“Many Strange & Terrible Days”: Gothic Science Fiction & Modern War, Part 2

Posted By Kathryn S. On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled4,699 words

Part 2 of 2 (Part 1 here [2])

II. Out of Space: Fever

The thickened present manifested also in both a more expansive and a more constricted space during Gothic Science Fiction wars. The spread of poisons — rumors, gasses, the encircling anaconda-enemy, and diseases — began to intoxicate those trapped within their towns and trenches. The frenzied pace of emotional highs and lows gave way to gradually spreading fevers, for within a siege, everything became an epidemic. Armies themselves were bodies riddled with infection that also spread this infection to the bodies of its constituent members — in the form of bad morale and actual debilitating pathogens. Of course, they moved and passed through towns and countryside, infecting the civilian bodies who lived there as well.

As Wells’ Martians moved with impunity about the world, conquering as they went — terrifyingly expansive in their reach –, their victims felt their own worlds shrink; the enemy drove them underground and below in subterranean caverns like rodents on the run. They hid and tried not to breathe too hard or too often from air they once gulped freely like they had fresh river water. The aliens “discharged, by means of the gunlike tube[s] [they] carried, a huge canister over whatever hill, copse, [or] cluster of houses” they came upon. These canisters smashed upon striking the ground, then released into the atmosphere an “enormous volume of heavy, inky vapour, coiling and pouring upward in a huge and ebony cumulus cloud, a gaseous hill that sank and spread itself slowly over the surrounding country.” A slight touch or accidental inhale of its “pungent wisps, was death . . . It was heavier than the densest smoke,” sinking down “through the air and pour[ing] over the ground in a manner rather liquid than gaseous, abandoning the hills, and streaming into the valleys and ditches and watercourses even as . . . [the] carbonic-acid gas that pours from volcanic clefts is wont to do.”[1] [3] So much space and so much claustrophobia in one, single image!

It must have been something like what Southerners would have perceived when they left places like “Nashville . . . bowling along twenty or thirty miles an hour, as fast as steam could carry [them]” toward the front;[2] [4] or when they watched the ironclads, the most Gothic science-fictional-looking invention of all time, that could roam along the coasts at will, ramming and bombarding wooden ships to splinters. One could travel a long way in those impervious, metal-plated monstrosities, but while doing so, one was encased as in a tomb, breathing in smoke fumes and, often enough with the ironclads, water for his final lungful.

And as the North closed in like a noose around the South, choking off its waterways by vast and gradual degrees, the Southerner “soon became ‘utterly cut off from the world.’”[3] [5] On February 25 of 1863, Mrs. Miller of Vicksburg journaled that her husband had “been ill unto death with typhoid . . . and [she had] nearly broke[n] down from loss of sleep.” Never before had she realized how terrible the starless night could be for a woman alone and “with a patient in delirium, no one within to call.” Meanwhile, she related, “the Federal fleet [had been] gathering, [had] anchored at the bend, and shells [were] thrown in at intervals.” Nearly one month later and “[t]he slow shelling of Vicksburg [was going] on all the time, and [she had] grown indifferent.” Authorities ordered non-combatants to leave or to prepare accordingly. Those who had decided to remain had caves built.

Cave-digging, Mrs. Miller explained, had “become a regular business; prices range[d] from twenty to fifty dollars, according to size of cave. Two diggers worked at [hers for] a week and charge[d] thirty dollars” for it. According to her estimation, the makeshift shelter was “well made” and burrowed “in the hill that slope[d] just in the rear of [her] house, and well propped with thick posts, as they all [were].” Despite this craftsmanship, she described living in it as having an unbearably “earthy, suffocating feeling, as of a living tomb, [which] was dreadful to [her].” At some point, she feared she would go mad and “risk death outside rather than melt[ing] in that dark furnace.” All the hills were “so honeycombed with caves that the streets look[ed] like avenues in a cemetery.” I live, she wrote, in a “casket.”[4] [6]

