Dimitri Has Left Us: A Look Back at Guy Mouminoux’s Journey

Posted By Kristol Sehec On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled2,512 words

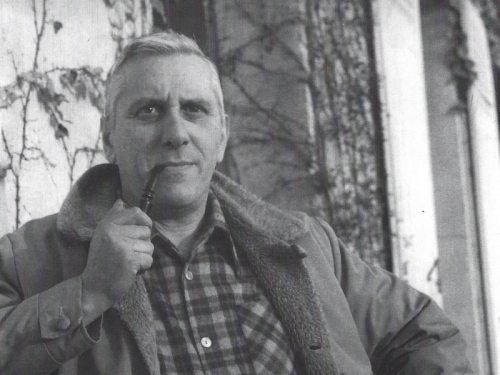

Guy Mouminoux, who died on January 11, 2022, is remembered for his only novel, the autobiographical war story The Forgotten Soldier (under the pseudonym of Guy Sajer) as well as for his humorous or historical comic strips (under the pseudonym of Dimitri).

Mouminoux was born in Paris on January 13, 1927. In 1916 his father, an infantryman who had been taken prisoner in Verdun, met his mother during his detention in Germany. Guy spent his youth in Alsace and was passionate about reading children’s comic books. He had a gift for drawing and dreamed of making it his profession. But in 1940, when this region was annexed by Germany, he joined the German youth camps. In 1943 he enlisted in the Grossdeutschland division of the Wehrmacht and participated, at only 16 years old, in the fighting on the Eastern Front.

Children’s Comics

In the first part of his career, without having studied at art school, Guy Mouminoux devoted himself to comics for children, which had been one of his youthful passions. At the end of 1946 he published The Adventures of Mr. Minus, his first comic strip. It was the beginning of a long involvement with illustrated books for young people, of either a Catholic persuasion (Cœurs vaillants, etc.) or a Communist one (Vaillant). It should be remembered that in October 1945, when Cœurs vaillants was temporarily banned from publication to determine whether it had “collaborated,” the Communists launched their own newspaper for young people, Vaillant, playing on the similarity of the titles. From 1959 he resumed the series Blason d’argent in Cœurs vaillants, recounting the adventures of Amaury, a brave knight fighting injustice. He then made a name for himself in the world of comics.

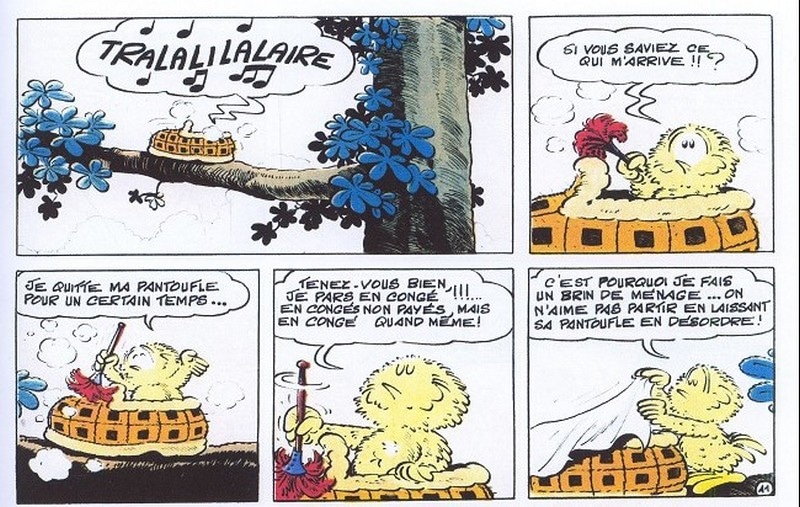

Mouminoux also published short historical stories for children in the Spirou newspaper, entitled Belles Histoires de l’oncle Paul. At Spirou he met Jijé, a major author of Christian comic strips who became one of his best friends. In the mid-1960s, they produced a few volumes of the series Les Aventures de Jean Valhardi together. In 1964 he created a humorous series, Goutatou et Dorauchaux, for the magazine Pilote, imagining a tugboat that has two cats for its crew. He then developed his characteristic style for the series Le Goulag. From 1970 to 1980 he drew the humorous series Rififi for Tintin, about a young sparrow who is chased from the nest by his brothers because of the punishments they inflict on him.

