Christmas & the Yuletide: Light in the Darkness

Posted By William de Vere On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledLike many children, some of my most vivid early memories center on the Christmas season. Preparations always began immediately after Thanksgiving. My mother and I would drag the dusty boxes of decorations down from the attic, while my father ascended onto our rooftop to string up the lights. A few weeks later we would go to the tree farm, ideally on a cold and overcast day, where my sister and I would run around searching for the ideal Christmas tree to be felled by my father’s handsaw. Outside the home, my small Southern town was enveloped in an atmosphere of festivity. Downtown storefronts were brightly decorated, and the streetlamps wrapped in lights and evergreen. Almost every home in the neighborhood had some decorations or greenery commemorating the holiday. There was a palpable feeling of excitement among my schoolfriends as the winter break approached, and the last day of the semester always featured a Christmas party and sharing gifts among classmates.

This most evocative of seasons has many different sights, odors, and sounds associated with it. No matter how many years have passed, the scent of evergreen, cinnamon, cloves, and gingerbread always carry me back to the Christmases of my childhood, wherever I might encounter them. I still distinctly remember the feeling of walking through the cold woods behind my house at dusk, quiet but for the sound of leaves crunching beneath my feet, the smell of woodsmoke in the air, as the Sun disappeared behind the bare tree limbs and the stars began to appear. Standing in the dark, cold woods, I could see the bright Christmas lights of the houses nearby, sometimes glimpsing the decorated trees and gathering families through the windows. Everyone has certain foods and drinks they associate with this time of year (eggnog is a personal favorite). Music was always an important part of the season; I grew up loving the traditional carols, particularly the more melancholy ones, though in adulthood my tasted turned to medieval and Renaissance Christmas songs.

I think and write a great deal about the seasons and holidays in part because they form the most vivid memories of my youth and are a continuing source of delight and reflection. Even as a child, I was particularly attuned to seasonal changes, as I suspect many children are. I was especially fond of autumn, Halloween, and the beginning of the great three-month winter holiday season. It is easy to attribute this to a simple childish excitement over candy, toys, and a few weeks’ freedom from school, but I’m certain it goes deeper than that. I loved the different feel of the air, the changes in the plants and trees, the music, the decorations for each season and the meaning they held for me even at a young age. I had a love of ritual, like many children, which has remained with me into my adult life. I also believe that these seasonal changes in the natural world and in the community, the changing mood at home and school and about town, the sheer beauty of Earth and indeed of mankind at certain points of year, gave me my first intimations of the divine.

Children are especially attuned to these seasonal transitions, I think, because such transitions represent a kind of change without progression. Even while they are growing, their bodies and minds and circumstances changing, up to a certain age all children live in an eternal present — there is a cyclical nature to all these changes they experience, represented most vividly by the yearly return of the seasons and school year. If the essence of high spirituality is to see beyond the veil of time and live in eternity, then childhood represents the purest, though unconscious, form of immanence. As we grow older and become more focused on the future, and on nursing the grievances of the past and ruminating on the present’s cares, we lose this intimate connection to the magic latent in all things.

However, for those who have maintained to some extent the sense of wonder and ritual from our childhood, the change of seasons and the festivals that punctuate the year present great opportunities for growth. As we get older our natural magical perception of nature is transformed into a deeper religiosity, and we gain a deeper sense of the spiritual significance of our holidays and seasonal festivals. The ritualism also takes on a higher dimension. Every year, these days become an opportunity for reflection, showing us how we have grown intellectually, emotionally, and spiritually. It gives order to the passage of time, freeing us from the wheel of randomness, chance, and sheer purposelessness that characterizes much of modern life.

