Jamestown, the Virginians, & Leadership

Posted By Morris van de Camp On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled4,356 words

The Pilgrims who founded Plymouth Colony receive a great deal of glory. This glory is well deserved, but other shiploads of colonists did valorous things as well. The same year the Mayflower[1] [2] crossed the Atlantic, so too did the Bona Nova [3]. The latter vessel’s destination was Virginia, but it was swept northwards by the tides and wind. The crew recovered the situation by beat [4]ing against the wind back towards Virginia, arriving in January of 1621.

The Virginians, like those which arrived on the Bona Nova, are an important part of American culture. More English colonists went to Virginia than any other place. Many of America’s presidents came from Virginia or were of Virginia stock. Virginians were also often the first whites to settle in new places on the frontier. Among others, Virginia’s soldiers made the Ohio River Valley safe for European settlement, and the sons of Virginia’s original tidewater elite still occupy many important leadership positions in the United States today.

The Jamestown colony in Virginia is the oldest continuously-occupied English-speaking settlement in North America. The town today is not a particularly large one. It is situated in a low-lying area along the James River that contains a great deal of swamp- and marshland. Jamestown hosts an outstanding museum that has a replica fort, replica ships, and a replica Indian village.

The Virginia Company

The museum doesn’t replicate the most important part of the Virginia colony, however. The critical advantage the English colonists had was a corporation which raised capital by selling stocks. “Joseph Kelly [5], writes:

The Stockholders pooled their capital to underwrite enterprises that were too expensive for any individual to finance or too risky for any individual to hazard. The risk of losing a ship in the perilous sea routes . . . were spread among individual investors, who each owned just a slice of a voyage. (Kelly 30)

The Virginia Company grew out of corporate ventures to find new routes for sending English-made products to Russia. The company’s key financier was a man named Thomas Smythe [6]. Once the company was up and running, it outfitted a fleet of three ships commanded by Captain Christopher Newport, a highly experienced sailor who had lost an arm in battle. Most of the men in the expedition were English gentlemen. They would all have had some military training, but none of the skills of a tradesman.

This fleet — the Susan Constant, Discovery, and Godspeed — took four and a half months to get to Virginia, and by that time, one of its leaders, Captain Edward Wingfield, had encouraged John Smith’s arrest for attempted mutiny. When the fleet moored on the James River in 1607, the sealed orders were read and they proclaimed that John Smith was to be a captain. His chains were removed.

This article won’t focus on the whole of Captain Smith’s exploits or those of the other Jamestown colonists; they can be read elsewhere. I will instead examine the Jamestown colonists’ leadership decisions, as well as those of the Virginia Company’s directors.

The Virginia Frontier & Jamestown’s Leadership Structure

First, we need to understand that Captain Newport was a navy captain; the other captains were army captains. These ranks differed, Newport was clearly in charge when present. As far as age goes, Captain Newport was 46 years old in 1607, whereas Captain Wingfield was 57, Captain Bartholomew Gosnold was 36, Captain John Smith was 27, and Captain John Radcliffe was 58. (These weren’t the only captains at Jamestown, but they were the most important for this vignette.)

All of the captains were highly experienced explorers and leaders of men. All were social climbers. And all the gentlemen colonists with them were full of thumos, though none though really know what they are doing yet, so this thumos was often expended in unproductive ways.

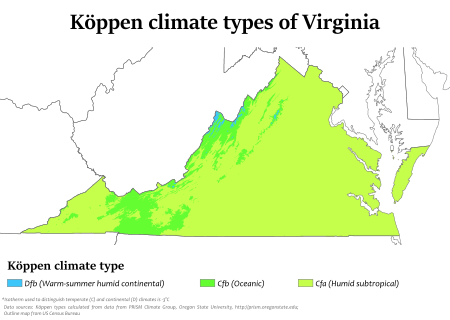

The Virginia climate is humid sub-tropical [7], meaning that it was every bit as cold as England in the winter but much hotter in the summer.

[8]

[8]The climate of Virginia is humid-subtropical (Cfa). Its winters are cold and the summers are typically long, hot, and humid. The colonists had woolen clothing and were unused to such heat.

The colonists picked the spot to fortify in a low-lying area not situated on the coast in order to keep the Indians away and make a potential attack by the Spanish easier to beat off. There wasn’t an easy way to accomplish their stated mission: to find gold and/or a water route to Asia. And then the hardships started.

