Fail-Safe & Today’s Nuclear Crisis

Posted By Steven Clark On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledUnlike many moviegoers, I was never that enthusiastic about Dr. Strangelove, Stanley Kubrick’s response to the arms race. I remember that back in the 1980s, a girlfriend and I saw the film and she thought it made light of a serious issue. This was at the height of President Reagan’s sending more missiles to Europe, his Star Wars missile defense plan, and everyone’s lugubrious viewing of The Day After.

In Anthony Burgess’ autobiography, You’ve Had Your Time, he analyzes Dr. Strangelove:

Dr. Strangelove was very acerbic satire on the nuclear destruction we were all awaiting. Kubrick caught in a kind of one-act play, trimmed with shots of mushroom clouds, the masochistic reality of dreading a thing while secretly longing for it. I felt, though, that he over-valued the talent of Peter Sellers and made the tour de force of his playing three very different parts in the same film obscure the satire by compelling technical admiration.

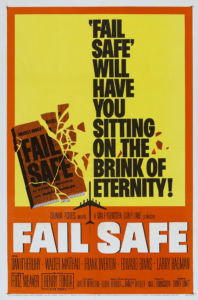

A reason I also found Dr. Strangelove lacking was when I compared it to Fail-Safe, a 1964 film which took a serious, almost tragic view of what Kubrick had satirized.

Sidney Lumet’s film was adapted from the book by Eugene Burdick and Harvey Wheeler, and having read it, it is faithful to the printed word. Where Dr. Strangelove is exaggerated and grotesque, Fail-Safe is chillingly normal. The term refers to the procedures the military follows to prevent accidental nuclear war and, like other military terms such as Zero Defects, implies control over any kind of human infallibility.

But what about machines?

A normal day begins in an abnormal way for General Warren “Blackie” Black (played by Dan O’Herlihy). He dreams of a bullfight in which a matador kills the bull. He wakes up, finding himself on his way from New York to Washington, where an important conference is being held. He is to receive a new member of the defense establishment, Professor Groeteschele (Walter Matthau).

While Black had an uneasy sleep, Groeteschele is winding up an all-night party in Georgetown, keeping the guests spellbound as he almost cheerfully describes the possibility of winning a nuclear war. Groeteschele was modeled on Herman Kahn, an actual nuclear strategist who believed in the concept of winnable nuclear war, and Matthau is coldly perfect as a merciless academic, confidently pointing out that the best survivors of a nuclear war would be convicts and file clerks, and that from these two would begin a new civilization. He brushes away concerns about universal destruction. There would, Groteschele cannily observes, be only victory for one side and defeat for the other.

It’s apparent that he hopes for an American victory. He considers the Russians to be barbarians who must be defeated. Matthau is masterful as the cold and confident academic, a Jewish chess master clearly in charge of the party. Where the character of Dr. Strangelove is at once creepy and hilarious, Groeteschele’s eyes and pouchy face resemble a predator stalking its prey, waiting for the chance to prevail. He is scholarly but also has a magnetic appeal to the spellbound partygoers. Among them is Ilsa Wolfe (Nancy Berg), a sophisticated party girl who thoughtfully smokes as she studies him. The party ends at daybreak and Groeteschele sets out to join a military conference, not even tired. Like a vampire, he needs no sleep as he spins out his somber philosophy.

Ilsa is seated in his convertible. She wants him to drive her. Somewhere. Anywhere. When they park, she confesses that she is turned on by his talk of nuclear destruction and wouldn’t mind pressing the button herself. Ilsa would be the perfect audience for Dr. Strangelove. She has certainly learned to stop worrying and to love The Bomb. Groeteschele frowns and almost snarls at her, and when she kisses him, he slaps her.

“You’re not my kind,” he snaps back. Not “type.” Groeteschele is a warrior, the Jewish warrior who theorizes how best to destroy the eternal foe of the moment. He is serious, while Ilsa is merely a fashionable nihilist. She’s not part of his species and would have no place in his world of convicts and file clerks.

Meanwhile, reality is secured and held in check by the military-industrial complex. General Bogan (Frank Overton) is in Omaha, Nebraska, commanding the strategic forces and conducting a Congressman and a military contractor on a tour of his headquarters, which is an underground complex dominated by a huge screen displaying radar patterns, aircraft, and the locations of American and Soviet nuclear assets. A minor alert is sounded when a UFO is detected in eastern Canada, but Bogan assures the visitors that it is normal. Bombers and fighters scramble to their positions, but when it turns out that the UFO is only an airliner that has lost its way, all goes back to normal. Fail-safe prevails, as always.

