My Fair Enemy: Pitched Battles & Love Affairs with the Worthy Opponent, Part 2

Posted By Kathryn S. On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled4,140 words

Part 2 of 2 (Part 1 here [2])

Battle of the Sexes: Femmes Fatales Walking the Streets and Roaming the Moors

Relationships can bring men and women lots of joy. They can also cause a lot of pain and suffering, and sometimes simultaneously. This section is dedicated to those who have discovered that their worthy opponent was the man/woman they loved. And hated.

Enter Dashiell Hammett, a Left-wing activist author with some very Right-wing sensibilities, and the father of American mid-century noir. Among his characters were the happily (and boozily) married couple Nick and Nora of Thin Man (1934) — and some decidedly unhappy couples like Sam Spade and Brigid O’Shaughnessy of The Maltese Falcon (1930). The latter novel (and later filmed adaptation with Humphrey Bogart and Mary Astor in the starring roles) was a mystery surrounding the murder of Spade’s partner and the elusive Maltese Falcon, a 400-year-old statuette allegedly made by the Knights of Malta out of gold and jewels and then captured by pirates before it could reach its intended recipient, Philip II of Spain. The piece had been missing since then — until now. But before Spade could untangle the many-layered plot to retrieve the Falcon, he fell for O’Shaughnessy, herself deeply involved in the international murder and recovery scheme.

By the time Spade discovered that his lover had been the one pulling his and most of the other strings the whole time, he was a torn man with bloodshot eyes — drunk on desire and anger in equal measure. It had come to this: either he or his femme fatale were going to prison for murder. Oh, “It’s easy enough to be nuts about you,” he said, looking “hungrily from her hair to her feet and up to her eyes again,” but he wouldn’t “play the sap,” even if a part of him wanted to cry: “to hell with the consequences and do it” anyway. And he wouldn’t do it, because, “Goddamn you — you’ve counted on that with me the same as you counted on that with the others!” He might be “sorry as hell” and suffer a few “rotten nights,” but they would pass. It seemed that more than love, earning her respect (and keeping his own self-respect) as a worthy opponent — by not “playing the sap” like all “the others” — mattered more to Spade, in the end. As they heard the sirens coming, he tenderly brought his hands up and around her slim throat and confessed, “I hope to Christ they don’t hang you, precious, by that sweet neck.”[1] [3] O’Shaughnessy was “still in his arms when the doorbell rang.” The battle of the sexes was always fought dirty.

Presumably, either a few “rotten nights” or the hangman’s noose put a stop to the love affair between Sam and Brigid. But poor old Lockwood walked into an even messier romance that not even the grave could end. The interwar streets of San Francisco might not have seemed to have much in common with the early nineteenth-century English moors, but they both specialized in star-crossed lovers, in both brutish men and selfish women.

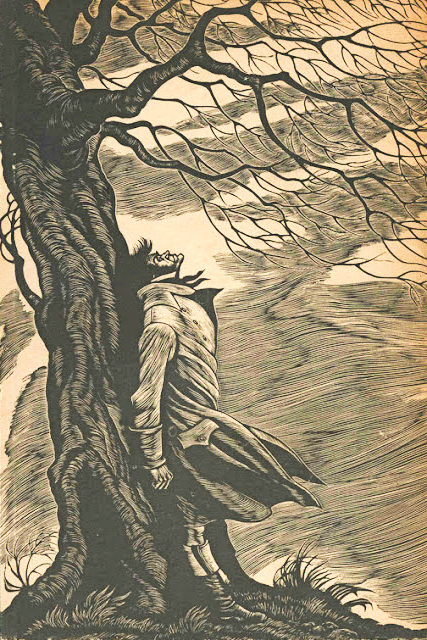

Speaking of “rotten nights,” Lockwood’s first one at Wuthering Heights, the manor belonging to the dark and unpleasant Heathcliff (more recently, this classic love story has been marred by modern filmmakers and playwrights interpreting Heathcliff’s slight swarthiness to mean “African”), was not exactly restful. During the small hours, he heard a ghostly voice through the windowpane call out, “I’m come home: I’d lost my way on the moor!” Then, an arm plunged through the glass, pulling at the frightened man, “Let me in! . . . It is twenty years . . . I’ve been a waif for twenty years.”[2] [4] A sane person would have left the moors behind on the morning’s first carriage, but Lockwood instead stayed and learned who haunted the mansion, and whom she haunted.

