The Mark of Caine: Get Carter

Posted By Mark Gullick On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled“Hey, Ma! Look at my shoes! Aren’t they great?”

“Oh my God! You look like a gangster.”

— Goodfellas

Gangster movies, like war films and Westerns, are not simply a part of the American cinematic tradition, but a component in the collective psyche of its people. The well-dressed gentleman rogue who sees violence as a necessary part of business, and business as essentially a family or quasi-familial operation, is iconic. Crime, business, and family (or surrogate family) are intertwined. Cosa nostra means “our thing.” So, what makes a good gangster movie?

First of all, in true philosophical style, we must define our terms. What is a gangster? I recently watched a YouTube video billed as the “top ten British gangster movies” and, although there were some great films in there, they were not all gangster movies. In Bruges is a brilliant comedy noir starring the supreme British (mostly Irish) acting triumvirate of Colin Farrell, Brendan Gleeson, and Ralph Fiennes, but it is not a gangster film. There is no gang. Farrell and Gleeson are hit men in hiding, and Fiennes is a particularly nasty villain. Sexy Beast is another excellent British film featuring a staggering Oscar-nominated performance by Ben Kingsley as Don Logan — watch him respond to an air stewardess who objects to him smoking on an airplane [2] — but there are no gangsters. Logan is putting a team together for a bank heist. Hit-man and heist movies are not gangster movies other than incidentally.

The Godfather movies were gangster movies, Pulp Fiction was not. Lawless is more of a gangster movie than Reservoir Dogs. A gangster movie needs the family, the mob, the pack, to bring out the most primal behavior in bad guys. Oh, and good suits don’t do any harm, as we shall see when we turn to the mafia’s influence on British gangsters.

The first gangster movie I can remember seeing was Angels with Dirty Faces. Cagney plays a tough-guy mobster who also has a soft spot for a boys’ club run by a priest he knew as a kid. I usually hate to Google (it’s a prosthetic memory which weakens the real thing, like spectacles weaken your unaided vision), but I couldn’t remember the actor who played the priest. He was great, and Big Tech tells me he was played by Irishman Pat O’Brien. It is a phenomenal movie — Bogart is also in it — with one of the best payoffs ever. I won’t spoil.

Martin Scorsese, a genuine American national treasure, made two of the most famous gangster movies in Goodfellas and Casino, both accurate renderings of books by ex-mobster Nick Pileggi, who co-wrote the scripts. Goodfellas shows the mob in action (a much more downbeat portrayal of quotidian life in the mafia would later appear in Donnie Brasco), whereas Casino shows the mob’s financial reach and how they protect their investments.

And money is central to the gangster movie. In the heist or hit-man movie, it is a one-off payment; fireworks money. In the gangster movie it is the oil that greases the family economy, and it needs to be consistent. As Joe Pesci’s character Nicky Santoro says in Casino, “Whaddya think we’re doin’ out here in the desert?” In the same movie, when Frank Marino goes back to the bosses with ever-decreasing bags of skimmed cash from Vegas, he finally says, “I didn’t know if I was gonna be kissed or killed.”

It is amusing to note that, even though to be “made” by the mafia you had to have family lineage going back to the old country, the cosa nostra were more realistic when it came to accountancy. Meyer Lansky, the Polish Jew widely credited as the financial brains behind Lucky Luciano’s mafia (Lansky is Hyman Roth in The Godfather), was the subject of a gag by Jewish comedian Jackie Mason:

All those Italians with broad shoulders and dark glasses? How could they possibly have created something like the mafia — unless they had a Jew to show them how? Meyer Lansky? He’s their Henry Kissinger.

So, from black-and-white, Valentine’s Day massacre wiseguys with their Tommy-guns in violin cases to The Sopranos with their bad shirts and their automatic pistols, both moviemakers and the American public have a long-standing love affair with the bad guy in the sharp suit.

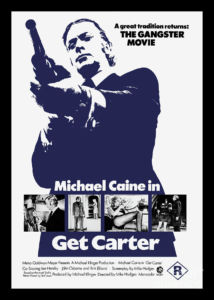

As for the film industry in my country, I am not certain which of two English gangster movies I saw first. Brighton Rock was certainly made first. I lived in Brighton for many years and drank in a couple of the original pubs used in the film, in which national treasure Sir Richard “Dicky” Attenborough plays novelist Grahame Greene’s doomed chancer, Pinky. The British refer to actors as “luvvies,” and Attenborough — brother of the famous naturalist Sir David — is the original. Brighton Rock is a great atmospheric period movie, but the British gangster movie that changed everything for me was 1971’s Get Carter.

