Blacks in Tennessee Williams’ Works

Posted By Andrew Hamilton On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled2,002 words

In a recent essay [2] about playwright Tennessee Williams and Greek-American director Elia Kazan’s flagrantly anti-Southern motion picture Baby Doll (1956), I observed in passing that blacks are present as furniture, but there is no major subplot involving them. The film’s racism is expressed through its utter contempt for Southern whites.

The following are three examples of fleeting black presences in the film.

While protagonist Archie Lee, the white cotton gin owner whose young wife refuses to have sex with him and repeatedly insults him in public, impatiently waits in his car for Baby Doll to finish dressing for a trip into town, three old black men are lounging nearby.

Archie Lee smiles jovially at one of them sitting off to the side. Poker-faced, the man does not acknowledge the gesture. (In truth, Archie Lee is weak, not kind.)

After Baby Doll emerges from the house, the other blacks, seated against a nearby tree, grin, then roll on the ground in silent mirth as she puts down her husband in front of them.

Archie Lee glares at the duo impotently without saying a word, causing their laughter to cease immediately, and the grins to be wiped from their faces.

The white man looks ridiculous not only to his wife and a superior Sicilian outsider who runs all the local cotton gin owners out of business and eventually steals Baby Doll from him, but even to no-account blacks who openly mock or ignore him.

At a local meeting, the Sicilian is showered with praise by a Senator for his business acumen and boosting the local economy. Lower-class whites in the audience jeer, suggesting that next, the Senator will be praising “niggers.”

In 1956, as today, the choice of that word was intended to demonstrate the narrow-minded bigotry of Southern whites — which, the movie hammers home, extends to foreigners (including, by implication, Greeks like anti-Anglo immigrant Communist Elia Kazan).

In a third scene, Archie angrily storms out of his house. Turning the corner, he comes face-to-face with one of his black employees. He leans against the wall beside the man for a moment.

“When we gonna start ginnin’ out some more cotton, Mr. Archie?” the employee asks.

Archie doesn’t reply, but removes a whiskey bottle from his pocket, takes a swig, and hands it to the black man, who drinks from the same bottle before handing it back. Archie tucks it away again before leaving without a word.

Archie Lee’s behavior toward blacks is not “racist” in today’s mass media sense in these scenes. Anglo whites are mocked, denigrated, and degraded mercilessly throughout the film, but a Sicilian, not blacks, is the object of bigotry. It’s the same anti-white movie/TV/Internet sermon we’ve heard six million times before, but with a twist.

Blacks are shunted to the side and ignored. The few times they are shown, they are not presented as objects of worship.

That is, they are not today’s puffed-up, violent ghetto thugs, gang members, unprosecuted hate criminals, rioters, murderers, or glamorized Left-wing celebrities, athletes, politicians, “civil rights leaders,” singers, or advertising models lionized by screen, television, the Internet, video games, rap music, interracial porn, fawning academics, and politicians.

Nor, for that matter, are they the saintly Negro caricatures of yore depicted in A Raisin in the Sun or To Kill a Mockingbird.

Instead, blacks are second-class citizens, not superior or threatening in any way. They range from altogether unprepossessing to unattractive, as their appearance and behavior graphically illustrate. Baby Doll probably could not be screened today for that reason.

So overpowering was the film’s anti-white racism that these facts escaped me at first. Yet, they are clearly anomalous.

Blacks in Williams’ Plays

I began to wonder about other Tennessee Williams plays, such as A Streetcar Named Desire and Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. I couldn’t recall blacks playing central roles in them, either. Did Tennessee Williams focus on blacks at all?

To the best of my knowledge, blacks might have had a peripheral presence in his Southern settings, but as in Baby Doll they seemed to play no meaningful roles in the stories.