Two decades earlier, Catherine (Cathy) Linton/Earnshaw had died, leaving her rejected paramour mad with anger and grief. As she lay taking her last breaths, she used them to curse Heathcliff: “‘I wish that I could hold you,’ she continued, bitterly, ‘till we were both dead! I shouldn’t care what you suffered. I care nothing for your sufferings.’” For Cathy, dying wasn’t the problem. It was the possibility that Heathcliff might forget her. Would he “be happy when [she was] in the earth?” Would he say 20 years afterwards at her grave that he had “loved her once . . . [but] many others since?” Would he, or would he not, rejoice upon his own death that he was “going to her,” and sorry to be leaving Wuthering Heights and life? Yes, she tortured him with a “wild vindictiveness.” In return he accused her of being possessed by the devil, “to talk in that manner to [him] while [she was] dying.” Was it insufficient for her “infernal selfishness” that he would be “writhing in the torments of hell,” while she was at peace? To a spectator they looked like enemies in thrall to one another — a “fearsome picture.” After some time, Cathy settled down and extended her trembling hand to Heathcliff. No, she was not wishing him any greater torment than she would suffer in the tomb, she said more gently. She wished only for them “never to be parted . . . forgive me,” she cried.[3] [5]

But forgiveness would be a long time coming, for her jealousy was matched by his bitterness at her “betrayal,” at the way she left him in the “abyss,” a “liar to the end!” Just as she had on her deathbed, he cursed her with torment, with an unrestful grave. “Haunt me then!” he yelled at the wind, “dashing his head against the knotted trunk” of a tree and howling, “not like a man, but like a savage beast being goaded to death with knives and spears.”[4] [7] And since the only worthy opponent he’d ever had, the only person he’d ever cared about, was gone, he had to content himself with exacting revenge on everyone else around him, including the next generation of Earnshaws and Heathcliffs. Meanwhile, Cathy’s apparition continued to scratch at his window until finally she could claim him again. This was not love, readers, nor was it hate, but something scarily else.

A Higher Law: Church & State, Court & Conscience

Western history, art, and literature are filled with confrontations with the law, or between lawgivers. Complex societies cannot function without order, without a code governing the behavior and protecting the interests of its members. Civilization is law. No sane person wishes to live in an anarchic, lawless place. But as we know, the law can be weaponized; it can become not about the common good, but about politics; not about justice, but the personal power and pride of a few men. Something we should revere and uphold somehow gets twisted into something we fear and despise. This very old love-hate relationship with the law has unsurprisingly manifested as well in the form of the worthy opponents: the one representing the state and the other a different, or “higher,” law. It is wrong to think of the law as something sterile, black and white, or passionless. No, the story of the law and its battles have aroused just as much zeal, just as much fire, as any battle between the sexes.

[8]

[8]You can buy Kerry Bolton’s More Artists of the Right here. [9]

In medieval England there were three law codes operating simultaneously: the civil law of the King and his ministers, canon/Church law, and the Common Law of custom and precedent. English history from the Middle Ages through the early-modern period can be seen as a series of attempts to eliminate one of them or to combine these three codes into a single charter, culminating in the unique English constitution as enshrined in Parliament. In the 1100s under King Henry II, it was often a hot war between these triple mandates, particularly for a controlling king such as Henry, who saw his mission as a centralizing one. It is the opinion of this author that Henry II was a great (and likable) king. Had he been a little greater — or a bit weaker –, he might not have died a broken man, having alienated each of his old friends and his entire family who all in the end rebelled against his authority. But at the time of his friendship with his Chancellor, Thomas Becket, all this lay in the future. Henry never had a better or closer companion than Becket, a man of rather common lineage, who owed his success to the King and to his own industriousness. According to contemporaries, the two men were always together — eating, hunting, carousing. Indeed, “In all Christian times, two men never lived in closer harmony.”[5] [10]

