Richard Dreyfuss & Once Around

Posted By Edmund Connelly On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledRecently I wrote about the thoughtful comedy Keeping the Faith, which, in my view, does a remarkable job of exploring the conflicts involved in Gentile-Jewish relations. Stiller’s other Gentile-Jewish comedy from the same year, Meet the Parents [2] (2000), shows even more open hostility between Gentiles and Jews.

This theme of conflict between the two camps has been dealt with by many authors, including John Murray Cuddihy, whose Ordeal of Civility admits in the title that Jews living among Gentiles is not always a picnic for those involved. (By the way, though the full title of the book suggests it is Jews who endure an ordeal, the body of the book shows that it is more Jews who visit various ordeals upon the goyim, a fact which many Jewish reviewers at the time noticed, while Gentiles were either silent about it or missed it.)

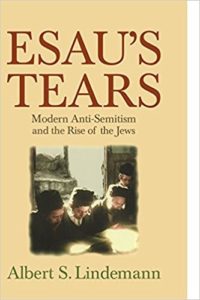

In the academic sphere, one modern book which courageously addresses modern relations between the two groups comes from the Harvard Ph.D. Albert Lindemann. His book Esau’s Tears: Modern Anti-Semitism and the Rise of the Jews (Cambridge, 1997) came at an important time for me and informed much of my understanding of The Jewish question. (Read Kevin MacDonald’s TOQ review here [3].)

Until discovering that book, I don’t believe I was aware of the biblical character Esau, let alone Jacob. Over the last two decades, however, the archetypes of Esau and Jacob have become important for me because in so many ways their interactions accurately represent the strained relations between Europeans (portrayed as the brawny, hairy Esau) and Jews (portrayed as the trickster Jacob). When we meet them in Genesis 25, we learn that the Lord said unto Rebecca, “Two nations are in thy womb, and two manner of people shall be separated from thy bowels . . .” In that biblical story, Jacob, the younger brother, had sown seeds of discord by betraying his brother and father, setting the stage for thousands of years of discord. I find it fascinating that Jews created this foundational myth.

[4]Lindemann’s book is courageous in that it is a post-Second World War examination that honestly details actual Jewish behavior, much of which is harmful to non-Jews. Lindemann (who is not Jewish) also obliquely chastises those who incorporate the Holocaust narrative into the wider story of Jewish “suffering-history” — the lachrymose view of Jewish history also known by the German word Leidensgeschichte. Because he was unwilling to present a simplified account of “Jews are victims, goyim are bad,” he was predictably attacked but thankfully survived.

[4]Lindemann’s book is courageous in that it is a post-Second World War examination that honestly details actual Jewish behavior, much of which is harmful to non-Jews. Lindemann (who is not Jewish) also obliquely chastises those who incorporate the Holocaust narrative into the wider story of Jewish “suffering-history” — the lachrymose view of Jewish history also known by the German word Leidensgeschichte. Because he was unwilling to present a simplified account of “Jews are victims, goyim are bad,” he was predictably attacked but thankfully survived.

For instance, Robert Wistrich, the Jewish professor of theories of anti-Semitism, wrote about Esau’s Tears [5]:

It is one thing, however, to recognize that Jews have interacted with their persecutors in complicated ways, and wholly another to present them as largely responsible for the irrational hatreds to which they have so often fallen victim. Yet that is what Albert S. Lindemann, a history professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara, has now done in this deeply pernicious book.

Attacks petered out after that, so in a sense, this Cambridge University-published book was given the seal of approval, and I turned back to it with renewed interest. And for me, the title of Lindemann’s book became more important after I’d read MacDonald’s trilogy on Jews, which gave me the intellectual courage to look directly at real Jewish behavior and the ability to put aside incessant Jewish screeching that they were always and forever innocent.

I’ll never forget the epiphany I had about this as I was returning from a day of solo back-country skiing in deep powder late one December. The Sun had set and the woods were starting to darken, and as I trudged through snow past my knees, I kept thinking about the title of Lindemann’s book: Esau’s Tears: Modern Anti-Semitism and the Rise of the Jews. I’m embarrassed to admit it now because it’s so obvious, but as I struggled with why Esau was crying — why European Christians had suffered so much — I realized it was because of Jewish behavior. Ostensibly, the phrase in the title “The Rise of the Jews” is meant to refer to the explosion of the Jewish population in Europe prior to the First World War, but upon reading the book, one quickly realizes that it means not just that, of course, but also “The Rise of Jewish Power.” In other words, when Jews exercise power over Gentiles, intense pain for the latter will follow.