There is, I believe, no season of greater importance and joy to the European soul than the Yuletide and its festivals, centering on the celebration of the winter solstice and Christmas. There is something about the winter, the return of the Sun, and the celebration of light in the darkness that deeply appeals to our Faustian nature. While I am no slave to tradition, I maintain that certain traditional practices, such as old-fashioned holiday celebrations, are indeed a reflection of perennial truths and must therefore be defended against the innovations or dismissals of an arrogant modernity. I am of one spirit with the old squire in Washington Irving’s recounting [3] of Christmas in old England, who viewed it as his special duty to keep the good old ways alive on his country estate, even as they were falling out of fashion elsewhere. For the remainder of this essay, I will briefly examine some of the ancestral European holidays and practices surrounding this most sacred of times.

Of course, this time of year is so rich in millennia-old tradition and meaning that it will be impossible to do justice to it all. Indeed, the persistence of these celebrations across time, and the numerous customs that have gathered about them, speak to its singular significance to the European soul.

Yule & Midwinter

For Europeans of northern descent, the oldest known festival of the wintertime is the Germanic celebration of Yule. This religious feast occurred at the winter solstice, the darkest time of the year, and centered on the sacrifice of livestock that could not survive through the winter as well as plentiful consumption of ale. Toasts were drunk to Odin for “victory and power to the king,” to the gods Noldor and Freya for “good harvests and peace,” and to the memory of departed kinfolk. Many of our contemporary Christmas traditions can be traced to this festival, including the use of evergreen decorations as a symbol of living nature in the dead of winter; the burning of the Yule log as an emblem of divine light; the feast of the Yule boar or Christmas ham, which can be traced back to the sacrifice of boars to Freya during the Yule festival; and wassailing, the practice of singing door-to-door with a wassail bowl and blessing orchards with incantations.

[4]

[4]Asgårdsreien [5] [The Wild Hunt of Odin] (1872) by Peter Nicolai Arbo [6]

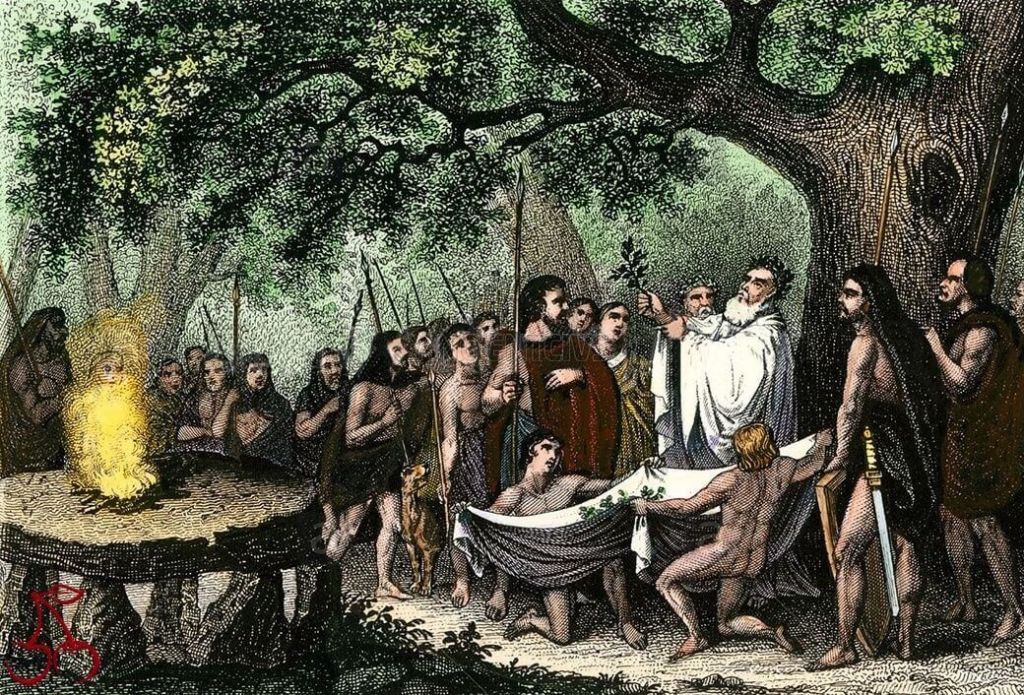

Though sources are sketchy, some scholars and neo-pagans speculate that similar activities took place during the Celtic winter solstice festivals, now known by the neologism Alban Arthan. It was at this time of year, some maintain, that the Druids gathered the sacred mistletoe (hence its relationship to Christmas, though it was held in suspicion even into recent times for its pagan connotations). The winter solstice is associated with the death of the Holly King — symbolizing the dying Sun and the old year — at the hands of his son the Oak King, symbol of the new year and the ascendant Sun.