The Forgotten Soldier

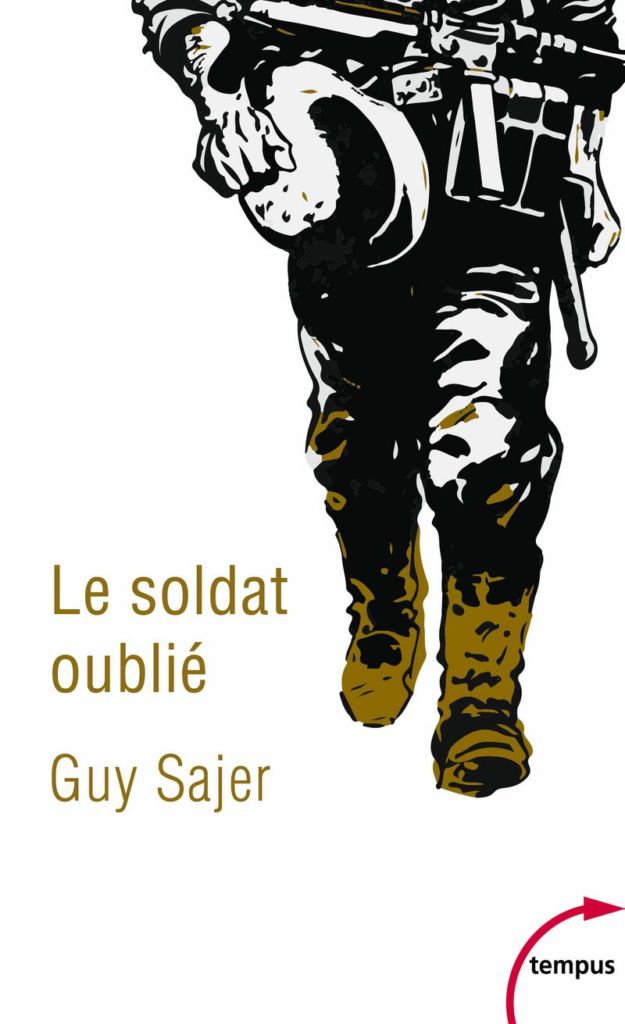

In 1967 Mouminoux published The Forgotten Soldier with Robert Laffont, which won the Prix des Deux Magots in 1968. Translated into nearly 40 languages and selling nearly three million copies, this autobiographical account describes his participation in combat with the German army. In it, we learn that Guy ended up in the service of the German Reich within the framework of the Arbeitsdienst (Reich Labor Service). He began as a supply specialist for the troops on the Eastern Front. During the winter of 1942, the cold was intense. His unit was unable to join Field Marshal Paulus’ 6th Army at Stalingrad, and retreated from Kharkov to Kiev. At the beginning of 1943, after taking leave in Berlin, where he met Paula, he volunteered to join the Grossdeutschland division. He then participated in the Battle of Kursk before retreating to the Dnieper. While attempting to repel the Soviet advance he fought alongside the children and old men of the Volkssturm. In April 1945, he surrendered to the Anglo-Americans. Initially a prisoner of war, he was quickly released because of his French origin.

In his account, he reveals the strong camaraderie within the German army, and describes in detail the German soldier’s living conditions. We learn about the terrible Russian winter (−40°C), which caused frostbite and amputations. But although Mouminoux took care to publish this novel under a pseudonym, Guy Sajer (after his mother’s maiden name), the world of comics discovered the true identity of this author who remained fascinated by the courage of these soldiers who were ready to give their lives for a cause. Consequently, Guy Mouminoux was occasionally rejected by some publishing houses.

