What Concerned Us Separated Us: How the Abkhazis Fought Their Own Great Replacement

Posted By Morris van de Camp On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled [1]

[1]Rita Zongurova [2] from Tkuarchal served as a medic during the conflict.

2,100 words

If you read the mainstream media, it’s all over for white America. The forces of the Great Replacement are unstoppable. Our cities are forever destined to be “revitalized” by refugees. COVID-positive illegal immigrants will be flown from the border to the interior by the Biden regime in midnight flights via Crooked Hillary’s Central Soviet of Multiculturalism. Cultural objects that have been destroyed will not be remade. Books by dead white males will be thrown into bonfires while Obama-sons dance around it, wielding their assegais. [3] Martin Luther King’s dream will haunt our sleep forever.

The story of the Abkhaz people [4] can give American whites some hope and advice, however. Abkhazia is a tiny, mountainous region along the Black Sea’s eastern shore. The Abkhaz people are mostly Eastern Orthodox while their upper class is often Sunni Muslim due to Ottoman Turkish influence, but their ancient faith [5]’s traditions continue to be observed. In fact, that ancient faith has had a revival since their war for independence. Many believe their god Dydrypsh [6] awarded them victory, and their traditional bull sacrifices have resumed, although the Abkhazis subordinate their religious convictions to the good of their people.

The Abkhaz [8] language [9] is part of the Northwest Caucasian language family [10]. Northwest Caucasian is a language family of its own. Among the nations of the Caucasus Mountains, their languages are vastly different: Turkic languages [11] are spoken in Azerbaijan, Armenian [12] is Indo-European, and the Georgian language is part of the Kartvelian language family [13]. One can go down a rabbit hole of speculation regarding these language families and their relationship to Basque [14], Dené [15], or Etruscan [16].

The Abkhaz people have long been ruled by others: the Greeks, the Romans, and the Ottomans. But things got really tough for them after 1810. That was when the Russians conquered the Caucasus from the Ottoman Turks. They dealt with the ferocious attacks of Circassian tribes [17], some of which were Abkhaz, by deporting the Circassians to the Balkans, Anatolia, and the Middle East — where they founded Amman, Jordan (among other places) [18].

Abkhazia was thus depopulated. When the Communists arrived, everything got worse. The Abkhazis became inmates in the prison of nations that was the Soviet Union, and they were seen as the lowest of the low. In 1922, Abkhazia was a separate Soviet Socialist Republic (SSR), but in the 1930s, they were folded into the Georgian SSR.

This change in status in the 1930s was significant. It meant that that the Georgians could move their impoverished and landless population into Abkhazia. This transfer initially caused few problems. The Abkhaz offered the displaced Georgians food, and they were helpful. The two communities intermarried and attended each other’s feasts, funerals, and weddings, but then things slowly started to break down.

Anastasia Shesterinina [19] quotes one Abkhazi’s remarks about this time:

In 1939, they started resettling Georgians. Where there were few Abkhaz, Georgians were given land and small houses. The village that you passed when you came to meet me, there were very few Abkhaz there, and so it became a Georgian settlement. [Then-Soviet leaders Lavrenty] Beria and Stalin [who were both Georgian] relocated them to destroy the Abkhaz, so that there would be no Abkhaz nation.[1] [20]

[21]

[21]You can buy Greg Johnson’s The White Nationalist Manifesto here [22]