It goes without saying that the Yule celebrations of the North have played an essential role in the development of Christmas customs. Some neo-pagans have sought to excise the Christian dimensions of this holiday and return to a more primeval and purportedly authentic celebration of the winter solstice. As Wilhelm Beilstein [9] wrote in 1939:

Christmas is to us Germans the most lovely and meaningful season of the year. From it, we gather inner strength and power from the eternal life force of our nature. Mother and child, family and kin are at its center. It is not limited to a day that swiftly passes, but rather it encompasses a long period of preparation and many mythic beings and customs. Despite many foreign influences, over the course of centuries it has remained an ancient German holiday, and its nature can only be understood within the territory of our people. Today, we have once again come to know the true meaning of our Christmas customs and traditions, freeing them from foreign names and influences.

[10]

[10]You can buy Collin Cleary’sWhat is a Rune? here [11]

It is commonplace for contemporary neopagans to accuse Christians of “stealing” the Yule traditions of old, as well as those of other holidays. On the flip side, fundamentalist Protestants likewise reject many of these traditions (and some the holiday itself) for their pagan, “papist” associations. Both sides are too simplistic in their views. It is more accurate to say that these ancestral traditions were simply adopted into the syncretic Catholic faith, transformed but not losing their essential meaning and significance. Another such holiday whose purpose was transformed but whose rituals and symbolic meaning were preserved was the Roman Saturnalia, to which we will now turn.

