A Tale of Two Fires & the Fall of Old Rome

Posted By Kathryn S. On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled6,722 words

It was the summer of 79 AD. The celebrated naturalist and Roman navy admiral Pliny the Elder sat on an outcrop and looked toward the western sea, lit with the fires of a setting Sun as if he was taking stock of a life well-lived, and the once-and-future prospects of his beloved country. To the east, also set briefly ablaze like a torch in the purpling sky, he could see Vesuvius: reliable, peaceful Vesuvius. Yes, Pliny had witnessed a slew of momentous events in what was perhaps the most dramatic era of ancient Rome’s storied past: with the exception of Augustus, he’d served the Julio-Claudian dynasty from first to last,[1] [2] in all their triumphs and during all their misadventures. In particular, he recalled the trauma of the Great Neronian Fire that had, only 15 years prior, razed a city and ruined an emperor. So, it was comforting to know that some things would never change.

As a naturalist, the Elder Pliny had always been fascinated with the four elements — fire, “the highest of these,” in particular.[2] [3] Among the most notable wonders he’d studied over the course of his career was that “dreadful” comet observed by the “Æthiopians” and the Egyptians during the reign of King Typhon. Its flame had a “bloody appearance,” and was “twisted like a spiral; its aspect was hideous, nor was it like a star, but rather like a knot of fire.”[3] [4] Sometimes, he explained, “there [were] hairs attached to the planets and the other stars” that foretold great disasters, “as was the case with the civil commotions” during both the war of Pompey and Cæsar, as well as Octavian’s consulship. During his own age and “about the time when Claudius Cæsar was [assassinated] and left the Empire to Domitius Nero, and afterwards, while the latter was Emperor, there was one which was almost constantly seen and was very frightful.”[4] [5] According to tradition, the shape and direction of these flying star-flames revealed secret, usually horrible destinies. Romans lived in a numinous world, full of dreams and prophecies; a mystical world that not even the rational Pliny could ignore. If the comet “resembl[ed] a flute,” he explained, “it portend[ed] something unfavourable respecting music”; if it appeared phallic, its message was “something respecting lewdness of manners.” And if it formed a “triangular . . . figure . . . someone [would] be poisoned.”[5] [6] As Pliny surely knew, these were all allusions to the many scandals that had blighted the late “Domitius Nero’s” reign.

But perhaps the most awful and mysterious marvels of all were the mountains where “nature rag[ed], threatening to consume the earth.” Among them, in the region of Phaselis, the mountain Chimæra burned “with a continual flame, day and night,” and in the country of Lycia, the mountains of Hephaestius burned “so violently, that even the stones in the river and sand” smoldered like coals. The Æolian isle of Hiera blazed spectacularly during the Social War “for several days . . . throwing out flame that consum[ed] everything.” Indeed, he wrote in amazement, “in so many places, and with so many fires, does nature burn the earth!”[6] [7] Of course, Pliny reflected, man was also very capable of setting “the earth” ablaze, of decimating his cities. He didn’t yet know it, but his own life would, in many ways, be a tale of two fires that wasted, in turn, many cities; the one lit by man, and the other by a terrible black god who’d been roused to restlessness atop a very familiar peak. Both marked a turning point in the history of antiquity, for they became in the popular imagination two iconic symbols of Old Rome and its lost world; the charred remains and heat-warped grates and human bones keeping a wrecked, but eternal vigil beneath 2,000 years of debris; and waiting patiently there for our own ambitions to join them.

While Rome Burned

No one had suspected that the teenaged Emperor was a monster.

When Nero Claudius Cæsar assumed the Imperial title in 54 AD and at the age of 16, everyone had high hopes for the future. Nero was energetic, handsome, and he made pretty love words to both senators and plebeians. A golden age after the unstable reigns of Caligula and Claudius seemed to follow behind the white chariot he drove through the streets of Rome, as if he were Phaethon himself. But by the mid-sixties, Nero’s reign had curdled. Even if we discounted three-quarters of the Emperor’s alleged outrages as the result of smear campaigns — first launched by resentful senators, then taken up by the Flavians and their chroniclers, and finally immortalized for posterity by the Catholic Church — we would still be left with a repulsive figure. There are “good” kinds of ruthlessness and “bad” kinds of ruthlessness when it comes to leadership, and Nero seemed unable to discern the one from the other. He ordered his own mother’s (Agrippina’s) assassination, which caused uneasy grumbling among Rome’s patrician families. But when he had his first wife Octavia, the virtuous daughter of the late Emperor Claudius, also murdered in order to appease his equally repulsive second wife, there was a long and lasting public outcry. Still, in time these crimes might have been overlooked, had it not been for his unbecoming effeminacy and lack of military ambition.