Half a world away and seven years later, the lightning-quick movement of the allied German army had resulted in Paris besieged. By encircling the city and her residents, the war turned an already volatile city at the best of times into an insane asylum. An English war correspondent within Paris admitted that “the gaudiness of the early days left a vacuum which was beginning to be occupied by something dangerously like boredom; dangerous, because Paris knows no more promising incubator of revolt and kindred diseases than that most dreadful of states, l’ennui.” By October 21, 1870, more than a month since either side had made any “major action,” all within were beginning to grumble among themselves. What the siege was beginning to mean “to a sensitive and intelligent Parisian was

To live within oneself, to have no other exchange of ideas than something as undiverse and limited as one’s own thought, rotating around one obsession; to read nothing but thoroughly predictable news about a miserable war . . . to enjoy modern life no longer in this early-to-bed city . . . thus is the Parisian imprisoned in Paris by a boredom comparable to that of a provincial city.[5] [7]

In other words, Paris had become like everywhere else in France, and it was intolerable. A lack of news from outside became “a worse privation even than the subsequent food shortage, and it soon revealed itself as a most pernicious psychological factor, operating on a multiplicity of levels.” One immediate result of the news blockade “was a plethora of incredible rumours, which, since no one could refute them, the Paris Press printed with avidity.”[6] [8]

[9]

[9]You can purchase Tito Perdue’s novel Though We Be Dead, Yet Our Day Will Come here [10].

Like those in Vicksburg before them, everyone seemed to be engaged “in measuring the distance from the Prussian batteries to his particular house.” The writer found one friend “seated in a cellar with a quantity of mattresses over it, to make it bomb-proof. He emerged from his subterraneous Patmos to talk to [him], ordered his servant to pile on a few more mattresses, and then retreated.’”[7] [11] Others dug tunnels and clustered together in underground sewers. As in all claustrophobic environments engendered by the dictates of a Gothic science-fictional war, alongside these small passageways and narrowing halls were tales of awesome reach.

In order to bypass the siege, to send and receive mail, Parisians launched a fleet of pigeons and hot-air balloons. Two engineers went up in their balloon one day, then found themselves blown off-course, finally landing in an alien land where none spoke a language they recognized. It was not until one of the peasants whom they approached “lit a fire with a box of matches marked ‘Christiania’ that [they]realized that they had landed in the centre of Norway!” In the span of 15 hours, “they had travelled nearly nine hundred miles from Paris; it was a voyage worthy of the imagination of Jules Verne!” The “aeronauts” were taken to “Oslo (then called Christiania), fêted by blonde young women draped in tricolores and banqueted for several days like visiting gods, then returned home.”[8] [12]

The rest of Paris had to stew in a growing incestuous atmosphere, warm like soup. Along with imbibing too much alcohol and not enough nutritional calories, many were beginning to indulge in the headier wine spouted and passed carelessly around in the popular “Red Clubs”: hot-beds of radical thought, whose pamphlets were beginning to be the only newsprint a Parisian could reliably get hold of. The result would be the short-lived Commune — one of the most disastrous and bitter episodes in French history (which is saying something). It was the toxic flower that bloomed from a soil starved of clean oxygen and nourished with the filth in which a particularly nasty modern siege forced Parisians to wallow.

So much for Paris and Vicksburg, but has there ever been a more gothically science-fictional war than the First World War? Look at the picture below, readers. If this was not one of the most iconic images of the Great War, you might assume that it was taken from a film set meant to dramatize a conflict on another planet. No war was more suffocating than this one, with its underground fortresses, tunneled trenches, quick-sand mud traps, gas attacks, and the masks that tried to neutralize their effects. Gas attacks killed relatively few people, but the fear of them affected nearly everyone at the front, a fear that spread like the toxin itself.

