On Racial Humor

Posted By Spencer J. Quinn On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled [1]

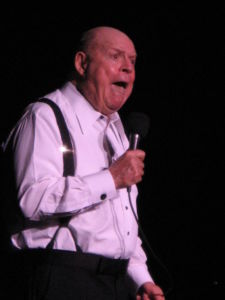

[1]Don Rickles. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons [2]

2,428 words

The 1970s and 1980s was an odd time for stand-up comedy. During this 20-year period, we saw the rise and glory years of what I would call racial humor. I define racial humor in this sense as jokes told by a racially aware comic that play upon or make fun of racial stereotypes. A comic can make fun of his own race just as easily as any other, but in all cases impresses upon the audience that his own race is one reason why the joke is funny to begin with.

A good example of this occurred during the Dean Martin roast of Muhammad Ali in 1976. Hispanic actor/comedian Freddie Prinze of Chico and the Man fame demonstrated the difference between a black fighter and a Puerto Rican fighter: He depicted the former by shadowboxing and the latter by pulling out an imaginary switch blade [3]. Not bad.

Richard Pryor had a better one when he recalled the time he tried to intimidate the owners of a Mafia strip club [4] with his militant blackness, and they just laughed at him and started telling murder jokes. Pryor was the one who ended up getting intimidated.

Eddie Murphy had an even better bit in his first comedy LP in which he made fun of black cowardice (or white quixoticism, depending on whom you talk to). Ronald Reagan had just been shot and one of his Secret Servicemen had taken a bullet protecting him. Murphy then proposed the (at the time) outlandish idea of a black Secret Service agent in Reagan’s entourage. While the silly white agents dive into a hail of gunfire, the black Secret Service agent sidesteps the scene and says, “Fuck that shit!” [5] He then starts thinking about getting a job at his uncle’s cleaners.

In the same vein, Chris Rock once began a joke by saying “Niggas have got to go,” [6] and then advised people who don’t want to get robbed to hide their money in books. “Books are like kryptonite to niggas,” according to Rock. Hell, everyone is a nigga [7] according to Dave Chappelle. He drops that word so often I wonder if he’d call the Pope a nigga if he ever met him.

None of these jokes would have worked had a white comic told them. All of them have a meta aspect to them because they depend upon the characteristics of the person telling them in order to be funny. And in all cases, they amount to a non-white comic poking fun at the very race he belongs to. We also have to keep in mind that jokes which compliment or flatter other races don’t count as racial humor because, while such jokes may be funny, they’re not edgy in the way that I feel racial humor must be. Here’s an example: two black guys are taking a leak off a bridge over a river. One says, “Water’s cold.” The other says, “Yeah. And deep.”

And tell me if you think fat black comic Bruce Bruce is flattering whites or denigrating blacks when he does a bit called “White people always pay on time.” [8]

This meta aspect is not unusual in comedy, and it doesn’t have to entail race. John Pinette [9] made brilliant use of his obesity. Brad Williams [10] currently gets tremendous mileage out of his dwarfism. Jackie Mason [11] did some good work ribbing Jews about their neuroticism. It’s almost to the point where if a comic does not match the white-straight-goyish norm, we expect him or her to clash comedically with that norm. Bill Cosby and Jerry Seinfeld rarely do this, but George Carlin, white-straight-goy that he was, did. In his early years, he derived much of his comedy from clashing ideologically with these norms. And boy, did he wear that on his sleeve. That’s what his seven-words-you-can’t-say-on-television [12] bit was all about. He was counter-culture, man. Like Lenny Bruce! He was funny! But he still had to keep expanding that list to prevent it from going stale, because as the norms changed, so did the humor. And he never did include the word “nigger” in that list. So much for being edgy.

When I was a kid I saw a black male comic on some improv program. I was a little shocked, because in his eight-minute routine he never once told a joke about race — and he wasn’t Bill Cosby. He was funny, but not that funny.