Then, following MacDonald’s thesis in his trilogy’s second book, Separation and Its Discontents, I realized that modern anti-Semitism was actually a reasonable reaction to harmful Jewish behavior. Esau shed tears because Jews since Napoleonic emancipation have been tearing down Gentile civilization, robbing European nations of their patrimony, and causing great death and destruction in general. Esau is well within his rights to shed tears — and exercise self-defense.

Ever since, I’ve seen Gentile-Jewish relations in ways diametrically opposed to the conventional narrative we’ve been hit over the head with for well over a century. That’s why I’ve made so much effort to show how Jews impose this dishonest narrative through their grip on the media.

Finally, I come to the Hollywood film that dramatizes this Gentile-Jewish conflict, this kulturkampf, this cosmic battle between archetypes. What makes it fascinating is the fact that it’s a film crafted by Gentiles and by all appearances chronicles the just-mentioned struggle without even being aware of it. So either I’m totally off base, or we have a genuine cultural manifestation of this epic clash springing from the subconscious of our society. And because of that, it can be all the more accurate and profound.

Now the facts: Once Around was written by Malia Scotch Marmo [6], who has an Italian-American background. The director is the Swede Lasse Hallstrom. Thus, we have no sign of Jewish input into the genesis of the film, which I think is important.

Here is the plot: A young woman from Boston, Renata Bella (played by Holly Hunter), is leading a rather carefree life until her sister gets married. Seized by the moment, she corners her long-time boyfriend and asks him if he will marry her. When he finally admits he will never marry her, Renata is understandably crushed, and to take her mind off this shocking turn in her life, she flies to the Caribbean to attend a seminar on how to sell condos. (Watch the trailer here [7].)

There she meets the star of the seminar, one Sam Sharpe from New York City. Though short in stature, he is preternaturally confident, boasting without shame about his sales abilities (among other things). Sensing an opportunity, Renata switches name cards and ends up sitting next to the far older man; immediately, they fall in love.

And the actor playing Sam Sharpe is Richard Dreyfuss, which is crucial to the reading of the film.

[8]Because Sam is wealthy, he has a chauffeured limousine which he uses to convey Renata to her home in Boston, where we learn more about Renata’s Italian-American family. Lead by paterfamilias Joe Bella (Danny Aiello), this family unit is strong, but Renata’s subsequent marriage to Sam gravely tests this strength.

[8]Because Sam is wealthy, he has a chauffeured limousine which he uses to convey Renata to her home in Boston, where we learn more about Renata’s Italian-American family. Lead by paterfamilias Joe Bella (Danny Aiello), this family unit is strong, but Renata’s subsequent marriage to Sam gravely tests this strength.

As Rotten Tomatoes [9] reports, “Sam’s well-meaning but obnoxious insistence on insinuating himself into every aspect of Renata’s life rubs the rest of her family the wrong way.”

Here, however, is where absolutely every film reviewer gets Once Around wrong, for by missing the obvious fact that Dreyfuss is playing a Jewish character, they are mystified by the entire point of the film. Yet many reviewers still loved the film without understanding why. Roger Ebert [9], for instance, confessed that Once Around was “the first movie in a long time to leave me speechless.”

It is my contention that these professional reviewers realized at a deeper level that they were watching the mixture of love and pain caused when a Jew enters into the wider family of Gentiles, but they either couldn’t admit it publicly or weren’t even aware of it themselves. In the remainder of this essay, I will make my case that this is a quintessential story of Jews sojourning among the goyim, replete with the pain Jewish behavior inevitably visits on the host nation.

To make my case, I will claim that Richard Dreyfuss is one of those actors who essentially plays the same role in every movie in which he appears because he inevitably plays himself. Since he is so full of Yiddishkeit, so bursting with its richness, his movie roles are also full of unadulterated Yiddishkeit, whether the character he is playing is specifically Jewish or not. As film expert Kathryn Bernheimer tells us in The 50 Greatest Jewish Movies, Dreyfuss is an actor “who has consistently applied his distinctly Jewish persona to a wide variety of roles . . .”

