The (Real) Hollywood Secret Agents

Posted By Morris van de Camp On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled 3,592 words

3,592 words

Argo (2012) is an outstanding movie. It won three Oscars and was nominated for many more. It tells the story of the Iranian Hostage Crisis, where Iranian “students” overran the US embassy and captured all but six of the diplomats and embassy staffers. The reason for Alan Arkin’s [1] nomination for Best Supporting Actor can be shown by a simple facial gesture he makes when he is angered by the Iranians and is sympathetic toward the hostages. Arkin’s acting is nuanced and clear. It excellently propels the story forward.

The movie’s excellence arises out of its mastery of storytelling basics and excellent pacing. Most importantly, the Iranian antagonists are competent, heightening the suspense. The film’s climax includes an old fashioned, 1970s-style police chase scene that ends up working. Argo also emphasizes the solid values of loyalty, hard work, professional excellence, perseverance in the face of adversity, and revival after decline.

Argo tells the story of how CIA agent Tony Martinez [2] (Ben Affleck) is brought in to exfiltrate six personnel from the United States embassy in Iran who had escaped when it was seized by the Iranians in 1979 and the staff taken hostage by revolutionaries. The fugitives then took shelter at a somewhat safe location in the Canadian ambassador’s official residence in Tehran, but have no way of leaving the country without being detained. Martinez is brought on board by his boss, CIA agent Jack O’Donnell (Bryan Cranston). Martinez develops a plan to recover the diplomats using a cover story in which he and his team will claim that they are Canadian moviemakers on a location scout for a science fiction adventure film called Argo.

Martinez’s plan is to use fake Canadian passports which will be sent to the Canadian embassy in Iran via a diplomatic pouch [3] and a fake movie script, and then rendezvous with the escaped diplomats at the embassy. Once there, he will get them home by flying them out on a commercial Swiss aircraft at Tehran’s airport. They will pass through customs and immigration as “Canadian filmmakers.”

Martinez convinces two Hollywood insiders, Lester Siegel (Alan Arkin) and John Chambers (John Goodman), to advise him on how to set up a real production company to create the fake movie. But to understand the film’s context, the Iranian Revolution must be discussed.

The Road to Revolution

Iran’s breakout from Anglo-American “control” was inevitable. The Iranians are Indo-Europeans and their DNA markers have a high degree of association with the “Yamnaya [4] culture [5].” Yamnaya is the new word for the Aryan warriors who were the original Indo-European language speakers [6]. Iran is thus a dynamic society.

Iran’s social foundation is built upon a Persian ethnic core, and the Persians created a great empire and influential culture. The Persian Emperor Cyrus the Great is mentioned positively in the Bible. Isaiah 45 1 -3 (KJV) [7] reads:

Thus saith the Lord to his anointed, to Cyrus, whose right hand I have holden, to subdue nations before him; and I will loose the loins of kings, to open before him the two leaved gates; and the gates shall not be shut; I will go before thee, and make the crooked places straight: I will break in pieces the gates of brass, and cut in sunder the bars of iron: And I will give thee the treasures of darkness, and hidden riches of secret places, that thou mayest know that I, the Lord, which call thee by thy name, am the God of Israel.

The ancient Greek historian Herodotus described the Persians’ excellent postal service:

There is nothing in the world which travels faster than the Persian couriers. The whole idea is a Persian invention, and works like this: riders are stationed along the road, equal in number to the number of days the journey takes — a man and a horse for each day. Nothing stops these couriers from covering their allotted stage in the quickest possible time — neither snow, rain, heat, nor darkness. The first, at the end of his stage, passes the dispatch to the second, the second to the third, and so on along the line, as in the Greek torch-race which is held in honor of Hephaestus.

Persians also developed the paper check to safely transmit money. The word itself, check, originates from the Persian word for document or contract. It is also very likely that Persian blacksmiths influenced the development of the Vikings’ steel swords. The Vikings got to Persia by traveling through Russia’s rivers to the Caspian Sea [8].

[9]

[9]The genetic researcher Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza pointed out that Iranians are closely related to other European groups. White, Indo-European groups are extremely competitive and are often a danger to each other.