The Englishmen’s constant companion was disease. These illnesses were likely the result of a vitamin deficiency called pellagra, as well as typhoid fever caused by ill-placed latrines and other unhygienic conditions. During the warmer months, the water in the James became saltier, so bad water became a factor as well.

The next problem was thumos-fueled political polarization that led to threats of mutiny, and occasionally mutiny itself. The colony was structured for social unrest from the outset. There were obviously too many gentlemen of high rank. They were not well-organized into companies under the command of a captain, who could then appoint sergeants from among the young gentlemen. Strangely, the Virginia Company commissions were issued in secret instructions that could only be opened upon arrival. There was no billet for majors or lieutenant colonels. Its leadership was therefore a shaky roundtable of equals.

The colony’s political polarization began after Captain Newport sailed back to England and Captain Gosnold [9] died. It is likely that Gosnold’s presence was the thing that prevented the colony’s leaders from falling out even earlier. Shortly after Gosnold’s death, Captain Wingfield was deposed as president and replaced by Captain Radcliffe.

Radcliffe later discovered a conspiracy to mutiny by one of the gentlemen, George Kendall. Kendall had been on the council, and may have been a spy for the Spanish. He was sentenced to death and shot by a firing squad.

Captain Smith was kidnapped by Indians in the meantime, but when he was eventually released and returned to Jamestown, Radcliffe was convinced that Smith had deliberately absconded. Smith was rescued from the gallows by Captain Newport’s return with supplies and more settlers.

[10]

[10]You can buy Greg Johnson’s The Year America Died here. [11]

Radcliffe’s suspicions regarding Smith were not unfounded. The colonists were aware that English soldiers in Ireland often left their respective forts and lived among the Irish. The equivalent at Jamestown was having colonists run off to join the Indians. Smith had also made a nuisance of himself on the voyage over. There was therefore lingering mistrust of Smith among many of the colonists. There was also no leading personality who got along with everyone else in charge after Captain Gosnold’s death.

Smith eventually became the colony’s leader. While deaths decreased under his leadership, he was very much a tyrant. He was the one who first made the famous statement that those who don’t work won’t eat — which in practice really meant that those who didn’t do what Smith wanted them to do wouldn’t eat. Smith’s leadership did save the colony in the short term, however. His best decision was to separate the group into smaller colonies. He allowed bands of men to occupy various points along the Virginia Peninsula and then fend for themselves.

In the meantime, the Virginia Company’s directors managed to conduct a solid appraisal of the colony’s prospects and needs from various sources, including Smith’s assessments. As a result, their later resupply missions brought far more skilled tradesmen.

One ship with such colonists, the Sea Venture, ended up shipwrecked on an uninhabited island in the Bahamas on July 25, 1609. The passengers and crew built two new ships out of the Sea Venture’s remains as well as local timber, and headed to Jamestown. When they arrived, only around 60 of the original colonists were still alive. They decided to return to England, but Thomas West, Baron De La Warr, arrived with another fleet, saving the colony. In October of 1609, Captain John Smith was burned in a gunpowder explosion and returned to England. Thereafter the colony became less polarized, but was still something of an all-male mining camp.

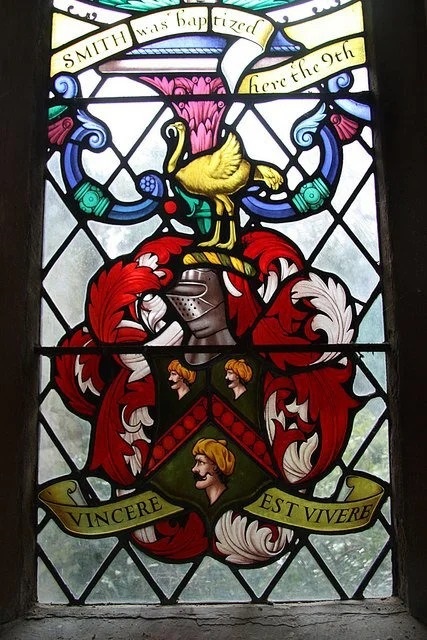

[12]

[12]John Smith was from a family of well-to-do Yeomen. He was awarded a Coat of Arms while serving as a mercenary soldier fighting the Ottoman Turks in Eastern Europe. During a siege, he beheaded three Turks in a contest of single combat.

