The Eternal City, the Ruined City, & the Battle of Cannæ

Posted By Kathryn S. On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled [1]

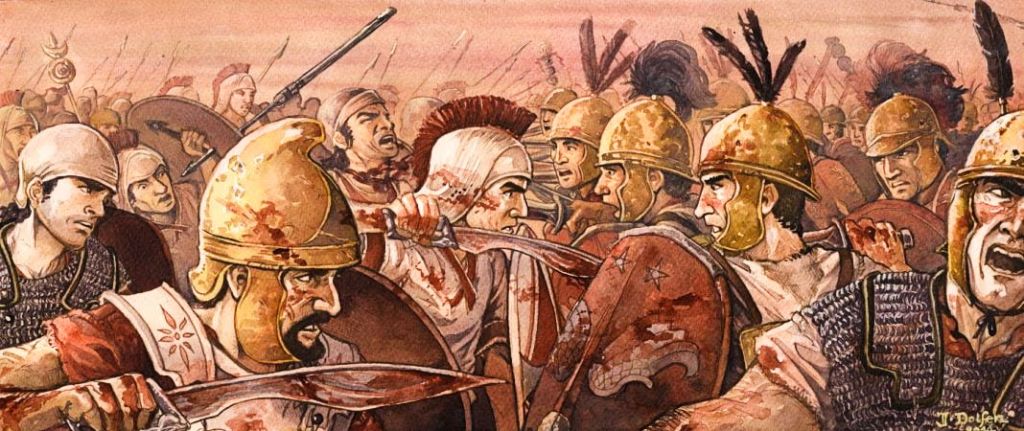

[1]Illustration from J. N. Dolfen’s Darkness Over Cannæ [2] (2020).

7,819 words

And I have in mine owne bowels made my grave, That of all nations now I am forlorn, “I was that citie that the garland wore . . . delivered unto me By Romane victors, which it wonne of yore; Though not at all but ruines now I bee, And lie in mine owne ashes, as ye see.”[1] [3]

Scipio’s Tears, Scipio’s Oath

There was that memorable scene, played again and again in every age. That vision of ruin at the moment of triumph. So did Napoleon later look out on the vale leading down to the Olomouc Road and see that the hunt after honor had reared a trophy for “devouring death.”[2] [4] So great a victory born of genius and long labor pains, as if these glory days would forever with him remain; as if it all might not vanish into cloud, might not sink beneath the tomb. As if he might wear Augustus’ mantle for eternity, and would not Cæsar’s laurel crown, like a man of the hour. And it was here near the southern beaches of Mare Nostrum that Scipio Æmilianus (henceforth Scipio the Younger) looked as a conquering captain upon the death throes of a once-mighty imperial foe.

The city of Carthage burned. As usual, Rome’s revenge had not been swift, but it was inexorable, for its people worshiped a god of revenge called Mars Ultor, meaning: “Mars, who has the last word.”

When his Greek slave Polybius, once his tutor and now his chronicler, turned to his master, he saw Scipio weeping for his enemies. After being wrapped in thought for long, and “realizing that all cities, nations, and authorities must, like men, meet their doom; that this happened to Ilium, once a prosperous city, to the empires of Assyria, Media, and Persia, the greatest of their time, and to Macedonia itself, the brilliance of which was so recent,” he began to quote from the closest thing to the Roman bible: “A day will come when sacred Troy shall perish, and Priam and his people shall be slain.”

And when Polybius asked him what he meant, “they say that without any attempt at concealment he named his own country,[3] [5] for which he feared when he reflected on the fate of all things human.”[4] [6] It is this with which all philosophy must grapple. Scipio the Younger in 146 BC and at the conclusion of the great series of Punic Wars that had consumed the last century of Rome’s obsession, saw not one ruined city, but three. According to old lore, Rome’s origins began with the sacking of Troy. Its fleeing prince, Æneas, journeyed far, stopping for some time at Carthage, the African kingdom of Queen Dido, whom he loved, then spurned. For his ultimate destiny lay not in the arid plains, but in the green hills of Italy, where he founded a new city from the ashes of Priam’s Troy. And just as Troy had to perish for the sake of this country’s birth, so did Carthage collapse now for the sake of this country’s youthful preeminence — for control of the “world,” and for the right to raise up kings as vassals.

So there was, of course, another city besides ruined Troy and Carthage that Scipio saw, perhaps more clearly even than the former that was past and the latter that was present and before the very eyes of his company: the Eternal City of Rome. That place that has always come to the European mind when he has heard: “city ruins.” He has envisioned the dust of Cæsars and coliseums and the ruin-loving Elderberry guarding the way to the underworld labyrinth of catacombs. A paradox of the hourly and infinity, the ephemeral and immortal in one compression, as if overlaid by the sediments of time at a single spot and during this singular moment — the moment when prophecy got the better suddenly of a hardened warrior’s emotions. He could not know that Rome would be (peacefully and otherwise) invaded by the cultures, migrants, religions, philosophies, and objects of the east proceeding from the vast extension of lands that the Romans were continually conquering. He could not know that in less than one hundred years, Rome would transform from metropolitan republic to cosmopolitan empire; that god-kings would confer on aliens the title of Roman citizen; that arenas would be built using Jewish treasure. But somehow, he did know. On foreign soil “he named his own country.”

