Oliver’s Capitulation

Posted By Spencer J. Quinn On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled1,412 words

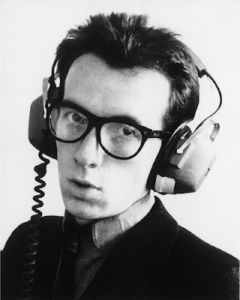

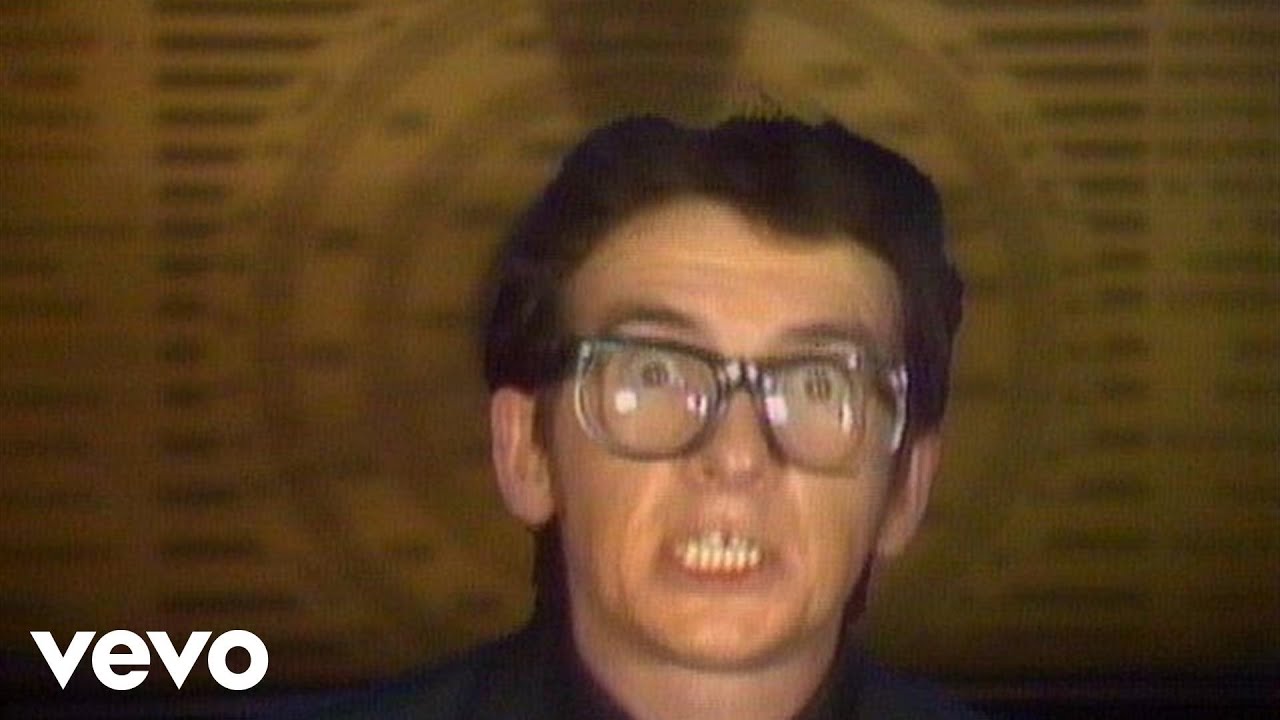

Earlier this year, rock star Elvis Costello announced [2] that he would no longer play his 1979 hit “Oliver’s Army” in concert. Further, he entreated radio stations not to play the song at all. Why? Well, the song uses the word “nigger,” which is now so toxic and taboo that most white songwriters dare not use it, regardless of context. And Costello prefers this to rewriting the lyrics or hearing the word bleeped on the radio.

“Oliver’s Army,” [3] which appears on Costello’s album Armed Forces, is an excellent song, and this is one reason for my sadness at its self-cancellation. As is typical in many of Costello’s lyrics from that period, what is said is not always what is meant, and what is meant is not always exactly clear. Costello at his best was unrivalled at this kind of layered songwriting, almost to the point where the listener braces for the trenchant irony even while enjoying the song’s catchy melody and creative arrangement. “Oliver’s Army” takes this kind of pop-song sophistication and offers a profound take on something extremely important and pervasive: globalism.

Granted, it deals with imperialism, which is an antiquated form of globalism and was more or less on the outs by the time the song was written. However, since all forms of globalism require men with guns in exotic places to enforce them, it’s not much of a stretch to apply “Oliver’s Army” to today, especially when it comes to the strategically overreaching United States. The song references Britain’s armed forces in places all over its former empire, and ends with an ironic advertisement for a career in the military:

But there’s no danger

It’s a professional career

Though it could be arranged

With just a word in Mister Churchill’s ear

If you’re out of luck or out of work

We could send you to Johannesburg

How’s this for a rewrite?

With just a word to Mister Bush’s dad

If you’re out of luck or out of work

We could send you to Baghdad

The song takes its title from Oliver Cromwell, who helped lead Britain’s first standing army in the seventeenth century and used it to subjugate and occupy Ireland. Costello being Irish (his real name is Declan McManus), and having witnessed firsthand some of the Troubles in Belfast, he most likely had a great deal of emotion mixed up with a sense of history repeating itself in his nation of origin.

