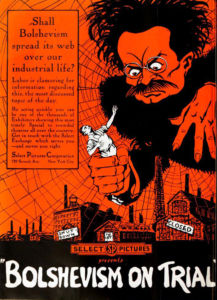

Bolshevism on Trial

Posted By Beau Albrecht On In North American New RightThe prolific writer Thomas Dixon wrote a number of books that were adapted into early cinema. The most famous was The Clansman,[1] [2] adapted into the iconic movie The Birth of a Nation. He often wrote about Fraternity Tri Kappa and the Radical Reconstruction. Another frequent topic was the Red Menace. Along those lines was his book Comrades.[2] [3] This became the silent film Bolshevism on Trial, also called Shattered Dreams.

Back in the early days, Communism was the way of progress and the nascent USSR was a workers’ paradise, at least according to lots of the usual types in the media. (Accurate reports of tremendous political violence and mass starvation had emerged, but that didn’t stop plenty of other journalists from denying the facts and praising the Soviet Union to the skies.) The emerging ideology that promised so much did make a splash in certain circles. It’s understandable that there was some excitement about it. Then there were those who weren’t quite buying all that. Bolshevism on Trial makes the case for them.

The film was released in 1919, ten years after the book upon which it was based. Interest in the production was surely spurred by the October Revolution of 1917. (Some of the billing calls itself “the timeliest picture ever filmed.”) Still, the Cold War wasn’t on the horizon yet. Therefore, much as with Red Salute [4], it’s about Communism as a concept rather than the military and spy dramas that came later on.

Our story opens in the home of a wealthy WASP family. The intertitle introduces the paterfamilias as:

Colonel Henry Bradshaw, a brain worker, whose inventions have

- increased the comfort of his generation

- created work for thousands of employees

- brought wealth to himself

This is what our CEOs used to be like; how about that? The ones like Henry Ford are getting to be a rare breed. Lately, executives still bring wealth to themselves, but all too often operate sweatshops in the cheapest labor market they can find. Over the years, goodness knows how many inventive WASPs like Colonel Bradshaw got pushed out of the companies they founded thanks to boardroom shenanigans or leveraged buyouts. In the book, the family name is Worth, which surely is symbolic, and contrasts with another name featuring prominently in the book: Wolf.

He reads the newspaper, noting an item, “Society Girl Joins Reds.” It’s about the heiress Barbara Alden’s upcoming appearance at a radical meeting where they’re making plans to buy an island in Florida. (In the book, the commune is to be located in California, apparently on one of the islands due west of Los Angeles.) He glowers and — if my lip-reading is on point — exclaims, “Damn it!”

His son Norman arrives, and they discuss the newspaper item:

“But the girl’s gone crazy — if these long haired talkers got control of the Government, they would ruin my business and throw my men out of work!”

“Lots of things are wrong in our social system, Dad, and maybe Barbara sees further than we do!”

Uh, oh . . . Then we see Barbara working on her lecture notes. Much like Obama in our times, she wants to spread the wealth around:

We should feed and shelter the unfit and the unfortunate! They cannot be left to starve and die.

All workers should unite to produce enough so that the surplus of the strong may be distributed to the weak.

The nobility of human nature should be challenged.

We all know where this kind of thing goes, now don’t we? Show a little too much kindness, and there’ll be generation after generation of welfare queens freeloading off of productive taxpayers to produce more of the “unfit and unfortunate.” We feed, they breed.

The scene cuts back to the Bradshaw residence. Norman’s sister Nancy drops in just before their father heads outside. (She’s played by Valda Valkyrian, who is about as smoking hot as one would expect from such a name.) A butler brings in the mail, and it turns out that Barbara wrote to Norman, canceling a lunch date but requesting to meet elsewhere and bring a doctor. Rather than taking offense at being flaked on, he decides he’ll go to the pinko meeting, and Nancy wants to attend, too.

The chief radicalinski is Herman Wolff, who looks rather like the love child of Bela Lugosi and Richard Nixon. The intertitle states, “Wolff’s type has emerged in every social revolution: the strong man who exploits the sincere ideals of less aggressive people, turning social discontent to his own advantage.” (A century later, these characters are still quite common, of course.) He gives Barbara a brief pep talk.

A little later, his wife Catherine notes, “Barbara’s unconscious motive is a motherly sympathy for those unable to care for themselves.” Of course, this is a spot-on assessment of those whose psychological makeup is so often exploited and turned toward pathological altruism [6]. As for Catherine, in the book, she’s described as an “affinity-wife.” Unwisely, she had abandoned her real husband and children, monkey-branching to this two-bit agitator.

Barbara is seen at a tenement tending to some young ragamuffins, and then visiting the sick. Norman drops by, bringing the doctor as requested. A brief political discussion follows. Then it cuts to Wolff and company persuading Barbara to convince her wealthy friends to help fork over the dough to buy the island.