The Gulag

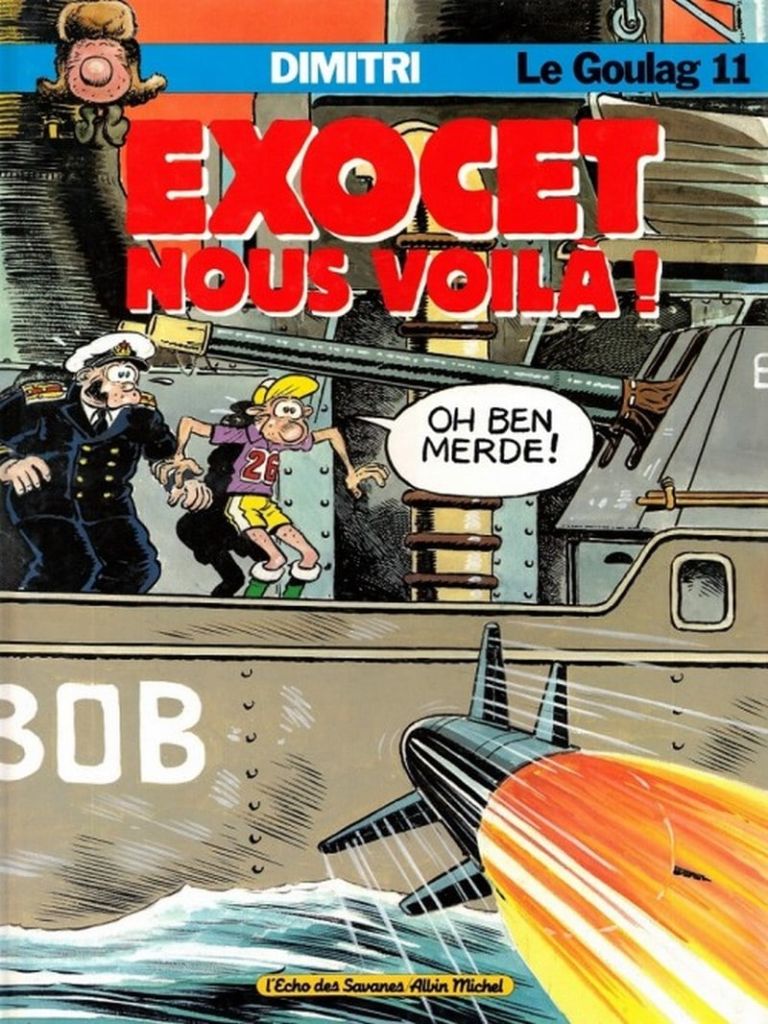

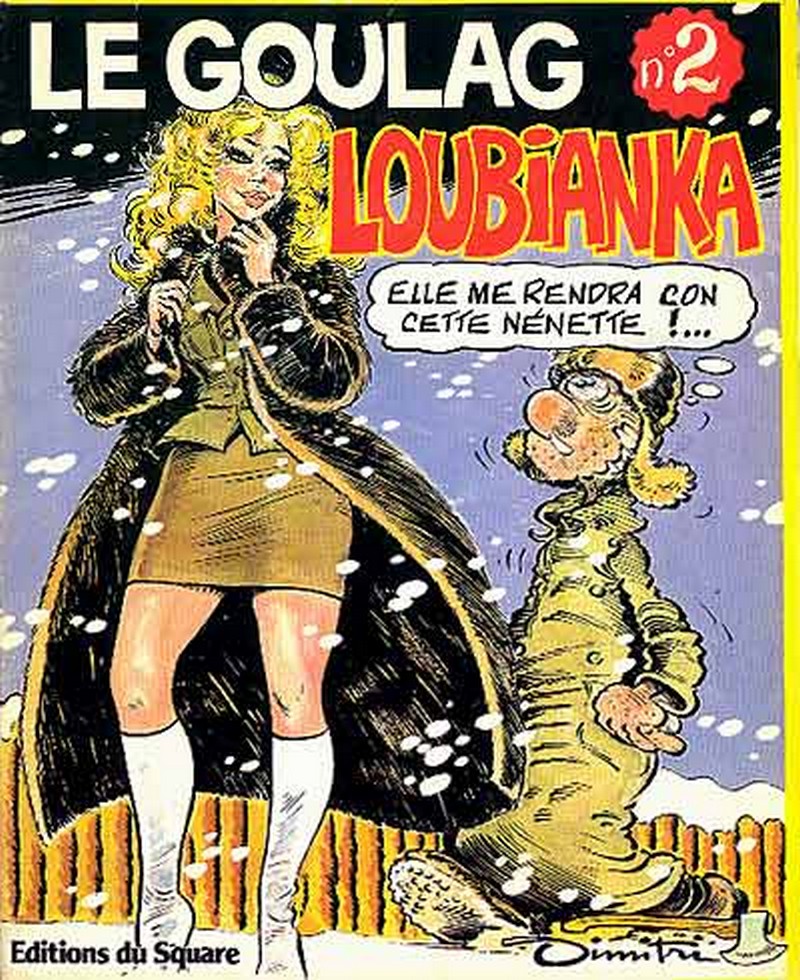

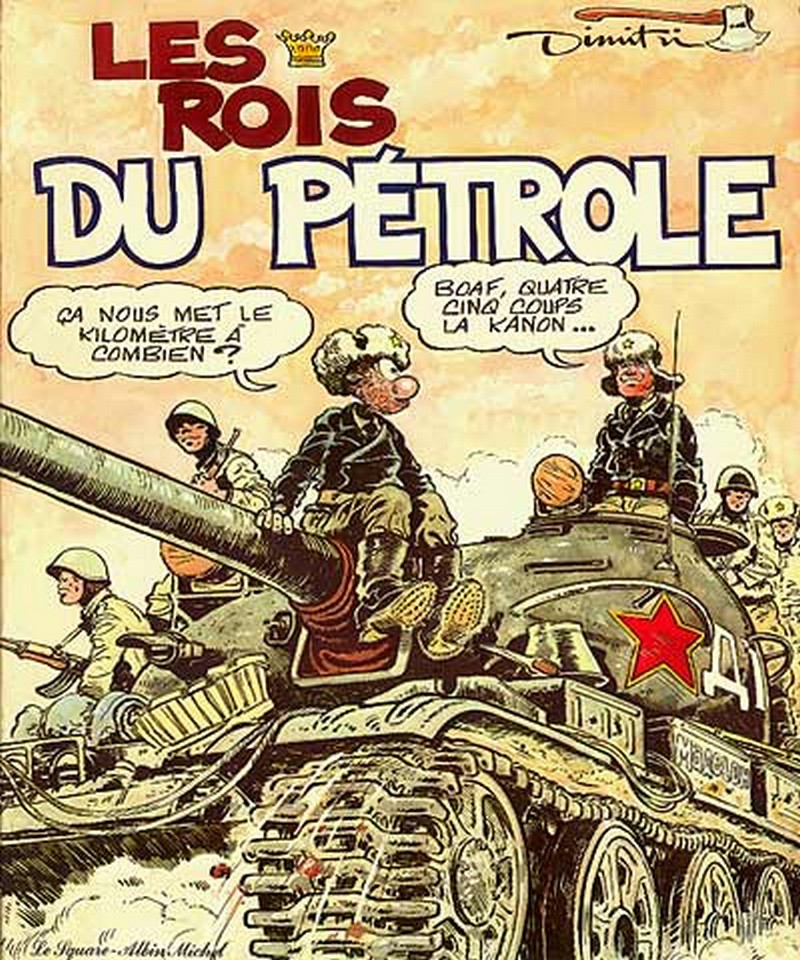

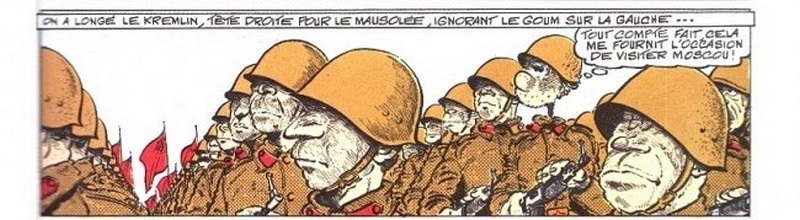

In 1975 Mouminoux took the pseudonym of Dimitri. He then drew his best-known series, Le goulag, which appeared in the magazines Hop!, fanzine, Charlie mensuel, L’Hebdo de la BD, L’Écho des savanes, L’Événement du jeudi, and Magazine hebdo. There he met Wolinski, Cavanna, Cabu, Gébé, Choron . . . and Reiser, who became one of his best friends. The Gulag’s main character, Eugène Krampon, is a phlegmatic Parisian worker who emigrates to the Soviet Union and is then interned in Gulag 333 in Siberia following a misunderstanding. There he has some surprising adventures, becoming a test pilot, a soldier on the Sino-Russian border, a football champion . . .

He discovers that with the fall of the Soviet empire, Russia is opening up to capitalism. Burgers end up replacing good Russian cuisine! But he can think only of finding his beautiful Lubyanka. By addressing a more adult audience, Dimitri gained greater recognition. He explained that “the Gulag, for me, is life. It surrounds us, we are right in it. We can cry, but also laugh. It’s a bit like war” (Le Choc du Mois, November 1990, p. 54). Even if Dimitri humorously denounces the Communist regime, he nevertheless remains very attached to the Russian people.

After René Goscinny’s death in 1977, Mouminoux was approached by Georges Dargaud, who was then in conflict with Albert Uderzo, to continue the Asterix the Gaul series.

During this period, the Left suspected him of being far Right while the Right accused him of being friendly with the Left.

The Period of Scathing Humor

Dimitri drew many satirical comic strips in the early 1980s.

Deo Gratias (1983), which was composed of short stories featuring grating black humor, revealed Dimitri’s desperate view of modern civilization. His criticism of feminism, as in a woman demanding to fight a man in a boxing match, is particularly fierce. Black-and-white suited him very well.

In The Dog Leader (1984), a man who hates modern civilization is about to commit suicide but then discovers that he has the power to talk to dogs. He ends up leading a pack of ferocious dogs to attack defenseless humans. He orders them to kill and eat them. In this merciless story, the attacks are so bloody that it is almost a horror comic.