The imagery of ruins and ruined cities have the power to move us because they symbolize the fall of man in general, and the fall of a certain race, or people, in particular. The fate of all their works and days. When victors have laid low their enemies, sacked their towns, and burnt their temples, a deeper undercurrent of foreboding has always belied the superficial gaiety that has accompanied conquest. Because the cities they had razed were no longer recognizable, they could have stood for any city destroyed by violence, or the ravages of time. The past, present, and future became one in these murdered landscapes. Their levelled homes recalled a time before there existed the streets above which their castles once rose, when the seven hills of Rome were simply seven rude mounds.

For Ernst Jünger twenty-one centuries later, the same would be true. There on the Western Front, he gazed from “the lonely hill on the road to Ransart” where the eye “could travel for miles over the ruined” villages. Further back were “the faint outlines of Arras, the forsaken city,” turned to waste and overgrown fields. “Only here and there the smoke of a shell wavered up, as though propelled by a ghostly hand . . . The face of the earth was dark and fabulous, for the war had expunged the pleasant features of the countryside and engraved there its own iron lines that in a lonely hour made the spectator shudder.” No pacifist himself, even Jünger admitted that “the soldier who walks among the ruins of a place like this and thinks of those who lately lived their peaceful lives there, may well be overtaken by sad reflections.”[5] [7] A soldier is comfortable with the immediate contingencies — the needs, the means, of battle. He is less comfortable with looking overlong at the aftermath and into the far-reaching blackness of tomorrows. Such was the future of all cities, the conquerors knew. Even — especially — their own.

[8]

[8]You can buy Kerry Bolton’s Artists of the Right here [9].

Seven decades prior to Carthage’s fall, Scipio’s two grandfathers, Publius Cornelius Scipio (henceforth Scipio “Africanus,” or “the Elder”)[6] [10] and Lucius Æmilius Paulus had both been locked into one of the most savage struggles of antiquity and against one of the most savagely brilliant of enemies. Africanus’ father had died fighting the foreign hordes of Hannibal Barca — the young prodigy of Carthage’s Second Punic War. Two years later, both Africanus and Paulus fought in one of the largest land battles in European history. Rome’s entire army was mercilessly smashed, and Paulus — one of two Roman consuls leading the field — was killed. Africanus narrowly escaped with his life. Hannibal seemed invincible, and Rome’s demise inevitable.

The young tribune and the rest of the battle’s survivors took shelter at the town of Canusium, where a noble Apulian lady provided them shelter, “corn and clothes, and even provisions for their journey.”[7] [11] As the men held a council to decide what steps they next should take, suddenly a son of an ex-consul stood and cried to his fellows that “it was useless for them to cherish ruined hopes; the republic was despaired of and given over for lost!” He and other “young nobles . . . were turning their eyes seaward with the intention of abandoning Italy to its fate and transferring their services to some king or other.” Scipio Africanus, the general destined to “end this war,”[8] [12] sprang up in a fury when he heard this treason. “Let those,” he cried, “who want to save the republic take their arms at once and follow me. No camp is more truly a hostile camp than one in which such [treachery] is meditated.” Then, he held his “naked sword over the heads of the conspirators” and uttered these words:

I solemnly swear that I will not abandon the Republic of Rome, nor will I suffer any other Roman citizen to do so . . . Whoever will not swear let him know that this [blade] is drawn against him.

The abashed aristocrats hastily gave their word and surrendered themselves to Africanus’ custody, for they were in as “great a state of fear as though they saw the victorious Hannibal amongst them.”[9] [13] Uppermost on Scipio the Elder’s mind was ensuring the future of his country. And at the fulfillment of this oath 70 years later, Scipio the Younger saw his country’s future fate playing out on the long tongue of land that led from Carthage to the sea and that reflected in Scipio’s tears its flaming ruins. At the fulfillment of an oath there followed an omen, for Fortune respects no great man.

Barcid Rage, Barcid Oath

Hannibal Barca’s rage was great, for Hannibal Barca was a great man. Just as they had swept up the two Scipios, the Punic Wars had also consumed his father’s, and then his own, life. At the conclusion of the First Punic War (264-241 BC), General Hamilcar Barca, humiliated at Carthage’s defeat and at the steep reparations his people had pledged to pay Rome, offered up a sacrifice to Ba’al.[10] [14] Then, leading his young son Hannibal by the arm, he asked the nine-year-old if he would follow in his footsteps and succeed where he had failed. Then, Hamilcar placed the boy’s hand on the sacrificial victim and made him swear “never to be a friend to the Romans.”[11] [15] Virgil’s Dido would echo this terrible oath when he imagined the betrayed Queen cursing Æneas and bidding him to

Go with the winds! Pursue Italy! Chase across seas for your kingdoms! My hope is that . . . you’ll drink retribution in deep draughts, often invoking Dido’s name. When I’m absent, I’ll chase you with dark fire! When cold death Snaps away body from soul, evil man, my dank ghost will haunt you![12] [16]

Soon after, Hamilcar died, and his war helm passed to his son, who was now determined to make Rome regret their designs in Punic Spain and Sicily. To make Rome regret her dreams of empire.