Based on a tough pulp novel called Jack’s Return Home by Ted Lewis (if you like the movie, read the book), Get Carter is based in and around Newcastle. For those of you unfamiliar with England’s geography, there is a semi-jocular saying that “It’s grim up north,” and Newcastle is on a short-list of the grimmest. I know. I’ve been there. The city is a minor character in Get Carter, however, like Manhattan in Woody Allen’s film of the same name, Bruges in In Bruges, or Paris in any film set in Paris.

Michael Caine plays Jack Carter, a suave London gangster returning to his hometown of Newcastle to find out how his brother died in mysterious circumstances. Critics of the film have noted that Caine has no discernible Geordie accent — it being the most impenetrable British accent this side of Glasgow — but talks, well, like Michael Caine. Caine is probably the most vocally imitated British actor, and any British impersonator can do Caine the same way their American counterparts can do Pacino. Amusingly, as the film unfolds, we note that just about nobody in it has a Geordie accent. Perhaps the producers shied at the extra cost of subtitling.

Carter’s London bosses are not keen on the trip, and the stakes are high. He is having an affair with the girlfriend — played by the sultry Swedish actress Britt Ekland, who famously married Peter Sellers — of the gang boss, who has to have been cast because of his resemblance to London gangster Ronny Kray, of whom more later. Jack goes anyway, travelling north on a train in an opening sequence brought to life by Roy Budd’s fabulous jazz-Latin musical score. The sharply-suited Caine relaxes in his seat, engrossed in a book, which happens to be Farewell My Lovely by Raymond Chandler, more gumshoe than gangster, but alerting us to the fact that Jack is going home to do some sleuthing, and also something else. He has left the gang behind. He has risked pack rejection, death to any wild animal.

The connection between the gangster and the pack is a strong one. Al Pacino’s character Carlito Brigante in Carlito’s Way is trying to get out of the gangster life and go straight, but he instinctively reverts to type when he has a disagreement with a wannabe gangster and tells him:

You think you like me? You ain’t like me, motherfucker. You a punk. I been with made people, connected people. Who you been with? Chain-snatching, jive-ass, maricon [NB. Latino Spanish slang for “faggot”; don’t say it to a Latino unless you wish to be knifed] motherfuckers. Go on, go snatch a purse.

[3]

[3]You can buy Mark Gullick’s Vanikin in the Underworld here. [4]

There is a class system even in the underworld.

As Carter delves further into who killed his brother, he discovers a murky world of underground pornography, and this aspect of Get Carter shows the difference between 1970s culture and today’s just as much as the period cars, flared trousers, and the fact that everyone is smoking all the time.

Nowadays, pornography is available in high resolution within a mouse-click, and can be shot on a phone. When Get Carter was made, what were rather coyly called “blue movies” had to be produced, at high material cost, shot on celluloid, and shown on ratchetty film projectors in dark basements of seedy clubs in Soho. Oh, and it was highly illegal, a fact which provides Carter with both motive and means in the film. There is a scene in which Carter recognizes a loved one in one of these films, and his quiet grief and tears are moving. Then he gets back to his day job of violence and intimidation.

Caine plays what he is supposed to play, a man described by another character as a “tough nut.” Carter watches dispassionately as a sports car submerges in a canal, knowing that in the trunk is a woman — still alive — with whom he was in bed an hour previously. Caine has the ability to make his eyes go dead. Walken and Pacino have the same acting knack.

Get Carter is a blueprint rogue gangster movie. There is a similar sub-theme in Donald Cammell and Nic Roeg’s 1970 film Performance, in which James Fox plays a London hard man who crosses the gang and ends up holing up with faded pop star Turner, famously played by Mick Jagger. In passing, and for genuine film buffs (I am just a pretend one, although I did start out in magazines as a film reviewer), Nic Roeg managed the extraordinary feat of perfectly casting musicians who were quite bad actors by virtue of the fact that each of the characters they played was supposed to be nervous and on edge. All three films repay inspection: Jagger in Performance, Bowie in The Man Who Fell to Earth, and Art Garfunkel in Bad Timing, one of those rare films which lives up to its blurb: “A terrifying love story.” Do not watch Bad Timing with your partner.

But there still remains the questions of the suits. London’s most famous gangsters, the Kray twins, were famously well-dressed, taking the cut of their cloth both from the corporate world and the mob (and the slice of the Venn diagram where those two worlds overlap). Carter is what we Londoners would call dapper, and that comes from a very definite source in the London underworld’s mythology.

