Santa Claus, Man of the Right

Posted By William de Vere On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledAn interesting incident [2] occurred in Sicily recently: A Roman Catholic bishop was accused of telling a group of schoolchildren Santa Claus does not exist. The Church has since apologized for these remarks, explaining to outraged parents that the cleric’s intention was direct children away from the consumerism of contemporary Christmas celebrations and towards veneration of the historic Saint Nicholas. This incident provides an opportunity to reflect on the figure of Santa Claus, how he emerged in Northern European and Anglo-American history, and his role in contemporary Christmas festivities.

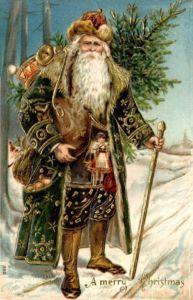

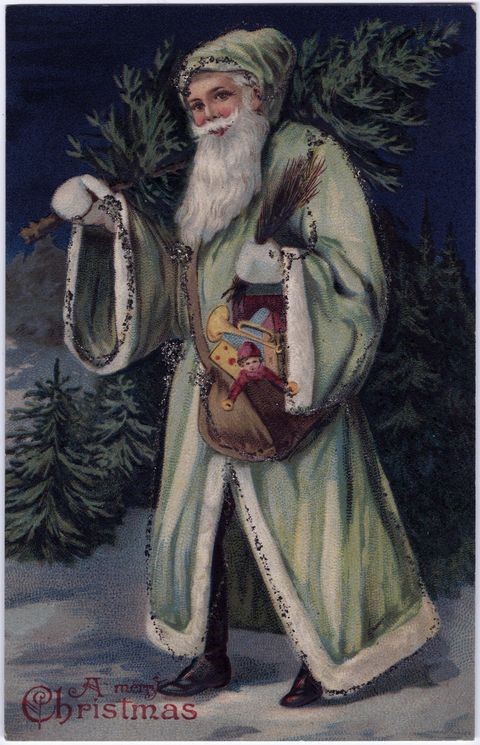

Santa Claus is, in fact, one of the most complex characters in all European legend, his contemporary persona shaped by numerous influences ancient and modern. Let us put aside, for a moment, the latter-day accretions on this myth: the red-and-white suit, the gelatinous belly, the eight tiny reindeer, the maligned but faithful Rudolph, and the fondness for cocaine-infused soft drinks. As the good bishop pointed out to his flock, these are the latter-day inventions of Clement C. Moore [3], Thomas Nast [4], Robert May [5], and Coca-Cola [6]; and while they are an essential part of the contemporary image of Santa Claus, they do not concern us yet. What this essay aims to establish is that the character of Santa Claus has been, since his inception deep in the European past, a defender of traditional order and virtue, and that these characteristics have persisted — in an admittedly adulterated form — into the present.

