Extremities:

A Film from Long Ago that Anticipated Today’s Woke Hollywood

Posted By

Stephen Paul Foster

On

In

North American New Right

| Comments Disabled

Extremity = “the furthest point or limit of something.”

I watched the suspense-thriller movie, Extremities, for the first time in the late 1990s. It was one of those rare films that really grabbed me and remained stuck in my memory. Not being sure why that was, I recently watched it again to try to understand its impact. Having done so, the title now has a special significance for me.

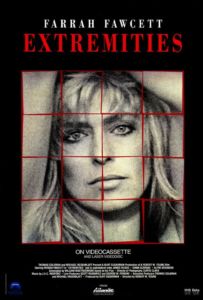

Extremities was released in 1986 and received mixed reviews. Siskel and Ebert named it one of the worst films of 1986 [2], yet Farrah Fawcett for her performance received a 1986 Golden Globe nomination for Best Actress in a film drama.

Upon seeing the movie again, I must say that in spite of its many shortcomings of implausibility it is worth watching for two reasons. First, the acting. Former “Charlie’s Angel [3]” (1970s-80s version) and pin-up-girl blonde [4] Texas-born Fawcett gives a mesmerizing performance as Marjorie, a woman fighting off Joe (James Russo), who attempts to rape her and plans to kill her when he is done. No cover girl make-up. No glamor shots. The rigors of the ordeal and the terror inflicted on her by Joe register on a red, blotchy face [5] smeared with tears, sweat, and snot. It is quite an anguished portrait of visceral fear and incredible horror. Russo’s performance is pants-pissing terrifying as the psychopath next door whose modus operandi apparently is to subject a carefully chosen victim to a sadistic ritual of conquest and demolition – prolonged sexual humiliations, forced degrading acts of submission, psychological torture – before moving on to the physical violations and termination. He takes his sweet time and clearly relishes experimenting with different ways to make his victims feel the crushing emotional effects of his suddenly usurped power over them. After forcing Marjorie to undress while he watches, she must tell him “I love you,” or else . . . You get the picture.

Second, is the sub-text of the movie. As mentioned above, I saw it the first time sometime in the 1990s when it became available outside the theaters. It was not, however, until my recent viewing that I was hard hit by the message conveyed by the casting and unfolding plot.

The movie opens with Marjorie finishing an evening racket ball game with a woman friend. It’s dark outside. On her way home alone after a short stop-off, she gets in her car and is seized from the back seat by a man in a ski-mask with a knife who clearly intends to rape her — and likely worse. She manages to escape from the car and her assailant, who chases after her. Her interview with the officious, mannish police lady is a bust. Since she has no description, there is nothing, she is told, the police can do. “Call us if he tries it again.” “Yeah, thanks for nothing.” Ominously, she lost her purse and wallet to the attacker. He knows where she lives.

The scene shifts to a few days later in the house Marjorie shares with two other women, Terry and Patty. It is early morning and Terry and Patty are getting ready to depart for work, leaving Marjorie alone for the day. Marjorie remains traumatized from the attempted abduction and mentions that she intends to buy a gun. Patty’s retort is in tone and substance that condescending, self-righteously expressed horror of guns that typically erupts from Lefty women when someone talks about getting one. “If you get a gun, one of us will have to move out.” Makes sense, don’t you think? Since the house appears to be out in the middle of nowhere, maybe the “virtue” of being unarmed will protect Marjorie against assault until the police arrive in time to draw the chalk outline around her dead body.

Terri and Patty depart. Marjorie is left alone and the movie grinds on for a bit with her “doing stuff” out in the yard that shows that she’s a physically vigorous woman and builds the tension-suspense of her vulnerability and anticipation of Joe’s entrance.

