braudel’s The Mediterranean in the Ancient World (New York: Penguin, 1998), 36.

[5] [65] Homer, Iliad (Project Gutenberg, 2006), III, 86-7.

[6] [66] Braudel, 33.

[7] [67] Ibid., 37-8.

[8] [68] See Greg Woolf’s The Life and Death of Ancient Cities: A Natural History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020), 5-6.

[9] [69] By itself, copper is a soft metal that cannot maintain a sharp edge, but when smiths mix copper and tin, the resulting alloy — bronze — makes sharp and sturdy blades.

[10] [70] Eric H. Cline, 1177, BC: The Year Civilization Collapsed (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014), 74-5.

[11] [71] A reference to the Mediterranean that is likely a mistranslation of pharaonic texts; nevertheless, it is an evocative name.

[12] [72] Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1998), 5.

[13] [73] R. M. Shurmer, “The Pylos Tablets” in “Document #6: Accounts of the Sea Peoples” (September 2010).

[14] [74] William Edgerton & John Wilson, Historical Records of Ramses III, 30.

[15] [75] Herodotus, The Histories (Roman Roads Media, 2013), 3.

[16] [76] Edgarton & Wilson, 30.

[17] [77] We later have armies, mass-produced clothing companies, and probably the Victorians and their passion for “correctness” to thank for the admonishment that we must “match.”

[18] [78] On page 120, Robert Drews in his The End of the Bronze Age (1993) agrees.

[19] [79] There is a 99% chance that this story of “Beder’s” is a work of fiction. Nevertheless, the account does agree with the invaders’ motives, fate, and “resettlement programs” that we know took place.

[20] [80] “Purple dye” was probably a reference to the Phoenicians, who traded in that sort of thing.

[21] [81] Shurmer, “Inscriptions from Medinet Habu” in “Document #6: Accounts of the Sea Peoples.”

[22] [82] Ibid.

[23] [83] Ibid.

[24] [84] Homer’s Iliad, IV, 130.

[25] [85] Herodotus, 223.

[26] [86] Carlos J. Moreu, “The Crisis of the Sea Peoples, Part 4: Alaksandu of Wilusa and the Prince Alexandros of Troy, a Plausible Historical Connection” (2022).

[27] [87] Thucydides, 173.

[28] [88] Ugarit Text RS 34.152, Bordreuil 1991, 84–86.

[29] [89] Cline, 143.

[30] [90] Herodotus, 44.

[31] [91] For an excellent examination of the revolution in LBA warfare, see Robert Drews’ The End of the Bronze Age: Changes in Warfare and the Catastrophe Ca. 1200 BC (Indianapolis: Princeton University Press, 1993).

[32] [92] Alan Gardiner, The Kadesh Inscriptions of Ramesses II (Oxford, UK, 1960), 65-75.

[33] [93] Ibid., 74-6.

[34] [94] Ibid., 76.

[35] [95] Megiddo was another epic chariot battle fought between Egyptian Pharaoh Thutmose III and rebellious Canaanite subjects in 1457 BC, resulting in an Egyptian victory.

[36] [96] Mahabharata IV, 47 37, 10.

[37] [97] See Olle Bergman’s “How War Chariots Performed” in Ancient Warfare, XV, no. 3, 14-15.

[38] [98] The Rig Veda, Book I, Hymn LIII (HolyBooks.com [99]).

[39] [100] Homer’s The Odyssey, XXIV, 584-5.

[40] [101] Homer’s The Iliad, IV, 124.

[41] [102] See Drews’ The End of the Bronze Age, 189-92.

[42] [103] See Drew’s The End of the Bronze Age, 369.

[43] [104] Homer’s Odyssey, XIV, 452.

[44] [105] Ibid., 453.

[45] [106] “Letter: Our Border Crisis Affects Us Locally [107],” Mountain Press (May 20, 2022).