It appears that my vague impression was correct. One anti-white academic noted the “apparent absence of African American voices” in Williams’ work, combined with predominantly “unflattering images”:

In many of the Williams plays set in the South — Battle of Angels, The Glass Menagerie, Summer and Smoke, The Rose Tattoo, and Suddenly Last Summer — African American characters do not appear in the plays at all. Although C. W. E. Bigsby has remarked upon this absence — “scarcely a black face is to be seen in Williams’s South” — Bigsby directs his attention to the more visible presence of the bigot [emphasis added] in plays such as Orpheus Descending and Sweet Bird of Youth to illustrate Williams’s “contempt for the [white] racist.” The attention that bigots such as Jake Torrance and Boss Finley attract to themselves nevertheless obscures from sight and attention a group of African American characters whose menial roles, limited dialogue, and disparaging names (or namelessness) all attest to their marginal status in Williams’s dramatic world.

This perfectly describes Baby Doll. Williams’ works are profoundly anti-white, but not pro-black. Though little-discussed, this becomes conspicuous once you are aware of it. It isn’t immediately apparent due to the intensity of the anti-white racism.

The few African American characters who appear on stage in Williams’s plays are relegated to peripheral positions, acting as servants or in subservient roles, for example, Lacey and Sookey in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Fly in Sweet Bird of Youth, and the hotel porter in The Last of My Solid Gold Watches. If these characters speak at all, it is to say only a few lines (as does the [unnamed] “Negro Woman” in A Streetcar Named Desire). — George W. Crandell, “Misrepresentation and Miscegenation: Reading the Racialized Discourse of Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire [4],” Modern Drama (Fall 1997).

[5]

[5]You can buy Kerry Bolton’s Artists of the Right here [6].

Curiously, despite this, all-black and multiracial productions of Williams’ plays, in which white actors are replaced by non-whites, have become a popular cottage industry.

The racist academic says the only exception to this rule about blacks is the character “Chicken, a man of mixed racial heritage,” who plays a major role in The Seven Descents of Myrtle (1968, a.k.a. Kingdom of Earth). Despite the play’s marginal importance, it is at least suggestive in light of Williams’ phenotype, as I will discuss shortly.

The characters, setting, and plot of The Seven Descents of Myrtle involve the usual Southern Grotesque nonsense. The Jewish Broadway production closed after just 29 performances, and Jewish director Sidney Lumet’s Hollywood version, called The Last of the Mobile Hot-Shots (1970), also flopped despite a tantalizing X rating.

If Not Negrophilia, what did Tennessee Williams Supply that American Elites Wanted?

What did Jews want or get from Williams in return for artistic and cultural adulation?

First and foremost, they obtained racial defamation of the South, and through it, of normal whites everywhere. The racial animus is pretty intense.

Beyond that, Williams vigorously promoted degeneracy.

Culturally harmful themes were more overt in his Broadway plays performed for elite New York audiences than in film adaptations made for the public. The homosexuality in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof was more explicit in the play for Jewish and other Left-wing theatergoers than it was in the 1956 film distributed to American audiences. This was due in part to the residual effects of the production code.

A homosexual house Negro writing for the New Yorker [7] asserted in a 2014 review of a Williams biography written by John Lahr, son of Jewish entertainer Bert Lahr (real name Irving Lahrheim, the Cowardly Lion in The Wizard of Oz):

The narrow, restrictive world that Truman and Eisenhower wrought was just a version of the kind of repression that Williams had grown up with; his work spoke to those who could not fit within the parameters of all those neat lawns and white picket fences and solid heterosexual values. . . . The world was correct, pious, duplicitous Edwina [the playwright’s strait-laced mother], and Williams wanted to queer the world.

That’s another thing Williams helped achieve.

The former pro-white underground magazine Instauration featured the playwright in its monthly “Primate Watch” department from time to time. The August 1986 issue provided some insight into his ethics:

Writer YUKIO MISHIMA may have been a Japanese traditionalist in most respects, but not in his predilection for blond-haired men. TENNESSEE WILLIAMS met Mishima through TRUMAN CAPOTE. The two went “cruising for young blonds,” recalled Williams. “Baby, that was his ticket.” Williams also met FIDEL CASTRO, through the partly Jewish writer, KENNETH (Oh! Calcutta!) TYNAN (“known as Lord Slap-Slap because he was always beating up women”). During a deep political discussion with [Jew] ABBIE HOFFMAN [8] who symbolized “the movement” in Williams’ besotted mind — Williams raved about his good friend, Fidel:

What a beautiful man! He embraced me! Uhhh, this powerful man, this revolutionary said it was an honor to meet me! What a gentleman. I am certain he does not know what is going on in his prisons [Williams had rampant homophobia in mind] or he would instantly put a stop to it!