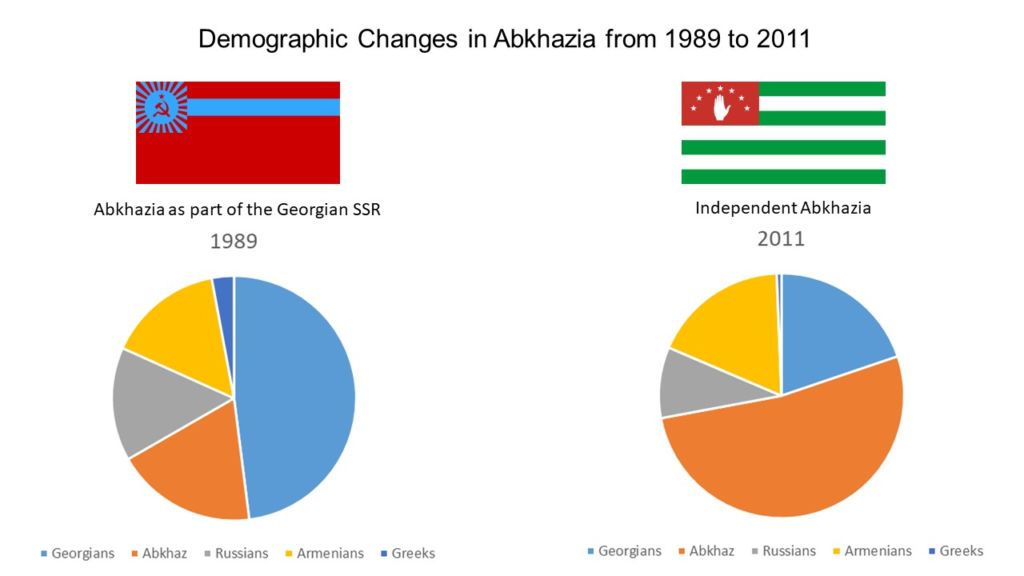

The Georgians were demographically swamping the Abkhazis. As they did so, the noose tightened around Abkhaz culture [23]. In the late 1920s, shortly after Josef Stalin became the undisputed head of the Soviet Union, Soviet bureaucrats began to count Abkhazis as Georgian. Then, names of geographical locations and cities were changed or Georgianized. In the mid-1930s, the Abkhaz language’s alphabet was replaced by the Georgian alphabet. In 1946, Abkhaz language schools were closed, as were Abkhazi printing presses. The Abkhazi Writers’ Union was renamed and Abkhaz cultural events were suppressed. By 1989, the Abkhaz were just under 18% of the population.

In 1954, a Soviet academic who “happened to be Georgian” named Pavle Ingorokva [24]published a theory that the Abkhaz were not native to the region and had instead migrated there from other parts of the mountains. Abkhazia became a land without a people for a people without a land.

The Soviet Union was at the height of its repressive powers at the time. Soviet troops occupied all of Eastern Europe, and Soviet cosmonauts and rocket scientists dominated space. The Soviet Air Force exploded the largest bomb ever devised in the Arctic [25] as a demonstration of their technological power. A good portion of the global intelligentsia were certain that the Soviet Union represented the future and that their system would gradually expand to encompass the globe.

The few Abkhazi ethnonationalist activists there were in the 1960s were imprisoned by the Soviets, often for a decade or more. Soviet political dissidents were nearly always ethnonationalists, not libertarians seeking tax cuts for corporations. Trouble was brewing in the schools, though. The classes were taught in the Georgian language, and the teachers were barely educated themselves. Any Abkhazi appeals to the Kremlin were routed through the Georgian SSR’s government in Tbilisi, where they went no further.

[26]