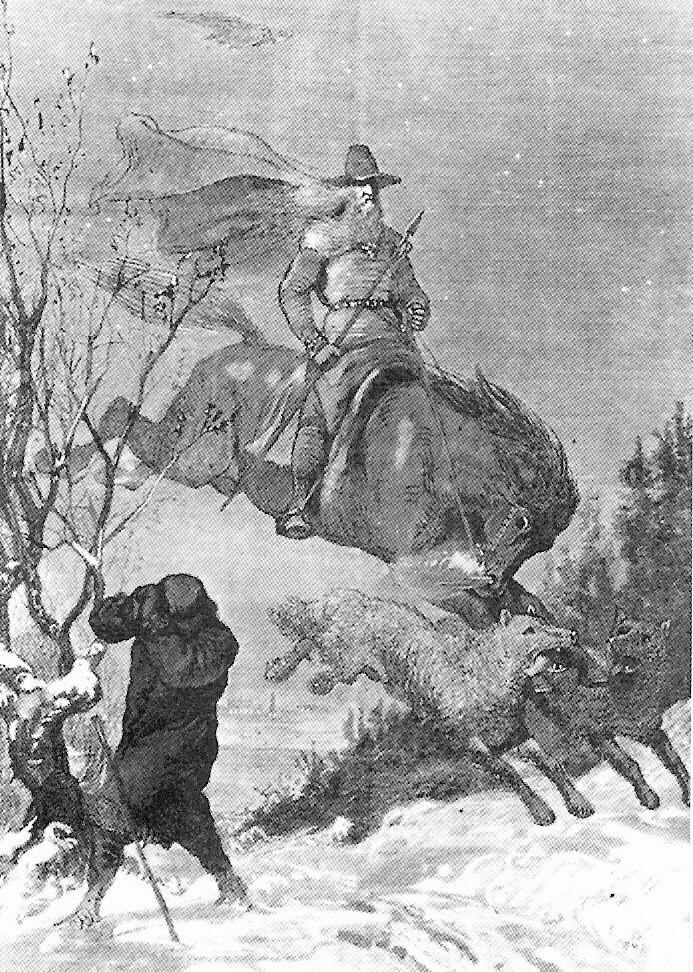

We’ll begin at the origins. This is not to be found, as one might expect, in the third century Greek Saint Nicholas, but in a far more ancient figure: Odin, the Norse god of wisdom, poetry, and war. During the season of Yule, the ancient Northmen believed, Odin could sometimes be seen astride his eight-legged steed, Sleipnir, leading his band of warriors in the Wild Hunt across the winter sky. Despite the sinister connotations of this legend — some who encountered the Wild Hunt were said to be swept away or cursed — other accounts state that Odin would drop gifts at the foot of his sacred pine for the faithful. This gift-giving figure flying through the winter sky on an eight-legged horse is one likely origin of the Santa legend.

Another folk belief held that Odin wandered among his faithful at the time of Yule, disguised in a long, blue, hooded cloak, to observe them around the fireside and leave gifts to those in need. Over time, Odin’s gift-giving qualities increased, and children began putting their boots filled with straw, carrots, or sugar near the fireplace for Sleipnir during his midnight rides; in return, Odin would reward these children by replacing the horse treats with gifts and candy.

[8]

[8]You can buy Collin Cleary’s Summoning the Gods here [9].

Here, at the beginning of the Santa Claus legend, we find a figure who unabashedly embodies the kingly qualities of generosity and martial valor. A monarch, beloved of his people, the gift-bearing Odin is an undoubted paragon of traditional virtue — far removed from the heroes of our pacifistic, cowardly, miserly, neo-puritanical world, and a far cry from the overweight, innocuous Santa Claus depicted in contemporary advertising. Nevertheless, these essential traits never really went away, they were merely subsumed by mass culture.