[9]

[9]You can buy Greg Johnson’s From Plato to Postmodernism here [10]

Instead of doing something respectable, like winning a minor campaign against a Teutoni tribe, he went abroad to participate in Hellenic talent shows. While traveling in Greece, he entered 1,800 acting competitions, naturally taking first prize in exactly 1,800 of them.[7] [11] Indeed, Nero subjected anyone who would listen (and who could refuse?) to extended soliloquies and poems accompanied by his lyre-playing. A captive audience member had the effrontery to doze off during one of these sessions, and in order to preempt Nero’s no doubt creative revenge, the poor man committed suicide. So proud of his Grecian achievements was the Emperor that he asked (demanded!) that the Senate approve a triumph for his homecoming — an honor only accorded to those Roman commanders who had led their legions in conquest. As readers can imagine, this did not sit well with the aristocrats of the Senate, most of whom considered Nero’s Broadway tour to be well beneath the dignity of his office. His enfant terrible posture grew less and less tolerable the older he got. According to Greco-Roman historian Seutonius, someone once quoted a familiar line from an unnamed Greek playwright during a casual discussion with the Emperor: “When I am dead, let fire devour the world,” the man recited. And Nero shot back: “No — while I’m alive.”[8] [12] Attempts like these at fostering an edgy, controversial persona would return to haunt him.

Ever since the advent of civilizations and their cities, arson has always been a serious crime (until “Civil Rights,” anyway). But the ancient world took fires especially seriously. Without fire hydrants, hoses, protective gear, or a dedicated force of trained professionals, these cities and their residents had few means of quenching large conflagrations.[9] [13] Sometimes, the only options available to them were fire breaks accomplished by demolishing the structures in the flames’ path, or to simply stand aside and let the fire burn itself out. In the process, entire neighborhoods and towns could go up in smoke. This was a devastating event that not only rendered scores of people homeless and destitute, but left cities in a vulnerable position — a perfect opportunity for an enemy to strike. It also provided a perfect opportunity for one’s internal enemies. Accusing political rivals of arson was an easy way to stoke the angry passions of the people, as Cicero once did when he slurred Catiline, Clodius, and Mark Antony as “incendiaries.” Universally draconian punishments for fire-setting across the ancient world revealed the extent of the terror such blazes excited, and their potential danger to life and property. The famous law code of Hammurabi’s Babylon prescribed death by burning should a man be caught looting during a fire. The later Hittites were harsher still, and those found guilty of causing even accidental fires inside their temples were put to the sword, along with their family members.[10] [14]

The earliest Roman fire codes found to date came from the so-called “Law of the Twelve Tables,” circa mid-fifth century BC. They mandated a minimum of two and a half feet of space between buildings, and if the rite were to take place less than 60 feet from a neighbor’s dwelling, families were required to ask permission when burning their funeral pyres. If a fire happened to damage another’s property through accident or negligence, the perpetrator was bound to pay restitution out-of-pocket; if the damage was deliberate, the arsonist would pay with his life.[11] [15] The image we have of Rome during the age of the Cæsars — a marble city spread across seven hills, shimmering smooth glass by sunray, glimmering cooled white by moonbeam — is an image seen from a distance. Up close, Rome’s urban slums were filled with tightly-packed apartment complexes, built on literal stilts and rising imprudently high above the streets. If a fire began on the bottom floor, the third story of one of these slappity-dash buildings could fill with smoke and ash before residents on the top levels realized that something was amiss. With plenty of flammable material to keep them roaring, flames could spread with alarming speed and in the same winding, unpredictable directions as Rome’s hidden passages and narrow alleyways.

We moderns can sometimes forget the frequency and intensity of flash-fires that roared through urban areas — a hallmark of life during the pre-modern era. Indeed, satirical writer Juvenal once quipped that fires, along with collapsing buildings and “recitations by poets,” were among the worst “horrors” of ancient Rome.[12] [17] It wouldn’t be hyperbolic to describe even the most sophisticated of cities as little more than giant fire-traps set to go ablaze at the first opportunity. Judging from the patchy historical record, Romans seem to have weathered a major fire every 20 years or so.[13] [18] Certainly, the slums and rickety tenements of the Roman poor suffered fire damage more often than aristocratic estates, whose columns crowned the heights on one or other of the city’s fashionable hills — but no place was safe. The Capitoline’s Temple of Jupiter was notoriously susceptible to lightning strikes, for instance, and it burned down at least six times in 100 years. Located in the southwestern corner of the city, between the Aventine and Palatine Hills, the Circus Maximus racetrack was ground zero for scores of fires, including the Great Fire of 64 AD. An alleged act of arson in 210 BC destroyed the Forum Romanum, as well as the home of the chief priest; meanwhile, the nearby Temple of Vesta was only just saved through the heroic efforts of 13 slaves, all of whom were afterwards purchased and freed by the state.

