Bridging the American Political Divide

Posted By Morris van de Camp On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledSeth David Radwell

American Schism: How the Two Enlightenments Hold the Secret to Healing Our Nation

Austin: Greenleaf Book Group Press, 2021

It is no secret that the American political scene is polarized. The last two election cycles have brought considerable political violence — most fueled by the Democratic Party and its mainstream media enablers. Recently, Seth Radwell, a Manhattan businessman, took several years off work to write a book that explores this divide.

Radwell argues that America’s political divide goes back to the Enlightenment. The Enlightenment started in Western Europe as early as the 1670s, arguing for greater participation in government by the people, the rejection of religious explanations for otherwise mysterious matters, the seeking for answers based on science, and so on. Proving that an institution’s foundations are undermined while it is still at its height, the ideas of the Enlightenment began to be disseminated during the time of absolute monarchy in Europe, when the sectarian bloodbath of the Thirty Years’ War was still within living memory.

One can read a great deal about the French, Scottish, English, and other accounts of the Enlightenment, but Radwell says that nationality doesn’t matter. Rather, the most important aspect of the Enlightenment is the division within it between radicals and moderates. The radicals were willing to bring everything down to achieve their utopian goals, while the moderates only sought possible reforms at the margins — fixing that which could be fixed but doesn’t break something else.

Radwell writes that

[t]he split between the Moderate and Radical Enlightenment thinkers was of huge historical significance in France and . . . in America. While at first the split was only polarizing, the schism became permanent after the storming of the Bastille in 1789. In the ensuing conflict, remaining neutral was not a viable option. The Moderates lined up in support of the existing monarchy (albeit with new controls), while the Radicals advocated for an entirely new system. “The Bastille’s fall thus exacerbated but also clarified the long-standing rift between the two now openly competing Enlightenment wings. (p. 84)

[2]

[2]The storming of the Bastille created a permanent split between the factions of the Enlightenment.

John Adams & the Moderates

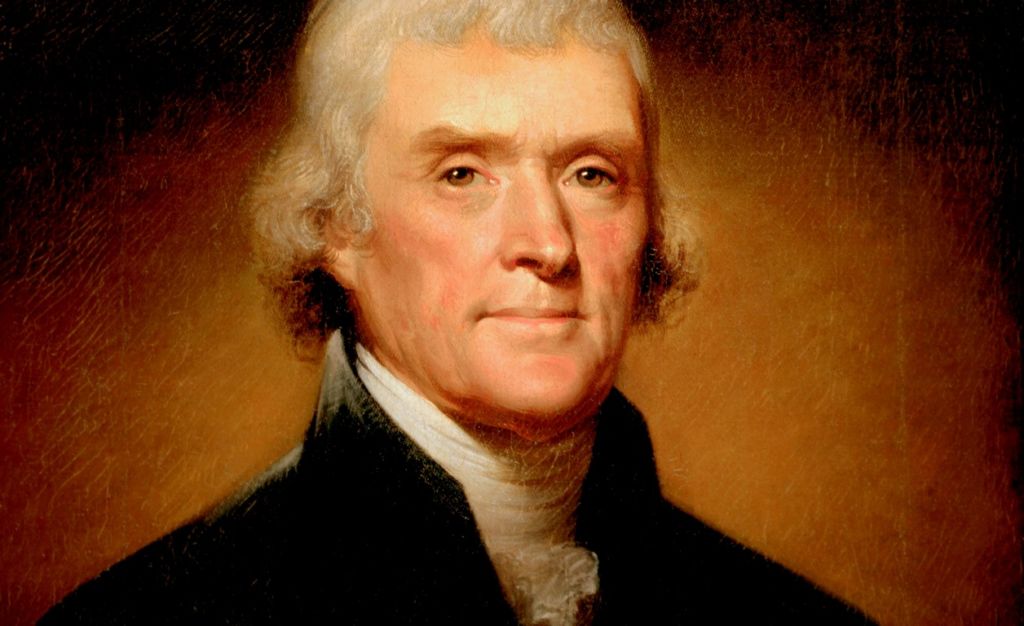

In the early United States, the moderates were best represented by John Adams, Alexander Hamilton, John Dickinson [3], and George Washington. The radicals were best represented by Thomas Jefferson, Thomas Paine, and Benjamin Franklin.