An After Action Review of Jamestown’s Leaders & Thumos

Psychologist Bruce Tuckman [13] postulated that groups go through a sequence of Forming, Storming, Norming, and Performing. This means that a group forms with high expectations but no clear idea of what is going to happen or what exactly they should be doing. Then, the various individuals’ working methods clash. Finally, norms of behavior are established, and then the group goes about successfully completing its mission. This is certainly what happened in Jamestown, although the colony didn’t begin to perform well until after the Virginia Company went bankrupt and the colony became governed directly by the Crown.

I suspect that had Captain Gosnold survived, the colony would not have polarized so quickly and more people would have lived. Furthermore, I believe the colony survived in spite of Smith rather than because of him. Radcliffe probably had a large coalition of anti-Smith supporters behind him who had developed Jamestown into a livable settlement while Smith had been in Indian hands, and they thoroughly resented Smith for having been absent. From their point of view, the “captivity” story might have been a lie. Since we know now that Indians captured whites as a policy, we also know that Smith wasn’t lying, but in 1608 this hadn’t been established yet.

Additionally, Smith had won his coat of arms in the most heroic way possible: by killing and beheading three Turks in single combat. He would have bragged about his exploits and perhaps got on the nerves of those gentlemen who were too young to have fought the Turks, but were nonetheless brave enough to volunteer to create Jamestown.

[14]

[14]You can buy Greg Johnson’s It’s Okay to Be White here. [15]

What could have been done better? Obviously, there were too many gentlemen on the first expedition to Jamestown, but it is entirely possible that only gentlemen seeking to earn their spurs would have volunteered. Perhaps Radcliffe was right to presume that Smith was engaged in questionable behavior. Had Smith been hanged, Radcliffe’s political position would have been secure and the colony might have politically stabilized earlier.

In modern circumstances, a “Radcliffe” doesn’t need to hang a “Smith.” I know a military officer who served in the early stages of the Iraq War, and he later recounted that he had known who the troublemakers were before taking over a major staff section, and had pre-planned rotating them out of the region using a bureaucratic process and Black Hawk helicopters.

There are three reasons to fire someone — or in dire circumstances such as those in Jamestown in 1607, hang or imprison them: misconduct, mutiny, or a failure to master the task at hand (which admittedly doesn’t justify hanging or imprisonment).

In the same way that a one-eyed man is King among the blind, a man who knows how to keep his temper and immediately size people up is King in a high thumos environment. In Jamestown, it is clear that captains Newport and Gosnold were better at managing thumos and that captains Radcliffe, Smith, and Wingfield were less capable.

Managing high-thumos men is quite difficult, but from what I’ve seen, being a veteran helps, and being older than most of the other men helps even more. Even then, however, it is still difficult. In Jamestown, all the captains were veterans. When Smith divided his colony, he undoubtedly sent the people with whom he had problems away. That’s another solution.

A possible way to have managed the situation on the ground, would have been to appoint a major or lieutenant colonel, arrange the group into companies and platoons, and then appoint sergeants from among the gentlemen. Another approach would have been to get as many people involved in defining the group’s most critical problems and then getting the subordinates — not the leader — to come up with the solutions. This could have been accomplished in a town hall-style meeting.

Unfortunately, this might not work well in a polarized environment since a town hall can end up being dominated by one malcontent. In that case, the “in group,” loyal to the leader and competent in ordinary matters, need to be the ones coming up with the ideas and attending the meetings.

In the end, the Jamestown colony survived because the Virginia Company in London was able to continuously raise capital and keep sending supplies and settlers.

Governor Berkeley & the Second Sons of Rural Southern & Western England

It isn’t until after the 1620s that the Virginia colony starts to be something of a self- sustaining community. It truly begins to take off when one extraordinary leader arrives: Sir William Berkeley.

[16]

[16]Sir William Berkeley’s pose in this portrait indicates that he was a Royalist and sympathetic to King Charles I’s cause during the English Civil War.

Governor Berkeley was born in London and spent his youth between that city and Berkeley Castle in Gloucestershire. He very much held the vices of the times in which he lived: He bullied those of lower rank, fawned on those above him, and used his office for private gain. He was commissioned as a governor in 1641. He shaped the colony by encouraging “distressed cavaliers” from England to migrate to Virginia. His chief recruits were the second sons of England’s gentry. Ultimately, this group would come to dominate all of Virginia east of the Blue Ridge Mountains, as well as the tidewater region of Maryland and southern Delaware.