Englishman Edmund Blunden described the diffusion of chlorine as a “white mist (with the wafting perfume of cankering funeral wreaths),” which quietly and deceivingly worked “its way above the pale grass.” While more and more bullets flew “past the white summer path . . . some cracking loudly like a child’s burst bag, some in ricochet from the wire or the edge of ruins groaning as in agony or whizzing like gnats,” he walked the due road and “saw what looked like a rising shroud over a wooden cross in the thick mist.” For a moment he felt an absolute “Horror! but on a closer study, [he] realized that the apparition was only a flannel gas helmet spread out over the memorial.” When such mist lay “heavily in the moonlight” within a “silence and solitude beyond ordinary life,” the result was “fantastic. It was all a ghost story.”[9] [14] There was allure in horror.Ernst Jünger’s recollections were also poetic, but rawer in their immediacy. When the “Suffocating gases hung in the undergrowth,” he wrote, “dense vapour wrapped the tree tops, trees and branches came crashing to the ground, [and] loud cries rang out. We [all] jumped up and ran wildly, hunted by lightnings and stunned by rushes of air.” It was like a hurricane of toxic fumes — one that felled trees and scythed through lungs. Over the town of Monchy, “there rang out the long-drawn cry, ‘Gas attack ! Gas attack !’” Over the buildings rose “A whitish wall of gas, fitfully illumined by the light of the rockets.” The next morning afforded his company the opportunity “of marvelling at [its] effects . . . Nearly every green thing was withered . . . and any despatch-riders’ horses that were in Monchy had water running from their mouths and eyes. The ammunition and the shell splinters that lay everywhere were covered with a beautiful green patina.”[10] [15] Once again, there was a strange attraction – even beauty – in the awful. Men who wore and then walked abroad in their gas masks, their “respirators,” with “bayonets glistening,” seemed to have “a large snout in front . . . they looked like some horrible nightmare” out of the imagination of H. G. Wells.[11] [16] Whether besieged by mortar, vapor, or the cloying sightlessness of a mask, all innovations of the scientific mind, there was the pervasive feeling of having been consumed by fever, or buried alive — the most common trope in Gothic literature. Fitting, then, that Wells’ Martians themselves ultimately succumbed to a bad case of the sniffles.

III. Overcome: Mutation

Even after the Martians had all died to a man (if alien), they left behind them a different world. Because “the vegetable kingdom in Mars, instead of having green for a dominant colour, [was] of a vivid blood-red tint . . . the seeds which the Martians . . . brought with them gave rise in all cases to red-coloured growths.” That known popularly as the red weed, or red creeper, “grew with astonishing vigour and luxuriance. Its cactus-like branches formed a carmine fringe to the edges of [the narrator’s] triangular window. And afterwards [he] found it broadcast throughout the country,” all the way down to the “river below,” which became a “bubbly mass of red weed.”[12] [17]

Though the war had ended and something approaching “normal” life had begun once again to fill the holes and craters, still the narrator would sometimes watch from outside his window “a butcher boy in a cart, a cab-full of visitors, a workman on a bicycle, children going to school, and suddenly they [would become to him] vague and unreal.” On some nights he recalled “the black powder darkening the silent streets, and the contorted bodies shrouded in that layer; they [rose] upon [him] tattered and dog-bitten. They gibber[ed] and [grew] fiercer, paler, uglier, mad distortions of humanity at last,” and he would “wake, cold and wretched, in the darkness.” On trips to London, he would observe the busy multitudes walking down “Fleet Street and the Strand, and it [would come] across [his] mind that they [were] but the ghosts of the past, haunting the streets . . . going to and fro, phantasms in a dead city, the mockery of life in a galvanised body.”[13] [18]

The most important element in Gothic Science Fiction is that of contaminated bodies, both in terms of literal bodies and of landscapes/geographies — the terraforming and mutations that occur because of war, because of alien contact. Within this sub-theme there is woven the interpenetration of space-time, a merging of past and future into a thickened present of “becoming.” The ancient and futuristic combine to create something eerie and unsettling in its “un-deadness”: sarcophagi, dis-assembled bodies of zombie-figures, old forests filled with new nightmares, weathered spaceships circling their old orbits, the Wild West paired with robots and clones, the dingy castle-basement of a mad scientist, thousand-year-old cities reduced to ruins in a fortnight — all of these Gothic science-fictional examples marry birth and death. The consigning of humanity into both a dead past and a horrible coming-into-being of some new life is one and the same thing in this special genre. Death is not the true horror — but not-dying certainly is.