Before the Great Fire under Nero’s aegis, the most traumatic fire Romans had ever experienced was the one that followed in the wake of the Gallic Sack of 390 BC. A Cisalpine tribe had ventured too far into mainland Italy for comfort. So, the Romans marched an army north to confront them, the ensuing battle taking place only miles away from the city. But they underestimated the “barbarians,” who routed them from the field — a defeat that left Rome trembling in her unprotected nakedness. Unable to pass up such a golden opportunity, the Gauls proceeded to seize and plunder the city. Livy recounted that awful day, the nineteenth of July, with a breathless tone. The few lucky Romans who had managed to escape to the high ground atop the Citadel “beheld . . . the enemy” running amok “in all the streets,” while some new disaster “was constantly occurring , . . first in one quarter, then in another.” Wherever these survivors cast their shocked gazes, they saw “the roar of the flames and the crash of houses falling in.” The angry gods had decided to torture their minds as they became helpless “spectators of their country’s fall.”[14] [19]

No sack caused the disaster of 64 AD, a blaze that wrought more destruction than even the Gallic raid had 450 years prior. The fact that it also burst into what would be a nine-day rampage on July the nineteenth escaped no one’s notice. Although it is impossible to be certain, the fire likely started near the Circus Maximus — a long, wooden racetrack in which games, banquets, and festivals took place, and a venue that drew in crowds from all corners of the city. Vendors of every description ran their shops beneath its lower levels and often worked beside open flames. A substantial number of these stalls and their merchants served food, and they required a nearby stovetop to cook their offerings. Wherever it originated, a small fire escaped from containment that evening, took hold, and almost “instantly became so fierce and so rapid from the wind, that it seized in its grasp the entire length of the circus.”[15] [20] Known as the siroccos, hot summer winds woven over the Sahara and blown north into the Mediterranean, they often reached near-hurricane strength speeds, with gusts climbing up to 70 miles per hour. This phenomenon was the probable culprit for the “instant fierceness” that overcame all early efforts to extinguish the problem. An unhappy marriage of flame and gale together bore a roaring firestorm. Like tornadoes, such whirlwinds have a distinctive and horrible voice that can easily steal the voices from their victims’ screaming lungs.

The blaze “in its fury ran first through the level portions of the city, then rising to the hills, while it again devastated every place below them.” As if it were a clever opponent with a mind of its own, the fire “outstripped all preventive measures.” Added to the scene of this hellish inferno “were the wailings of terror-stricken women, the feebleness of old age, the helpless inexperience of childhood,” as some desperately sought sanctuary in a covered, dark, protected space. But most people simply spilled into the streets, the avenues choked not only with smoke, but the frantic press of humanity. When these unfortunates “looked behind them, they were [often] intercepted by flames on their sides or in their faces.” If they thought to reach “a refuge close at hand . . . this too was seized by the fire.” Places where they imagined to be remote, were “involved in the same calamity.” Exhausted, sooty, and struggling for a clean breath of air, they paced half-mad circles in the streets, “or flung themselves down” in despair.[16] [21] And so Old Rome disappeared one night, its remains scattered with the wind that had so violently whipped up its killer. But the fire was still hungry.

It continued to consume the city for another eight days till it finally died, sated with having left Rome a blackened shell and its residents in hollow-eyed shock. There is no way to venture an accurate figure accounting for the casualties. Experts do not even know how many people lived in the city before the Great Fire (it was probably between 500,000 and 1.5 million individuals — quite a wide range). And there were other victims apart from the city’s human inhabitants. Reflecting on the longevity of trees in his masterpiece Natural History, Pliny the Elder wrote about one of his favorite specimens that grew outside his friend Cæcina Largus’ Roman villa. Largus “used often to point them out to me in my younger days,” full, leafy, and vibrant in the prodigious Italian sunshine. Sights like those had nurtured his childhood desire of becoming a student of nature. “They were still in existence,” he continued bitterly, “down to the period when the Emperor Nero set fire to the City.” And there they would be still, “with all the freshness of youth upon them, had not that prince thought fit to hasten the death of the very trees even.”[17] [22] The literal firestorm had ended; the political one had only begun.