To this end, he set out to drain away the lifeblood of Æneas’ line by executing some of the most daring feats in military history. For a single person crossing from Gaul to Italy, the Alps would have seemed insurmountable, and unless one gave credence to the old tales of Heracles’ passage, “they had never yet been bridged by any route, as far at least as unbroken memory [had then] reach[ed].”[13] [17] But Hannibal marched an army of perhaps 80,000 men and 40 war elephants from Saguntum through the forbidding mountain range and into the heartland of the Italian peninsula (and in wintertime, no less!). His exact route is still a matter of contentious debate, and it was not without cost. Like mountain folk everywhere, the Alpine tribesmen who lived in these bluffs hated intruders, and they carried out constant raids on Hannibal’s troops, disrupting their progress and spooking the animals, sometimes even over the cliffs. At chosen bends, attackers rolled stones downhill and crushed the men below. They set up ambushes from the crowning heights and burned their supplies. At one point, a massive landslide blocked the way of the entire army. So, Hannibal’s resourceful engineers, in order to destroy the largest of the boulders, “piled faggots of wood around [them], setting [a] fire and keeping the pyres going” until they reached a great temperature.[14] [18] Then, the men poured their rations of sour wine onto the super-heated rocks — a process that caused them to crack and to break apart into pieces. By the time they reached flatter country, Hannibal’s epic march had lasted five months and had turned him into a demigod on the order of Heracles — from whose mighty rages mortals had once cowered. Rome was horrified.

At Trasimene and the Trebia River, Hannibal’s diminished forces routed the Romans sent to stop them. The general’s plan to isolate Rome and cause their Latin allies to defect seemed to be working. The Senate elected a temporary dictator, Quintus Fabius Maximus, to handle the crisis. But instead of seeking a decisive battle, he implemented the “Fabian Strategy”: harrying tactics that avoided head-on conflict and made the struggle one of guerrilla attrition. Angered at such a “shameful” method of fighting, the Senate dismissed Fabius and named two new consuls to head the government: Paulus, already mentioned, and Gaius Terentius Varro. Unlike the Carthaginians, Romans did not use trickery or guile to win their wars, the voices that issued from the forum declared. Hannibal had meanwhile camped near the small town of Cannæ, where he seized its large grain stores that served as a major breadbasket for southern Italy. It was a provocation Rome could not ignore, and the City raised an unprecedentedly large army to march on his position. Teenagers, debtors, and poor farmers — people who before would never have been considered for the honor of army service — were drafted into new legions. Alongside these rode hundreds of rich and famous Romans, Scipio Africanus among them, each expecting that their part in the glorious victory to come would translate into more wealth and political appointments. This force, they believed, was too big to fail.

From his base, Hannibal watched and waited. If he had his way, Cannæ would be his masterpiece.

Punic Masterpiece, Roman Massacre

And now for a dive into this iconic battle: how it was fought, what it may have looked like, and what its veterans may have experienced. As usual, Hollywood has played fast and loose with facts for cinematic effect. Fireballs and incendiary arrows, for instance, were not used in ancient warfare nearly so often as modern media would have us believe (especially not in non-sieges). Opposing armies and cavalry weren’t eager to die, nor to kill precious animals like horses during charges of folly. Huge, brutal “clashes,” as always seem to happen in medieval epic films, are largely based on fiction. Cavalry feinted, rather than slammed, into one another. Infantry might have shouted and pounded their equipment before rushing the last 30 or so yards towards the enemy. But these acts of adrenaline and anxiety would not have resulted in the front lines impaling themselves on their opponents’ spears, nor of crushing them against their shields. Insanity! Self and line-preservation necessitated that they slow and stop short.[15] [20]

Thus, it was unlikely that men ran straight into each other, for this risked them losing their own balance. And a man on the ground during a mêlée was immensely vulnerable. Attackers “began the charge at a run, but if the defenders stood or advanced as steadily to meet them, it seems that both lines checked their pace and then walked or shuffled into actual contact.” They would only accelerate their running charge if the enemy gave way before them and it was a question of “chasing and striking at their helpless backs.”[16] [21] Roman legions preferred to engage in a gradual push forward. Hand-to-hand combat was, of course, usual at the front kill-zone, but individual duels became physically and psychologically exhausting after only a few moments of sustained fighting. So, men would have engaged in these spats sporadically, or in intervals whose “rest periods” would have lengthened as the day wore on.