In all three wars discussed here, soldiers and civilians used classical and sometimes medieval allusions to talk about the surreal beginnings and consequences of industrial warfare. As all of Charleston lay in the grip of mad war-euphoria during the shelling of Fort Sumter, one Charleston lady remarked that her gentleman-friend Langdon Cheves was “forced to go home and leave this interesting place.” The disappointment apparently made him feel left behind, as if he were “the man [who] was not killed at Thermopylæ . . . Maybe he fell on his sword, which was the strictly classic way of ending matters,” she mused wryly. In the South, “we do not need to be fired by drink to be brave,” for fire was in the Southern blood. “I faintly remember,” she wrote, about the Spartans “who marched to the music of lutes. No drum and fife were needed to revive their fainting spirits. In that one thing, we [were] Spartans.”[14] [19]

Four years later and the South looked like the ruins of an ancient civilization, but twisted with the weird new, industrial landmarks known as “Sherman’s Neckties” and husks of cities, factories, mills, and houses so burnt-out that their locals referred to these places as “Chimneyvilles.” Superheated iron rails were wrapped around trees, rendering the landscape grotesque – a literal binding to symbolize the metaphorical bondage of the defeated South. The whole region had been maimed, and “the impact upon its [crippled] spirit and emotions could not be overstated.”[15] [20]

All along the busted tracks and dusty roads, walking soldier-zombies straggled from the front to wherever they had once called home before the war: an inverted, bitter, and often just as dangerous version as that odyssey taken by Homer’s hero thousands of years earlier. One hard-pressed rebel from Texas claimed that he “suffered more hardships and trials and experienced more dangers after the war had ended and peace had been declared than [he] had ever encountered during the four years in the field.” At night while crossing the backcountry of Missouri, he took care to sleep “on high eminences in order that [he] might watch for scouring search parties who were shooting down in cold blood every man that wore the Southern uniform, and for no other reason.”[16] [21]

Everywhere, “desolation met our gaze,” said one infantryman returning to Arkansas. He watched as “half starved women and children; gaunt, ragged men, stumbling along the road . . . [tried] to find their families, wondering if they had a home left.” His own home was unrecognizable due to having been beaten down by the feet of “hostile armies . . . all the horrors and devastations of ruthless war” he traced in its “ruins, blood, and new-made graves.”[17] [22] The rotted wharves on the Mississippi had meanwhile all decayed and dissolved into the water. Steamboats lay half-sunk and wrecked — ugly hulls that blocked any navigation on the streams and inland bays of Arkansas. When Sara Rice Pryor of Petersburg, Virginia could finally go back to her farm, she found the same thing: The earth about her property had been “ploughed and trampled, the grass and flowers were gone, the carcasses of six dead cows lay in the yard, and filth unspeakable had gathered in the corners of the house.” Worse was the smell, for “the very air was heavy with the sickening odor of decaying flesh. As the front door opened, millions of flies swarmed forth. . . . Pieces of fat pork lay on the floors, molasses trickled from the library shelves, where bottles lay uncorked.”[18] [23] These Southerners were home and not-home; a part of them had died, and yet they had no option but to go on living in this mutated place, in this alien landscape where they had become something new and unwanted as well.