Nero, it seemed, had gotten his wish. Indeed, the earth had caught fire while he still lived — and now, all Roman eyes fixed in his direction. Some began grumbling that the Emperor had been conveniently absent at the start of the fire, only coming to his city’s aid when a messenger brought him word that his own enormous mansion was under threat. To his credit, Nero immediately threw himself into clearing the debris and rebuilding Rome anew. But he turned what could have been a unifying experience into a public relations catastrophe. When he called for the raising of taxes in order to begin construction, most Romans understood the necessity. After all, the homeless, widowed, and orphaned survivors needed shelter. To increase the money supply, Nero approved devaluing the currency, and Roman coins were no longer silver but alloy. When people realized, however, that most of these new funds were going to pay for Nero’s massively expensive palace complex to be built atop the ashes of so much lost property, public opinion turned against him for good. Even more galling, he hired famed sculptor Zenodotus to make a “colossus” of himself, a statue more than 100 feet in height, and posing as the Sun god. The phrase “monumental vanity” has rarely had a better historical example. The cost, coming at a time of economic hardship and inflation, was many hundreds of thousands of sesterces. “Detestable,” Pliny groused.[18] [23] The Emperor — champion of the people, protector of the commonweal — was profiting off the misfortunes of ordinary citizens, no better than a common looter. Alas for Nero, if there was something in Rome that had always spread quicker than wildfire, it was rumor.

Stories began circulating that the Emperor had been inside the city at the time the fire started. Not only had he been there, but he had thrown an orgy atop Esquiline Hill, a steep promontory on the eastern edge of the city and one of the few places spared from damage. As the flames engulfed the city below, the party did not break up; it moved outside to watch. So enraptured at the sight of what appeared to be all of Rome combusting into the night sky (and who can deny that fires have a mesmeric, beautiful quality when seen from afar?), Nero grabbed his lyre and began to recite an “original” epic poem about the fall of Troy. For the amateur thespian, the Great Fire was the Greatest of Muses — and the narrative only got nastier. The leap from suspecting Nero of tone-deaf callousness to malicious complicity was not a long one, for some began to believe that burning down the city had been his plan all along. Though the charges were almost certainly untrue, as they have for countless cases throughout history, Big Lies proved to be the more appealing.

[25]

[25]You can buy Collin Cleary’s Summoning the Gods here [26].

Nero realized the ugliness of Rome’s mood, the resentment that hovered like a pall over the capital. So, he attempted a classic (and logical) escape through finger-pointing. To dispel the gossip about his personal guilt, “Nero therefore contrived culprits on whom he inflicted the most exotic punishments.”[19] [27] The handful of Christians living in Rome were universally loathed — more despised than the Jews (because even the Jews hated them). Once thought suppressed during the reign of Tiberius, this new religious group “broke out again” from Judea and Greece — and “Rome as well,” Tacitus wrote acidly, “where all that is abominable and shameful in the world flows together and gains popularity.” In other words: They were the perfect scapegoats. After torturing a “confession” from a few of their number, Nero accused all of them of arson, of having started the blaze, and the state sentenced them to death. As they died, “they were further subjected to insult. Covered with hides of wild beasts, they perished by being torn to pieces by dogs” — or, in mockery of the Messiah, “they would be fastened to crosses, and when the daylight had gone, set on fire to provide street-lighting” at night.[20] [28]

But his plan backfired fantastically. Not only did suspicions against him remain strong, but his cruelty toward this unpopular minority won for them what they could never have won by themselves: (grudging) sympathy. Along with this shift in perception, Christians now had a powerful story of martyrdom to wield in which they could tell how they took their stand deep in the belly of “the Beast”; in which they proved their faith by defying the Whore of Babylon on her own territory. Nero’s image continued its tailspin, until in 68 BC — four years after the Great Fire — he was friendless and abandoned by his own Praetorian Guard.[21] [29] The Senate declared him a renegade and an infamous arsonist. Nero then fled to a villa outside Rome, where he performed the most dramatic act of his theatrical career: He plunged a dagger into his throat and felled the Julio-Claudian dynasty. The Imperial title would ever after be open to all challengers, regardless of descent, regardless of the instability every ambitious general at the head of a legionary army could cause. Nero himself would remain the worst tyrant in the Western imagination until the twentieth century’s superior examples. The words set in the kind of stone that would outlast all of Nero’s own marble projects was the charge: “Nero fiddled while Rome burned.” A dark prophecy from certain Christian communities foretold that another Nero would be woken by a convulsion underground and rise out of a crevice in the Italian earth. A fire will escape and reach wide heaven, And will burn many towns and kill men, And when many glowing ashes will fill the large heaven And drops will fall out of heaven like blood, Then know that it is the scorn of God . . . Since they will ruin the people of guiltless piety.[22] [30]

A prescient forecast. The world was a more interesting place, readers, when dreams meant more than repressed psychosexual desires, and curses showed more effort than ugly, profanity-laced tirades on Twitter. Yes, Pliny thought as he felt a familiar, short-lived tremor rocking him on the unsteady Campania ground, “the fires of the emperor Nero” proved that singular events — that turning points, too — had the power to shake the earth and sweep an emperor off his feet.