Other People’s Money

The big meeting begins. There appear to be about 200 attendees. Herman Wolff himself plausibly presents as a garden-variety Kraut, but about half in the audience have an (((ethnic))) appearance. According to what I’ve heard of the Communist Party of the United States’ demographics around then, that much was historically accurate. The crowd is well-dressed; there are more bowties than a Nation of Islam rally, and not a single proletarian in overalls or a grimy smock.

Then the background music riffs on the intro for the “Hymn of the Soviet Union” as Wolff announces the fundraiser for “the one spot on this Earth where we can be free with a real freedom.” This is to be Paradise Island, equipped with a winter resort. (The filming location was a lavish hotel in Palm Beach, now defunct.) This, and the promise of fancy parties, piques the interest of the limousine Leftists. Comrade Barbara gives a short speech with some sugary platitudes. She smooths things over when someone heckles Wolff about not pitching in himself. Then Norman gets caught up in the excitement and pledges to fund the venture. The pinkos are ecstatic.

The kid doesn’t have the dough himself, of course. His father isn’t too amused when he asks for it, to say the least. His sister intercedes, melting Daddy’s heart enough to promise, “Don’t worry, dear. He’ll get his island — and a lesson along with it.” This bears some resemblance to a scene in Atlas Shrugged in which Hank Rearden pledges a lavish donation to some Leftist outfit, trying to make his sniveling punk of a brother happy. He replies with remarkably tepid thanks, and wants the donation in cash to conceal the source: “You see, Friends of Global Progress are a very progressive group and they have always maintained that you represent the blackest element of social retrogression in the country . . .” Precious, isn’t it?

The People’s Democratic Republic of Paradise Island

[7]

[7]You can buy Trevor Lynch’s Part Four of the Trilogy here. [8]

Saka, their Indian gardener, played by Chief Luther Standing Bear of the Lakota (not to be confused with Chief Standing Bear of the Ponca), is recruited to go with Norman. His dialogue is rather like that of Tonto from The Lone Ranger. “Me tame Indian — no like-um Red — but like-um Mister Norman — me go.” So he wasn’t that kind of Red man, but was up for the adventure anyway. Norman’s chauffeur, a rough character, is also game.

After the boatload of limousine Leftists disembarks, they enter the posh hotel, wearing their suits, fancy dresses, and fine hats. (The ladies are in belle époque fashion; it’s a little too early for flappers.) They clamor for the choicest room accommodations. Norman is lauded for making this possible. So far, so good. Then privately, Wolff says to his wife, “We’ll have to elect Bradshaw as Chief Comrade — but there’ll be enough trouble in a month, so this mob will recognize its real leader.” Uh, oh! Plotting to push him aside so soon? Then the red flag is hoisted over the hotel.

Norman, who indeed gets elected Chief Comrade, surveys their job skills to determine work assignments. The first problem the kid has is that there are 94 applicants for one assistant manager position. Obviously, then, the only practical trade that nearly half of these radicalinskis know is telling other people to work harder. Then there are 16 would-be professional actors, but Norman tells them there won’t be any arts and sciences until the local economy gets to the point that it can support them. He remarks, “Not one offers to wash, cook, or plow, build sewers, or weave cloth for our clothing.” Oops! “We need heroes and heroines of labor. Who will volunteer?” None of the bourgeois Bolsheviks say a peep. As Wolff suggests to him, he announces that there will be work assignments, and slackers will be disciplined.

Widespread kvetching results. In the aftermath, Wolff confides, “Once rid of Bradshaw, the island can be the basis of world-wide operations.”

They throw a party, despite an impending food shortage. While most of the pinkos and pinkettes are dancing in the ballroom, the men running the power plant — finally, some people who actually look like proletarians — decide to cut the electricity. Norman drops by, and they inform him that they’re sick of working only for room and board. He agrees to pay them with his own money. Soon after, the chef and kitchen staff demand payment, arguing about who should get more. Then the gardeners come with their hands out. Finally, about three dozen more come to mob the mini-Politburo, but are turned away.

Now they’ve done it

At a special assembly, Comrade Bradshaw is deposed and Comrade Wolff takes over. He gets a Bill Gates smirk [9] on his ugly mug. (In The Birth of a Nation, this is a signature shtick of the Thaddeus Stevens character.) Immediately he announces, “Comrades, we can spread the Red Brotherhood over the world and come to power and riches.” Cool deal: more Other People’s Money! Every socialist utopia needs plenty of that. Then, “We will organize the Red Police to deal with those on the island who disagree with us.” He also decrees atheism. Finally:

The marriage laws will no longer bind us. Divorce will be on application. The State will raise the children. I promise absolute freedom.

That much was joyously received, unlike the Red Police proposal.

On that note, Norman is arrested. He had stepped aside gracefully, but Wolff wants to force him to hand over the lease. The chauffeur informs Saka, who had flown the coop and set up a teepee elsewhere on the island. He takes off in a canoe and sends a telegram to Norman’s father. Comrade Wolff dumps his dutiful but slightly frumpy wife and sets his sights on Barbara. The chauffeur helps Norman escape from captivity. Colonel Bradshaw manages to arrange a trip on a small troop transport. (Surely he found a Navy officer in a cooperative mood.) Just as sailors charge onshore, Norman comes to his girlfriend’s rescue and clobbers Wolff.