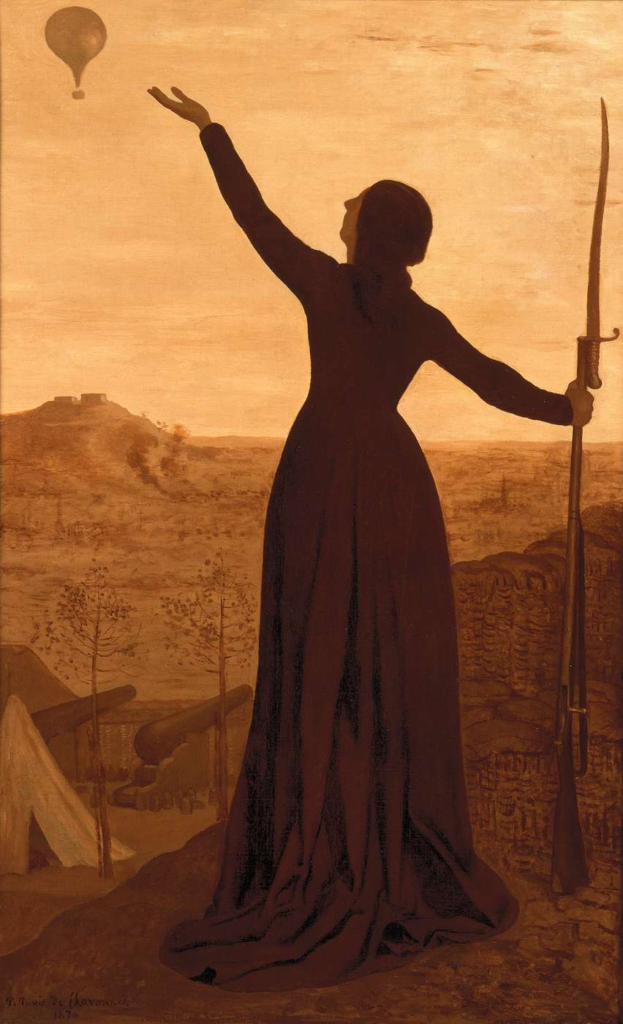

The above piece could have been 1865 Petersburg. Instead, it is . . . what is it? Something caught between modern and Middle Ages. I see a woman dressed in mourning weeds that might be a nineteenth-century frock, or a twelfth-century habit; a dark slash across monochrome beige. She appeals upward, as if to God in heaven, but actually (also?) to a flying balloon. The landscape around her looks like a wasteland — struck by medieval pestilence or industrial war. Are the two trees, whose limbs creep up delicately, from a Giotto fresco? But we see another, stronger tree rise to the right: a bayonet-tipped rifle, taller than she, juts high into the foreground. The shells sit crowded and stacked beside their heavy mortars below. This piece is of a shrouded and anonymous Joan of Arc with a Needle Gun; an embattled Marianne willing her soldiers aid from behind the parapets, her prayers sent on the wing; the past and future making something else altogether.

Besides being known for losing the Franco-Prussian War and ending the French imperial dynasty for good, Napoleon III was famous for boasting that he would be “a second Augustus . . . because Augustus made Rome a city of marble.”[19] [25] So he cleared out the old, dingy parts of Paris and its narrow little alleys, then widened the avenues into splendid boulevards (which later came in handy when the Prussians desired to march beneath the Arc de Triomphe in large, extended formation and into the shell-shocked city). But by the end of May 1871, the city presented a terrible sight. In the Place de la Concorde, “the Tritons in the fountains were twisted into fantastic shapes; the candelabras torn and bent; the statue of Lille decapitated . . . the Rue de Lille, on the Left Bank seemed to be deserted throughout its length, like a street of Pompeii.” A Roman city-street, all right!

Over these ruins “a silence of death reigned,” as if Parisians now lived in “the necropolises of Thebes or in the shafts of the Pyramids.” At the Hôtel de Ville, there was “a certain Gothick romanticism and beauty about the ruins.” An immense heat had “imparted to the stone and the metal the most exotic colours; All pink and ash-green and the colour of white-hot steel, or turned to shining agate where the stonework has been burnt . . . it look[ed] like the ruin of an Italian palace.” Nearby, the Communards had toppled the column where a large statue of “the Great Emperor” had stood previously, while “members of the crowd [had] rushed up to spit on” his remains. It all reminded one reverend of his visit to ”the shapeless ruins of Memphis,” when he stood beside a broken and “prostrate statue, probably that of the great Rameses.”[20] [26] It was this strange meld of medieval and modern, ancient and industrial ruin that made Paris appear so gothically science-fictional after the Communards had fallen and the treaty at Versailles was signed.