Daylight Came Three Days Later

No one had suspected that old Vesuvius was a monster.

Shaking his head in an amazement hardly lessened over the 20 years that had since passed, Pliny the Younger (henceforth “Gaius Pliny,” or “Gaius”) wrote to his friend: “My dear Tacitus, you ask me to tell you something about the death of my uncle so that the account you transmit to posterity is as reliable as possible.”[23] [31] For the sake of his beloved relative’s reputation, Gaius Pliny had resolved to conjure from memory those terrible past images and make them vivid again. Two decades before Gaius sat down with pen, ink, and sheaf of paper, his uncle Pliny the Elder marveled at his last natural wonder. It was the time following the “Year of Four Emperors”; after Nero’s suicide left no suitable heir from his house, several generals vied for the title pinceps, plunging Rome into civil war. The victor Vespasian was a man of humble origins — a “mule breeder,” as his opponents mocked him. But this duel between men was a petty drama compared to the fire that consumed the Campania region around the city of Naples,[24] [32] more catastrophic even than the Great Fire of 64. And it couldn’t have happened in a more beautiful setting.

The rises of Mount Vesuvius were covered in trees, twining thorn-brush, and vineyards during the summer of 79 AD. Since the early Bronze Age, the mountain had slumbered and nourished the meadows near its peaceful slopes, a benign figure. The summit had even provided refuge for rebel slaves under Spartacus’ leadership in 73 BC. At the time, the inner caldera looked like “a vast shell, 1,500 meters across with steep rocks and tangled with nettles,” its thick woods infested with wild boars rooting in the thickets.[25] [33] Researchers still debate the angle and height of its ancient steepness, and some claim that Roman wall frescoes purportedly illustrating Vesuvius suggest that in those days, it had the shape of a tall cone. Others argue that it was more of a prominent mound — the “decapitated” remnant of a much older volcano, and one geologists now call Somma-Vesuvius; the Vesuvius of our own era had yet to appear.[26] [34]

[35]

[35]A famous Herculaneum fresco of Bacchus at the foot of Vesuvius, showing the mountain to be quite steep and lush

However it looked 2,000 years ago, area residents regarded the mountain with affection. Only a few scholars recognized Vesuvius for what it once was. It dominated the area for many miles in all directions, a Greek geographer noted of the Neapolitan landscape in 15 AD, “which is covered in fine fields except on [the mountain’s] crest.” Inside the flat summit “it is unfruitful, and ash-colored. Its rocks are [sooty], with holes in them like pores,” and looking as if they had been “eaten by primal fires.”[27] [36] As for Pliny the Elder and his famed Natural History, his lengthy list of known volcanoes ironically failed to mention the most dangerous one in Europe, even as it cast its long shadow over the lush pastures and becks where he had lived for many years. It was too familiar a presence — a neighbor Pliny would have seen every day — for him to believe that a mysterious fire demon, more ancient than the gods, lay coiled inside.

By the mid-first century AD, Campania was densely settled and wealthy — a favored spot where rich Romans vacationed or retired. As the hub city of that district, Naples had a population of perhaps 50,000; Capua, Nola, and Pompeii served as its bustling suburban market towns; Herculaneum and Misenum were resorts of 5-6,000 people to the northwest.[28] [37] After the Great Fire of 64, some of them might have moved permanently from the capital to these Campania villages by the seaside, having had enough of Rome’s constant melodrama. Yes, there were earthquakes that occasionally damaged a roof, or wall. But Campanians were used to these inconveniences; they had learned to wait them out with a practical, if not cheerful acceptance. The danger seldom lasted for long, and always passed. Life and business usually resumed their normal courses as if nothing had disturbed them.[29] [38]

The 24th of August[30] [39] seemed like another unremarkable, pretty summer day in the town of Misenum. Pliny was staying with his sister and her 17-year-old son, Gaius Pliny, and enjoying the fresh air. That morning he “had taken a turn in the sun and, after bathing in some cold water and making a light luncheon, had returned to his books.” At one in the afternoon, he heard a brief commotion. Gaius’ mother pulled Gaius and his uncle outside to observe a strange cloud gathering in the east. Pliny immediately hiked to a spot of high ground “from whence he might get a better sight of this uncommon appearance,” but from their vantage none could tell from which mountain the unusual shape billowed. “I cannot give you a more exact description of” the ascending cloud, Gaius admitted, “than by likening it to that of a pine tree, for it shot up to a great height in the form of a very tall trunk, which spread itself out at the top into a sort of branches.” At times it appeared “bright and at others dark and spotted,” depending on whether it “was more or less filled with earth and cinders.”[31] [40]