The Navy captures the hotel; it’s rather like the invasion of Grenada in miniature. Father and son reunite. Now he approves of Barbara, who by now also has had some second thoughts about the glories of Communism. Comrade Wolff is arrested, whose real name turns out to be Androvitch. (In the book, he’s shot while resisting arrest; the film has some other changes to the ending as well.) His wife looks pretty miserable, probably unaware that her husband is a spy. The red flag is taken down, replaced by the American flag.

Life imitates art

[10]

[10]Courtesy of Stonetoss [11]

Although the movie is a little over a century old, it certainly predicted a lot. First of all, given all the middle managers and artsy types, along with the trustafarian protagonists Norman and Barbara, apparently their Dictatorship of the Proletariat in miniature actually turned out to be so bourgeois that it hurts. This is supremely ironic given Marx’s pointedly dyspeptic opinion about that social class. A century later, and nothing has changed. Pinkos have become more bougie, if anything. Once upon a time, some Reds actually were factory workers — which was their target demographic — but I’ve never met any.

The “free love” business had a historical parallel. The early Soviet Union did conduct a social experiment [12] along those lines. (Early on, according to some sources, there even was some discussion about nationalizing women, but fortunately that didn’t go anywhere.) Their libertinism initiative turned out to be an unmitigated disaster. When Leftists cancel a dodgy social experiment, instead of doubling down on it as usual, this is a sign that things really went off the rails. As I wrote in Deplorable Diatribes [13]:

Throwing out the rule book is a good way to find out why the rules were necessary. Again, the government put a stop to the failed experiment. The Soviets figured out the hard way that this stuff doesn’t work, so you can’t promote it in your own country.

When they got their fingers burnt and the free love party was over, Wilhelm Reich complained bitterly [14]. He blamed the Soviet public for giving up their rights to unlimited cummies. Apparently he was under the impression that the people had any say in the way the USSR was run. He had better luck with being an early promoter of the Sexual Revolution in the United States.

Although fictional, the miniature Soviet Socialist Republic off the coast of Florida does bear some resemblance in its basic concept to Tofudishu [15], the carbuncle that sprouted in Seattle during the Vibrancy of 2020, better known as CHAZ/CHOP. However, things turned out worse for the self-styled Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone. There, the Other People’s Money was obtained by shaking down local businesses, hardly different from a Mafia protection racket. The smelly Leftists wouldn’t have had a prayer of turning it into a functional, independent planned community even if someone had donated a factory or a 160-acre farm to provide legitimate revenue. For that matter, it wouldn’t have lasted an hour if the local authorities hadn’t tolerated the lunatics running the asylum. Ultimately, their overindulgent patience ran out because of Tofudishu’s intolerable crime rate, which included murder.

Finally, the radicalinskis in Bolshevism on Trial couldn’t get their productivity sufficient to make the colony self-sustaining. The film only touches on that briefly. Still, this much is rather prophetic; predicting the chronic shortages and bare shelves that characterized Marxist countries.

Moreover, the repression depicted turned out to be quite accurate at a time that Soviet Russia was only two years old and was being talked up as a workers’ paradise by comsymp journalists. To make it any truer to life, the filmmakers would’ve had to show a mass grave with dozens of corpses. Wolff’s ambitions of spreading the Revolution far and wide also seem to parallel those of figures like Leon “General Buttnaked” Trotsky. There’s little wonder why several of the movie posters looked like caricatures with his bouffant hair, specs (usually), mustache, and nasal physiognomy.

The irony here is that with only a couple hundred or so participants, Bolshevism on Trial was socialism played on easy mode. Communal arrangements actually have worked in the long-term, but only for limited, tightly-knit communities which don’t have expectations of high living. The best examples are monasteries and primitive tribes. In the US there was a good bit of interest in communes during the 19th century, generally along religious or philosophical lines, and some lasted for decades. The track record during the 1960s was worse; communes created by lazy hippie burnouts and other counterculture lotus-eaters typically became public nuisances and folded quickly. For small-scale socialism to work, it requires a reliable revenue source as well as an exceptional amount of cohesion and discipline. That means the participants are fully committed to the arrangement, treat each other as family, and exclude slackers who will be deadweight and cause resentment.

On the other hand, attempts to scale up socialism never delivered the promised prosperity. For one thing, central planning gets very unwieldy with an economy the size of a country. (Obviously, that’s orders of magnitude more complex than managing a monastery’s wine and cheese production.) Worse, Marxist countries tend to turn into despotic hellholes. This is an inevitable result of trying to use coercion to wallpaper over the chasm between the realm of pure theory underpinning Leftist ideology [16] and the way the real world actually works.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[17]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[17]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.

Notes

[1] [18] The Clansman: A Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan (New York: A. Wessels Company, 1907).

[2] [19] Comrades: A Story of Social Adventure in California (New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1909).