In 1953, the British and Americans launched a coup against the then Prime Minister of Iran, Mohammad Mosaddegh. The coup ended with Mohammad Reza Pahlavi being crowned the king, or Shah, of Iran. The Shah was a major ally of the US and Great Britain, but his reign was always tainted by its undemocratic start and reliance on foreign support.

[10]

[10]You can buy Trevor Lynch’s Part Four of the Trilogy here. [11]

The coup was not entirely a negative event. The Americans were taking considerable casualties in the ongoing Korean War at the time, and Cold War tensions were high. It was not unreasonable to believe that the Soviets might have tried to bring Iran into the Communist bloc, and many Iranians supported the coup and the Shah. Regardless, it set events in motion that ultimately led to revolution.

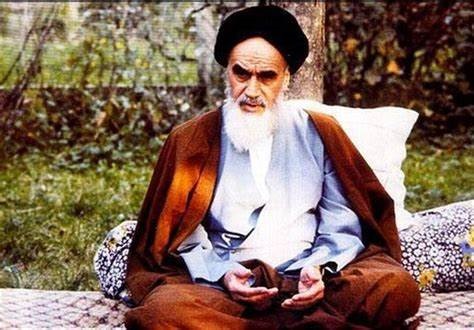

The 1979 Iranian Revolution was launched as a result of the decades-long metapolitcal efforts of Ruhollah Musavi Khomeini (1900-1989). Khomeini attended the Shi’a seminary in Arak, Iran in the early 1920s. There he also studied poetry and philosophy. He eventually became a teacher in Qom, Iran and Najaf, Iraq. His first political efforts took place in 1942, mostly centered on outrage over the Iranian monarchy banning the hijab, although there were other issues such as using the Persian calendar rather than the Islamic one and toleration of the Baha’i faith. He was also part of the movement of Iranian clerics who sought to lessen British influence in the country.

Khomeini continued to teach and study throughout the 1940s and 1950s. We know that he made friendly outreaches to the Kennedy administration, but he never received any response. He was arrested in 1962 for his increasingly outspoken opposition to the Shah’s policies. The arrest made Khomeini a hero to many Iranians. There were riots in Tehran in response. Meanwhile, Iran’s population was undergoing an increase in access to education and urbanization. This young, literate, and newly-urbanized population was seeking Eigentumsprämie — a place in society where they could feel proud. It was this young and educated population that supported Khomeini.

[12]

[12]The Ayatollah Khomeini was a deadly serious man. He was 80 before the ideas he’d developed could finally be applied in the real world. He thought about moral issues his entire life, and this served him well after he came to power. He outfoxed the Carter administration and later defeated an Iraqi invasion, although his nation ended up being isolated from most of the world.

In November 1964, Khomeini was exiled. He eventually went to the Shi’a intellectual center in Najaf, Iraq and recorded his sermons on audio cassettes, which were smuggled back to Iran. The Iraqi government later decided to deport Khomeini and he moved to a Paris suburb, where he continued his metapolitcal activities under the protection of the French police.

While he was in exile, Khomeini developed the concept of Valayet-e faqih [13] (ولایت فقیه): rule by clerics. It was this which gave ordinary Iranians the idea that their government could be one of religious leaders instead of a monarchy, but more importantly it suggested to Iranians that it could be aligned with the interests of the vast majority of their people rather than a globalized elite. Khomeini’s fight with the Shah was analogous to the Prophet Elijah’s conflict with King Ahab in the Bible.

Khomeini’s near enemy was the Shah, while his far enemy was President Jimmy Carter. Like Khomeini, and many other men who rise politically or socially, Carter thought hard about moral issues for much of his life. He was a “born again” Christian, a Sunday school teacher, and influenced by the Protestant theologian Reinhold Niebuhr.

Carter launched his political career by winning an election for the Georgia State Senate. He initially lost the election, but proved that fraud had been in play and got the job after a recount. His meteoric political rise followed. He eventually became Georgia’s Governor by carefully navigating “civil rights” politics. He was for “civil rights,” but hid that fact during campaigns. When he finally came out against “discrimination” at his inaugural address, there was an audible groan from the audience. Many there didn’t support “civil rights” and they realized they’d been had. This double-dealing both helped and hurt Carter politically.