In one sense, it is not surprising that he has such a strong Jewish persona, since his “thespian career had begun in a Chanukah play” (Stephen J. Whitfield, American Space, Jewish Time [Milton Park, Oxfordshire: Routledge, 2007]). Since that youthful performance, he has gone on to play a long line of Jewish characters (as well as other non-Jewish characters full of “Jewishness”). For example, he played a “sleazy entrepreneur” in The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz (1974), an Israeli soldier in Victory at Entebbe (1976), a Jewish private eye named Moses Wine in The Big Fix (1978, and a lawyer named Levinsky in Nuts (1987). In 1993 Dreyfuss starred in Neil Simon’s semi-autobiographical Lost in Yonkers, playing the role of Uncle Louie, a crook on the run, as well as the Jewish gangster Meyer Lansky in HBO’s Lansky (1999).

[10]

[10]You can buy Son of Trevor Lynch’s White Nationalist Guide to the Movies here [11]

In other movies, Dreyfuss’ characters may not be specifically Jewish or they may be veiled to varying degrees. In Down and Out in Beverly Hills (1986), for example, he seems to be playing (together with Bette Midler) a Jewish Hollywood type in the Paul Mazurksy-directed and produced satire of the neurotic lives of the Hollywood rich and famous. In What About Bob? (1991), is his character, psychiatrist Leo Marvin, Jewish? One could argue that he is. In his much more famous roles in Jaws and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, his high-energy persona can easily be seen as an extension of his Yiddishkeit.

Despite all this, no reviewer made the connection between the very Jewish Richard Dreyfuss, Yiddishkeit, and Sam Sharpe, despite the fact that it’s staring them in the face from the moment Sam makes his appearance. The failure to recognize this is as egregious as missing the fact that Dustin Hoffman played a Jewish role in the 1967 hit The Graduate, which I reviewed here [12].

All the while the evidence was there, beginning with Dreyfuss’ own explicit 1987 claim (in Lester D. Friedman, The Jewish Image in American Film [New York: Jewish Media Fund, 1996]), an admission that is critical to my entire essay:

I am immensely proud of being Jewish, to the point of bigotry. . . . I was raised in Bayside which is ninety percent Jewish. I went every week to Temple Emanuel from the time I was nine until I was sixteen. . . . In a sense, everything I do has to do with my being Jewish.

Repeat that to yourself: “Everything I do has to do with my being Jewish.” So why did viewers miss this when he played an abrasive Jew from New York four years later in Once Around? Well, I didn’t miss it when I watched the film soon after it came out, and I feel I’ve been totally vindicated in the quarter century since: Sam Sharpe is a Jewish character, a fact central to the film’s entire drama. Further, as I’ve stated, this makes Once Around a seminal Hollywood product cataloguing a modern example of the 3,000-year story of Jews among the goyim.

Now let us return to the plot of the film. As we saw, once back home, Renata introduces Sam to her parents; the problem is that Sam is cut from totally different cloth than the Bellas, who are a mixture of Italian (the father) and northern European (the mother). Sam is pure Yiddishkeit, and it leaves the Bellas speechless at first. For example, when Sam first meets Renata’s father, he leaps out of his limousine, strides up to him, and says, “Let me shake the hand of the first man my little rosebud ever loved.” Then, when Renata’s brother Tony arrives in his working-class Trans Am, Sam gives him a too-familiar shoulder knock when they meet.

This kind of overfamiliarity and coarseness continues. For example, he invites a belly dancer to Mr. Bella’s birthday party, something this staid family would never have imagined. When the newlyweds return from their honeymoon, Sam imparts a blessing upon the staid aging parents: “I hope you both have a lifetime of great sex and joy.” This is similar to his role in The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz, where Dreyfuss “gives a fabulously shaded performance as the likable loser. His Duddy is charming and annoying, vulnerable and arrogant, nervy and nervous.” In Once Around, Dreyfuss’ character once again exhibits these same traits, which is because Sam Sharpe is as obviously Jewish as the explicitly Jewish Duddy Kravitz. I again ask: How could every film reviewer have missed this?

Here I am going to stray from my usual contention that Hollywood movies where the Jewish man gets the shiksa exhibit hostility toward Gentiles. Rather, I will argue that Once Around has a powerful tragic element because Sam Sharpe, the Jew, is not a bad guy. He is sincerely generous and good-willed toward Renata and her family, and soon he will suffer a near-death experience, which only deepens the sense of tragedy as this outsider, this man with “differences,” continues to intrude upon and hurt the Bella clan.