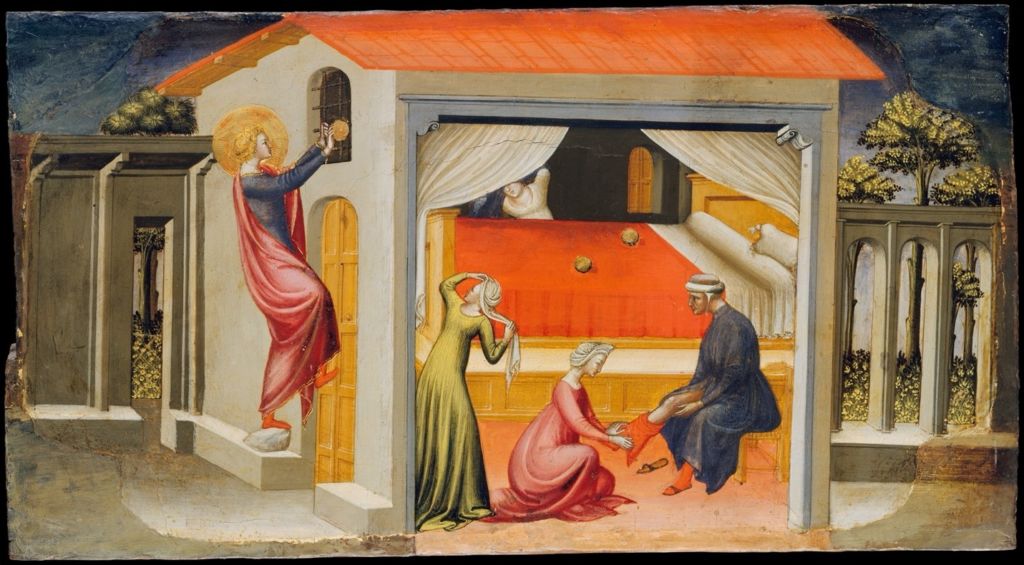

Now let us move forward into recorded history, to Saint Nicholas himself. It is a curious historical fact that this ascetic third-century Greek saint, with a reputation for ferocity in defense of the faith, should lend his name to the fat and jolly old elf of contemporary imagination. The major impetus for this historical evolution is the saint’s reputation for generosity. In the most famous incident of his life, Saint Nicholas learned of a father of three who had fallen into poverty; he was unable to afford a dowry for his daughters, and they were consequently at risk of being forced into prostitution. Saint Nicholas anonymously tossed three bags of gold into the father’s window at night, allowing the girls to be married and saving them from a life of infamy.

This episode secured Saint Nicholas’ lasting fame as a giver of gifts, so much that his feast day — December 6 — became the primary day of Christmastide gift exchange in Catholic Europe. One common practice, reminiscent of the older Norse traditions, was for children to leave out shoes and stockings for St. Nicholas to fill with treats the following morning. This practice was brought to North America by Dutch immigrants in New Amsterdam, whose quaint customs surrounding their Sinterklaas (popularized by Washington Irving in his History of New York [11]) led directly to the Santa Claus traditions of today. Of course, in time, the major gift-giving occasion was transferred from Saint Nicholas’ Day to Christmas. We have the Reformation to thank for this development; early Protestants, eager to abolish saint veneration but unable to get rid of Christmastime gift exchanges, changed the donor of the gift from Saint Nicholas to the Christkind Himself. But while Christ’s birthday became the new occasion for generosity, Saint Nicholas — in a considerably altered form from the saint of old — remained the more popular gift-bearing figure, despite the reformer’s efforts.

Two other stories of Saint Nicholas’ life are not as well known, and are likely apocryphal, but also add to his mystique. In one instance, Saint Nicholas is credited with miraculously reviving three young boys who had been kidnapped, murdered, and pickled during a time of famine by a butcher who intended to sell them as hams to unsuspecting patrons. This macabre story is in fact the primary reason for Saint Nicholas’ role as patron saint of children (yet not, surprisingly, of butchers). Another popular legend is that Saint Nicholas was present at the Council of Nicaea in 325, where he chanced to hear the infamous Arius discoursing on his heretical doctrines [12]. He was allegedly so incensed by Arius’ denial of Jesus’ divinity that he punched the heresiarch in the face [13]. Some scholars regard this as an unlikely story, since there is no evidence that Saint Nicholas was even present at the Council of Nicaea; however, others think that such behavior is so unbecoming of a saint that the story would not have been propagated unless it were true.

Regardless, in the historical Saint Nicholas (both the reality and the legend) we find several traditional characteristics: again, the lordly virtue of charity and generosity; the protection of innocence and children against the wicked; and a vigorous, warlike defense of orthodoxy and faith. And again, while these inherently Rightist traits — combined with the stern virtue and austerity of the saint — are not emphasized today, they constitute an important aspect of the historical Santa Claus legend.

Another key figure in the development of the Santa Claus myth is the English figure of Father Christmas. Though the names of Father Christmas and Santa Claus have been used interchangeably since the nineteenth century, Father Christmas took shape in the medieval era as a personification of the Christmas merrymaking. He was not, at that time, particularly tied to children or gift-giving rituals, and in fact was more commonly associated with the raucous drinking and feasting of medieval Christmastide. A carol [14] written by one fifteenth-century parson describes “Sir Christemas” announcing the news of Christ’s birth and encouraging his listeners to drink:

Buvez bien par toute la compagnie,

Make good cheer and be right merry,

And sing with us now joyfully: Nowell, nowell.