Les Mange-merde (1985) describes a society plagued by insecurity and unemployment. A revolution breaks out. A young entrepreneur is ruined. He crosses paths with a young inventor. Together they enter a bistro, described as “the last Gallic refuge.” They must run away from a gang of racketeers. Again, Dimitri uses his fierce dark humor to reveal the state of society.

Pognon’s Story (1986) is an astonishing sociopolitical satire tinged with biting humor. Let us judge: A man, on vacation by the sea, tries to earn money by deforming his body to take on the appearance of animals. Then he joins the crew of a boat leaving for Central America. There he meets a nymphomaniac adventurer who is trying to fraudulently buy military vehicles in Honduras. Then a hermit reveals to him the secret of a magic stone that restores lucidity to those who cling to their testicles! But this power worries the government . . .

Contrary to what its title might suggest, the comic strip Les Consommateurs (1987), with its caustic humor, is not a critique of consumer society. A fake doctor finds himself without an office. He agrees to attend to the bedside of an international crook protected by the secret services. After having his butt bitten by a bewitched barracuda, he turns into a salamander and can only live in a bathtub.

In La Grand’messe (1988), a garbage collector wants to change jobs. After a car accident, he becomes the double of a minister and replaces him in order to make meaningless political speeches. Here, Dimitri criticizes politicians who look down on their constituents, whether Left, Right, or center.

The Slaughterhouse (1989) earned him his firing from Dargaud. Dimitri imagined that a man at the end of his rope joins the police. This is an opportunity for him to denounce the lynching of an unarmed police officer and the fact that the judiciary ends up ignoring it. He affirms that “one would like to create disorder and chaos that one would not otherwise carry out” (Le Choc du Mois, Nov. 1990, p. 54).

Historical Accounts

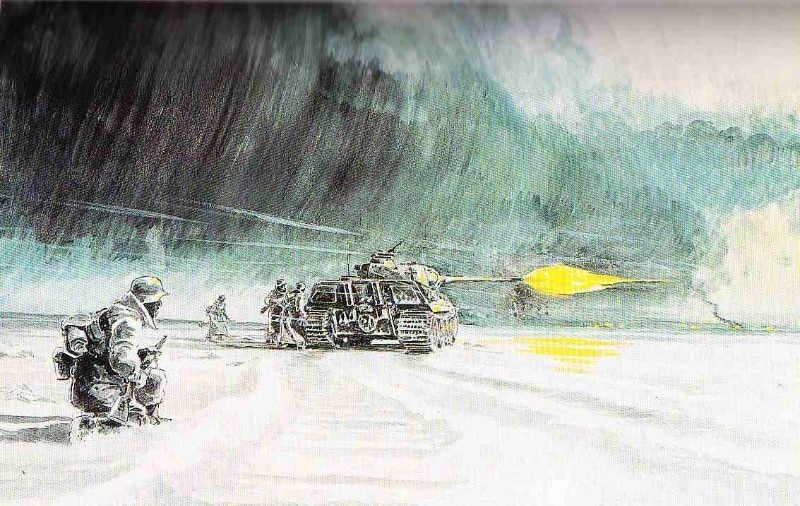

From the 1980s Dimitri was involved in the great success of historical comics, drawing particularly poignant stories. It is extreme conditions that inspired him. For each of these strips, Dimitri took himself very seriously. He hired models in order to draw them from all angles.