To support my claim, I will now unpack the background to Sam’s “difference,” and not just by saying he’s a Jew. Rather, it has to do with a central characteristic of Jewry in their long sojourn among various goyim, a characteristic called “wearing a mask,” or employing various strategies to blend in with the particular host culture among whom they may find themselves. It may also be understood as assimilation, though we have great reason to suspect that it is not often an honest attempt at assimilation. At its most developed phase, it may be scientifically understood as crypsis, which Kevin MacDonald has discussed in The Culture of Critique [13], writing that “Jewish crypsis and semi-crypsis are essential to the success of Judaism in post-Enlightenment societies.”

With only a little reflection, most readers should be able to bring to mind many examples of Jews in movies “wearing a mask.” Author Patricia Erens, for one, in The Jew in American Cinema draws attention to a scene about masking in Woody Allen’s film Zelig (1983). In the scene, New York Intellectual Irving Howe explains how the character Zelig, who can change himself into any character he so desires, “represents the ultimate assimilated Jew.” As the son of a Yiddish actor, Zelig “metamorphosizes into everything from a Black trumpeter, to an opera singer, to a baseball player, to an American Indian, to a Nazi. . . . In terms of its Jewish content, Zelig represents the most devastating film about Jewish assimilation ever produced.”

(For those interested in an extended discussion of this topic, I recommend Eugene Borowitz’s The Mask Jews Wear: The Self-Deceptions of American Jewry.)

We see this masking in Once Around when the diminutive Dreyfuss suddenly claims to have descended from a “long line of Lithuanian generals,” and in a later scene, he tells Renata that “When I was eight years old, I used to stare at the photo of my grandfather who was a general in the Lithuanian army.” I’m sorry, but it is absurd to think of Dreyfuss as the descendent of a Lithuanian general.

Remarkably, there is a scholarly essay that examines the issue of Lithuanian identity in the film under discussion. Called “The Lithuanian Angle in a Hollywood Movie: An Analysis of ‘Once Around, [15]’” it appeared in the Lithuanian Quarterly Journal of Arts and Sciences in 1993.

Like all movie reviewers, however, the scholar who wrote the essay, William Wolkovich-Valkavicius, failed to understand that Sam Sharpe is a Jewish character and instead stretched to celebrate all things Lithuanian in the film. Wolkovich began his essay by writing, “Let’s begin with a basic question. How did screen writer Malia Scotch Marmo happen to attribute Lithuanian roots [15] to the principal male character?” My view is that Marmo got it wrong, though likely unintentionally. No wonder Wolkovich is perplexed throughout his essay.

Notice his confusion as he tries to fit a square Jewish peg into a round Gentile hole when describing one scene:

Here too we have an example of considerable poetic liberty. When I prepared the translations of the English fragments given to me, I pointed out the anomaly of a belly dancer speaking Lithuanian. Such an entertainer is unknown in Lithuanian culture. Even so, the incongruous sequence stayed in place because of the importance of the scene. Here one might give a mild interpretation by surmising that the dancer is not an ethnic Lithuanian, but rather a gypsy with Lithuanian forebears.

Why the need for “poetic liberty”? Why an “anomaly,” or “incongruous sequence”? Well, it’s because Sam Sharpe is not descended from Lithuanians: He’s a Jew. Wolkovich begins to get close when he writes about “a gypsy with Lithuanian forebears,” but gypsy is the wrong ethnic group; she’s a stand-in in for Jews.

Once again we see Wolkovich struggle with identity. No wonder he gets it wrong:

In one case, license turned into total fiction. Joe Bella and his family have gathered in a restaurant for a meal in memory of his deceased mother. Sam disrupts the solemn mood by grabbing the microphone, hoping in vain to sing a Lithuanian melody. He remarks: “I’m going to sing a Lithuanian song about motherhood. It’s about a mother who is completely devoted to her son who is going on a journey. Everything she does — the cooking and cleaning is done for her son.” In fact, his description of the folk song is totally different from the actual text that he later does sing. In any case, Renata’s mother, Marilyn Bella, angrily gets him to sit down.

Wolkovich has to use phrases like “total fiction” and “totally different” because he has no idea that Sam Sharpe is a Jew masking as someone else. Wolkovich was so close to understanding Sharpe’s identity when he noted in his essay that actor Richard Dreyfuss is Jewish, but the closest he can get to making the critical link is “Sam Sharpe proves to be a somewhat shadowy figure ‘of unexplained origin,’ as one critic observes.”

Yes, it is unexplained because it is a Jew masking as someone else, a quintessential Jewish skill.