Saturnalia and the Sol Invictus

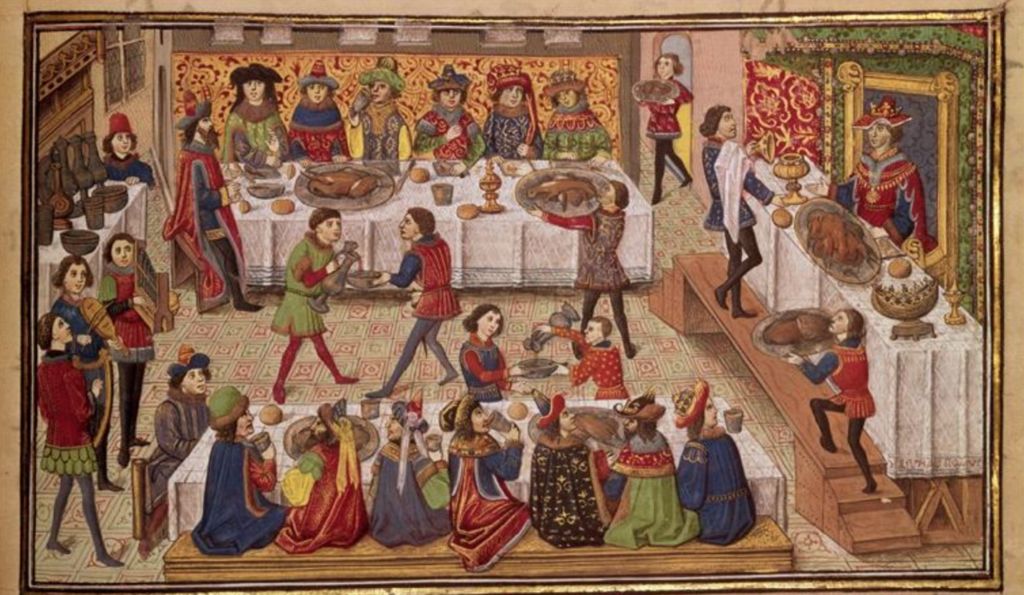

For the Europeans of the South, the most important celebration of the winter — and, indeed, the most popular of the year — was Saturnalia [12]. It was the celebration of Saturn, the Roman god of agriculture and time, and was traditionally observed as a week-long festival beginning around December 17. It appears to have been derived from an even older ritual of offering gifts and sacrifices to the gods during the winter sowing season. During this holiday, Romans would put aside their somber traditional togas and dress in more festive and colorful vestments called synthesis. They decorated their homes with wreaths and greenery and lit candles called cerei, symbolizing light returning after the solstice. It was a period when no servile work was to be performed, no wars waged, and no trials held. Romans would spend the days gambling, singing, socializing, and giving gifts. Even slaves did no labor, and were allowed to participate in the festivities; in some cases, the roles of master and slave were even reversed for a time.

In addition to its function as a midwinter agricultural festival, Saturnalia had another theological meaning. Greeks and Romans held that there was a time when the god Saturn ruled the Earth, and regarded this period as a Golden Age when men lived like gods, free from care and death, a time of limitless freedom and bounty. The Saturnalia festival, with its feasting and freedom from labor and generosity toward one’s fellow man, might be considered a temporary restoration of this Golden Age on Earth. The parallels here to the Christian feast of Christmas are quite obvious, as are the practices of hanging greenery, giving gifts, holding parties, and even the reversal of social roles that characterizes the Twelfth Night celebration (discussed below).

Another parallel is the celebration of Natalis Invicti [14], the birth of Sol Invictus (“unconquered Sun”). The religion of this Sun god was institutionalized in the late Roman Empire, and may have been part of an attempt to restore the ancient cult of Sol. It was strongly associated with the imperial family and prominently featured on official coinage. Its festival was held on December 25, which has of course led to the widespread belief that the date of Christmas was intentionally chosen in order to displace it (more on that below). The Sol Invictus was associated with the cult of Mithras, which was a serious rival of early Christianity and also honored a monotheistic god and redeemer. The comparison of Christ with the Sun was a common theme in early Christianity, making the winter solstice a fitting time to honor the birth of both the physical and the divine Sun.

Christmas in Christendom

Christmas is, of course, a celebration of the birth of Christ. Since the actual time of Jesus’ birth is not mentioned in scripture, the date of December 25 was not formalized until the fourth century by Pope Julius II. As mentioned above, some speculate that this date was chosen in order to supplant the extant celebrations of Saturnalia and the Natalis Invictus. Another line of thought holds that the date was chosen because of the significance of Christ’s death: It was commonly believed in that era that Christ was conceived on the same date he died, which was held to be March 25 (since Christ died at Passover, which was celebrated on that date). Thus, if he was conceived on March 25, he was assumed to have been born nine months later, on December 25.

Whatever the reason for choosing this date, it was fortuitous, and it is now exceedingly difficult to imagine a Christmas celebrated at any other time of year (I cannot help but feel pity for European descendants in the southern hemisphere). From its inception through the European Middle Ages, the Christmas feast became one of the most important celebrations of the year, occupying the pride of place once bestowed upon Yule and Saturnalia. While the joyless Puritans who gained control of England in the mid-1640s attempted to abolish Christmas [16] and its ancestral customs in England and in the New England colonies (just as certain Stoics [17] disapproved of Saturnalia’s excesses), they never fully succeeded. Indeed, Royalist pamphleteers who opposed Puritan rule came to associate the old traditions of Christmas with the cause of King and Church, and cast Father Christmas as the symbol and defender of the “good old days” of feasting and good cheer. Some of the old ways were lost, but enjoyed a great revival during the Victorian period, thanks in no small part to the Romantic movement and writers such as Washington Irving [3] and Charles Dickens [18].