[22]

[22]You can buy Kerry Bolton’s More Artists of the Right here. [23]

Warfare studies have determined that before such routs and the final chapters of battle, only a small percentage of men ever actively sought to kill their foes. Most combatants were concerned with defensive measures, of staying alive — not being a hero, not winning an Iron Cross. They fought in a limited way. Another small percentage was simply unable to cope with the stresses, and they shrank from the fight altogether.[17] [24] This sort of battling would not have resulted in tremendous numbers of serious casualties, but it was stressful. Excavation of bones and contemporary accounts have revealed that hours of extreme anxiety caused by these encounters sometimes resulted in fractured jaws, so forcefully and mercilessly did men grind and grit their teeth.[18] [25] A nineteenth-century author captured this feeling when he described his advance toward enemy fire:

We heard all through the war that the army “was eager to be led against the enemy,” . . . [but] the consuming passion in the breast of the average man [was] to get out of the way. Between the physical fear of going forward and the moral fear of turning back, there [was] a predicament of exceptional awkwardness . . . The mental strain was so great that I saw at that moment [when marching forward] the singular effect mentioned . . . in the life of Goethe on a similar occasion — the whole landscape for an instant turned slightly red.[19] [26]

That said, the ancient battlefield was not entirely devoid of romance. It was traditional, for example, for Roman aristocrats to meet Gaulish chieftains in single combat between the two lines. Whether such theater occurred at Cannæ, we cannot know.

But the real killing occurred during routs, or when outflanking/encircling the enemy — when making the battle one of swift movement, instead of stasis. Indeed, ancient open-field warfare of this sort had much in common with field games like modern American football (putting aside for a moment the sport’s sad degeneration in recent decades). Formations and tactics could be more or less complex, and often hard for the enemy to “read” due both to natural, visual limitations and deliberate “screens,” or trickery on the ground. Meanwhile, it would have been easy for experienced soldiers with a “booth,” or bird’s-eye view, to see the “X’s” and “O’s” of men as they attempted to win their leaders’ objectives. But unlike sideline coordinators and “system coaches” who play at war on Saturdays and Sundays, the ancient war-game necessitated that generals lead in person and on the field of mortal danger.

At the time of the Second Punic War (218-202 BC), Roman soldiers did not look like the “classic” legionaries most people imagine when they picture the ancient Roman army: shiny, standardised lorica segmentata fitted out for an imperial force that included metal helms and cheek plates; interlocked steel greaves and/or fish-scale armor. Instead, this was a citizen army made up mostly of farmers, whose equipment depended on their individual wealth. Affluent soldiers could afford metal Montefortino helmets, bowl-shaped and perhaps decorated with a circle of purple and black feathers to exaggerate their height, steel greaves, and fuller breastplates — maybe even lower-leg armor. But the majority would have gone into battle (especially into Cannæ, an event for which an army of immense size had to be hastily raised and property requirements lowered for the occasion) with many sporting leather head-gear and haphazardly sourced weaponry. Most would have received minimal training.[20] [27]

At Cannæ, the Roman force was a soldier army, but more precisely it was a large militia of citizens and Latin allies, divided into 16 legions and these into more flexible maniples. The legions at Cannæ were abnormally large, each being allocated 5,000 infantry and 300 cavalry apiece, due to “Rome’s dire predicament.” The two consuls, Paulus and Varro were in overall command of this enormous mass of men, followed by their quæstors, tribunes, and centurions. One-third of the Senate marched or rode in this army, along with hundreds of other Roman notables.

The wealthiest members of these legions would have been those who could afford to have and keep a horse, and they formed the equites class of cavalry. The youngest and poorest would have been auxiliary velites, or light skirmishers, positioned at the front in loose lines. Immediately following them were the legions’ three lines of heavy infantry: the hestati, and behind these marched principes, then the oldest and most senior of all, triarii. Velites’ body armor was almost non-existent, and they would have carried round shields and light pila (throwing javelins). Perhaps they also came armed with bows and arrows, but at this time, Rome was not particularly invested in its archers. Ideally, hestati wore helmets and breastplates, and they fought with pila, scuta (taller, oblong shields, 2.5 feet in width and 4 feet in height), and short swords. The principes class were fitted out in mail and helms, and they used the same scuta and short swords, while the oldest triarii — only moved forward as a last resort — wore heavy armor and metal head-gear. These veterans carried the scutum, hastum (a heavier thrusting spear), and a Spanish-style short sword as well. The Roman army thus operated with brutal logic. Those less-experienced soldiers were simply more disposable than veteran heavy infantry, who carried more expensive equipment, and they were thus positioned at the front lines. The hestati who survived battle would gradually rise in status and move through the higher ranks. Those who did not survive at least protected the principes and triarii from unnecessarily risking themselves. Their sacrifice thinned the herd and developed a steely core of their peers.[21] [29]

Much of Hannibal’s army, meanwhile, was composed of mercenary-soldiers and warriors. Indeed, there was a difference between the soldier and the warrior — the one defined by his connection to “the state,” and thus to military discipline/order; the other defined by his connection to chieftains, a tribal kinship that encouraged more individual bursts of bravery. Like all great generals, Hannibal knew his army well, and he commanded their loyalty. This, in spite of it being a multinational force, which (as we at Counter-Currents know) would usually have been a weakness. It was a mixed band of Cis-alpine Gaulish warriors and Spanish infantrymen at the center. It featured a starring role for the feared Balearic slingers within his division of light skirmishers. Heavier Celtiberian and lighter Numidian cavalry were usually placed on either side. And finally, crack North African infantry were located behind and on the wings. He knew their strengths, weaknesses, and how much he could ask of each group, deploying them with timely expertise again and again. These were all battle-hardened veterans of his Italian campaigns. Most of the Roman force would have been green by comparison. Still, Hannibal was outnumbered by as many as two to one, fielding perhaps 40,000 troops to Rome’s 80,000.[22] [30]