Carter became President in part due to fortuitous events outside his control. The public was still angry about the Vietnam War and the Watergate scandal and President Ford was unpopular, so Carter’s façade of honesty during the election was an asset.

Once Carter was in office, unfortunate events outside his control damaged his presidency. He was faced with an inflation crisis whose complex origins reached back as far as the late 1960s, and the energy crisis of the 1970s was caused by OPEC’s monopoly on oil production. Carter’s Democratic Party was likewise crumbling. The party’s base were Irish Catholics in the northern US and Southern Protestant whites, but “civil rights” caused these groups to switch to the Republicans. Meanwhile, Carter failed to charm important people, such as members of Congress, and did not defend his own Chief of Staff during a media feeding frenzy against him. Thus, by 1979 Carter was already in deep political trouble.

The US Embassy in Tehran

Officially, the Shah left Iran to go on vacation in January 1979, but in fact he was going into voluntary exile because popular support for his rule had declined to such a degree that he couldn’t continue to hold power, despite resorting to violence and military rule. Khomeini’s supporters weren’t the only contenders for power, however, as Marxist revolutionary groups were also active amidst the chaos. Americans started leaving Iran as the situation deteriorated, and the State Department drew the embassy down to a skeleton crew.

On February 14, 1979, a group of Marxist guerrillas stormed the US embassy, held the staffers for four hours, and then let them go because Ayatollah Khomeini refused to endorse Marxism. Members of the Council of Revolution and others representing the new government resolved the conflict quickly and peacefully. Meanwhile, Khomeini’s supporters organized to beat the Marxists in street brawls and began to develop a stronger provisional government. Khomeini employed an Assembly of Experts to draft a new constitution.

American embassies are typically secured by a detachment of US Marines, but their authority only extends to the edges of the embassy’s compound. The bulk of embassy security is provided by the government of the nation in which they are operating. The Tehran embassy’s plan for its staff in the event of a second attack was for everyone to flee to the second floor of the chancery and shelter in place until the Iranian government authorities restored order.

Throughout 1979, the embassy was surrounded by shouting protestors. The new Iranian government wanted assets of the Shah’s regime which had been frozen by the US to be released to them. The Shah himself was traveling from place to place. His travels eventually became a moral concern, and his plight reflects the problem that America often has with its allies. In a perfect world, the United States would have no entangling alliances and there would be amicable relations will all other nations. Unfortunately, however, people abroad can also decide that you are an enemy. With that in mind, you might need to support your allies when they are having problems so that they will support you when you’re in trouble.

The Shah was dying of cancer, having been battling it for four years. His friends in the United States mobilized on his behalf. Carter initially didn’t want to do anything for him, fearing that Iranian radicals would target the embassy in response. However, David Rockefeller, President of Chase Bank, and former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger believed that he Carter administration should admit him for treatment in the US. Carter reluctantly agreed.

The Iranian revolutionaries saw things differently: They thought the US was going to try to restore the Shah. On National Students Day — November 4, 1979 — the usual protest around the US embassy was even louder and larger than usual. The embassy staff did not think there was anything wildly amiss, however, but within the crowd was a group of Khomeini supporters who had planned to take them as hostages. Prior to the attack they’d reconnoitered the grounds and found the weak point in the chancery’s defenses: a basement window.

[14]

[14]You can buy Return of the Son of Trevor Lynch’s CENSORED Guide to the Movies here [15]

Diplomat Al Golacinski saw the crowds breach the wall and warned the other diplomats over the radio. The embassy staff, including Iranian employees, headed to the chancery’s second floor to shelter in place. Then, Golacinski went out to “reason” with the mob. He was captured, led through the basement to the second floor’s entrance, and was then threatened with burning and shooting. More staffers were captured. Within the embassy’s secure area staffers began destroying sensitive documents, using a commercial shredder to chop some of the papers up, but they were only cut into strips. The Iranians hired carpet-weavers to put the strips back together. This was shown in the movie and heightened the suspense. Would the Iranian counter-intelligence agents discover the identities of the Americans before they could be rescued and capture them?