But all was not well. The Church had become a thorn in Henry’s side. At that time there were thousands of clerics working for the Church in England, and whenever one of them broke the law — even if it was a civil law, like theft or rape — they were tried in ecclesiastical courts; the King could not touch them, and they more often than not got off with nothing more than a slight slap on the wrist, or a small fine. Ecclesiastical courts could also excommunicate anyone, even nobility, without the King’s permission — a very serious interdict in those days. This offended many people, but as any law-keepers would, the bishops guarded their territory jealously; give in to the civil courts, and their liberty, the sacred power of the Church, would rapidly diminish. So, when the Archbishop of Canterbury died, leaving the most important ecclesiastical post in England open, Henry seized the opportunity to appoint his beloved friend Thomas Becket to the office. Finally, he would have an ally in his quest to force the clerics to bend the knee to him, rather than to God (or to their own interests). Henry could not have been more wrong.

In the “year of grace 1162, on the eve of Pentecost . . . feast of the Church of Canterbury” and before all his bishops, “Thomas was declared free and absolved of all secular obligations and presented to the Church of Canterbury by Henry the son and heir of Henry II King of England and by Richard de Luci and other English nobles representing the King, who was abroad.”[6] [11] And he proceeded to take his new obligations very seriously. His diet became monkishly abstemious, and he began to mortify his flesh with a hair shirt, filled with vermin, beneath his princely vestments — an undergarment that he never washed or removed, even in sleep, or even after he had subjected his back to the lash. It was a complete transformation. Henry II was shocked. At every turn, his old friend stymied the King’s goal of bringing the canon law under his secular aegis. Thomas humiliated him in public, and twice he did so before the King of France (an unforgivable affront in the eyes of any English ruler). Soon, a personal, loving friendship had turned to a personal, white-hot hatred, driven by both men’s pride.

At one point, Henry allegedly raged to his subordinates, “Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest?!”[7] [12] Four of his knights took his question to heart, rode to Canterbury Cathedral, and in the house of God brutally murdered His high priest Thomas Becket, claiming to be acting on the authority of the King. The shockwaves were immediate; all of Christendom was scandalized, and Henry — once one of the most powerful monarchs in Europe — became a political leper. Though he did expensive penance; though he built Becket a shrine at which he humbled himself; though he walked there barefoot in the snow, allowed several church brothers to flog him, and then prayed for forgiveness face-down on the cold tiles for hours before his former intimate — nothing for Henry went right after that. Thomas, his worthy opponent, was dead, but not defeated. Three years after his brains had been splattered across Canterbury’s altar, Pope Alexander III made him a martyred saint. Meanwhile, that same year Henry’s oldest son, joined by his younger brothers and the Queen herself, Eleanor of Aquitaine, rose up in rebellion.

Across the Channel and nearly 700 years later, and the conflict over the letter of the law and conscience was still a compelling one — compelling enough for Victor Hugo to write about it in his masterpiece of 1830s France, Les Misérables (1862). By that time, canon law had greatly weakened as opposed to the secular law as represented by King Louis Philippe and the French Parlement. But the the Catholic Church’s cultural power was still strong. The story revolved around the battle of wills between Jean Valjean (also known as M. Madeleine), an escaped ex-convict once imprisoned for stealing a loaf of bread; and Inspector Javert, the unbending physical manifestation of civil law who had made it his personal mission to find and recapture Valjean. The former man might have remained bitter and destitute, but after being caught stealing Bishop Myriel’s silver, the churchman saved Valjean from the police and second conviction, giving him more precious candlesticks, besides. But there was a catch: Valjean needed to earn his newfound freedom and wealth by dedicating himself to God.