[17]

[17]In heraldry, the crescent moon indicates a second son. This symbol is everywhere in the South and shows the spread and influence of Virginia’s tidewater people.

While he recruited gentry from all over England, two particular regions sent a great many gentlemen and their servants, and quickly took the lead. The first was London and its surrounding suburbs, the second was 16 counties in the south and west of England. It was the same part of England which had remained loyal to King John during the 1215 Baron’s Revolt.

[19]

[19]The same area that was loyal to King John in 1215 was loyal to King Charles I at the outbreak of the English Civil War.

Prior to the Norman Conquest, this was the part of England that had the most slaves. After the Normans came, it became the area with the most serfs. Indeed, most of the servants recruited to work in Virginia came from within a day’s ride of Bristol and London.

In England’s south and western regions, the sense of social obligations between laborers and landowners remained strong in the seventeenth century. Radical Puritan ideas didn’t take hold. Instead, the population remained devoted to the High Church and was liturgical.

The southern accent also originates from this region. David Hackett Fischer writes:

These Virginia speech ways were not invented in America. They derived from a family of regional dialects that had been spoken throughout the south and west of England during the seventeenth century. Virtually all peculiarities of grammar, syntax, vocabulary and pronunciation which have been noted as typical of Virginia were recorded in the English counties of Sussex, Surrey, Hampshire, Dorset, Wiltshire, Somerset, Oxford, Gloucester, Warwick or Worcester. (Fischer 259)

Those who claim that the Southern accent is influenced by African speech, such as Joey L. Dillard, are usually radicals or Marxists. They are misreading the data.

Those with Royalist backgrounds in tidewater Virginia include George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Monroe, and later George C. Marshall. Marshall

was born in Uniontown, Pennsylvania, but he considered himself a Virginian. He was related to the Taliaferros [20], Pendletons, Randolphs [21], Catletts [22], and Carters, but his family roots were in the Northern Neck. His royalist ancestor Captain John Marshall arrived in Virginia in 1650 . . . (Fischer & Kelly 318)

All these men, and many more of lesser renown, expected to be leaders in their society and dealt with whatever storms fate had in store for them as leaders to the best of their abilities. They imbibed the basic principles of leadership in their childhoods. George Washington’s “Rules of Civility [23]” is a good example of that training. Ultimately, their leadership talent grew out of their aristocratic heritage. They had a way of managing complication versus complexity [24] that made for a healthy society.

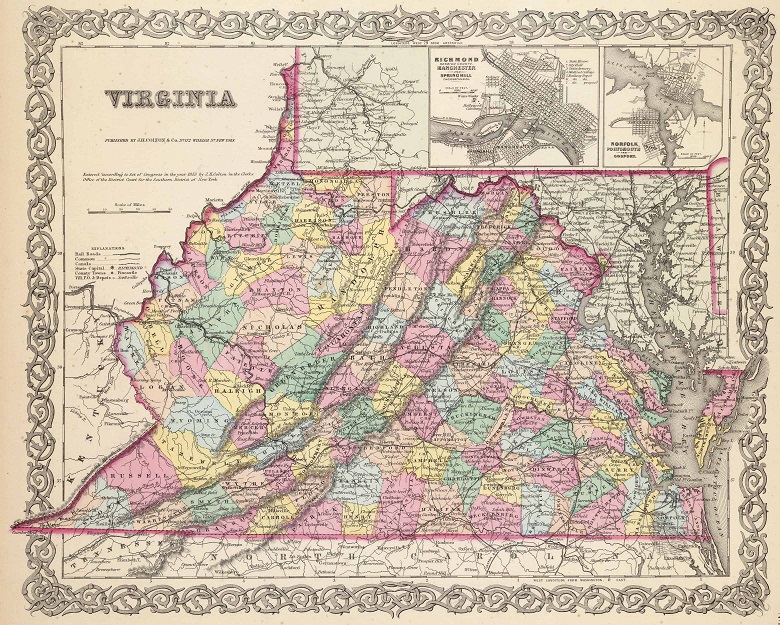

Virginia West of the Blue Ridge Mountains

Virginia’s charter essentially included all of North America save New England, Pennsylvania, and Maryland. The Virginians therefore felt that they had the right and duty to expand. On the eve of Lord Dunmore’s War against the Shawnee Indians, there was a contingent of Virginia militia who attempted to capture western Pennsylvania for Virginia. That contingent didn’t win Pittsburgh for the Old Dominion, but they did get most of the Ohio River Valley. Virginia prior to the Civil War was very large, comprising both what is Virginia today as well as West Virginia. After the War of Independence, Virginia ceded its western claims to the United States government, receiving for example the Virginia Military District in Ohio in exchange.