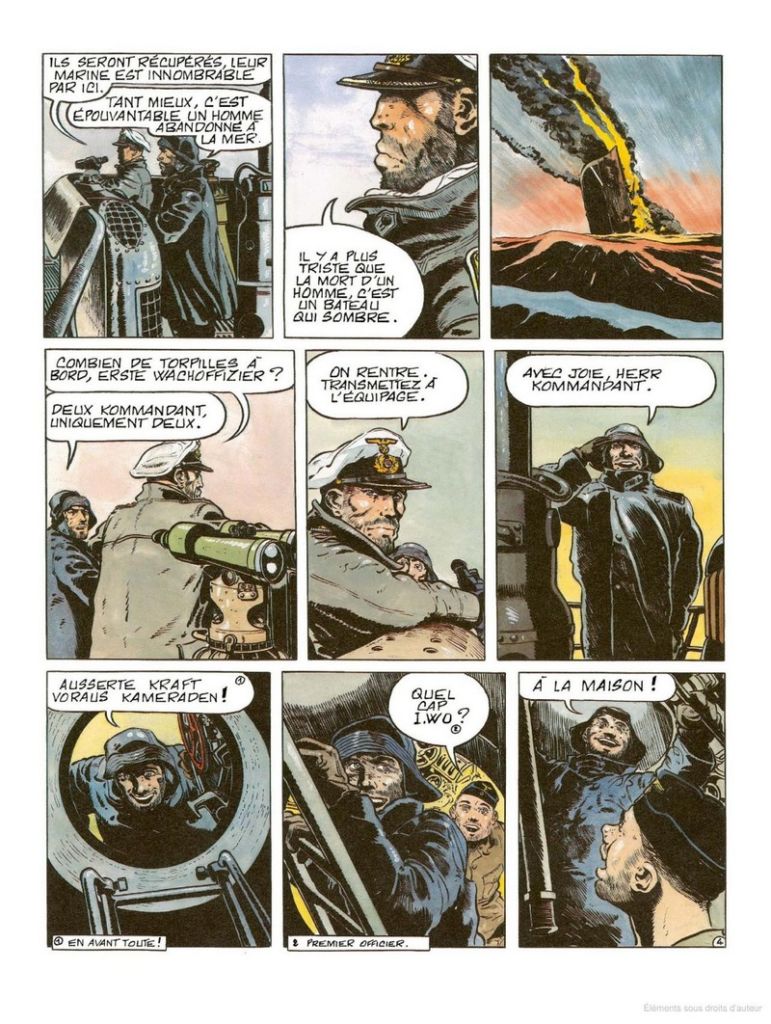

The Second World War remained his favorite theme. His masterpiece is undoubtedly Kaleunt (1988). It tells the story of Heinrich Schonder, Captain of Unterseeboot 200, who shows little interest in the National Socialist regime. We learn about the terrifying lives of submariners until it is sunk on June 24, 1943. The expressive drawing and coloring are superb.

In the following year, in Raspoutitsa (1989), Dimitri describes the captivity of a German soldier after the battle of Stalingrad. He perfectly illustrates his despair as he walks in the snow in columns of prisoners who are being sent to the Siberian camps.