The scenes in Argo where the students storm the embassy are excellent, including the worried facial expressions of the Iranians seeking exit visas as well as the clear expression of fear on the face of the actress playing an American embassy staffer when she is grabbed and blindfolded.

The embassy staff had assumed they could remain on the second floor of the chancery for two hours, which would give the authorities enough time to put a stop to the violence. They did this, but the Iranian government did nothing to stop the students, and after two hours they were forced to surrender.

It is clear that Khomeini didn’t authorize the attack in advance, but once it happened, he decided to back it. The victory over the Americans gave him the opportunity to purge his revolutionary provisional government of any rivals as well as the moderates.

The Hostages

After the embassy was overrun, its staff were divided into three parts. The great majority of the Americans who were captured were kept in the embassy itself. There they were tortured, such as by being walked into trees while blindfolded. Some were subjected to mock executions. The chargé d’affaires, Bruce Laingen [16], and two others were captured and held at the Iranian Foreign Ministry. But as mentioned before, six of the diplomats evaded capture and went to the British embassy, but it was also surrounded by “students,” so they finally made it to the Canadian embassy and found refuge.

Bruce Laingen’s wife Penelope Babcock Laingen [17] created a national movement to demonstrate solidarity with the captives when she tied a yellow ribbon around an oak tree in her front yard. Soon, there were yellow ribbons across the United States in solidarity with the hostages. A yellow ribbon honoring a loved one away on a military campaign or who has been captured is an American tradition dating back to the Civil War.

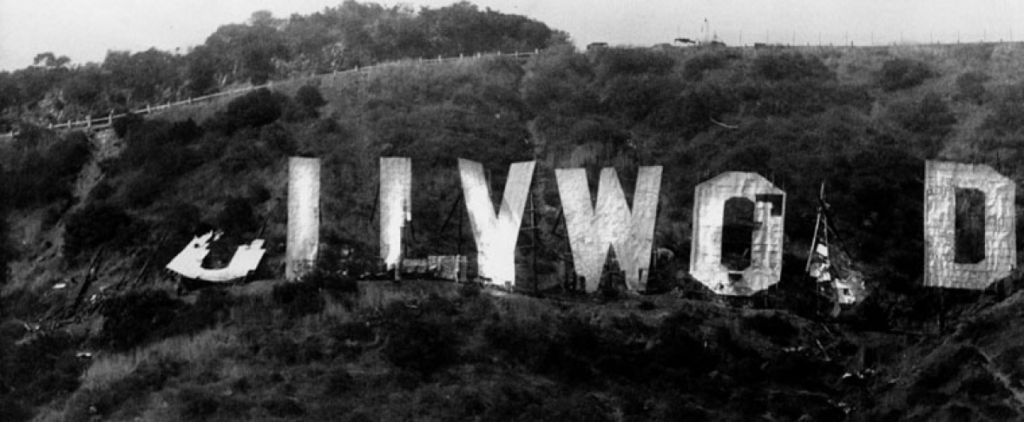

While American diplomats were being held hostage by the “students,” American reporters were still free to travel anywhere they wanted. The media had a field day with the crisis. One reporter gave Ayatollah Khomeini a highly respectful interview. Others filmed crowds of chanting Iranians and made man-on-the-street interviews. Evening news broadcasts had a daily counter showing how long the crisis had been going on; it ended up lasting 444 days. All of this added to a sense of unraveling and unease that had already been plaguing America in the 1970s. Argo alludes to this by showing the famous Hollywood sign in a state of disrepair.

[18]

[18]America in the 1970s was suffering from a sense of unraveling and unease. Even the famous Hollywood sign was in disrepair.

Leadership & Management Lessons

There are some considerable leadership and management lessons to be learned from the Iran Hostage Crisis. Mrs. Penelope Laingen launched a social movement with a simple yellow ribbon. She organized the families of the hostages and kept their plight in the national news headlines.