And unlike ancient authors of the battle, it doesn’t seem to this author as if the Romans had a bad strategy. Their strength lay in brute force, the push of their heavy infantry, and their overwhelming numbers. Their weaknesses were inexperience and poorer cavalry. To deemphasize the latter and capitalize on the former, the consuls chose a narrowish field with defined borders. On one side flowed the Aufidus River and on the other rolled the hills of southeastern Italy that stretched wide to the sea. Both would negate Carthaginian mobility, and if Roman counterparts held long enough, they would keep Hannibal’s cavalry from outflanking them. The untried Romans could thus concentrate their infantry in a massive push that would break Carthaginian lines and divide Hannibal’s forces, after which they could be annihilated piecemeal. It was simple, brutal, and required the least tactical complexity. It wouldn’t be elegant, but it would win the day. Consul Varro retired that August evening, confident in his plans. Just before sunrise he hung the crimson standard outside his tent, the signal to prepare for battle. Unfortunately for Varro, Hannibal had Fortune and genius on his side. He, too, had been preparing for this epic clash, and for far too long; had surveyed the landscape for too many weeks. He’d devised a risky but brilliant series of maneuvers that he hoped would be both elegant and win the day. Rome’s advantages, he would use against them.

It would have taken hours for the two armies to assemble on the chosen field. Mustering began before light, then slowly, painfully, the troops made their way century by maniple, maniple by legion, legion by division across the river. The dry August heat and the tens of thousands of sandals and hooves clambering toward the Great Meeting kicked up vast clouds of dust, obscuring the movements of both armies. According to several chroniclers, the Romans had unwisely elected to face the direction against which the wind blew this dust into their faces and irritated their eyes. By the time hostilities commenced, the morning Sun was high and hot. Already, the men were sweating beneath their armor; already, shields and spears felt heavy in their hands.

Consul Paulus rode in front and drew his sword. “What, then, is the difference,” he asked his men, “between you and those who would see you dead?” Look there! “Opposite you see mercenaries of a dozen distant lands, brought together for one thing only: the prospect of pay.” Whirling about, he continued, “Now look at yourselves! The last hope of the fatherland, thousands of men with the same mind, all with the same goal: to preserve your families and the honor of Rome!” Those who heard no longer felt their shield burdens so heavy. “To protect them from a barbarian mob that will murder your fathers, ravage your wives, enslave your children, and sacrifice them to their cruel gods, burn your houses and farms, pillage your temples, and erase the very memory of Rome from the face of the earth! We say ‘No!’”[23] [31] The assembled cavalry roared as one. The cornicen, head and shoulders draped in wolfskin, blew three long, clear horn blasts. The velites advanced.

Light skirmishers of both armies met in the middle. Men from the isles off the Spanish coast loaded stones into their slings, then at speeds of 150 miles per hour, flung these missiles with deadly accuracy. Roman velites answered by throwing their pila, spears with a long, iron barb that gutted armor and tore at flesh. They sometimes rendered opponents’ pierced shields too cumbersome for further use. Hannibal, placing himself near the center of his infantry, spread his Gauls and Spaniards wide and thin along a convex line. These nations, “more than any other, inspired terror by the vastness of their stature and their frightful appearance: the Gauls were naked above the waist, the Spaniards had taken up their position wearing white tunics embroidered with [scarlet], of dazzling brilliancy.”[24] [33] He ordered his cavalry to attack the Roman horse on either side. The skirmishers retreated and dissolved behind the heavy foot of each army. Then, moving forward, Hannibal’s center met the might of Roman spear and shield-men. Cannæ was underway.

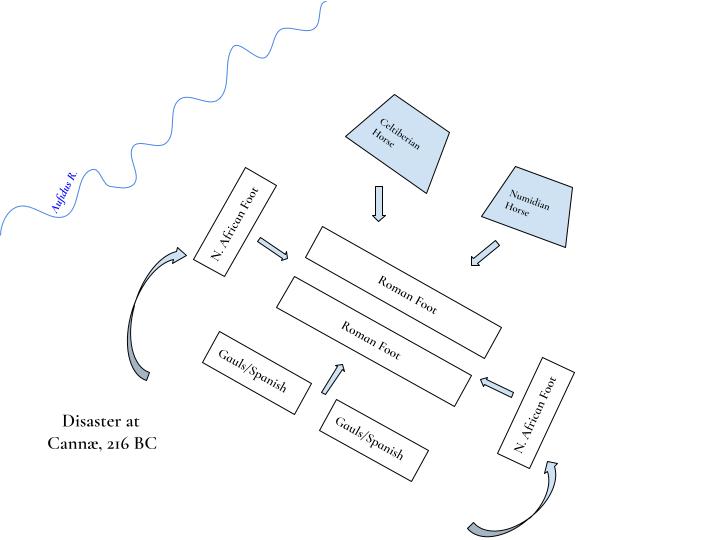

[34]

[34]A personal rendition of what the first phase of the battle might have been like, including the Romans’ simple structure and Hannibal’s more convex front.