[25]

[25]By 1790, Virginia had expanded to the bank of the Ohio River. However, the state effectively contained two different Anglo groups. In the east were the tidewater Virginians. In the west were Pennsylvanians, most of whose origins were in England and Scotland’s borderlands as well as Northern Ireland.

Virginia west of the Blue Ridge Mountains is different, however. Madison Grant writes:

While a purely Nordic population was thus occupying tidewater Virginia east of the Blue Ridge, another Nordic invasion from a wholly different source was entering upland Virginia on the other side of the mountains. The Shenandoah Valley is virtually an extension of the interior valleys of Pennsylvania; and while an occasional pioneer pushed his way to it through the mountains from the eastern front, the real settlement came through the side door beginning around 1725 and reaching the proportions of an invasion about 1732. (Grant 137)

In other words, the western portion of the Old Dominion is made up of Pennsylvanians. The Shenandoah Valley looks like any valley in Pennsylvania. These settlers were a combination of different groups, and they brought to Virginia several new tools for economic and racial expansion.

Pennsylvania is unique in that it successfully corralled several diverse groups of whites to make a coherent social whole. The first whites in Pennsylvania were colonists sent by the Swedish Crown [26]. It is likely that the buckskin and fur cap hunting ensemble developed in Finland came to America with the Swedish colonists. The Scots-Irish arrived from northern Great Britain and Ireland [27] to settle the back country west of Philadelphia, and the political and economic elite of the lot were the Quakers. Morgantown, West Virginia was founded by Colonel Morgan [28], a Quaker. Allied to the Quakers were Germans from various Christian sects.

The Virginians’ Expansion

[29]

[29]Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois became part of the United States when a militia of Virginians commanded by George Rogers Clark went on a successful campaign to capture the British forts on the Ohio River. Clark was a tidewater Virginian whose family were prominent citizens in King & Queen County.

[30]

[30]You can buy Greg Johnson’s The White Nationalist Manifesto here [31]

While many of the Virginians headed west had roots in Pennsylvania, they expanded under the political leadership of tidewater Virginians and their institutions. The Cumberland Gap, through which the Pennsylvania-born English/Welsh Quaker Daniel Boone led settlers, was discovered by Thomas Walker, a tidewater Virginian. The buckskin-clad frontiersmen serving on the Illinois Campaign in 1778/9 were led by George Rogers Clark, who was also from tidewater Virginia. Examining the casualties from an accidental gunpowder explosion that were recorded during the Illinois Campaign demonstrates the fusion of European elements in Virginia. One of the officers killed was Major Jacob Bowman [32], the son of a prominent German settler in the Shenandoah Valley. The other was Captain Edward Worthington [33], an (Anglo)-Irishman.

There is also a regional pattern to the migration out of Virginia:

The great outpouring of people from Virginia tended to flow in distinct streams, not only to particular destinations outside its boundaries but also from specific regions within the state. The first great flow of emigration to the Carolinas came from [Virginia’s] Southside and the southern parts of the Shenandoah Valley. The second wave left from the Valley of Virginia to the Southwest, from the piedmont to Kentucky, and from the Northern Neck, western Virginia, and the northern Valley to the Ohio Country. (Fischer & Kelly 141)

A way to see where middle-class Virginians settled is where the I-Houses are. The I-House is a basic structure with distinctive proportions: one room deep, two stories high, and three bays wide. The I-House was developed in Virginia and was elevated to avoid rot from damp conditions; it is easy to heat in winter and cool in summer.

[34]

[34]The I-House shows the location of Virginian’s westward expansion. They are especially prominent in the southern portions of the “I states” of Indiana and Illinois.

Virginia’s tobacco-based plantation economy eventually depleted the soil in Virginia. At the same time, the expansionist policies of Virginians such as Thomas Jefferson, George Rogers Clark, and William Henry Harrison opened up new lands in the west (often Cfa climate zone). As a result of these factors, as well as a high birth rate, the Commonwealth of Virginia had a population that was raised in the state but who left it upon reaching adulthood.