Ronnie and Reggie Kray were London’s most notorious gangsters. Cinematically, avoid The Krays, which features the Kemp brothers from the English 1980s band Spandau Ballet, and they are far too pretty for the role. A better bet is Legend, in which the talented Tom Hardy plays both twins, just as Jeremy Irons played twin brothers in 1988’s Dead Ringers. How, as they say, do they do that? To my embarrassment, watching Legend on an 11-hour flight, I recognized Hardy as Reggie Kray, but did not realize he was also playing Ronnie. Every Londoner of my generation has their Kray twins story, and mine is that I once answered my mother’s boyfriend’s telephone to Charlie Kray, the twins’ elder brother. Don’t ask.

But Caine as Carter cemented that actor’s status in England, along with Zulu, Alfie, and iconic heist movie The Italian Job. If you see an Englishman over 50 years old and address him thus, he will know exactly what you mean: “You were only supposed to blow the bloody doors off!” Get Carter was remade in Hollywood with Sylvester Stallone, and to make a full declaration I haven’t seen it. I watched the trailer and felt, essentially, that one should shake one’s head sadly and pass on.

The current incumbents of the back of British bank notes are Churchill, Jane Austen, Turner, and Alan Turing, who was put there as a gesture to the “gay community” after Gordon Brown apologized posthumously to the philosopher who masterminded the code-breaking Enigma machine which helped win the Second World War over his hounding as a homosexual, a woke gesture avant la lettre.

There will undoubtedly be pressure to replace these white devils with some black nurses or bus drivers, but in a truly equitable world Michael Caine would be on the £50 note. He is as close as you can get to a national institution, at least to ordinary people of a certain age. The media are not so sure, however, as Caine is famously conservative.

As with all famous actors, there are apocryphal stories, and there are two concerning Caine I hope are true. Filming in the aforementioned Soho (still known as the seediest part of London), possibly during one of the so-called “Harry Palmer” films (The Ipcress File, Funeral in Berlin, and others), Caine used a break to go and look at a Rolls-Royce showroom, already being a rich man. He asked a car salesman how much a particular model would cost and the man replied, rather more than sir can afford. Incensed, Caine took a taxi to another showroom and bought the same model on the spot. He then drove it around the block past the first dealership, sticking two fingers up at the salesman who snubbed him on each circuit.

Then there was the time Caine was filming in East Berlin — that has to be Funeral in Berlin — and took a bus to explore the city on a rest day from filming. He asked the driver the fare, and was told that it was the same rate for anyone to go anywhere, and that this was a testament to the wonders of Communism. No, explained Caine, it’s because no fucker wants to go anywhere.

So, if you have not had the pleasure of Get Carter, treat yourself. If you enjoy, go after The Long Good Friday next, with the unlikely couple Bob Hoskins and Helen Mirren taking on the IRA. The British gangster movie probably spawned the adjective “gritty.” Gangs will become stronger and figure more in Western urban life as the economy drags and society crumbles. You might as well watch gangsters who have at least some fashion sense. Get Carter is as English as roast beef and potatoes, black taxis, and low-quality dental care.

What is the future of gangs? In the short term, I would say good. I have followed with interest the concerted wave of black looting in the Bay Area of San Francisco and, since Black Friday, more or less nationwide. In the Bay Area, it escalated from some corn-rowed kid and his cousin scooping up trainers to larger groups of feral blacks gutting a store to a 25-car operation which sealed an area and allowed 80 looters to operate unimpeded, even if there were any cops left in San Fran to impede them — and black Democrat mayors, sympathetic white district attorneys, and police chiefs have largely seen to it that there aren’t. Now, what happens when these platoons need marshalling? Blacks won’t organize this kind of thing themselves because they can’t. They will still need whitey, as they do for everything else.

There is a great scene in a great gangster movie, Abel Ferrara’s King of New York, in which Christopher Walken’s character, Frank White, is smooching with his lawyer girlfriend on the subway. Three bad black dudes enter the carriage and ask for his wallet and watch. He pulls back his jacket to reveal a holstered gun and the punks back off. He pulls out a banded wad of notes and throws it to the blacks.

“Come to the Plaza Hotel. Ask for Frank White. I have work for you.”

How long before that scene is prophetic? As White says to the police officer tasked with bringing him down: “I’m not your problem. I’m just a businessman.”

When the feral blacks of the Bay Area get a capo di tutti capi, then the bosses can go back to the stores and say, hey, we see you had a little problem here. Nice place, too. Maybe we could make that go away. Protectionism: the cosa nostra’s business model. The gangster is like the cockroach, breeding and thriving during times both good and bad.

As for movies, I can watch the same one over and over again. I must have seen Get Carter 10 or 12 times. Well, you wouldn’t buy an album, play it once, and never play it again, am I right? In fact, an old girlfriend once said to me, as I was settling down in front of the TV with a famous gangster movie playing yet again, that she found it funny that I could watch the same film so many times.

I simply replied, funny how?

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[5]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[5]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.