Everything is normal, that is, except for one bomber group out of Alaska that continues flying towards Soviet airspace. Bogan orders them to return, but there is no response, and he is unable to establish radio contact. If the bombers are recalled before they pass their designated fail-safe points, their crews will assume that a war has begun and ignore any further radio communications, since they might be a Soviet trick, and proceed to attack their targets in the Soviet Union with their nuclear payloads.

A concerned Bogan calls the President. The film switches to another underground bunker where the President (Henry Fonda) and Buck (Larry Hagman), his Russian interpreter, try to stop the inevitable Soviet retaliation that will ensue if and when Moscow, the bomber group’s target, is hit. Fonda is low-key and polite. He deals with Buck and his secretary with Lincolnesque folksiness, but just outside the room they are in sits the military officer holding the nuclear codes he will need to order a nuclear attack.

Fail-Safe concentrates on a masterful use of close-ups that utilize sharp black-and-white photography to intense, dramatic strength. It recalled to me Carl Theodor Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), where the trial of Joan is shown almost all in close-ups, bringing out the heroine’s emotional tension. Here, however, the tension is not that of religious fervor but of rational men in positions of power trying to avert a catastrophe that was never supposed to happen. The dramatic, theatrical use of these close-ups and the shadows and silences between characters seem more theatrical than cinematic. Fail-Safe could well be a stage play, but this only increases its intensity and tragic power.

The film’s intensity rises as Henry Fonda, in his bunker, tries to convince the Russian Premier not to order a counterattack when it becomes apparent that is inevitable that Moscow will be destroyed. Fonda makes it clear that at least one of the bombers will get through. The scene switches to SAC headquarters, where Fonda orders the airmen to cooperate with the Russians in shooting down the bombers. Two officers refuse to supply the information concerning the bombers’ weaknesses, forcing General Bogan to collar a reluctant sergeant (Dom De Louise) and force him to hand over the classified information. “Louder,” Bogan snarls. “They’ve got to know we’re on the level.”

When I frst saw this in 1965, it was creepy to watch treason being committed on screen. Many people were aghast and disgusted at the idea of our sharing classified information with the Russians. The Russians!

[2]

[2]You can buy Son of Trevor Lynch’s White Nationalist Guide to the Movies here [3]

Back at headquarters, everyone is tense except for Groeteschele. He coldly predicts that the Russians won’t counterattack and insists that a full first strike should be ordered involving America’s forces to totally destroy them. Everyone responds coldly to this, but Groeteschele believes this is an opportunity to destroy the enemy and thus have peace. He’s ruthless, invoking Russia’s savage nature and the need to destroy it. But a general protests: “We aren’t the Japanese. This isn’t Pearl Harbor.”

Groeteschele is defiant: “The Japanese were right to attack. We were their mortal enemy. The one mistake they made was not to finish us off.” He presses his argument: Those who can survive are the only ones who are worthy of surviving. Blackie counters Groeteschele’s arguments, but the academic becomes coldly emotional, as if an opened curtain is revealing his psyche: “How long would the Nazis have kept it up if every Jew they met came at them with a gun? But I learned from them. Oh, I learned from them.”

Blackie is clinical: “You learned too well, professor.”

Again, I note the Jewish obsession with Nazis (the Holocaust hadn’t entered the language yet in 1964; back then, it still just meant a large fire), and Groeteschele’s narrowed eyes indicate that he wants to settle old scores. But the military commanders have no intention of starting a war. This is a huge contrast to Dr. Strangelove, where the generals are shown as comical, Right-wing buffoons. Here, they retain their dignity. The film shows them humanely, both American and Russian, knowing that they have families who will be killed in a nuclear exchange.

One of the bombers isn’t stopped, despite a fierce Russian attack that fires a nuclear weapon intended to kill the crew with a radiation pulse. Finally, with radio contact reestablished, the pilot’s wife frantically pleads with him to return, but the airmen have been trained to disregard this as an enemy ploy. Yet, we see the pain in the pilot’s eyes.