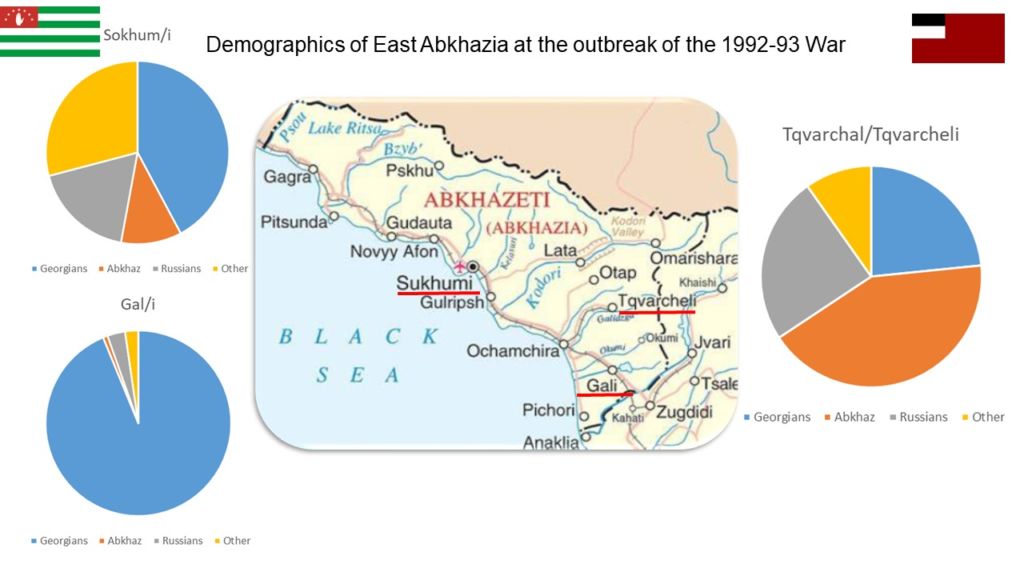

[26]This chart shows eastern Abkhazia’s demographics in the summer of 1992. The Georgians were dominant in all the major towns.

But by the 1980s the Soviet Union was fraying badly, although few outsiders saw this. The collective farms weren’t productive, the insurgency in Afghanistan was draining away Soviet manpower, and the senior leaders were dying off. The nuclear accident at Chernobyl in 1986 was so catastrophic that it couldn’t be hidden. All of these factors led to speech restrictions being lifted and some economic liberalization.

This turned out to be a salvation for the Abkhazis. In the 1980s they started to organize against their displacement. Anastasia Shesterinina documents the paths that individual Abkhazis took to political activism. For example, the Georgians had all the best jobs and even trained Abkhazis didn’t stand a chance of getting hired. Georgian doctors were not kind to Abkhazi patients. One young man studying in a library was set upon by a group of Georgians just for being there. The worst were the Georgian tourists, who would get drunk and attack the local Abkhazis only to then be let go by the police. In professional settings, things were usually calmer, but as one Abkhazi remembered, “We could morn or celebrate together in everyday life. But what concerned us separated us.” By 1986, the ethnic conflict was open, but it hadn’t become violent — yet.

In 1989, as the Soviet world started to dissolve, violent clashes in Abkhazia began. The first were in Gagra in March. Then there was a dispute over the reorganization of Abkhaz State University that escalated into violence in July in Sukhumi. Georgian militias moved against them but were stopped by the intervention of Soviet troops.

These clashes were not as important as the Lykhny gathering [28] of March 18, 1989, however. 30,000 Abkhazis gathered and their political elite signed an appeal that was sent to Moscow calling for the restoration of Abkhazia as a Soviet Socialist Republic independent of the Georgian SSR. It was this metapolitical event which organized the Abkhazis into a potent political force, and gave all of them an aim to strive for.

More importantly, the Lykhny gathering gave the Abkhazis some semblance of legitimate control over their government. This turned out to be critical. It provided order to the Abkhazis and allowed them to act independently from Tbilisi. Meanwhile, the Soviet Union continued to unravel. Then, in August of 1991, there was an attempt by Communist hard-liners in Moscow to overthrow Gorbachev and end the reforms, but the coup failed. At the same time, the Georgian SSR was rocked with internal turmoil until Eduard Shevardnadze, a high-level minister in the Soviet government, became President of Georgia.

Shevardnadze organized an invasion of Abkhazia to suppress their drive for independence. On August 14, 1992, Georgian Marines attacked the western portion of Abkhazia, while Georgian armored columns drove into Abkhazia from the east. The Abkhazis were initially uncertain of what was happening, but they began to mobilize.