Festivities aside, for Christians, of course, the holiday possesses a special significance as the commemoration of their Lord’s birth, when the divine became incarnate in human flesh and began His earthly campaign against the forces of darkness. The feast was therefore preceded by a period of introspection and purification, known as Advent. The meaning of Advent was threefold: a period anticipating the birth of Christ in time, the eventual return of Christ as King, and the continual birth of Christ within the individual soul. In medieval Europe, Advent was a period of fasting and abstinence intended to encourage a reverent and contemplative frame of mind. While less rigorous than Lent, the Advent fast still involved significant restrictions, including abstaining from virtually all animal products: It was believed that such a diet was more akin to the diet of Adam and Eve before the Fall, allowing one to come closer to man’s primordial purity. While the Advent fast is hardly observed nowadays, and the month preceding Christmas is a free-for-all of sensual indulgence and consumption, I find that it is salutary to observe a period of austerity in order to better appreciate what one has and open oneself more fully to this season’s beauty and magic.

When Advent concluded on Christmas Eve, the party began in earnest, traditionally lasting twelve days. Some of Christmas’s major traditions, which were borrowed from Yule, Saturnalia, and other European midwinter celebrations, have already been mentioned: the ubiquitous evergreen, mistletoe, and holly decorations; the pervasive use of candles and lanterns, and their association with the return of light in the darkness; public singing, revelry, feasting, and gift-giving; and a magical and spectral gift-giving figure. In Catholic Europe, with the dietary restrictions of Advent finally lifted, a season of great feasting was underway, with roast boar and goose, mince pies and puddings, and all manner of delicacies baked to mark the occasion. Mulled wine, cider, strong ale, and other drinks were also heartily consumed at this time, as the following thirteenth-century Anglo-Norman carol [20] makes clear:

Lordlings, Christmas loves good drinking,

Wines of Gascoigne, France, Anjou,

English ale that drives out thinking,

Prince of liquors, old or new,

Every neighbour shares the bowl,

Drinks of the spicy liquor deep;

Drinks his fill without control,

Till he drowns his care in sleep.

There are many other Christian holy days that occur throughout the twelve days of Christmas — the feasts of Saint Stephen, the Holy Innocents, Saint John the Evangelist, Saint Sylvester, and of course New Year’s Eve and Day — whose unique traditions and significance cannot be discussed fully here. However, in concluding this section, I would like to focus on the final days of the historical Christmas celebration: Twelfth Night and Epiphany.

The Twelfth Night celebration, which takes place on the eve of Epiphany (January 5), was perhaps the night of greatest revelry in the whole season. It shares many features with the Roman Saturnalia: on this day of drunken carousing and licensed disorder, masters would dress as servants, servants as masters, women as men, and vice versa; children would be appointed lords of misrule, commanding their parents and other adults to perform acts of absurdity; in short, a generally topsy-turvy attitude prevailed. This is captured in Shakespeare’s play of the same name [21], which includes its fair share of gender inversion and revelry (and also lampoons the Puritan attitude through the uptight bore Malvolio, whom another character asks, “Dost though think because thou art virtuous there shall be no more cakes and ale?”). Despite its connotations of drunkenness and disorder, even Twelfth Night has an important religious significance: it represents the inversion of values present in the Incarnation, with the King and Liberator descending to Earth disguised as a poor child in a manger.

[23]

[23]You can buy Greg Johnson’s Truth, Justice, & a Nice White Country here [24]

The concluding celebration of Christmastide — Epiphany (January 6) — is of especial theological import. Epiphany commemorates the arrival of the Three Magi at the side of the newborn Christ. With the arrival of these three wise men of the East, the manger scene is complete. The divine angels mingle with mortal men, the beasts of the field and farm, and even the very stars in the sky, uniting the divine, human, and natural worlds in paying homage to the Son of God. Kings worship with common shepherds, old with young. The Magi hail from distant lands (traditionally understood to be Persian, Arabian, and Indian), uniting the philosophical and religious systems of the Indo-Aryan with those of the Abrahamic religions, just as Christianity would later absorb the best insights of Greece and Rome. In short, the manger scene is reflective of the ultimate synthesis that Christianity, at its best, aspires to be: a synthesis of all that is true in world religion, philosophy, and science.