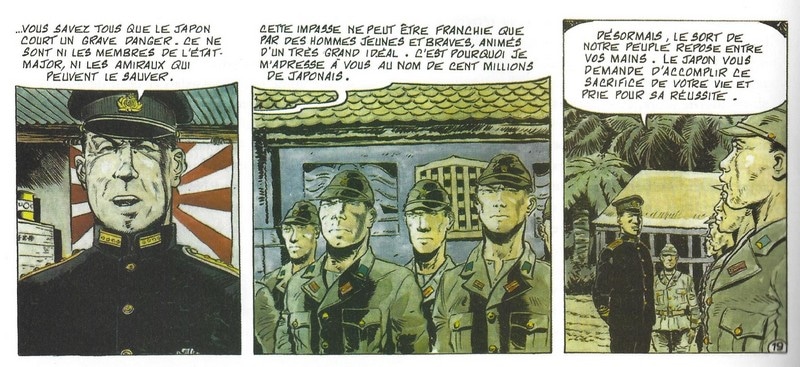

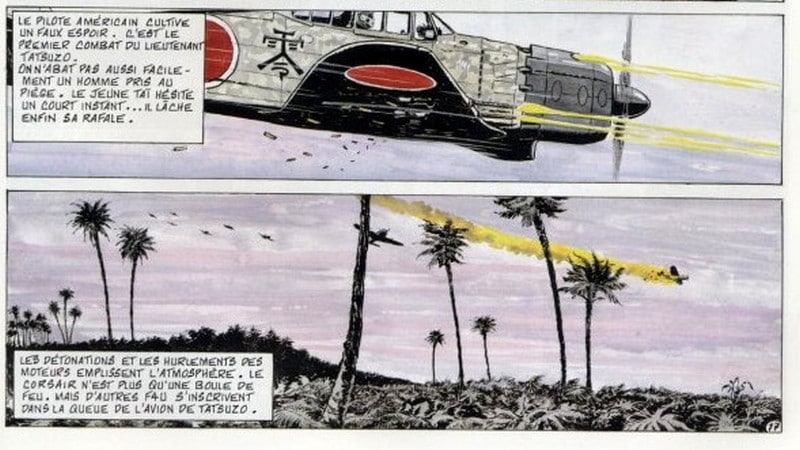

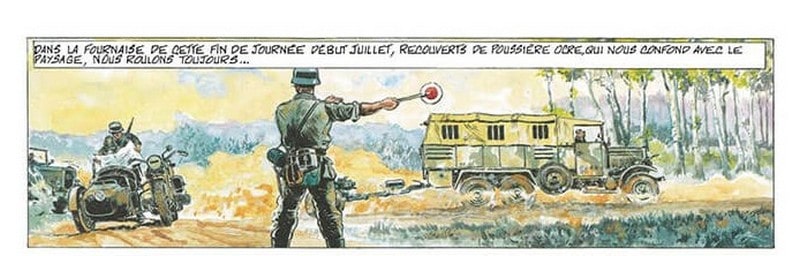

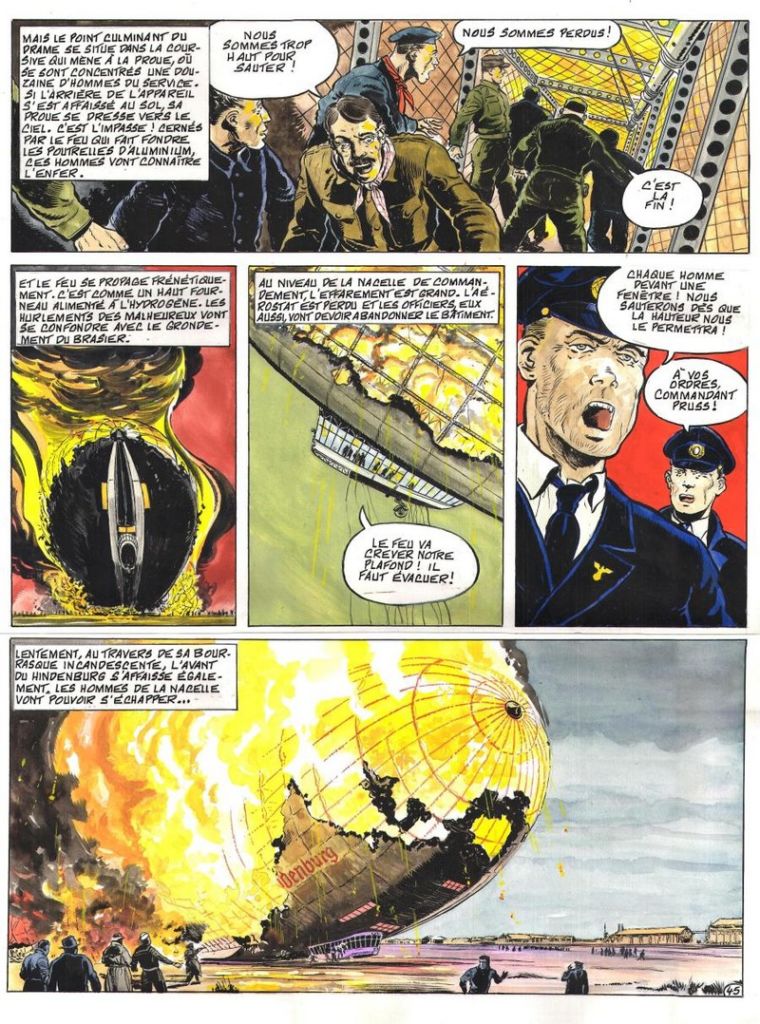

Other comics are set during the Second World War as well. In D-LZ129 Hindenburg (1999), Dimitri considers the hypothesis that a conspiracy was behind the burning of the zeppelin Hindenburg on May 6, 1937. [15]In Kursk tormente d’acier (2000), Dimitri describes in great detail the journey of a German army soldier engaged in the Battle of Kursk who witnesses the atrocity of war. Kamikazes (1997) describes the psychology of a young Japanese airman sacrificing his life for his country. Dimitri shows that his sense of honor is the same as that of the samurai.

[15]In Kursk tormente d’acier (2000), Dimitri describes in great detail the journey of a German army soldier engaged in the Battle of Kursk who witnesses the atrocity of war. Kamikazes (1997) describes the psychology of a young Japanese airman sacrificing his life for his country. Dimitri shows that his sense of honor is the same as that of the samurai.