For white comics, this kind of racial humor is taboo — and not just because of our woke Leftist overlords. White complacency is another reason. Most white Americans, God bless ‘em, still believe they are in charge around here. They still believe that America is their country and that they represent the norm to which the lucky ones assimilate and from which all others deviate. To make fun of whites as whites wouldn’t be funny to them because they see themselves as the normal ones. What’s funny about that? (And here’s 18 minutes of Bill Burr [13] trying to answer that question and failing; don’t click if you hate to see a white man cucking shamelessly to blacks.)

On the other hand, a white comic making fun of other races in more than just a passing, light-hearted manner would smack of spite to whites and elicit unwelcome feelings of guilt and anxiety. It’s one thing to crack an off-color joke about basketball and rape [14] when you’re with your buddies after having a few beers. That’s a guilty pleasure. But a white person making it his thing to denigrate non-whites onstage would be cringe city. Most whites would view it as punching down, and most blacks would view it as grounds for punching back. Today, such a move would be a career-ender. Just ask Michael Richards after his fiasco at the Laugh Factory [15] in 2006. His career never really recovered. Thus, whites are almost universally banned (and self-banned) from racial humor.

Yes, Andrew Dice Clay got away with mocking Indian immigrants [16] — but that was decades ago, and in the version I saw on television, he pointed to the one black guy in the audience and announced that he was down with the Bloods just to prove how non-racist he was. (Clay is Jewish, I know, but his leather jacketed, chain-smoking greaser look, combined with his foul mouth and over-the-top misogyny, was very goyish.) These days, white roasters can make snarky comments on some of the milder black peccadilloes — being loud, being late, liking waffles and fried chicken, that kind of thing — just as long as they’re prepared to grin and bear it when some non-white comedian joshes them back about being a closet Nazi or a dumb, inbred, meth-addicted, trailer-trash hayseed. This latter crack was actually made at the roast of Jeff Foxworthy [17] in 2005, and some of the barbs lobbed at Ann Coulter at these roasts are just hatefully anti-white [18]. Not exactly a balanced relationship, is it?

[19]

[19]You can buy Spencer Quinn’s novel White Like You here [20].

And here’s black comic Tony Rock telling us about the “whitest thing he ever saw.” [21] Is anyone offended by this? I wasn’t, even though it was probably meant to offend a little. If blacks wish to compare themselves unfavorably to whites when it comes to maintaining order in a civilized society, that’s fine. It’s true, after all, even if Rock thinks he’s making white people look bad with his ghetto jibes. But still, the double standard exists. Black comedians can get away with things that white comedians can’t.

Not that I’m complaining. Funny is funny, and humor cannot be forced. Today’s society is what it is; if comedian A cannot tell joke B because he belongs to race C, then so be it. In some ways humor is like magic: It just appears, and if people laugh, you have to respect it. But what’s less and less magical these days is racial comedy from whites.

This brings me back to the racial comedy heyday of the 1970s and ‘80s, and the one non-black comedian who could play on any race and any ethnicity and still get laughs. Of course, I’m talking about Mr. Warmth himself: Don Rickles.

Rickles was a consummate entertainer who’s razor-sharp wit [22] never stopped rendering the funny from whatever was around him. He was inhumanly quick in conversation and would have six or seven pointy little zingers all coiled up in his bullet head ready to go before Johnny Carson [23] or Dick Cavett [24] or whoever could muster a response to the last time Jewish Buddha had smashed his face in with an insult — that is, if he could stop laughing long enough even to speak.

Rickles basically had three things going for him: comedic genius; a truly benign, catholic outlook; and unshakable optimism. The first is self-evident, and when measured against his peers, from his day to ours, he really was the best at all the racial stuff. And he did it without going blue. I wish Jeff Ross and other modern roasters would do the same, but even if they did, they could still never match the Don for the plethora of rhythms, intonations, and accents [25] he had swimming around in his mind like ugly mermaids. He really could sound black or Jewish or whatever he wanted to sound like. Rickles’ racial awareness came from his catholic outlook. He wasn’t just another Jewish comedian from the Catskills; he really did love everyone, and so he wanted to appeal to everyone. And that meant, for him at least, that he got to make fun of everyone. The harder he hit you, the more he loved you and the more you laughed. To hell with racial pride. It was an honor to be insulted by the Merchant of Venom.