Then there is the fictional dilemma in the movie Argo where the President calls off the rescue mission because the Department of Defense says it has a plan to rescue the hostages in a commando raid. Jack O’Donnell orders Martinez to call off the mission, but he carries it out regardless. This is the fantasy that audiences love: the protagonist defying his boss and ending up a hero, anyway. In the real world, a middle manager such as O’Donnell would know the limitations of what he can do for a forward deployed agency in the field. He must push back against his boss in order to make sure he knows where the irrevocable decision points are. In some cases, once you launch, there is no going back.

Then there is Operation Eagle Claw [19], the ill-fated commando raid. The commandos were led by Colonel Charles Beckwith [20]. There was controversy within the Carter administration as to whether or not to go ahead with the rescue. It was not a case of groupthink, such as Kennedy’s decision to invade Cuba in the Bay of Pigs operation.

There were two very different schools of thought. Cyrus Vance [21], the Secretary of State, thought it was best to wait the situation out. The Iranians were likely to release the hostages eventually, since the longer they held them, the more costs they would incur on the international scene. The group that wished for an armed hostage rescue was led by National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski [22]. They made the case that a successful rescue would restore American prestige. Carter decided to back them — but it didn’t work.

One needs to be very aware of the limitations of military applications in most matters. There is no branch of the military more limited than the Special Operations Forces (SOF). I worked with Special Operations folks several times in my military career. One operation in which I provided a small amount of technical support worked swimmingly well. In other operations, which were training events where I worked with someone who had experience with SOF units, either as a Ranger or as technical/support troops, their ideas worked out poorly. In one case I was hustled by a Ranger to do something I thought was a bad idea, but decided to proceed anyway since it was going to be led by a Ranger. It didn’t work, and it caused me considerable embarrassment. The problem comes down to the fact that they have a “can do” attitude and many qualifications, but “can do” doesn’t always mean “should do.”

Operation Eagle Claw was such a disaster. Three of the helicopters carrying the soldiers turned back due to mechanical failures. The mission was so secret that information wasn’t passed along that should have been. Weather officers, for example, didn’t brief the pilots about the potential for dust storms. At the Desert One airfield, where the rescue choppers were to refuel, the noise from the engines made it impossible for anyone to hear. Nobody recognized their commanders, either, so there were arguments over who was in charge and whether one should follow orders from the random guy in black fatigues or not. When it was clear that the mission had to be aborted, one of the helicopters was caught in a gust of wind and crashed into another aircraft; eight Americans were killed.

Operation Eagle Claw was the final nail in the coffin of Jimmy Carter’s presidency. In the end, Iran released the hostages 20 minutes after Ronald Reagan was sworn in on January 20, 1981.

Iran paid a terrible price for the hostage crisis. The United States and Iran have complementary national interests. In the years since the Iranian Revolution, both nations have fought the same enemies, including Iraq, the Taliban, and ISIS. America and Iran also have terrible trouble with the Saudi Arabians. After 9/11, Tehran was the only capital in the Middle East where there was a spontaneous protest against the Salafi jihadists who had carried out the attack. The bitterness and suspicion between the two nations is such that generations may need to pass before there is a rapprochement, however.

Argo is a great film; a Right-wing film, even. It shows that decline is a choice. You can come back from degeneracy, but you need to work to do so. Professional excellence is important. It is clear that Martinez and the Hollywood insiders Siegel and Chambers knew their jobs and worked hard. It also shows the importance of thinking on your feet and recognizing what is important, as when O’Donnell calls Carter’s Chief of Staff to get the mission reapproved. Most importantly, it emphasizes the value of loyalty to your fellow countrymen.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[23]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[23]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.

Bibliography

Antonio Mendez & Matt Baglio, Argo: How the CIA and Hollywood Pulled Off the Most Audacious Rescue in History (New York: Viking Press, 2012)

Bruce Laingen, Yellow Ribbon: The Secret Journal of Bruce Laingen (McLean, Va.: Brassey’s (US), Inc., 1992)

Paul B. Ryan, The Iranian Rescue Mission: Why It Failed (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1985)