Father Christmas rose to prominence in the aftermath of the Puritan revolution. The Puritans, who regarded all traditional feast days as lacking scriptural basis and indelibly tainted by popish superstition and the remnants of pagan idolatry, banned all major feast days. Christmas, like Easter and Whitsunday [16], was to be just another working day, with any form of observance punishable by law. The dour fanatics were not entirely successful, as this was a deeply unpopular move not just to their Anglo-Catholic and Royalist opponents but to the mass of workmen and peasants, for whom such days offered a much-needed relief from the drudgery of their daily lives.

During this period, the benevolent and convivial Father Christmas thus became a political figure, demonized by Puritans as a debauched old lecher and drunk, and lauded by Royalists as a symbol of tradition, royal authority, hospitality, and the “good old days” of feasting and good cheer. Pamphlets [17] and poems were published during this time defending Father Christmas and his season of merriment against Puritan detractors, and by extension defending the traditional customs, Anglo-Catholic religion, and royal authority that had been recklessly swept away by the English Civil War.

[18]

[18]A Puritan (right) seeks to drive away Father Christmas, stating “Keep out, you come not here.” Father Christmas (center) responds, “Sir, I bring good cheere,” while a sympathetic onlooker exclaims, “Old Christmas welcome; Do not fear.” Frontispiece to John Taylor’s pamphlet The Vindication of Christmas (1652/3)

Thus, as with the previously discussed figures that contributed to the contemporary image of Santa Claus, Father Christmas is a personification of the lordly qualities of generosity and good cheer, an inveterate opponent of the Puritan killjoys who sought to ban festivity and merrymaking. He is also a staunch Royalist in politics, a true Cavalier [19], a guardian of Throne and Altar against the forces of revolution and cultural decay. Father Christmas is a nostalgic defender of Merry (pre-modern) England, and clearly a Man of the Right.

So how do these disparate figures come together in the contemporary Santa Claus? A brief and necessarily incomplete genealogy might run as follows: the third-century Saint Nicholas was venerated as a patron of generosity, and his feast day therefore became associated with gift-giving, particularly to children. In early modern England, the figure of Father Christmas came into being as a personification of holiday cheer. During the Victorian era, when many traditional Christmas traditions were revived (thanks to the efforts of Romantics and social novelists such as Charles Dickens [20]), Christmas became a more family-oriented affair, as opposed to the raucous festivities of the medieval era. Father Christmas became a giver of gifts, and as Santa Claus grew in popularity, the two figures merged.

Here we have a legendary figure who has taken many different forms over thousands of years, all of which share three essentially Rightist traits: 1) a virtue of lordly generosity and hospitality, in opposition to Puritan spoilsports and miserly Scrooges; 2) a loyalty to traditional authority — whether that of the Aesir, Christ the King, or the exiled Stuarts; and 3) physical vigor, acquired through battling frost giants, assaulting theological opponents, or playing the shockingly violent Christmas games [21] of old. (As a fourth quality, one might also include a certain [22] sartorial [23] flair [24], in contrast to the drab and uninspired attire of Puritan killjoys, miserly businessmen, and cynical Leftists.)

What, then, are we to make of the Santa Claus of today? Some of the changes are superficial, and do not substantially alter the legend’s character. As a nostalgic traditionalist, I of course prefer my Santa Claus to resemble a ragged Odinic wanderer rather than the portly, lobster-red soft drink spokesman embraced today; and I do not particularly care for the latecomer Rudolph, the feel-good invention of a Montgomery Ward ad man. But these do not change the essential nature of the legend.

No, the true betrayal of Santa Claus, this mythic figure so essential to the European consciousness, is to be found elsewhere. For one, there is his association with consumerism, credit card debt, and spoiled children. A personification of hospitality, generosity, and charity to the less fortunate has become an enabler of greed and selfishness.