Hannibal’s brother Hasdrubal and his Celtiberian cavalry, hemmed in by the river, engaged in none of the usual fluid advance and retreat, but collided with its Roman counterpart “in the true barbaric fashion . . . When they once got to close quarters, they grappled man to man, and, dismounting from their horses, fought on foot.”[25] [35] While the Republic’s infantry might have been overwhelming, the Carthaginian horse seriously outnumbered Rome’s cavalry. After a brief, vicious brawl, the former killed or forced the latter entirely from the field. Hasdrubal’s men pursued them, cutting down many of the fugitives, their flight made difficult by the shape of the river. Then, the victors paused to rest and regroup. Meanwhile, on the other side of the battle, the light Numidian cavalry, armed with bows and javelins, harassed the allied Roman horse with swinging feints and mobile jockeying. But there, the Republic held.

[36]

[36]You can buy Collin Cleary’s Summoning the Gods here [37].

And at the center, Rome seemed to be winning. Steadily, steadily, they pushed the Gaulish-Spanish infantry backwards. Soon, the convex shape of Hannibal’s line became concave. Officers at the front shouted encouragement to the men as fresh waves replaced those too exhausted or wounded to continue. We do not know how long this Roman offensive went on, but it likely lasted for several hours. Within the mêlée, it would have been difficult to disable an opponent with a single blow. Such feats usually required a strike to the head, a massive thrust past a shield and into a torso, or a hit that fractured leg bones. Attempting such a powerful move would have exposed the attacker to greater risk of wounding himself — a hack at his sword-arm, a ringing swipe at the head as he moved past the confines of his shield. Thus, the fighting was more likely to have featured barrages aimed at “unprotected extremities” — areas where one could injure an enemy, but not incapacitate him. The sweat, dust, slashing swords, and lack of water would have begun to sap at men’s strength.

But the Romans could taste victory. The barbarian tribesmen kept falling back, and to Roman eyes, they seemed to grow more fearful. Soon, they would break and scatter for the hills. Jubilant commanders committed the entire Roman infantry to the push and narrowed their width and lengthened their depth to effect more punching power. If tribunes saw the Carthaginian wings begin to swing ‘round on either side through the constant clouds of billowing dust (unlikely), they were not concerned, for they were committed in any case. At last, the Gauls broke. Whooping for joy, the Roman foot pursued them, and the army moved forward, losing some of their battle formation to the ecstasy of the war chase. At this point, they had no sense of danger.

Across the plain, Hasdrubal’s men had recovered from their hunt of the right-wing Roman cavalry. He reorganized them into fresh lines, then charged at the rear of the only other remaining Roman horse holed up against the Numidians. While these Latin allies had manfully held their ground up to this point, when they saw the onslaught of fierce Celts riding toward them from behind, they broke in disarray. Several hundred, Consul Varro included, managed to abscond themselves from the battlefield, but many more perished in the pursuit as they were run and cut down. Hasdrubal once again changed directions. This time, he aimed his warriors toward the unsuspecting and soft rear of the Roman legions — probably staffed with unarmored, young velites who’d drifted back through friendly lines, assuming that their part in the battle was long over. Their screams were not heard above the deafening battle music of blow-horn, hoof-drum, and sword-cymbal.

[38]

[38]The second phase of the battle: envelopment and annihilation. Hannibal’s convex line bent backward into a concave shape, allowing the wings to swing around the Roman infantry and to close in from the sides. The Roman horse having been driven off, Carthage’s cavalry turned and attacked the rear.

Suddenly, Hannibal’s Libyan shock troops, fresh and hidden at the wings till now, turned inward and advanced on either side of the Roman foot. A double-envelopment! Bewildered Romans at these hotspots would not have realized what was happening until their enemies fell upon them. Many of these North Africans had outfitted themselves in the spoils taken from previous battles, wearing Roman armor and shields. At first, they would have appeared friendly. They were anything but. Instead, they arose and began to slash at groups of legionaries who would not have had the training nor the time to mount another formation that defended their position from this new direction. All forward movement in the Republic’s army stopped cold. The vast majority of men within Roman lines would have had no idea what was going on beyond their immediate vicinities — only that they had stalled, where before they had hastened. No longer being run down, the Gauls and Spanish rallied and mounted a renewed assault at the front. The Romans found themselves completely surrounded. Tactically, the battle was over. Practically, it was far from finished.

Most military studies before the twentieth century focused on the perfection of Hannibal’s splendid battle-ballet — “something that actually went according to plan!” they enthused. “Probably better than planned!”[26] [40] Few dwelled on the decidedly un-balletic and barbaric aftermath. Following their successful encirclement, what was there left for Hannibal’s forces to do but to annihilate the still-massive Roman army — some 60,000 or more men — caught within their clutches? Modern warfare kills many, quickly, and distantly. Sometimes in an atomic minute. This is not to diminish the horrors of industrial war, for they are manifold. But in 216 BC, killing 70,000 plus men in the space of an afternoon was an altogether different experience. While historians should avoid devolving into pornography that panders to bloodlust[27] [41] (truly, the modern fixation on the worst cases of true crime is one of the most disturbing features of twenty-first century life), it is appropriate to face this reality. One saw the enemy’s eyes roll back in his skull and go dark. Every single man had to be dispatched individually and on the strength of another man’s arm, not by the impersonal motor and whirring gears of his machine. Rampage would have turned to exhaustion, then listlessness, then perhaps a final, desperate fury — on both sides. There would no longer have been any order to the Roman maniples or legions, and thus no effective large-scale resistance to the ensuing slaughter.