We should note that while he would broadly (and unflatteringly) caricature blacks, Jews, Hispanics, and Asians, he rarely if ever did so with whites. He instead took aim at the Irish, Italians, Germans, or Poles. Onstage, whites were all petty nationalists to him. Once on Saturday Night Live, he inquired about the ethnicity of an audience member When the man said he was Norwegian, Rickles announced in consternation that he didn’t have a joke for Norwegian — and that, of course, was the joke. Despite being a Democrat, I’m sure he respected white people (he got a few yucks [26] at the Republican National Convention in 1984, after all), but in his act white people were usually absent, which meant that they were rarely if ever mocked, teased, or in any way dragged through the ringer like everyone else was. Maybe that’s one reason why I always liked him.

It’s interesting to compare Rickles with Jimmy Durante, a comic I would describe as the anti-Rickles. Like any funny Italian, Durante had a big nose, but his was really big and shaped like a rotten onion. He called it his “schnozzola,” and he said that as a kid he always hated it when people made fun of him for it. So in his professional career he vowed never to make fun of people for their personal defects (Eddie Murphy made this point quite forcefully [27] to a very young Dave Chappelle in The Nutty Professor). This is neither bad nor good in terms of comedy, but it results from a profound lack of optimism. Because insult jokes hurt him, Durante was not optimistic that insult humor wouldn’t hurt others, and so abstained from it entirely.

Rickles, on the other hand, was brimming with such optimism. He assumed everyone could take a joke. He assumed everyone would gleefully absorb personal and racial abuse and not want to smack this motormouthed Jew in his pink, jowly chops. And somehow, this comic genius (at least in the 1970s and ‘80s) always knew what line to never cross. He always stayed on the funny side of that line.

Except for one time.

During the roast of Dean Martin in 1974, Don Rickles annoyed Muhammad Ali [28]. I’ve seen hours of Rickles’ material on the Internet, and nowhere else did anyone ever get annoyed with Don Rickles. Ali was trying to say something nice and insulting to the seemingly inebriated Martin, as one is wont to do at a roast, when Rickles horned in on their discussion with some downhome black talk. Ali tried to play along, but Rickles was too in the moment to understand that he was about to cross a line. He was crowing incoherently like an obsequious step ‘um-fetch ‘um about living in Memphis and driving a school bus. Who knows why this was funny? It could have been a reference to something topical that’s lost on us today. In any event, in a fascinating exchange Ali asked Rickles if he stole, and Rickles responded like a toadying slave, “No way, Muhammad. Unless you say so. Anything you say, I do.”

His delivery was so over the top — and so spot on black — that Ali asked him quite seriously why he had to talk like that. You know Ali was serious, because for a split-second Don Rickles did something he never did: He broke character. The Merchant of Malice himself stared into that fourth wall and abandoned kayfabe. He said, almost under his breath, “It’s just a put on.” That is, it’s not real. I kid you because I love you, Bubbie. That kind of thing. But Ali was too annoyed to listen. Instead, he challenged Rickles to speak the same way to other people, such as Italians.

And here, Rickles’ wit saved him. “No, no,” he responded, still in blackface. “I never talk in front of them. I tap dance!”

To roaring laughter, Ali walked away from the lectern with a look of chagrin on his face. What else could he do? He was a witty guy for a prizefighter, but he was no comedian. Comedy is magic, and you have to respect it.

But this forgotten, 50-year-old exchange can tell us a lot about racial humor and how much of it blacks will tolerate when they’re the butt of it — that is, very little. I don’t care how hilarious Nipsey Russell and Sammy Davis, Jr. found this kind of humor back in the day. Most blacks don’t like non-blacks making fun of them; it reminds them of their own inferiority and enflames their insecurities, insecurities that become malignant with their proximity to whites.

50 years ago, blacks did not have the political clout to police non-black racial humor, which is why Don Rickles still had a job after his encounter with Ali — his tremendous talent notwithstanding. These days, however, things are different. Blacks do have the clout now, and they use it — and racial comedy is dying as a result.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[29]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[29]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.