This Valjean tried to do it by becoming a benevolent factory owner and rescuer of impoverished single mothers [14]. It frequently happened that “when [Valjean] was passing along a street, calm, affectionate, surrounded by the blessings of all, a man of lofty stature . . . [there] followed him with his eyes until he disappeared, with folded arms and . . . his upper lip raised in company with his lower to his nose” a man whose name was Javert, “and he belonged to the police.” You see, Javert had been born a bastard in prison, and as he grew older, he “despaired of ever re-entering” society. But he discovered a truth: that the community “exclude[d] two classes of men, — those who attack[ed] it and those who guard[ed] it.” As he had “no choice except between these two” groups, and conscious of his own natural “rigidity, regularity, and probity, complicated with an inexpressible hatred for the race of bohemians whence he was sprung,” he chose to be a watchman. Javert was a man composed “of two very simple and two very good sentiments . . . but he rendered them almost bad, by dint of exaggerating them” — that is: a “respect for authority, [and a] hatred of rebellion.” These sentiments had enveloped him “in a blind and profound faith every one who had a function in the state, from the prime minister to the rural policeman.” On the other hand, “he covered with scorn, aversion, and disgust every one who had once crossed the legal threshold of evil. He was absolute, and admitted no exceptions.”[8] [15] Valjean, the nemesis who had escaped his punishment, no matter what respectable and moral life the man as M. Madeleine lived now, deserved no mercy, only the galleys.

And so followed a long cat-and-mouse game amidst the cholera epidemic and the 1832 June Rebellion in Paris. When Valjean finally had his enemy “under his pistol” and in his power to kill, in order to set himself free of the policeman who had haunted him and his children for years, he “fired into the air, instead of blowing out his brains.” Valjean, that “unhappy wretch [was] an admirable man!” the inspector discovered to his horror. He was “the providence of a whole countryside! . . . Javert’s saviour!” He was “a hero! He [was] a saint” who, like Becket, followed his conscience over the laws of his King.[9] [16] He was, the hunter realized in a fit of lucid madness, the worthier opponent, the better man, following the higher law. After this, nothing for Javert went right. Now that the chase, the passion that had given his life meaning, was done, what else was there left for Javert but to drown himself in the cholera-infested sewer waters between the Pont au Change and the Pont-Neuf?

Thine Own Best Enemy: Potions & Portraits Bring Out His “Good” Side

Nineteenth-century thinkers and authors loved to imagine the bare thinness of the sheet that separated man from beast, the civilized from the savage. You see, this age was the apogee of Western progress and empire. There was a new invention almost every week, and everywhere European man saw advertisements for white soap, cleanliness, day spas, and posters for the “civilizing mission” that was a holy burden he should take up for the sake of a dark planet. But did evolution — another optimistic nineteenth-century theory — proceed in one direction only? No, Darwin’s world was not one of evolution, but adaptation. How could anyone having witnessed Britishers and Dutchmen “going native” while playing the “sahib” in the equatorial jungles not also believe in devolution? Even the primmest lady’s unconscious mind hid violent and sexual secrets from her conscious self. But these repressions never really went away, always returning to haunt her dreams at night and to drive her to weird tics and hysterics during the waking hours. And looking around at the monocoled men in their swishy suits and hats –always going to the opera in their carriages, picking out handkerchiefs, or bowing to strangers in the streets –, maybe these peacocks needed a bit of the barbarian infusion to thicken their inbred blood. Victorians feared and admired, loved and loathed the savage. What happened when the worthiest and most frightening opponent was one’s self?