The Abkhazis didn’t have much to fight with. The Georgian SSR, like all Communist governments, had sought to keep the population disarmed. There were a few secret caches of small arms and some men had hunting rifles, but they had no tanks or heavy weapons. But they were motivated to fight given that they feared their imminent extinction at the hands of the Georgians.

The Russians were divided about what to do as the fighting escalated. Some favored the Georgians, some the Abkhaz. The situation across the Caucasus Mountains was highly fluid, and the Russians were uncertain as to how this would affect them. Some Caucasian nations increasingly allied with Russia during the 1990s while others became more hostile. Eventually, enough local Russian commanders provided military supplies to the Abkhazis as the situation clarified to help them before it was too late. The Abkhazis also received support from other Caucasian nationalist movements.

For their part, the Georgians were well-armed from the outset, although a large part of their military’s manpower came from emptying the jails, so it was less than ideal. Additionally, the Georgians were not particularly well-trained. Despite having a prominent former Soviet official as President, Georgia’s domestic political scene remained unstable. Published Georgian accounts of the battles — often fought by civilians — describe a well-aimed base of fire laid upon Georgian positions, forcing them to withdraw.

By September of 1993, the Abkhazis had beaten back the Georgian military and captured their capital, Sukhumi. Thousands of Georgians fled in the aftermath. In war, truth is the first casualty, and from the Georgian point of view, the Abkhazi soldiers went on a campaign of rape and murder. There is very likely some truth to this, although it seems that most of the Georgians had fled before ever encountering enemy soldiers. The one thing that is certain is that the Abkhaz were deadly serious about taking back their country.

Today, in part due to the ethnic cleansing of Georgians, the Abkhazis’ gains have not been legitimized in the eyes of most of the world. Their territory is still considered part of Georgia by most of the United Nations’ member states.

A guess as to why the Georgians fled so quickly rather than standing and fighting is that their settlements in the region were unprofitable. They probably needed infusions of aid from the Georgian SSR to prop up their colonies’ economy. When the Soviet Union fell apart, they became financially desperate enough to flee rather than fight. (This is also a factor in the American Great Replacement, of course: non-whites are subsidized at every level.)

The US has kept out of the Abkhazis’ conflict, since Americans don’t have a dog in the fight. And despite pronouncements from anti-Russian hawks in the US government such as (thankfully) deceased Senator John McCain, we are not “all Georgians.” The Georgians were not significantly repressed by the Soviet Union. Indeed, a case can be made that they were critical junior partners in the Bolshevik affair. Their government was and is reckless, corrupt, and prone to getting involved in disastrous wars. And as for Abkhazia, I certainly don’t plan on visiting.

The Abkhazis’ plight is not much different from that of American whites today. Incorporating Abkhazia into the Georgian SSR in 1931 had an effect on the former not unlike that which the American 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Immigration Act had on white America. Both led to considerable demographic and cultural displacement of the original majority in each place.

Just as in Abkhazia under the Soviets, white advocates are being deplatformed and are sometimes even made political prisoners while sub-Saharan-fueled violent crime is endemic and often deliberately aimed at whites. The Great Replacement is as obvious in America today as it was in Abkhazia then. The destruction of monuments and statues in the cities of America in 2020 is no different from the suppression of Abkhaz culture.

The Abkhazis had several advantages Americans don’t have, though. They were fortunate in that they didn’t have a culture of Georgian worship such as Americans have regarding Negroes. Regardless, if the Abkhazis could reverse Stalin’s policies — the cruelest Emperor of the cruelest and most Leftist of tyrannies — so too can white Americans reverse their own dispossession.

It is up to American white advocates to develop a metapolitical framework for a white ethnostate which all whites, regardless of age, sex, or condition, can strive towards. Doing so could prevent further displacement and a calamity such as the Abkhaz war of 1992-93.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[30]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[30]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.

Note

[1] [31] Anastasia Shesterinina [32], Mobilizing in Uncertainty: Collective Identities and War in Abkhazia (Ithaca & London: Cornell University Press, 2021).