John Adams was a consistent moderate throughout his career. His first splash on the national scene was when he successfully defended the British soldiers who participated in the “Boston Massacre.” In that trial, Adams argued that the soldiers were right to defend themselves. His closing arguments [4] were not much different from those used to exonerate Kyle Rittenhouse. Radwell writes:

Thus, in the mid-1770s, while Adams and many other colonial leaders were striving for a higher level of autonomy for the colonies, they were doing so fully under the auspices of this existing British constitution, which had well-defined provisions for governing the remote parts of the British Empire. This was the colonial leaders’ existing frame of reference. Interestingly, in interpreting the writings of John Adams, many modern readers have confounded references to “violations against the Constitution,” believing Adams was referring to the Constitution of the United States, which of course had not yet been written. In fact, Adams was referring to violations against the British constitution that had been established after the 1688 Glorious Revolution. Similarly, in Adams’s writings, many mentions of “The Revolution” referred to the same English Glorious Revolution [5], not the American Revolution, as many modern-day readers suppose. Therefore, since colonial leaders had the British mixed-government model as their frame of reference, the accusations against the Crown for which they demanded redress emphasized a failure to apply the principles of Britain’s own constitutional monarchy to the American colonies. (pp. 89 & 90)

Alexander Hamilton famously supported complex financial institutions, paying off debts to large central banks, and protecting industry through tariffs. He would prove to influence George Washington through the first President’s two terms, and he would influence — albeit in a tenser way — John Adam’s presidency.

Jefferson & the Radicals

Thomas Jefferson was the ideological polar opposite of Adams and Hamilton. He wholeheartedly supported the Radical Enlightenment and helped write the French Revolution’s Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen [7]. Jefferson’s religious freedom bill in Virginia has come to be seen as liberating for the dissenting radical Protestants settling in western Virginia in colonial times — but his primary goal was freedom from religion.

The Declaration of Independence, although edited by others, was written by Jefferson. The document was filled with Radical Enlightenment ideas, especially the “equality” clause and the use of the term “Creator” rather than “God” or “Divine Providence.”

Thomas Jefferson needs a critique from the Right. Wilmot Robertson wrote of Thomas Jefferson:

Perhaps more than any other American, Jefferson must assume the responsibility for loading American democracy with the ambiguity and cant that have pursued it down to the present day. When one of the largest slave owners in Virginia solemnly writes, “all men are created equal,” either his semantics or his integrity must be called into account. What Jefferson and most of the other signers of the Declaration of Independence meant by equality was that English colonists had the same natural right to self-government as the English in the mother country. But that is not what they wrote. And it is what they wrote that, carried forward to another century and used in another context, has proved to be such an effective time bomb in the hands of those who advocate projects and policies totally antithetical to Jeffersonian democracy.[1] [8]

[9]

[9]If Pickett’s Charge was the price the South paid to get Robert E. Lee, “all men are created equal” is the price America paid for Thomas Jefferson.

Robertson wrote of Radical Enlightenment Pamphleteer Thomas Paine:

Thomas Paine deserted his wife and then filed for bankruptcy. Next he deserted his country, England, went to America, then returned to Europe, where he helped stir up the revolutionary terror in France. In 1796 Paine accused Washington of treachery, a libel which in no way has shaken Paine from his lofty pedestal in the modern liberal pantheon . . .[2] [10]

Thomas Jefferson was a contradictory man. His remarks about sub-Saharans in Virginia are no different from what one might find at American Renaissance. His political success was probably due more to his ability to play political hardball and his support for white expansion in North America than his Radical Enlightenment ideology. Jefferson was stunned to see the French Revolution devolve into a bloodbath.

[12]

[12]Radwell claims that Jefferson’s opposition to the Alien and Sedition Acts was a key factor that got him elected. It may have been Jefferson’s pro-white actions that proved the winning issue. Once in office, Jefferson accomplished two important pro-white feats. The first was purchasing the Louisiana Territory for three cents an acre. The second was sending the US Navy and Marines to suppress Islamic piracy and slave raiding in North Africa.

Radwell argues that the French Revolution’s Reign of Terror was the result of Maximilien Robespierre harnessing reactionary, Counter-Enlightenment forces — including the clergy — against the French radicals rather than a flaw in his ideology. (I found this to be a bold claim, to say the least.)

The US Constitution is a product of the Moderate Enlightenment. Instead of “equality” and the “pursuit of happiness,” it favors “ourselves and our posterity” and “property.” Many of the Washington administration’s actions, outside of the Indian Wars in the Ohio Country, were driven by fears of a French Revolution-style explosion in America. The suppression of the Whiskey Rebellion and the Adams administration’s Alien and Sedition Acts were reactions to the Reign of Terror.