In this claustrophobic film, the only indication of the bomb dropping is from the American ambassador in Moscow, who is ordered by Fonda to report the bomb’s impact. They hear a loud screech over the telephone, which they are informed means that the phone has been melted by the heat from the blast. It’s a chilling sound effect conveying cold horror.

In a last-ditch effort to prevent all-out war, Fonda orders a bomber, commanded by Black, to bomb New York City in retaliation, despite the fact that Fonda knows the First Lady is on a visit there. The Russian Premier, whose voice goes the range from impatience, to pride, to anger and disbelief, and finally, to a sad recognition: “This was nobody’s fault.”

The President is tense: “I don’t agree. We’re to blame, both of us. We let our machines get out of hand.”

As for the dead, what, the President asks, do we say to them? That accidents happen?

Blackie releases the bomb over the Empire State Building, saving America and killing his own family, and then immediately commits suicide. The movie ends with frozen images of New Yorkers seconds before they are wiped out. The last frame is of a black boy looking at a white boy; perhaps a comment that the great racial issues of 1964 were meaningless compared to nuclear destruction?

Before this, Groeteschele sits at his desk jotting down figures while the generals sit stunned. In the same cold tone he exhibited when discussing convicts and clerks and destroying Russia, he offers statistics on the casualties in New York, as well as the need to disregard the idea of mounting any sort kind of rescue for the survivors, as it would be pointless. Nevertheless, he says that teams should be sent there to retrieve vital financial records from the ruins. He stares at the generals as if ready to curse them: “Our economy depends on this.” He snaps his briefcase shut and coldly judges the blank-eyed men in uniforms. “And the Lord said, those without sin among you cast the first stone.” He then walks out, totally in command as much as he was in his first scene, like a wandering Jew of destruction.

Fail-Safe is a study of the contrast between the President and Groeteschele. While the President is trying to undo a terrible mistake, finally destroying New York City to keep Russia from retaliating, Groeteschele calculates and plays chess, being the philosopher-king of the nuclear era. He has the freedom to do that; the President doesn’t.

It was an interesting choice to cast Henry Fonda as the President. A lot of liberals always wanted him to run for office: a thoughtful movie star, as opposed to Reagan’s presumed thoughtlessness. In Gore Vidal’s movie The Best Man, Fonda played a thoughtful, perhaps too thoughtful candidate for President. On the TV series Maude, its super-liberal, mouthy lead character at one point goes off the deep end and fantasizes about running a Henry Fonda for President campaign. Fonda was the right choice for portraying dignity and compassion. This was a world where being a liberal was actually something to be proud of and not, as Michael Savage has put it, a sign of a mental disorder.

The humane script shows the Russian officers on the other end of the line as confused, angrily demanding vengeance since they know they will lose their families in the attack. One of them even dies from a heart attack when his strategy to save Moscow fails. This is unlike the current hysteria, where Putin is regularly bandied about as a madman and Russia an expansionistic ogre, especially by Victoria Nuland, the Lady Macbeth of America’s Ukraine policy who is Groeteschele’s true heiress.

Having grown up during the Cold War, I believe the current media and social drumbeat is actually worse than what we went through. It’s a mixture of depression and unease in which Fail-Safe’s moral is ignored, since many elements leading the West seem determined to start a war, even casually discussing the use of nuclear weapons. Much of this could be bluster, as Kipling described his own era’s armchair generals who were Killing Kruger with their mouths, but there are too many talking heads on TV anxious to egg on the need for stronger war — while fighting, many cynically argue, to the last Ukrainian. Some states, such as Poland, seem to be chomping at the bit to rush in and fight Russia; one Polish general even demanded that Poland claim Kaliningrad, which is held by Russia (which until 1945 was Koenigsberg, a thoroughly German city).

Scott Ritter, the former intelligence officer and weapons inspector who exploded the myth of Saddam Hussein’s weapons of mass destruction, said that behind the scenes in Washington, the military is trying to defuse the situation in Ukraine. He said people like Nuland have no real influence; she’s just window-dressing, much like how he says the grown-ups in finance are trying to stem the excesses of the current administration’s inflationary debacle. It’s a cynical comfort that many of these media war-hawks are well-paid to create a panic. It would be encouraging if there were in fact real-life Henry Fondas and Blackies in Washington and the Pentagon to oppose Groeteschele’s offspring, who drum for war over the airwaves and in too many think-tanks.

Fail-Safe is a remarkably relevant film today.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[4]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[4]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.