Secondly, the contemporary Santa Claus has become totally innocuous, deprived not only of Odin’s spear and Saint Nicholas’ right hook but also of the Krampuses and Zwarte Piets and legions of frightening helpers [27] who once accompanied him to beat or kidnap ill-mannered girls and boys. Nowadays, Santa Claus does not even dole out lumps of coal to naughty children; he is simply a glorified, airborne postal worker, bringing toys to anyone who can pay regardless of the gift’s meaning or the worth of the recipient. While one might object to bribing children for good behavior with the promise of a material possessions, there is something to be said for Santa Claus being a figure of justice, who does not reward the wicked and good alike.

The greatest betrayal of old Saint Nick, however, is the commonsense assumption that Santa Claus is merely a “fairy tale,” a lie that parents tell children in order to bribe them for good behavior — or, at best, a white lie that parents pass down to give a little magic to their children’s Christmases. It is always assumed that that these children will eventually find out the “truth,” whether by hearing it from some know-it-all schoolmate or through their own budding sense of reason and logic. Santa Claus has been reduced from a godlike figure of generosity and justice to a mere tall tale, taking his place alongside the Easter Bunny and the Tooth Fairy.

While some might praise this development and argue that it is better than telling lies to children, this misses an important point. The decline of Saint Nicholas/Santa Claus is but one manifestation of a more general decline of religion, mystery, and authority in the world. Perhaps unintentionally, the Sicilian bishop (who ought to know better) has done his part to disenchant the world for his young flock, since denying the metaphysical reality of the figure of Santa Claus is tantamount to denying everything he represents. By rejecting the magic and mystery of this ancient figure, one who is firmly rooted in millennia-old tradition, the bishop has essentially bought into the modern view that the sacred and secular sides of the Christmas celebration can be divorced; one may go to church and remember “the reason for the season,” but everything else about the holiday is either a tedious, stressful obligation or an excuse for partying and overindulgence.

I would urge authentic Men of the Right to take a different approach. It should be evident by now that the War on Christmas is not simply a war against Christianity, but against the authentic spirit of Christmas itself, personified by the figure of Santa Claus, Sinterklaas, Babbo Natale, Père Noël, Father Christmas, Saint Nicholas, and the gift-bearing Odin. It is a war against innocence and all that is wholesome and pure in the European mythos. Honoring this legendary figure in all of his original majesty should constitute a major part of any traditional Christmas festivities. Rather than being the parent who tells their children that Santa doesn’t exist — and thereby, like ripples on a pond, accepting responsibility for the disillusionment of their entire social circle — let us maintain some of the magic and mystery associated with this season, which is intimately linked to our ancestral faith and virtues. If done properly, it is no lie to tell your child that Santa Claus exists. If your children understand Santa Claus not merely as an old fat white elf shimmying down a chimney, but rather as the spiritual personification of generosity, childlike innocence, and tradition, an angel of Christmas cheer [29], an archetype of God [30] in his benevolent and gift-giving aspect, whose example inspires people to acts of generosity, hospitality, and kindness during this holiest of seasons, then they will not feel betrayed when they come to doubt some of the story’s literalism. As the newsman Francis Church famously wrote in response to a classic question posed by eight-year-old Virginia O’Hanlon [31] in 1897,

Yes, VIRGINIA, there is a Santa Claus. He exists as certainly as love and generosity and devotion exist, and you know that they abound and give to your life its highest beauty and joy. Alas! how dreary would be the world if there were no Santa Claus. It would be as dreary as if there were no VIRGINIAS. There would be no childlike faith then, no poetry, no romance to make tolerable this existence. We should have no enjoyment, except in sense and sight. The eternal light with which childhood fills the world would be extinguished . . . No Santa Claus! Thank God! he lives, and he lives forever. A thousand years from now, Virginia, nay, ten times ten thousand years from now, he will continue to make glad the heart of childhood.

Santa Claus, like Christmas itself, is deeply rooted in the European soul and is a manifestation of its highest qualities. And like Christmas — and all the other ancestral traditions and holy days of our people — it is worth defending and preserving, for our children and for all who come after us.