This failure to understand Sharpe’s Jewish identity was endemic. Film critic David Denby, for example, was also on the right track when trying to pin down Sharpe’s identity within the Mediterranean but got it wrong by almost a thousand miles when he titled his review [16] of Once Around, “Zorba the Lithuanian.” Denby is this close to identifying Sam Sharpe as Jewish when he writes, “Dreyfuss is irrepressibly noisy — until the big emotional moments, when he turns irrepressibly mawkish.”

Oh, the humanity! We are talking a Jew here!

Next, let us further consider how Robert Ebert failed to understand Sam Sharpe’s character:

This man Sam Sharpe is some piece of work. He has an unfailing touch for saying the wrong thing in the wrong way at the wrong time. All of his gestures are intended to be warm, kind and generous, but he has the kind of style that grates the wrong way — he puts your teeth on edge while you’re trying to smile back at him. . . .

Richard Dreyfuss creates a character who is so difficult, so impossible, so offensive, that it is easy to dislike the personality and forget how good the performance is. But this is some of Dreyfuss’ best and riskiest work — he’s out there on the edge, with this suntanned, chain-smoking, larger-than-life case study.

Again, observe Ebert’s confusion:

Watching the coming attractions trailer for Once Around a few weeks ago, I observed to myself that it had not given me the slightest clue as to what this movie was about. Watching the movie, I have the same impression. It’s an odd, eccentric, off-center study of some very strange human natures, and at every turn it confounds our expectations for them.

Of course, Ebert hadn’t the slightest clue because he missed the key fact that Sam Sharpe was a Jew. Again, I insist that my contention about this Jewish identity explains what this fascinating film is all about.

Now we can return to the second half of the film, where we feel the intense discomfort caused by Sam’s presence. Scene by scene, an undercurrent of unease grows. As mentioned before, it nearly erupts when the family holds a memorial service for Grandmother Bella. Joe Bella, clearly moved by the solemnity of the occasion, sings a heartfelt tribute to his late mother, and the audience listens in silence.

[17]

[17]You can buy James O’Meara’s End of an Era here [18].

Sam, however, jumps out of his seat, grabs the microphone, and prepares to sing his own, more upbeat tribute. Mrs. Bella realizes that this would destroy the sacredness of the memorial, so she practically commands Sam to sit back down, uttering what will become the mantra for the remainder of the film: “Sam, you’re tearing us apart.” Even then, Sam is too insensitive to appreciate what she and the others feel, too thick-skinned to take Mrs. Bella’s rare command as anything more than the normal give and take of life. These different cultures do not mix well.

Still, the tug of love is powerful. Sam and Renata get married and neither has ever been happier. Soon, a child arrives, but the issue of the baby’s baptism ignites the most destructive fight the extended family has ever experienced. Because of his “different religion,” Sam insists that the baptism must be on a specific date, but other family members have planned a well-earned holiday beginning on that day. Around the family table, they try to reach a compromise, but Sam’s deafness to the others drives them to rage. Finally, Mr. Bella, almost broken by the tragedy of it, sends some of the couples home, then sends Sam to wait in the car. To his daughter he says in a near whisper, “Sam’s a wonderful man. He’s a generous and kind man, but he’s killing us. He’s killing us.” Does not such tension mirror that created when Jews enter among Gentile nations? Just ask Esau.

This unique variant of “Christianity” surrounding the baptism may be seen as a signifier of that forever marginal character in the human drama: the Jew. This story at one level is about the contact and collision of cultures in modern America. Sam never really understands why he does not fit in, but symbolically he must pay for his transgressions. At the baptism of his son, he suffers a heart attack, and from here on he must keep his exuberance in check.

Unlike other films I’ve reviewed, including those with the Jewish man-shiksa pairing, Once Around is not an attack on Gentile society. Rather, it is a lucid portrayal of any Gentile society that finds itself with Jews. What is fascinating is the fact that here it is the Jew who is symbolically punished for creating so much pain. Further, Dreyfuss succeeds brilliantly in creating a believable tension between living the life of the old Sam, an unvarnished Jew, and recognizing the limits the Gentile world puts on him. From the time of his heart attack, Sam experiences a much fuller humanity, one far richer in nuance and certainly in irony. Because he has grown in this way, he is able to reassume a place at the large family table of the Bella family. Some tensions still exist, but a mature love and respect has been reestablished between Sam, his wife, and her family.

The Heat of a Cultural Clash?