For a very long time, most Romans would not have been aware of what was happening, for the mass of men was too large and the dust too dense and the noise too thunderous to clearly make out the struggle occurring between enemy troops at their extremities. Instead, they began to notice the struggle to move as they were pressed increasingly, ever-more tightly inward. Men could no longer find the room to raise their swords and shields as Carthaginian rocks, spears, and arrows — rain turned to serpents, black-feathered hail tipped with steel — dove into their disordered ranks from above. The Roman foot was squeezed in a vice on all sides and “nowhere able to form a coherent and properly supported fighting line.”[28] [42] Some slid in the growing, slippery gore, fell, and were thus trampled to death. Others might have suffocated in the boiling crush, their armor becoming ovens rather than aids. Time after time the North Africans, and however many of the Gauls and Spaniards had come about, resumed their attack, surging forward into actual contact to fight a brief mêlée. They fought till they were weary and the “edges of their swords and spear points blunted through killing.” Romans admired nothing so much as stubbornness, and they persevered, many still unaware of the hopelessness of their situation. This author cannot imagine a more hellish scene.

According to Livy, Consul Paulus eventually succumbed to his injuries after leading the stiffest Roman resistance. Leaning against a large rock, he watched as tribune Gnæus Lentulus “rode by on his horse, and then caught sight of [him] sitting on a stone and covered with blood. ‘[Consul],’ he cried . . . ‘take this horse, while you still have a little strength remaining and I can attend you . . . Make not this battle calamitous by a consul’s death; even without that there are tears and grief enough.’” To this plea Paulus answered, “All honor to your [courage]! But waste not in unavailing pity the little time you have to escape the enemy. Go, and tell the senators in public session to fortify the City of Rome and garrison it strongly before the victorious enemy draws near.” Continuing to perform his role as leader, he instructed Lentulus to “in private say that Lucius Æmilius [Paulus] . . . now dies remembering his [duty] . . . let me breathe my last in the midst of my slaughtered soldiers.” Whilst they were speaking, “there came up with them first a crowd of fleeing Romans, and then the enemy, who overwhelmed the consul, without knowing who he was,” and killed him amidst a storm of steel missiles.[29] [44]

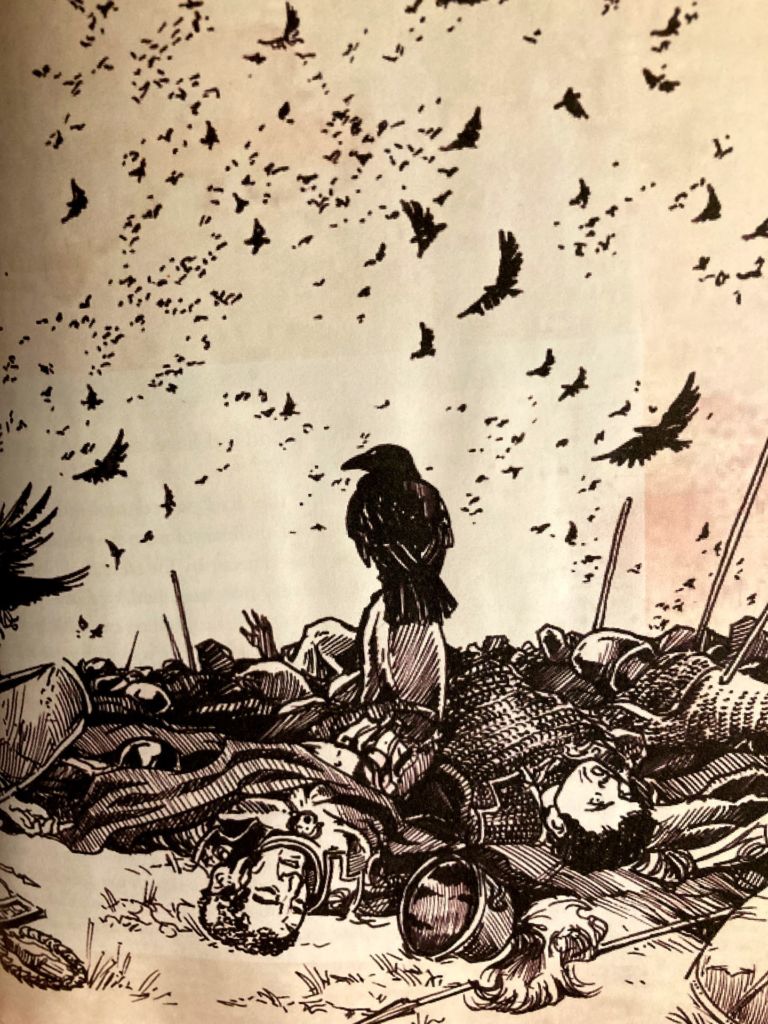

By nightfall, perhaps as many as 80,000 men in total lay dead or dying on the red-flattened fields of Cannæ. 100,000 gallons of blood spilled; over ten million pounds, tendons torn and bellies disemboweled, of rotting human flesh. Livy again provided the most affecting narration when he described the ghastly morning after. The Carthaginians, as soon as it was light,