But, genius songwriter that he is, Costello sings the song in part from the perspective of someone serving in the British Army:

Don’t start that talking

I could talk all night

My mind goes sleepwalking

While I’m putting the world to right

Call careers information

Have you got yourself an occupation?

Oliver’s army is here to stay

Oliver’s army are on their way

And I would rather be anywhere else

But here today

There was a Checkpoint Charlie

He didn’t crack a smile

But it’s no laughing party

When you’ve been on the murder mile

Only takes one itchy trigger

One more widow, one less white nigger

And this is where Costello shouldn’t get in trouble, but does. Of course, there’s nothing wrong with this lyric, although “itchy” tends to describe a finger on the trigger, not the trigger itself. (But I digress . . .) “White nigger,” on the other hand, is a real historical term which the British sometimes used to refer to the Irish. In a recent interview [4], Costello recalls how his Irish Catholic grandfather was smeared with that epithet while serving in the British Army during the First World War. A songwriter has every right to include such a powerful and loaded term in verse. If anything, the term “white nigger” is what makes “Oliver’s Army” such a gut-punch of a number. With these two words, Costello poignantly expresses a jaded and dangerous worldview, exaggerated or not, which had much to do with some of the more painful chapters in British history.

Anyone taking offense at this is either historically ignorant or — and here we get to the crux of this essay — anti-white. The very same people who would cancel Elvis Costello turn a deaf ear when black rappers use the same word whenever they please and in the vilest manner imaginable. This racial double standard is so glaringly obvious and self-serving on the part of our corrupt, anti-white elites that for this reason alone, “Oliver’s Army” should be played as often as possible — along with John Lennon’s “Woman is the Nigger of the World,” Randy Newman’s “Rednecks,” Patti Smith’s “Rock n’ Roll Nigger,” and Guns N’ Roses’ “One in a Million.” Maybe we should start using the word “niggardly” in every other sentence and arrange public readings of Joseph Conrad’s The Nigger of the Narcissus and Flannery O’Connor’s The Artificial Nigger just in case we didn’t get our point across. And of course, there’s always Huckleberry Finn.

It makes me sad that Elvis Costello would cancel himself like this. It makes me sadder to conclude that many of the rock icons we grew up with are really not the daring iconoclasts we once thought they were. All along, they were just kids thumbing their noses at their out-of-fashion elders while getting laid as often as they could. During the 1960s and ‘70s, most of them had no idea of the damage their rebellious attitudes were causing. And now, when real oppression comes a-knockin’ and they’re forced to reap the whirlwind they helped sow, they fall in line like the conformists they always were. Remember in the late 1970s when Costello played his hit “Radio Radio” [5] on Saturday Night Live after producer Lorne Michaels told him not to? He was banned from the show for a whole decade.

What a rebel.

Certainly, some of these kids had talent and made lasting music. But none of them predicted the apocalyptic cancel culture we’re living in today — with one possible exception: Elvis Costello.

Maybe it was inadvertent, but “Radio Radio” just might be the most prescient song of the rock era. In it, Costello’s conformist alter-ego praises the Orwellian mind control coming from the radio, almost to the point of surrender:

Radio is a sound salvation

Radio is cleaning up the nation

They say you better listen to the voice of reason

But they don’t give you any choice

‘cause they think that it’s treason.

So you had better do as you are told.

You better listen to the radio.

Since no Elvis Costello song is complete without layers, the man’s rebellious id chimes in during the song’s bridge:

I wanna bite the hand that feeds me.

I wanna bite that hand so badly.

I want to make them wish they’d never seen me.

But in the end, the conformists get their ironic victory:

Some of my friends sit around every evening

and they worry about the times ahead

But everybody else is overwhelmed by indifference

and the promise of an early bed

You either shut up or get cut up;

they don’t wanna hear about it.

It’s only inches on the reel-to-reel.

And the radio is in the hands of such a lot of fools

trying to anaesthetize the way that you feel

Wonderful radio

Marvelous radio

Wonderful radio

Radio Radio . . .

Of course, the song rocks gloriously [6].

I challenge all rock fans out there: Is there a mainstream rock song from the 1960s or ‘70s that better encapsulates cultural Marxism as enforced by our media oligarchs today? Replace “radio” with CNN, Amazon, Facebook, Google, Twitter — you name it, and the song still makes sense. In fact, as pervasive as the censorship and deplatforming coming from these entities have become over the past two years, “Radio Radio” makes more sense now than ever before. You think the 2020 election was stolen? You think the January 6 protestors got a raw deal? Oh, that’s treason, all right. You think the COVID vaccines shouldn’t be trusted or that vax mandates are tyrannical? Well, “you better listen to the voice of reason.” And do you, God forbid, wish to use any of these platforms to tell the truth about race or speak out on behalf of white people? Then “you either shut up or get cut up, they don’t wanna hear about it,” and that’s all there is to it.

The fact that the author of this brilliant song is now capitulating to the insidious forces he decried in it over 40 years ago is a tragic irony — an irony perfectly worthy of Elvis Costello.