[27]

[27]You can buy Greg Johnson’s Graduate School with Heidegger here [28]

The surrounding country fared no better, and sometimes even worse. On the Prussian side, observing Lieutenant General Philip Sheridan, a veteran of the Civil War and one of William Sherman’s acolytes, had advocated for a new thing called “total war.” In his estimation, the German army had not been harsh enough. He had advised Bismarck to cause the French “so much suffering that they must long for peace and force their government to demand it. The people must be left with nothing but their eyes to weep with over the war.”[21] [29] Yes, readers, Sheridan had accused the Prussians of being too soft. A scary man — and this at a time when Parisians and those in the suburbs were reduced to eating rats and sawdust cakes.

A correspondent remembered that friends of his, a French colonel named Heintzler and his wife, had been throwing a breakfast party at their recently acquired outpost of Avron. During the brunch, the party was suddenly “spoiled by a heavy Prussian shell which burst without warning in the room.” Six of the breakfasters were killed outright, “the host and hostess were gravely wounded, and only the regimental doctor and a servant [had] emerged unscathed.” Two days later, the writer visited them in hospital and saw “the remains of the victims,” both living and dead, “but it was [all] such a human ruin that no individuality could be recognised”[22] [30] — perhaps because little at last separated the survivors from the slain, shelter from ruin, when it came to Sheridan’s kind of “total war.”

If the land and the people on it had been irrevocably overcome by desolation in France and the South, then in some ways and sometimes it must have been overcome, too, by its strangeness and even its beauty. The single most striking and fantastic film scene that I have watched over the past decade was that of 1917’s nighttime sequence spanning past and alongside the Great War’s ruins, alternately lit and shadowed by the glare of rockets and the licking of their secondhand flames. The protagonist crosses this alien landscape while on his way to warn a nearby army against the next morning’s scheduled attack. As the machines had in the Serbian office at the beginning of the war, the electric telegraph system at the Front had broken down, and the only wires working were those that were barbed and spun by hand across the landscape, like bloody needles and thread. This is to be a mission completed by man, not by the machines that made his mission so perilous and necessary. Above him the sky is “dark and fabulous,” set off against the rumors of houses and cathedrals by the occasional crack of mortar fire. Now and then “a single shot [rings] out, or a rocket [fizzes] up and after a brief and ghastly illumination left the darkness blacker than before.” It is a storm like one might see on Mars or farthest Pluto, beautiful and terrible.

Of the three wars, the First World War left the most lasting scars, visible and invisible, on both psyche and landscape. When out among these fragments, “You [were] aquiver with two violent sensations,” Jünger wrote: “the tense excitement of the hunter and the terror of the hunted. You [were] a world in yourself, and the dark and horrible atmosphere that brood[ed] over the waste land . . . sucked you in utterly to itself.”[23] [31]

Boys had gone off to war filled to the gills with “the whole gamut of culture from Plato to Goethe.”[24] [33] By 1917, poet Wilfred Owen could famously and bitterly repeat: “Dolce et decorum est pro patria mori.” It wasn’t just the aged men still living whom the author blamed, but every generation of aged men before him, every one of them who repeated that “old [Roman] lie,” as he saw it. Others were not quite as bothered by the Classics, but they too recognized that all had changed and that the old ways of viewing the world had changed, that they had changed; that the old in general seemed more remote than ever. There was the “impression of something arising entirely from beyond the pale of experience,” so strange that it was “difficult to see the connection of things. It was like a ghost at noon.”[25] [34]