[17]

[17]You can buy Collin Cleary’s Wagner’s Ring & the Germanic Tradition here. [18]

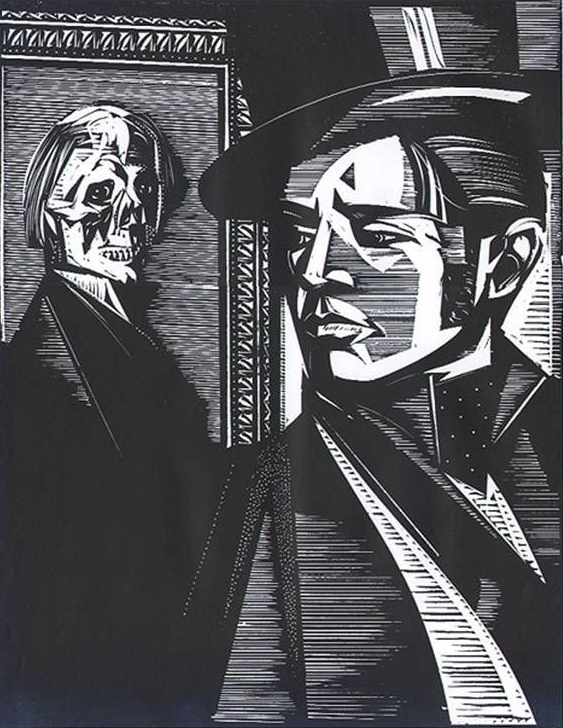

It seemed that 1880s London had a problem: There was a mysterious and unpleasant-looking man who called himself Mr. Hyde terrorizing the city, trampling young children, and beating members of Parliament. He was “pale and dwarfish, [and] he gave an impression of deformity without any nameable malformation . . . the man [seemed] hardly human!” There was something “troglodytic” about him, a devolved, foul sort of aspect. If ever there was “Satan’s signature upon a face,” Mr. Hyde had it. Why was the respectable Dr. Henry Jekyll leaving everything in his will to such a person? This was the central question that opened Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886). Jekyll’s friend and barrister investigating the matter speculated that though Jekyll had been “wild when he was young,” that was a long time ago. Nevertheless, it must have been “the ghost of some old sin, the cancer of some concealed disgrace . . . years after memory [had] forgotten and self-love condoned the fault” that now drove Jekyll to associate with Hyde, to adopt him as a son and heir.[10] [19]

In truth, Jekyll had found the chemical means of separating the evil half of his personality from his whole nature, of making the fiend manifest. When he had first downed the potion, “The most racking pangs succeeded: a grinding in the bones, deadly nausea, and a horror of the spirit.” But those agonies subsided to a sensation “indescribably new and, from its very novelty, incredibly sweet.” Jekyll felt younger, lighter, happier in body, “conscious of a heady recklessness, a current of disordered sensual images running like a millrace in [his] fancy.” No longer was he a repressed slave to obligation and morality, but he knew freedom of the soul. He also knew himself to be “more wicked, tenfold more wicked, sold a slave to [his] original evil; and the thought, in that moment, braced and delighted [him] like wine.” He had discovered Mr. Hyde.

But Hyde had gradually begun to take over the rest of the doctor’s self. It became harder to transform back into Jekyll, and as the doctor withered in health and stature, Hyde grew in boldness and height. Jekyll had unleashed a monster within himself — a form that he both loved and hated to take on. What to do? Should he “cast in [his] lot with Jekyll” and die of abstinence to “those appetites which [he] had long secretly indulged and had of late begun to pamper?”[11] [20] Or would he choose Hyde, and thus “die to a thousand interests and aspirations, and to become, at a blow and forever, despised and friendless?” In the end, there was really only one option: to become a “self-destroyer,” the killer at a single stroke of both man and monster.[12] [21]