It is estimated that “in the period from 1790 to 1840 the Old Dominion lost more inhabitants than did all of the original states above the Mason-Dixon combined” (Fischer & Kelly 137). Virginia supplied a population equal to that of the state of Mississippi in 1840 to the west every decade.

[35]

[35]The location of the Cfa climate zone in Illinois roughly matches up with the settlements of Virginia stock-whites. From places like Illinois, Virginians went on to settle Missouri, the prairies, and beyond.

The Truman Administration: Virginians & the Liberal-Minority Coalition

The presidency of “Give ‘em Hell” Harry Truman has all the elements of Virginia’s cultural impact upon America. Truman was from Missouri. He considered himself an unreconstructed Southerner. He was mostly Scots-Irish, and most of the lines of his ancestry [36] run through Virginia. They included a man of tidewater gentry stock named Captain Robert Langley Tyler [37]. One of Truman’s secretaries of state was George C. Marshall, who was pure tidewater gentry.

Truman was aware of the JQ and a race realist, but he was in a party that had a nuthouse and a J-Left wing that he had to appease. His presidency therefore had two sides: one of brilliant success, the other of terrible calamities whose effects continue to plague America today. Truman’s successful policies were based on the tidewater Virginians’ leadership excellence and the failures stem entirely from the Semitic schemers within his administration.

Truman’s successes included stabilizing Europe following the Second World War, defending South Korea and setting it upon a path to prosperity, and creating a system that contained — and ultimately destroyed — the Soviet Union. In this regard, the Marshall Plan was critical. Named after the Secretary of State of the time, it was not really Marshall’s plan; it was Truman’s plan. But the President recognized that a “Truman Plan” wouldn’t make it through Congress, so in aristocratic fashion, he was big enough to let someone else get the credit. Implied in the Marshall Plan was burying the hatchet with Germany. There was no Semitic-style quest for vengeance after the Berlin Airlift.

One might look back at Truman’s decisions in the late 1940s and say he had it easy. This was not so. At the end of the Second World War, one could look back for 200 years and see war after war between Germany and France. There was no reason to suppose that anything Truman was doing would bring that dark and bloody legacy to an end. Only people with a history of successful rule, such as tidewater Virginians, could have pulled off stabilizing Western Europe.

But Truman’s Jewish staff were a disaster. Truman recognized Israel and America has had Zio-messes ever since. One Zio-mess, the Iraq War, cost $1.922 trillion and thousands dead. The primary result of that fiasco was an increase in jihadist terror. Other Zio-messes include “civil rights” and the integration of the armed forces. Henry Dexter White [38], a Jewish spy for the Soviets, served in the US Treasury and possibly blocked loans to China in order to facilitate a Communist takeover there. The Soviet Union also was able to develop the atomic bomb based on information from Jewish spies in the US in 1949. The fall of China and the Soviet bomb led to the Korean War, so in a sense that was a Zio-mess as well.

Truman’s refugees ended up creating a missile industry in Huntsville, Alabama. Today, the Jew George Soros’ activities [39] are like the Marshall Plan in that money is spread around and there’s talk about “democracy,” but the results are wildly different. The Marshall Plan led to lasting peace in Western Europe, but Soros’ Open Society Foundations have led to one war after another in the former Soviet Union. Refugees today consist of knife-wielding savages on the breadlines. Soros-funded district attorneys support crime. The ongoing Soros-funded Zio-mess seems like evil for evil’s sake [40].

If one is of Virginia-stock heritage, the way to preserve that heritage is to marry and have children, obey the law, work hard, and be involved. Sic semper tyrannis!

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[41]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[41]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.

Bibliography

David Hackett Fischer, Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989).

David Hackett Fischer & James C. Kelly, Bound Away: Virginia and the Westward Movement (Charlottesville, Va.: University of Virginia Press, 2000).

Madison Grant, The Conquest of a Continent (York, S.C.: Liberty Bell Publications, York, 2004).

Terry G. Jordan & Matti Kaups, The American Backwoods Frontier: An Ethnic and Ecological Interpretation (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989).

Joseph Kelly, Marooned: Jamestown, Shipwreck, and a New History of America’s Origin (New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2018).

Note

[1] [42] Isaac Allerton [43] (1627–1702) was descended from Mayflower passenger Isaac Allerton, Sr. and Fear Brewster [44]. He went from Plymouth Colony to Virginia and became a member of the House of Burgesses. Many old-stock Virginians are Mayflower descendants through the Allerton/Brewster connection.