The naturalist in his uncle was giddy, and he determined to ready a light vessel so that he and a small crew could sail east along the coast and further investigate the phenomenon. But as Pliny was leaving the house, a breathless messenger arrived with a note from a female friend named Rectina. She “was in the utmost alarm at the imminent danger which threatened her, for her villa lay at the foot of Mount Vesuvius, and there was no way for her to escape, but by sea.” Thus, she begged him to come to her aid. Pliny’s intention changed from scientific philosopher to a noble Roman admiral whose duty it was to rescue her and others trapped in towns “thickly strewn along that beautiful coast.”[32] [41] In a flash it was clear that Vesuvius, she had awakened.

Though Gaius was tempted to follow the uncle he so admired, he could not leave his aging mother behind, so he watched as Pliny lifted anchor and sailed away. And as the admiral steered his course toward “that dreadful scene,” he eventually came so close to the mountain “that cinders, which grew thicker and hotter the nearer he approached, fell into the ships, together with pumice stones and black pieces of burning rock.”[33] [42] The men tied pillows around their heads with napkins, their only defense against the storm of stones that fell and gathered in droves around them. Sometimes they glowed and hissed as they hit the surface of a roiling sea and plunged toward the bottom.

Though it was day everywhere else in Rome’s vast Mediterranean empire, near the mountain a “deeper darkness prevailed than in the thickest night,” for it was night “not such as [one sees] when the sky is cloudy, or when there is no moon.”[34] [43] But it was night like a close, windowless room when it is shut up and all the candles extinguished. Even after the true night arrived, the horror continued. Broad flames “shone out in several places” from Vesuvius, which the darkness rendered still brighter and clearer. Gaius and his mother had meanwhile fled their house on foot, looking back often at the black and dreadful cloud, its plumes “broken with rapid, zig-zag flashes and revealing behind it . . . masses of flame like sheet-lightning.” Gaius recalled his fearlessness in the face of Armageddon, but it was not real bravery, he confessed. It was instead “that miserable, though mighty, consolation, that all mankind were involved in the same calamity, and that [he] was perishing with the world itself.”[35] [44]

The Elder Pliny also maintained an equanimity borne of sea battles and a long life filled with near-misses and escapes. The Roman perfected the “stiff upper lip” long before the Britisher wore it. But, as our Weather Channel hurricane reporters are fond of screaming into the horizontal wind, by midnight the situation had deteriorated. Having rescued a number of panicked civilians, Pliny and his crew attempted to hug the shoreline “to see if they might safely put out to sea,” but found the waves “running too high and boisterous.” It was becoming a struggle simply to breathe. Gasping, Pliny “lay down upon a sailing cloth . . . and called twice for cold water.” His servants helped him to sit and placed the cup at his parched and blackened lips. But before he could take a full draught, sudden flames, “preceded by a strong whiff of sulphur,” flattened the group around him. At last, and after a front-row show at the scene of the most dramatic natural disaster of the ancient world, the greatest ancient naturalist “fell down dead” of suffocation.[36] [45]

[47]

[47]You can buy North American New Right vol. 2 here [48]

There were many fortunate souls who, like Gauis and his mother, survived the Vesuvius eruption. Even those from Pompeii and other settlements close to the volcano’s foothills had a window of time in which to flee. But thousands of others died in the manner of old Pliny: suffocated or burned to death by several unsurvivable pyroclastic flows that buffeted and buried places like Pompeii and Herculaneum in searing ashy avalanches traveling at perhaps more than 200 miles per hour. As it is difficult to give an estimate of the number of people lost to Rome’s Great Fire, so it is also difficult to guess the death toll exacted by Vesuvius. We only know that wherever archeologists continue to dig in the areas surrounding these ruined towns, they discover more bones. Based on the skeletal remains found in Herculaneum, the flows consumed anyone left behind in a pumice hurricane, its gasses heated to nearly 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit. The men seemed to have mostly died on the town’s beaches, while women and children — sheltering nearby — died in the boat houses and at the same instant as their men.[37] [49] There they would every one remain undisturbed for many centuries, still waiting only yards from the sea for a ship and their deliverance.

“After three days,” Gaius remembered, “[the] dreadful darkness was dissipated by degrees . . . and the real day returned.” Even the Sun came out, “though with a lurid light, like when an eclipse is coming on.” Every object that meanwhile greeted their weakened eyes “seemed changed, being covered deep with ashes as if with snow.”[38] [50] So profoundly were Pompeii and Herculaneum buried under a blanket of the stuff that they would remain uninhabited for a millennium, and because of this, when the interred cities were suddenly rediscovered in the eighteenth century, researchers found a complete cross-section of Roman society, preserved like no other ancient site on Earth, down to the finest of details. And it was the revelation of these sites that first established the professional science of archeology as we know it today. Vesuvius, meanwhile, was no more the friendly neighbor, but she had become the black goddess of Italy; the feared and admired patroness of Naples whom she held in an imperium more mythically powerful than any Roman emperor before or after her.