Besides bigotry, that’s the kind of thing Williams served to those seated at the table of America’s cultural elite.

Was Williams a Mulatto?

In my review of Baby Doll, I quoted Establishment sources saying that Williams was “a descendant of hardy East Tennessee pioneer stock,” and highlighted his intense hostility to “his own native Southern stock.”

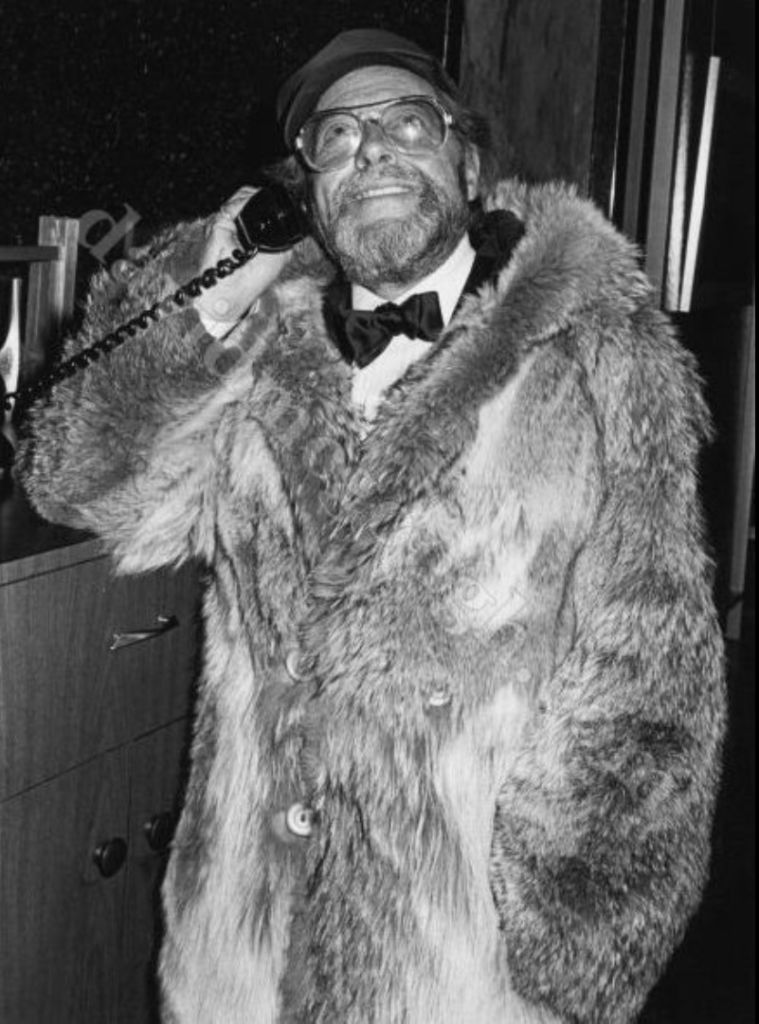

I’d seen photos of Williams, but hadn’t looked at an array of them. Doing so gave me pause.

It’s been rumored that FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, born and raised in Washington, DC, might have had black ancestry. No proof of this has surfaced, but rare early photographs of the budding secret police boss show the possibility more clearly than later ones.

Such images don’t prove that Hoover was part-black, though the rumors might have begun among people who had known him personally when he was young, rather than merely through photographs. Gore Vidal, also raised in Washington, DC, is among those who mentioned the rumors.

Several photographs of Tennessee Williams suggest a similar possibility.