Radwell downplays these events in the United States, but political violence was a very real menace — especially, to use his term, Radical Enlightenment-inspired political violence.

A great deal of the book discusses the Enlightenment split in politics up to the Trump administration. There has been an oscillation between the Radical and Moderate wings that has crystalized in the Democratic and Republican parties. Radwell argues that Trump was so effective because he exploited the neoliberal globalist economic conditions that have wreaked havoc on so much of America’s industrial heartland and the white middle and working classes.

[13]

[13]Deindustrialization and globalization are major factors in America’s current political situation. The impact of globalization and outsourcing was not widely noticed at first, but when industrialized China emerged as a global rival, supply chains could be disrupted by unseen forces and a broad swath of the population in the heartland became underemployed, as well as victims of opiate addiction and crime.

President Trump governed as a run-of-the mill Republican once he got into office. He roared loudly, but didn’t get as much done. Radwell attributes this to the “Conservative Dilemma.” This is when the economically-squeezed middle and working classes are fooled into voting for policies that favor the wealthy through the politicization of social issues. Radwell is on to something here. The Conservative Dilemma is a puzzle yet to be solved. Greater support for trade and industrial schools, industry and manufacturing in America, and tariffs will go a long way in solving the issue, however.

Healing the Divide

[14]

[14]You can buy Greg Hood’s Waking Up From the American Dream here. [15]

Radwell shows that Adams and Jefferson came to understand each other’s point of view in their old age, and there is something almost holy about the fact that these two political rivals both died on the same day: July 4, 1826. Much of the political tension in America today could be healed if each side would hear the other’s point of view. One group that Radwell endorses is Braver Angels [16], which is attempting to highlight the similarities between Americans and shore up the crumbling political center.

As you can well imagine, a book that attempts to accommodate both sides of an issue will draw some considerable criticism from either side. I’ll add mine here. Its weaknesses are that Radwell believes the mainstream media sees bureaucracies such as the Justice Department and the “intelligence community” as neutral agencies rather than as political players like the Praetorian Guard was in ancient Rome. He also thinks that sub-Saharans are being politically suppressed rather than what they really are: vastly overrepresented. He also blames the “Right” for violence, when it is clear that antifa and Black Lives Matter have been the most violent force since 2014.

His cues from the mainstream media cause him to focus on Trumps “lies,” so he misses the bigger lies. The Big Lie of the last two decades has already been executed: the second Bush administration’s “weapons of mass destruction” fraud. George W. Bush colluded with Jewish/Zionist neoconservatives, the “intelligence community,” and the mainstream media to invade Iraq to pursue Israel’s interests. The disasters which followed need not be recounted here. He also neglects the lies behind black police “victims” such as the late aspiring rapper Michael Brown and the sub-Saharan saint/career criminal George Floyd.

Finally, Radwell wishes to abolish the Electoral College and the Senate. While I instinctively support these institutions as the mos maiorum of my people (who were in Pennsylvania when the Constitution was written), I must recognize that a unicameral legislative body can more easily vote to make a white ethnostate a reality and establish a “white citizens’ militia,” which can then in turn be given more funding than the current Department of Defense. Miracles can happen in politics, after all! Oliver Cromwell’s greatest weapon was the Rump Parliament.

Apart from these criticisms, this book should be seen as an enormous vindication of our ideas. Radwell acknowledges that immigration is a problem and that America has a unique culture which is being harmed by open borders. While he doesn’t believe that the 2020 election was stolen, he does acknowledge that voting irregularities are an issue, and he offers some ideas to put things right.

Most importantly, he mentions the plight of the white working class. This is the central issue in American politics. Deindustrialization, the contempt and sneering directed at them by the elites of both parties, drugs, and criminal predation are enormous issues. Addressing them means addressing trade imbalances, economic inequality, and sub-Saharan crime. After all, it is working-class whites and white Hispanics who are victimized by African criminal predation more than anyone else. America’s biggest strides have always occurred when either segregation and/or the mass incarceration of sub-Saharans has been state policy.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[17]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[17]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.

Notes

[1] [18] Wilmot Robertson, The Dispossessed Majority (Cape Canaveral, Fl.: Howard Allen Enterprises, 1981), p. 316.

[2] [19] Ibid., p. 113.