Dorian Gray well understood the lure of a narcissistic, sensual life. But he did not want to live it as an unkempt, nasty-looking devil like Mr. Hyde. No, he wanted to live forever as a beautiful young man of 22 or 23 — to live just as the admiring artist Basil Hallward had painted him. The worldly Lord Henry was also impressed by the youth’s allure. But instead of paying him empty compliments, he gave Dorian a warning. Yes, Mr. Gray, “the gods have been good to you,” he admitted. “But what the gods give they quickly take away.” Dorian had only a few years in which to enjoy his looks, “in which really to live.” When his youth went, his beauty would disappear with it, and then he would discover “that there [were] no triumphs left for [him],” or he would have to content himself “with those mean triumphs that the memory of [his] past [would] make more bitter than defeats.” Every new Moon that waxed and “every month as it wane[d]” would bring Dorian “nearer to something dreadful.” Time itself was “jealous of him, and war[red] against [his] lilies and [his] roses . . . “ Dorian needed to realize his youth “while [he had] it” for a season or two of golden days. “A new hedonism, — that is what our century wants!”[13] [23] Lord Henry declared to the stunned and trembling young man.

From then on, Dorian embraced “the new hedonism” and left a trail of broken hearts and broken lives in his wake. He even became murderer. The victim was the painter of his portrait, Basil Hallward, who had discovered what had happened to his picture and the young man to whom it was dedicated. The image had become Dorian’s mirror — the true state of his soul and the reminder of the foul bargain that Dorian had made in order to keep up his appearances, to preserve his good looks. A sudden “exclamation of horror broke from Hallward’s lips as he saw” in the lurid light, “the hideous thing on the canvas leering at him. There was something in its expression that filled him with disgust and loathing. Good heavens! it was Dorian Gray’s own face that he was looking at!” If it was true, that this was a window into the state of Dorian’s soul, Basil decided, then his friend “must be worse even than those who [spoke] against [him] fanc[ied him] to be!”[14] [24] In a moment of hatred truly directed at himself, Dorian stabbed the painter to death.

He became furtive and paranoid. Though he’d gotten rid of Basil’s body and cleaned the knife perhaps hundreds of times, still there was one piece of evidence against him: the picture, the proof of Basil’s own signature and Dorian’s own deeds. Why on earth “had he kept it so long? It had given him pleasure once to watch it changing and growing old.” But of late “he had felt no such pleasure. It had kept him awake at night.” This ugliness had taken over his life, this other half had consumed him and taunted him from behind its curtain. Just as he’d seized the knife in a fit of passion to kill the artist, so he would kill the artist’s picture. He ripped the canvas violently from top to bottom. When the authorities and servants finally entered the locked room, “they found hanging upon the wall a splendid portrait of their master as they had last seen him, in all the wonder of his exquisite youth and beauty. Lying on the floor was a dead man, in evening dress, with a knife in his heart. He was withered, wrinkled, and loathsome of visage.”[15] [25] Dorian, who’d loved himself like no other since Narcissus, grew to hate his own reflection very much unlike Narcissus; but just as the Greek youth and Dr. Jekyll had before him, so he too became a “self-destroyer.”

And one more thing before I leave you, readers, to contemplate that fair enemy for yourselves: kiss — don’t kill — the worthy white one who loves you!

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[26]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[26]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.

Notes

[1] [27] Dashiell Hammett, The Maltese Falcon (New York: Vintage, 1972), 114-115.

[2] [28] Emily Brontë, Wuthering Heights (1847), 39-40.

[3] [29] Ibid., 254-55.

[4] [30] Ibid., 268.

[5] [31] William Fitzstephen, An Annotated Translation of the Life of St. Thomas Becket, Leo T. Gorde, ed. (June 1943), 31.

[6] [32] Ibid., 48.

[7] [33] The exact phrase Henry uttered was hotly contested; contemporary Becket biographer Edward Grim claimed that the King roared, “What miserable drones and traitors have I nourished and brought up in my household, who let their lord be treated with such shameful contempt by a low-born cleric?”

[8] [34] Victor Hugo, Les Misérables (1862), 357-50.

[9] [35] Ibid., 2698.

[10] [36] Robert Louis Stevenson, The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886), 12.

[11] [37] Ibid., 58-61.

[12] [38] Ibid., 46.

[13] [39] Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray (Victoria, BC: McPherson Library Special Collections, 2011), 38-9.

[14] [40] Ibid., 134.

[15] [41] Ibid., 160-61.