[10]

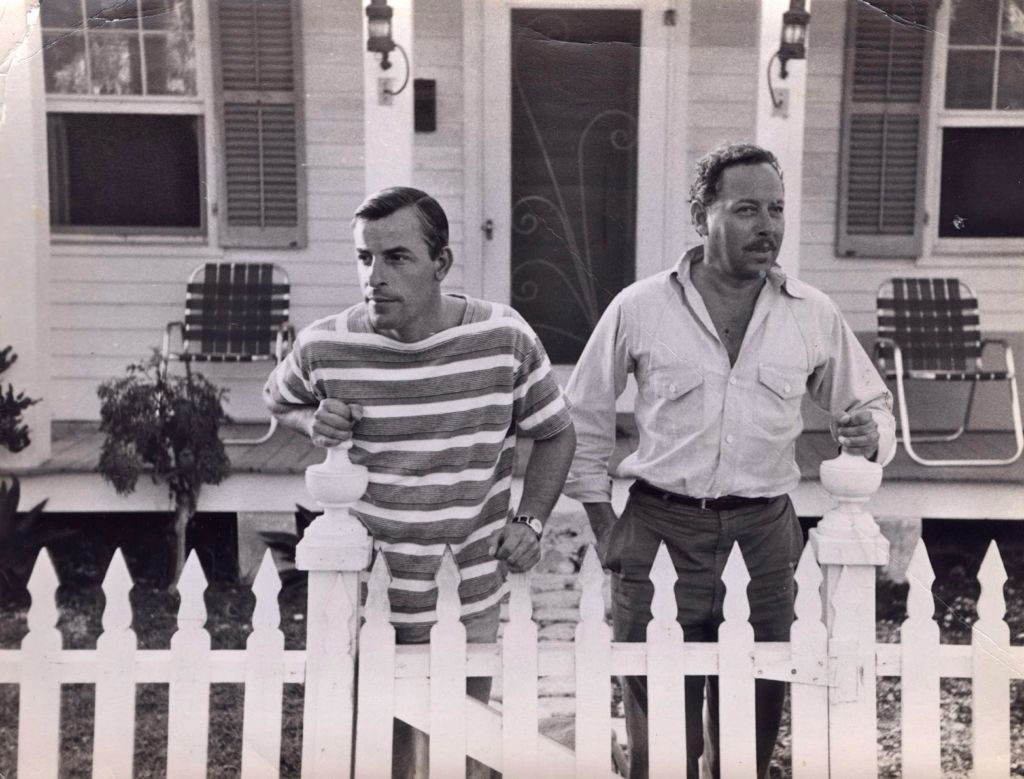

[10]Three ethnicities: Theatrical producer Irene Selznick (daughter of Jewish MGM mogul Louis B. Mayer); 36-year-old Tennessee Williams, pointing; and Turkish-born Greek immigrant Elia Kazan on the set of A Streetcar Named Desire, New York City, 1947.

Not all photographs of him look like these. A picture of Williams at age 5 [13] doesn’t. I haven’t personally read anything proving, or suggesting, that he had mixed-race ancestry. Nor, for that matter, have I seen anything detailing, or purporting to detail, his white ancestry. Whether this issue has been raised or reliably elucidated in any books, biographies, or articles, I have no idea.

The most commonly available Establishment source [14], which unfortunately is no beacon of truth, integrity, or reliability, says only that Williams was of “English, Welsh, and Huguenot” (presumably French) heritage.

If Williams did have some black ancestry, it would be desirable to know what mix he was, and what effect (if any) it had on the intensity of his anti-white prejudice and the limited attention he paid to blacks in his work. Balancing this, it must be kept in mind that, for a century now, there have been thousands of white-hating whites. (And thousands of non-white bigots as well, including Jews and part-Jews.)

Homosexuality played a significant role in Williams’ renegadism, considering the prominence he gave it, openly or camouflaged, in his work. But for a renegade Southerner at that time, his comparative silence about blacks is peculiar.

If he did have meaningful black ancestry, we could at least classify him as “not one of us,” genetically speaking, and focus attention on the racial pathology characteristic of genuine whites.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[15]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[15]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.