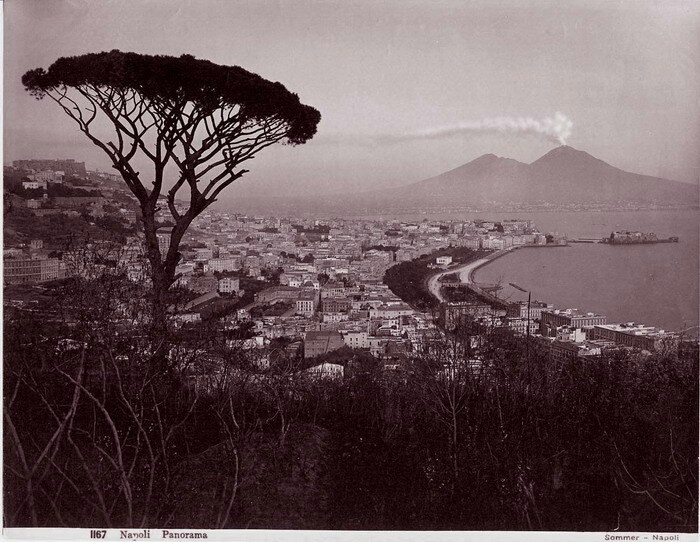

[51]

[51]Giorgio Sommer’s photograph of Vesuvius from a vantage overlooking Naples, with a pine tree in the foreground, ca. 1900

Sepulchers of Cities

“Let us say no more of earthquakes and of whatever else may be regarded as the sepulchres of cities,” the Elder Pliny once pleaded. Let us “rather speak of the wonders of the earth than of the crimes of nature.”[39] [52] On whatever plane his spirit now wanders, I cannot help but think that he is gratified to have fallen not to another man’s blow, but to one of the most spectacular “wonders of the earth,” and that his death was, in his mind, no crime. Pliny was a martyr to his scholarly passion in a quest no less noble than the passion of Nero’s Christians martyred for their God. These were the two most sensational fires of Western history, and ones that continue to burn in the popular imagination.

Save for the literary icons of Homer, no characters nor places like those of the ancient Roman Empire have exerted such a mighty psychological pull over western Europe and North America. Europeans have attached a special romance to ruins: jagged columns, tragedies, and doomed causes. Fragments of things allow our imaginations the freedom to roam. To wonder at the power of myth during times of natural or manmade disasters that can easily make sepulchres our finest cities. A creative tension exists between the aesthetically compelling shards before us and the vision of the monuments they once supported. The “fall of Rome” has haunted us like no other narrative, her collapse simultaneously giving rise to many high towers of myth and legend. In our collective memory, the two “great fires” of first-century Rome were dramatic rehearsals of her final decline, a time when the world was aflame, and the gods, they had finally abandoned her. As the palisades of Rome and the center of the mountain collapsed atop their own heaving conflagrations, they too became towering legends. Vesuvius, once a “decapitated” crater quietly suffering human encroachment onto her slopes, even now rises higher into the air as a menacing icon demanding the vigilance of her subjects. It is only a matter of time before she erupts again.[40] [53] The golden reign of a God-Emperor fell to pieces in what became his funeral pyre, transforming him into a black legend for all time — even perhaps into the devil himself. These are the only “black gods” Rome should ever know.

It is sometimes an uncomfortable kind of awareness when we realize that many of our oldest Western cities stand atop the (sometimes literal) graveyards of earlier versions of themselves — just as Vesuvius is the latest mountain cratered over the same deep pool of magma, hundreds of thousands (maybe millions) of years old.[41] [54] Indeed, it’s an almost spiritual experience to walk in an ancient city. If attuned to such things, one recognizes that he is a kind of time traveler. Look closely, and see the vertical chronological layering of not one Rome, but a superimposed many Romes. And in the abstract realm of ideas, too, Rome exists as many variations of itself — its history, myths, emperors, and debacles — as a shape-shifter that adapts with every age, though still fixed, in many ways, as a foundation stone of Western civilization. Modern Rome throbs with life on its bustling streets, while Herculaneum and old Pompeii are ghost towns, but both the Neronian and Vesuvian fires froze in petrified ash the mute expressions of a generation’s last amber-golden, and then terrible hours that nevertheless speak a sort of silent eloquence understood by all the ages.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[56]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[56]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.