Having completed this brief and necessarily incomplete tour through the European midwinter celebrations, I will venture a brief meditation on its significance to contemporary Men of the West.

The Golden Age & the Return of the Light

In “The Artifacts of Christmas: Saturn and Solstice [25]” published by Aureus Press — a fascinating and highly recommended essay — the author lists several features shared by all of these ancestral European midwinter festivals, many of which we have already touched upon:

1) An elected overseer, the Princeps/Yulefather/Lord of the Bean, who may also represent a Santa Claus figure.

2) There must be a light show over the duration of the holiday, candles or stringed electric lights in our case.

3) The holiday must go for a period of days, at least a week.

4) For some the season is too much and they cry humbug.

5) Decorating trees.

6) Certain plants are sacred to this time: holly, mistletoe, oak.

7) Stockings play a part, from the foot of Saturn himself, or hung over the fire awaiting gifts.

8) Gift giving.

9) Wassailing/caroling, going to strangers doors.

10) Gluttonous feasting and drunkenness.

11) Relaxation of law, business closes.

12) A time of truce and goodwill.

13) Must take place around the dates of the winter solstice and refer to our star: the Sun, which today we may have replaced with the North Star.

14) Role reversal: those normally in charge make kings of the lowest.

15) Spirit of charity.

16) Colorful clothing, special hats.

17) The sickled figure of Father Time (ghost of Christmas future) and unknown alter ego Father Christmas, who was a myth apart from Santa.

The author of that essay contends that the prevalence and persistence of these holiday customs throughout the entire historical record of the West, and likely even earlier into Indo-Aryan prehistory, speaks to their profound importance to the European psyche. What are some of the major themes that emerge?

First, the return of light. The winter solstice marks the longest and darkest night of the year, after which the life-giving Sun, the Oak King, begins his return — a fact of enormous significance to a pre-industrial and agricultural people. This return of light in the darkness is commemorated by the prevalence of candles, light displays, and brightly-lit trees. The ubiquity of evergreen garlands and wreaths also speaks to this theme, representing the growth of vegetation in an otherwise dormant and cold season. The metaphysical import is also clear. In Christian belief, the world was shrouded in darkness after the Earth and mankind fell under the dominion of Satan. The Christmas festival celebrates the birth of Christ, the Light of the World, who will put an end to Satan’s reign and usher in a kingdom of eternal light.

This is related to another theme of this holiday, that of the Golden Age. As mentioned above, Saturnalia was a commemoration of Saturn, who was held to have presided over a Golden Age on Earth; his festival was therefore viewed as a temporary restoration of this happy period of human history. Christ as well entered the world to restore the unity and purity that existed in primordial man, to heal the wounds wrought by pride and self-will. Many of the shared themes of these holidays — good cheer, feasting, gift-giving, charity, avoidance of labor, wassailing, the erasure of social distinctions, and a general atmosphere of merriment and goodwill — are traits that we can readily associate with a Golden Age. Moreover, Christmas’ special association with childhood, discussed in the beginning of this essay — its celebration of the birth of a child, the role of Santa Claus as a gift-giver to children, the general happiness and wonder of the season that appeal to the child in all of us — points to another feature of this Golden Age: In children, we see the closest approximation to the innocence, purity, and simplicity of primordial man, a gift to be treasured as well as a model for adults.

Thus, in conclusion, I would like to encourage all Men of the West scattered throughout the globe, whether pagan, Christian, or pantheist, to celebrate this holy season in earnest. Take some thought for its meaning and the ancient traditions that surround it, though they have been watered down and overshadowed in recent years by consumerism, sentimentalism, and degeneracy. Learn about and adopt some of the ancient customs, games, and foods that were once embraced at this time of year, and restore the prolonged celebration of merriment in your family and community. This period of twelve days, taking place at the darkest time of the year, was among the most sacred of times to our ancestors — and for good reason. With it, we celebrate the return of our life-giving star, the birth of the true King, and the coming restoration of the Golden Age for ourselves, our children, and our people.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[26]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[26]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.