Joe suddenly appears, walking into her living room through an inexplicably unlocked front door. He then does his sadistic number on Marjorie, methodically working his way toward his ultimate goals: rape and murder. In their struggles, however, Marjorie is able to turn the tables, spraying his face with insect poison from a canister, thus blinding him. After a couple of blows to his head with a metal tea kettle, Joe is now the weaker, more vulnerable one in this dueling duo, and it’s time for a woman’s revenge: “I am woman, hear me roar [6].” Roaring in this case is Marjorie choking the bejesus out of Joe with a lamp cord, then hog-tying him and forcing him into the empty fireplace that she converts into a makeshift prison cell — a little Attica, perhaps. Upon “incarceration,” Joe now turns the tables on Marjorie, balefully asserting his victimhood, sowing doubts in her traumatized mind about whose account of this improbable imbroglio the police will believe when they arrive. She falls for it — the police won’t believe her — and thinks it’s best to kill him. I was sort of with her decision at this point.

Marjorie’s roommates return home from work in time to interrupt her frantic preparations to dispose of Joe. The film then lurches its way to an absurdist conclusion with a three-way cat-fight over what to do with a blinded rapist crumpled up in a fireplace whining about the hurt Marjorie had inflicted on him. “We are the World” Patty wants to attend to his injuries: “He’s a human being.” Marjorie wants to finish him off: “He’s an animal.” Terry, more of the timid sort, just resents Marjorie for dragging her into this mess: “I don’t want to go to jail.” Can’t blame her for that.

Marjorie eventually prevails. While torturing Joe with the hidden knife she discovers on him, she finally forces him to nix on his victimhood shtick and confess to a multiplicity of rape-murders, including his intention to kill all three of the women currently debating his future on an improvised death row. That finally gets the attention of Terry and Patty who, inexplicably, were having doubts about Marjorie’s version of her role in Joe’s current state of prisoner abuse. Now it’s okay to get the police. Patty and Terry leave to fetch them — Joe ripped out the phone — and the movie ends.

What impressed me most about this film was the casting and the extent to which a film’s dramatic credibility and plausibility could be sacrificed to the demands of feminist ideology, a factor completely and predictably missed by Gene Siskel in his panning of the movie’s faulty plot structure.

Let us, as they say, “Get real!” The “men are scum” insinuations jump out at you. First, all of the apparently professional women (late thirtyish) appear to be childless, with no serious connections to men or any need for them. Remember: “A women without a man is like a fish without a bicycle.”

[7]

[7]You can purchase Trevor Lynch’s Classics of Right-Wing Cinema here [8].

But the most egregious is the profile of Joe, the principal male character. In a brief, cutaway scene before he appears at Marjorie’s house, we see Joe at his home, going through Marjorie’s stolen wallet in preparation for “a visit.” He is sitting at what appears to be his workbench in his garage, with the camera behind him. All we see of him from this angle are his forearms and hands, which show the marks of manual labor as well as a wedding ring. On his worktable are some of the tools he uses to make his living. You guessed it: He’s a blue-collar guy, and as we will shortly see, he is relatively young and white. The scene ends with his young daughter (seven or eight) peering through the window on behalf of her mother and calling him for dinner. “I’ll be there shortly, sweetheart,” he responds.

Joe is a working class, family man. He has a regular job. His wife fixes his dinner; his daughter sweetly summons him. They obviously care about him, and they are in his charge. He probably goes to church. Joe’s secret hobby is raping and killing women strangers he happens to take a fancy to, however.

I can’t help but wonder if the screenwriter was channeling Theodor Adorno and his Authoritarian Personality. Behind the wholesome-appearing, traditional American family man you will find a repressed, sexually-depraved monster waiting to break out and express himself by hurting innocent people. Change the setting a bit and Joe could be a Klansman lynching a negro boy in Mississippi, a guy sex-trafficking underage girls from Canada into Detroit, or a raging hater of homosexuals, prowling around the guy bars while looking for the right queen to torture and kill.

When we get the first full glimpse of Joe as he appears in Marjorie’s living room, it’s confirmed: He’s a blue-collar guy: jeans and a workman’s vest over a short-sleeve white tee-shirt revealing the tanned, well-muscled arms of a man who regularly uses them for something more strenuous than pushing papers. He’s not big, but fit and ruggedly good-looking, with a decent haircut. In his late thirties, with his looks, he could easily attract nice-looking women. But all that “normality” is just a façade; he’s a nasty piece of work who is about to pounce on his latest prey.

Upon his intrusion, Marjorie attempts a series of futile rebuffs to drive him off. The last one is a ruse, and it is especially worth noting that Joe knows it is bullshit.