Notes

[1] [57] In order, and beginning with the “founder” of the dynasty (even if he was not technically an emperor), these Julio-Claudians were: Julius Cæsar (45 BC -44), Octavian “Augustus (31 BC-14 AD),” Tiberius (13-37), Caligula (37-41), Claudius (41-54), and Nero (54-68); after this house, the Flavian Dynasty assumed the Imperial aegis. Of these six rulers, only Augustus and Tiberius died of natural causes (and even their causes of death are disputed).

[2] [58] Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 2.4, “Of the Elements and the Planets” in Perseus Classics Collection [59]. This is the largest single-authored text collection to have survived from the Roman Empire to the present day; a portion was published in 77 AD, and the rest posthumously by his nephew Pliny the Younger after the Elder’s death in 79 AD.

[3] [60] Natural History, Book 2.27, “Of the Colours of the Sky and Celestial Flame.”

[4] [61] Natural History, Book 2.23, “Of Comets, Their Nature, Situation, and Species.”

[5] [62] Ibid.

[6] [63] Natural History, Book 2.110, “Places Which Are Always Burning.”

[7] [64] I have a difficult time believing that he entered so many contests, but whether or not the figure was accurate, its huge number, even keeping in mind the Classical era’s love of public speaking, seems to suggest an obsessive predilection for public exhibitionism — particularly for his office.

[8] [65] Seutonius, Lives of the Cæsars, “Nero,” Chapter 38 [66], Perseus Classics Collection. Originally published ca. 115 AD.

[9] [67] For a while, Rome had a quasi-organized police force known as the vigiles (watchmen), whose duties included fire-fighting.

[10] [68] See Anthony A. Barrett’s Rome is Burning: Nero and the Fire that Ended a Dynasty (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2020), 27-28.

[11] [69] Ibid., 29-30.

[12] [70] Juvenal, Satires, Satire 3.7–9 [71]. Originally written ca. 115 AD.

[13] [72] See Rome is Burning, 47.

[14] [73] Livy, The History of Rome, Book 5.42 [74] in Perseus Classics Collection. Originally written ca. 15 BC.

[15] [75] Tacitus, The Annals, Book 15, The Internet Classics Archive [76]. Written ca. 116 AD.

[16] [77] Ibid.

[17] [78] Natural History, Book 17.1, “Trees Which Have Been Sold at Enormous Prices.”

[18] [79] Natural History, Book 34.18, “The Most Celebrated Colossal Statues in the City.”

[19] [80] Tacitus, The Annals.

[20] [81] Ibid.

[21] [82] Not that this group was known for its fidelity.

[22] [83] See Eric M. Moorman, Pompeii’s Ashes: The Reception of the Cities Buried by Vesuvius in Literature, Music, and Drama (Boston: Walter de Gruyter, Inc., 2015), 9.

[23] [84] Pliny the Younger, Letters of Pliny, Letter 65, “Letter to Cornelius Tacitus [85].” Written ca. 100 AD.

[24] [86] Naples was referred to as “Neapolis” at this time.

[25] [87]See Alwyn Scarth, Vesuvius: A Biography (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2009), 36.

[26] [88]Ibid., 12.

[27] [89] Pompeii’s Ashes, 17.

[28] [90] See Scarth’s Vesuvius, 39.

[29] [91] A major exception being the damaging Campania Earthquake of 62/63 AD, a precursor to the eruption in 79.

[30] [92] Most past and current scholarship has arrived at this late summer date, but there are some modern researchers who have suggested that the eruption may have actually happened sometime in the fall.

[31] [93] Letters of Pliny, Letter 65.

[32] [94] Ibid.

[33] [95] Ibid.

[34] [96] Letters of Pliny, Letter 66, “Letter to Cornelius Tacitus.”

[35] [97] Ibid.

[36] [98] Letters of Pliny, Letter 65, “Letter to Cornelius Tacitus.”

[37] [99] See Ernesto De Carolis and Giovanni Patricelli, Vesuvius A.D. 79: The Destruction of Pompeii and Herculaneum (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2003), 96.

[38] [100] Letters of Pliny, Letter 66.

[39] [101] Natural History, Book 2.95, “Of Vents in the Earth.”

[40] [102] Vesuvius has erupted perhaps over forty times since 79 AD, though these events have varied significantly in severity — and none were as catastrophic as the 79 eruption. The volcano has been quiet since 1944.

[41] [103] Like all Italian volcanoes and earthquakes, Vesuvius exists because the continental plate of Africa is colliding with Europe. I recommend this time-lapse video [104]of the 79 AD Vesuvian eruption from the vantage of Pompeii.