Sam Sharpe is a tragic character, and an undoubtedly Jewish one at that. Consider what the late Ernest van den Haag wrote about Jews in The Jewish Mystique:

Jews are human. We all are, but Jews are in a sense more human than any one else: they have witnessed and taken part in more of the human career, they have recorded more of it, shaped more of it, originated and developed more of it, above all, suffered more of it, than any other people. No other nation has witnessed so much, argued and bargained so much, and yet clung to its own inner core as much as the Jews have. . . . For over 2000 years now they have dazed, dazzled, and befuddled the world.

Now consider that Sam Sharpe is a member of just such a tribe and has brought with him those ancient memories and anxiety. Suddenly, Once Around becomes far more comprehensible, and we viewers can for once experience a true cultural revelation. Sam has “dazed, dazzled, and befuddled the world” as shown to us by what he has visited upon the Bella family.

What pathos, what sheer honesty we see as the film revolves around the line, “Sam, you’re tearing us apart.” Or, “Sam’s a wonderful man. He’s a generous and kind man, but he’s killing us. He’s killing us.”

Dear reader, can one deny that the same is true about what today’s Jews are doing to us literally and culturally? We are the Bella family, but Jews have suffered no modern punishment in the way that Sam Sharpe does with his heart attack, nor have modern Jews paused to reflect on their harmful behavior in the way Sam does. In this instance, Once Around takes a happier turn than Western life has in general.

Let me now swing back to the beginning of this review where I discussed the Old Testament story of Esau and Jacob. Recall that the Lord said unto Rebecca, “Two nations are in thy womb, and two manner of people shall be separated from thy bowels . . .” In that biblical story, Jacob, the younger brother, had sown seeds of discord by betraying his brother and father, yet reconciliation follows. Similarly, in Once Around, as we saw, reconciliation follows.

Still, I am not totally comfortable with the way Albert Lindemann used the story of Esau and Jacob to bookend his tome. Though thoroughly detailing the immense harm done to Gentile nations through corrupt and harmful behavior by Jews, Lindemann employs this interpretation of the biblical story:

Contrary to what might seem the logic of the story (that Jacob and Esau would live in ever-lasting enmity), after the passage of twenty-two years, Esau, in meeting his now penitent brother, put aside his resentment, and the two were reconciled.

Even a brief reading of Wikipedia’s [19] account of Genesis shows that Lindemann may have been too kind:

After the encounter with the angel, Jacob crosses over the ford Jabbok and encounters Esau who seems initially pleased to see him (Genesis 33:4 [20]), which attitude of favour Jacob fosters by means of his gift. Esau refuses the gift at first but Jacob humbles himself before his brother and presses him to take it, which he finally does (Genesis 33:3, 33:10-11 [21]). However, Jacob evidently does not trust his brother’s favour to continue for long so he makes excuses to avoid traveling to Mount Seir in Esau’s company (Genesis 33:12-14 [22]), and he further evades Esau’s attempt to put his own men among Jacob’s bands (Genesis 33:15-16 [23]), and finally completes the deception of his brother yet again by going to Succoth and then to Shalem, a city of Shechem, instead of following Esau at a distance to Seir (Genesis 33:16-20 [24]). The next time Jacob and Esau meet is at the burial of their father, Isaac, in Hebron (Genesis 35:27-29 [25]). The so-called reconciliation is thus only superficial and temporary.

Frankly, that strikes me as more realistic when considering the possible outcome of the Jewish-Gentile kulturkampf going on throughout the world. I just don’t see genuine reconciliation in the cards. I see continuing conflict instead, which is why I appreciate the following quote from Rabbi Arthur Hertzberg in Jews: The Essence and Character of a People:

We understand why Jews have preferred explanations of anti-Semitism that focus on the moral imperfections of non-Jewish majorities. It is more comforting to believe that the Jew-haters, in all their wickedness, have no shred of a reason — even a bad one — for their angers. It is far more difficult for Jews to accept the idea that anti-Semitism may be, fundamentally, the heat of a cultural clash.

I’ve long examined the Gentile-Jewish cultural clashes Hollywood films have shown, with the overwhelming majority blaming Gentiles. Once Around, however, shows it far more like it really is, with the Jewish presence creating conflict and pain. I suppose it was inevitable that this could only be achieved accidentally, as there is no evidence that the two Gentile filmmakers involved with the film’s creation knew what they were portraying, and the message went completely over the reviewers’ heads.

The casting of Richard Dreyfuss was necessary for the alchemy to work, and today we have a testament to the real tragedy of Jews trying to mix with Gentiles. It just isn’t working well.

This article [26] is reprinted with the permission of The Occidental Observer [27].

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[28]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[28]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.