In the second volume of Under Fire! (2011), Dimitri advocates the sense of honor of a young Japanese officer descended from a family of samurai. During the Battle of Malaya (December 1941), he fights bravely and respects his prisoners. But, sanctioned by a superior officer, he must now watch over English prisoners who are responsible for building a bridge. Despite the bridge being sabotaged, he continues to defend the English prisoners of war. This chivalrous spirit towards the enemy saves him from internment in 1945. In all these war stories, Dimitri explores the warrior’s tormented conscience, but he also endorses the Allies’ point of view. The Convoy (2001) thus reveals the anguish of American sailors delivering weapons to the Russian army, always under threat from German bombers and submarines.

One exceptional work of his from 2008 was the screenplay for the first volume of the series The Forgotten Empire. It tells the story of Üdo Sajer, a young 16-year-old from Württemberg. In 1805, fascinated by the Napoleonic army, he manages to enlist, leaves the Holy Roman Empire, and receives military training. But from his first battle, the young Sajer discovers the horror of war. . . Dimitri thus seems to have fun imagining his career if he had been born two centuries earlier, serving in the Napoleonic army instead of the Wehrmacht.

Fascination for the Forest & the Sea

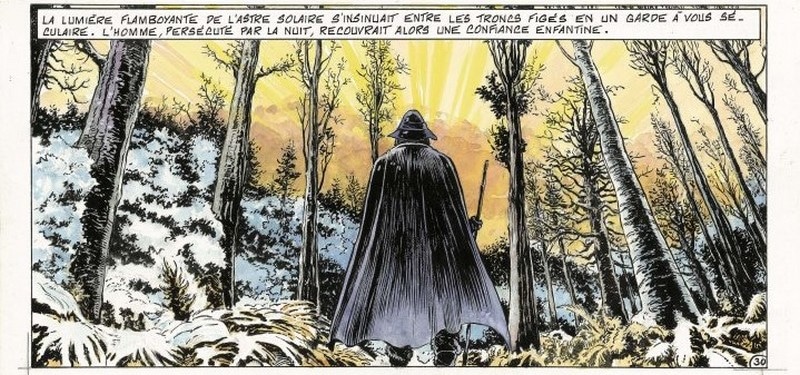

Whenever he had a free moment, Dimitri would go for a walk in the forest. He took refuge there when he was upset or depressed. He celebrated his love of the forest in the comic book Ode to the Forest (1994). At the end of the first millennium, a wandering knight flees and goes deep into the forest of Saxony. He possesses a black stone that gives him strange powers. After many adventures, he metamorphoses into a beautiful solar warrior in magic armor. Released in 2007, La Malvoisine was inspired by Reynard the Fox. Dimitri imagines the misadventures of a wise old man who tries to bring order and justice between humans and animals, and has to deal his warrior neighbor who believes that man must dominate the animal world. For this story, he took up the animal drawings of his youth again — but these two medieval legends are nevertheless disappointing.

Since he was also fascinated by the sea, Dimitri was a regular at Brest’s international maritime festivals. In many of his stories he shows the harshness of life on the open sea.

Meurtrier (1998) evokes the dramatic life of a poor orphan who, after losing his parents at the age of five, is taken in by a sinister institution, sentenced to prison for murder, and then becomes an infantryman during the First World War. This strip allowed Dimitri to draw terrifying maritime storms.

In Haute Mer (1993), Dimitri describes the journey of a whaler who ventures into Arctic waters on the eve of the First World War. Ready to face all dangers, the commander searches the sea for a mythical creature. Dimitri’s realistic drawing is so perfect that it feels like you yourself are sailing across the high seas.

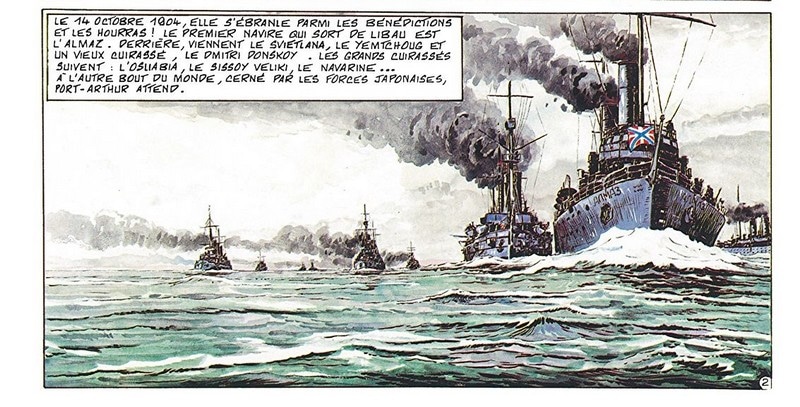

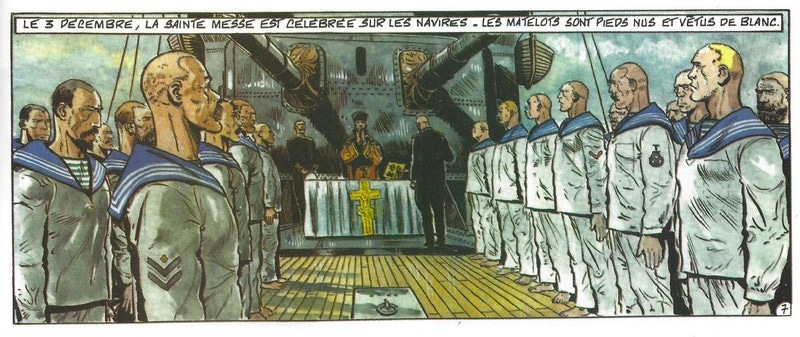

In Under the Tsar’s flag (1995), Dimitri depicts the naval battle at Tsushima, when the Russian forces of Tsar Nicolas II were defeated by the Japanese on May 27 and 28, 1905. We discover the daily lives of the Russian fleet’s sailors as well as the horrors of a modern naval battle.