“My husband is sleeping upstairs.”

Joe smirks and waits.

“He’s a cop.”

Pause, then desperately: “Honey!”

Joe steps in mockingly to assist Marjorie and turns toward the stairs. At the top of his voice: “Honey!”

Joe turns and grins at Marjorie. He is now fully in charge and discharges a piece of sarcasm that speaks to the movie’s central motif: Men! What are they good for?

“Now ain’t that just like a cop; never there when you need him.”

We now have a solid grasp of the entire composition of Marjorie’s world of men: an imaginary man of her invention who is utterly useless for protecting her, and a real one about to rape her. There are no good-man options to speak of.

The world of men as this film moves forward continues to be filled with disappointment. Joe comes in two flavors: with the upper hand, he is the murderous psychopath, depraved and with the pathological baggage of arrested development — sexually speaking. Defanged and chained like a dog, the macho-man turns into a helpless little boy: “The expropriators are expropriated.” [9] Joe is hurt. He’s needy. Marjorie had better do something about it or else she’s going to be in trouble with Dad — the cops. In the best tradition of professional victimhood, he does his best to guilt-leverage his now disadvantaged position with grievance-mongering and threats.

The film’s feminism reaches the “full monty” when the three women quarrel about what to do with this lying bundle of human rubbish, now completely at their mercy. Of course, it gets very emotional with Terry and Patty half-buying Joe’s line that his impromptu “incarceration” is the result of a one-night stand gone bad. Men, we all know, are good at turning women against each other. Marjorie’s threat to castrate Joe with his knife pushed firmly against his crotch achieves the desired result, however, and he is reduced to a state of helplessly blubbering out the shocking details of his secret hobby. We’ve now seen the full range of manhood from threatening and lethal to helplessly, hopelessly, cry-baby infantile, with nothing in between that’s not ugly.

Terry throughout is a useless wreck, and near the end we find out why — and, as you might suspect, her confession does not reflect well on her. I’m sorry, men. She reveals that as a teenager she was raped by the father of a girlfriend, and that she simply had to, so to speak, grin and bear it. Because? Well, once again, we need Professor Adorno to explain it. Her rapist was a family man with a daughter of his own. Having a daughter of his own, you might think . . . But, no. He was a patriarch in a patriarchal society and simply taking advantage of the perks. Just to be clear, it was Terry’s girlfriend’s father who raped her, mind you, not the girlfriend’s brother. Rapist Joe, a father; Terry’s rapist, a father — rape is just what fathers in a man-dominated world are inclined to do. In case you have still not gotten the message from the film: Men are scum.

Patty, who happens to be black and a social worker, is in contrast to the utterly discomposed, pale-faced Terry, a take-charge personality with a social conscience. She responds to Joe’s cry for assistance, extracts him from his cage, and gives him food and water. Also, she dispatches Terry to the pharmacy to bring back an antidote for the insect spray that Marjorie dosed him with. Terry is instructed to make haste with her mission and return before Marjorie goes ahead and offs Joe. Patty operates with a humanitarian, color-blind view of the world in contrast to the white girl who is obsessed with revenge and is hell-bent on murdering someone. Patty’s vignette in the last scene of the film is a racial, invidious comparison trope that is now ubiquitous in contemporary film entertainment.

Extremities was released 36 years ago. It is a single, powerful instance that illustrates what has become the central feature of the contemporary entertainment industry — it function as a propaganda instrument for the insidious ideologies of feminism, social justice, and anti-racism. It is nearly impossible to exaggerate the pervasiveness and now blatantness of the propaganda that saturates every aspect of American entertainment, which explains the success of the Cult-Marx march through our institutions and explains why the extremities of 2022 extend far beyond those of 1986. From “Men are the enemy” to “Men who want to be girls are girls” and “courageous” for asserting themselves; from “racial discrimination is bad” to the “extinction of whiteness.”

Entertainment, which once, perhaps, was used as an escape from reality, has become the complete replacement of reality. Netflix, Amazon Prime, ESPN, and so on are the chains in Plato’s Cave of the twenty-first century, binding the viewers to the flickering shadows on the wall they mistake for reality.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[10]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[10]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.