Yes, around them loomed many ancient ghosts. Climbing up a “vineclad ascent, and on reaching its summit,” a company of soldiers saw lying before them the “beautiful valley of Moselle and the white chateaux on the farther slope . . . On the left the grim old ruin of the Castle of Mousson frowned from the top — a gaunt skeleton of ancient war, looking down upon modern War. . .” A few of the villagers walked about in a “ghostly fashion” by the “historical old cathedral.” The tint of blood where “the unburied dead yet festered in the sunheat” lingered there amidst the smoking and stinking ruins of Bazeilles.[26] [35] Overall was a feeling of “unreality” that oppressed Jünger as he continued his march and “stared at a figure streaming with blood whose limbs hung loose and who unceasingly gave a hoarse cry for help, as though death had him already by the throat,” another of the halfway human, torn and shattered men whom the war had left behind to linger in their twilight agony. A soldier in such strange circumstances retained “only the spell of primeval instinct,” and not till “blood [had] flowed” did the mist give way “in his soul. He [then looked] ‘round him as though waking from the bondage of a dream.”[27] [36]

It was late when he and his troop at last “left the trench and went in the warm evening air by the footpath winding over the undulating ground. Dusk was so far advanced that the red poppies in the untilled fields blended with the vivid green grass to an extraordinarily rich tone.”[28] [37] The flowers were an ancient symbol of sacrifice, used in the Aeneid and in Homer’s Iliad to describe a youth as he “roll[ed] over in death,” but not-death, as “over his beautiful limbs gore flow[ed] . . . just as when the crimson flower, cut down by the plough droops as it [falls], or poppies with weary neck lower their heads, when they are weighed down by a chance [rain] shower.”[29] [38] Thus were drops of blood turned to blooms and death into another way of living, red like the “lowered heads of poppies,”; red like the communard’s flag and final wage; red like the weeds of Wells’ strange new world as they crept toward the river.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[40]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[40]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.

Notes

[1] [41] Wells, 137.

[2] [42] Sam R. Watkins, Co. Aytch (Chattanooga, Tenn.: Chattanooga Times, 1900), 14.

[3] [43] G. O. W. Cable, “Preface” in Vicksburg: 47 Days of Siege (A. A. Hoehling, Stackpole Books, 1969), iii.

[4] [44] Dora Miller, Vicksburg: 47 Days of Siege (A. A. Hoehling, Stackpole Books, 1969), 20-1, 36, 45.

[5] [45] Sir Alistair Home, The Fall of Paris: The Siege and the Commune (New York: Penguin, 1965), 46.

[6] [46] Ibid., 126.

[7] [47] Ibid., 124.

[8] [48] Ibid., 195.

[9] [49] Edmund Blunden, Undertones of War (New York: Doubleday, 1929), 50.

[10] [50] Storm of Steel, 92-4.

[11] [51] Erich Maria Remarque, All Quiet on the Western Front [52], 33.

[12] [53] Wells, 204-5.

[13] [54] Ibid., 292.

[14] [55] Mary Chesnut, Diary from Dixie (New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1906), 37, 205.

[15] [56] Thomas & Debra Goodrich, The Day Dixie Died: Southern Occupation, 1865-1866 (Mechanicsburg, Penn., 2001), 231.

[16] [57] Lucas Collection, loose clippings, folder #103, Sherman, Texas, Public Library.

[17] [58] Mark K. Christ, Rugged and Sublime: The Civil War in Arkansas (Fayetteville, Ark.: University of Arkansas, 1994), 160.

[18] [59] Sara Agnes Rice Pryor, Reminiscences of Peace and War (New York: Macmillan, 1906), 283, 294.

[19] [60] Mary McAuliffe, Dawn of the Belle Epoque (Plymouth, UK: Rowman & Littlefield, 2011), 12.

[20] [61] Fall of Paris, 521, 450.

[21] [62] Stephen Badsey, Essential Histories: The Franco-Prussian War (London: Osprey, 2006), 53.

[22] [63] Fall of Paris, 271.

[23] [64] Storm of Steel, 36, 70.

[24] [65] All Quiet on the Western Front, 12.

[25] [66] Storm of Steel, 3.

[26] [67] Undertones of War, 260.

[27] [68] Storm of Steel, 263.

[28] [69] Ibid., 160.