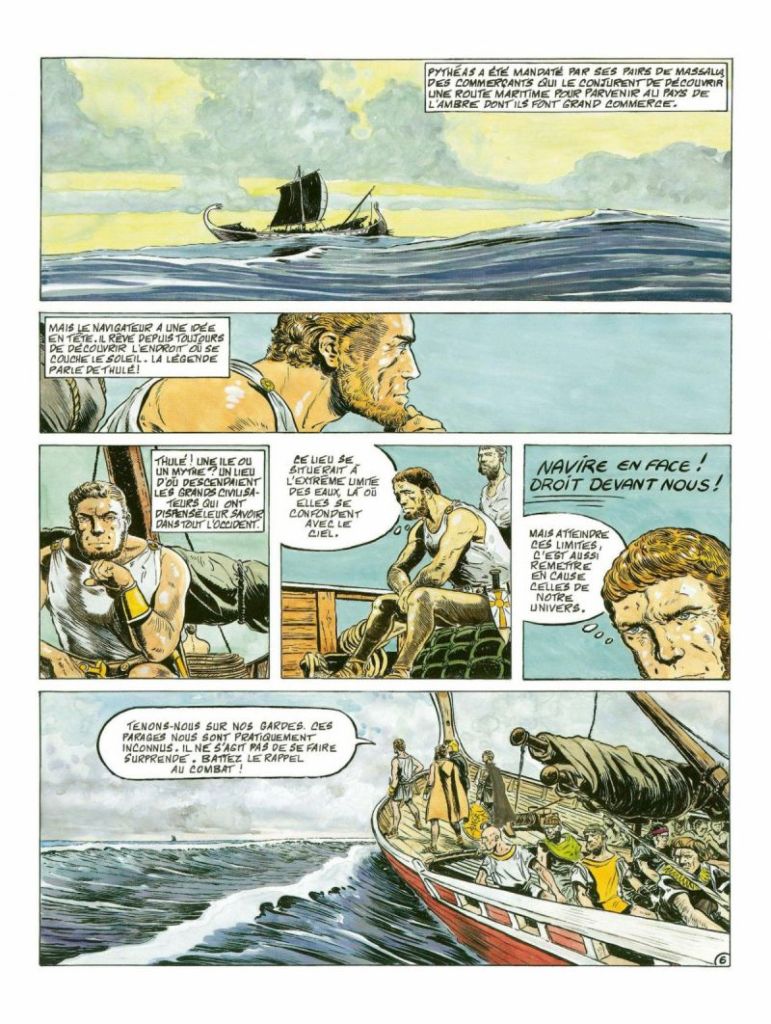

Dimitri’s most surprising story is undoubtedly Le Voyage (2003), published by Albin Michel in 2003. Around 330 BC, the scholar Pytheas, a native of the Greek colony of Massalia (Marseille), sets sail to explore Nordic Europe. He passes the Pillars of Hercules (the Strait of Gibraltar) and discovers the phenomenon of the tides, which was then unknown to the Greeks. Managing to avoid Moorish pirates, he pushes further north and reaches Armorica and its megaliths. After seeing the country of the Picts, he arrives at the island of Thule, located in the Arctic Circle. Giving way to his imagination, Dimitri does not hesitate to recount an encounter between Pytheas and the ancient gods and then the Atlantean people. Reading this comic again after Dimitri’s death remains a moving experience.

[22]Dimitri defined himself as a European, never feeling out of place anywhere in Europe (Le Choc du Mois, Feb. 1989, p. 68). He seemed very calm, with polite manners, but his life remained marked by his experience as a combatant during the Second World War. He put it this way:

[22]Dimitri defined himself as a European, never feeling out of place anywhere in Europe (Le Choc du Mois, Feb. 1989, p. 68). He seemed very calm, with polite manners, but his life remained marked by his experience as a combatant during the Second World War. He put it this way:

I still jump out of bed at night. The thirty months that I spent in the army represent for me 75% of my vital experience. The rest of my existence seems to me so pleasant, so easy in comparison . . . And it is perhaps monstrous to say, but this atrocious period of my life constitutes, at the same time, all my wealth. Whatever I do, whatever I seek as a source of inspiration, I invariably come across it. (Vécu, June 2000, p. 85).

On an artistic level, Dimitri had learned his craft on the job. He was the complete author of his works, producing the scenario as well as the drawings. This is perhaps the reason why his full style of drawing, which has a rich, racy, and virile brush stroke, was so characteristic. He drew with his guts. In his comics, one always encounters the dramatic idea that we do not escape our destiny, even though this idea was often rendered with humor.

This essay is a translation of one that appeared at the French-language site Breizh-info [24] and is published with their permission.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[25]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[25]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.