pressed forward to collect the spoil and to gaze on a carnage that was [appalling] even to enemies. There lay those thousands upon thousands of Romans, foot and horse indiscriminately mingled, as chance had brought them together in the battle or the rout. Here and there amidst the slain there started up a gory figure whose wounds had begun to throb with the chill of dawn, and was cut down by his enemies; some were discovered lying there alive, with thighs . . . slashed, baring their necks and throats and bidding their conquerors drain the remnant of their blood. Others were found with their heads buried in holes dug in the ground. They had apparently made these pits for themselves, and heaping the dirt over their faces shut off their breath. (emphasis author’s)

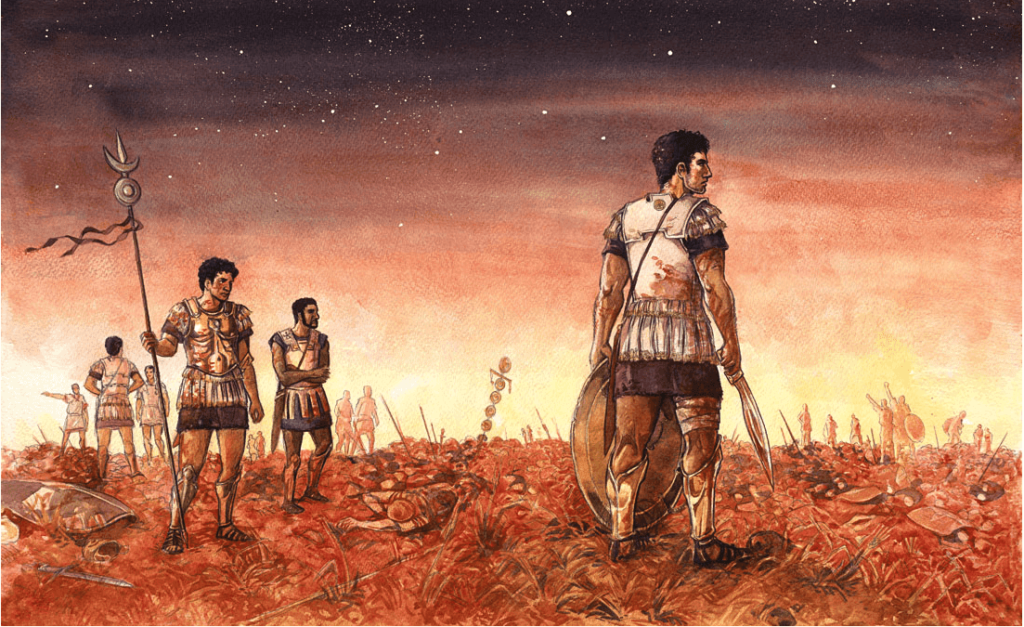

But the sight that most drew the attention of all “was a Numidian who was dragged out alive from under a dead Roman with mutilated nose and ears.” For the Roman, unable at the last to hold a weapon in his hands, “had expired in a frenzy of rage, while rending the other with [only] his teeth.”[30] [45] Hannibal, too, walked among the corpses, a ghoulish figure yanking gold rings by the bushelful from the stiffened blue fingers of dead aristocrats. The 10,000 or so Romans who had stayed behind in their base camps were quickly overrun and captured. Only a few thousand of the mightiest force to march forth from the Eternal City survived to fight another day — one of them young Scipio Africanus, whom Hannibal would face again. For Paulus, Hannibal performed a proper funeral. For the rest of the dead Romans, he left them as they lay and to the crows, wild dogs, and ravages of time and weather, whose bite was more savage even than the day’s sword had been, thus to remove the evidence of their existence and return their essence to Italy. It had been perhaps the bloodiest afternoon in human history, and the worst defeat dealt to a Western by a non-Western power. And it had come at the reasonable price of 5-8,000 dead on his own side, mainly “expendable” men collected in Gaul. Hannibal could be assured of Roman capitulation, he thought, as he washed his bloodied face in the Aufidus and thus stained its waters by his victory. At this moment, he was the master of the universe of battle. “Father,” he whispered, “here is my holy offering. Here is your revenge!”

Aftermath: The Use of Victory, the Use of Defeat

When word of the disaster reached Rome, there erupted a brief period of panic. People made their own, more frantic offerings to the gods. Women were obliged to give what they could to Queen Juno and Minerva. A statue of Mars along the Appian Way was said to have sweated blood, and roosters transformed into hens. At Capua, the sky was on fire, and the Moon fell to Earth in the midst of a rain shower.[31] [47] Small bands of survivors straggled into the city. More humiliatingly still, captive envoys sent by Hannibal to negotiate their ransom and Rome’s capitulation began to arrive and plead their case before the Senate. The Senate flatly refused. Instead, they buried full-grown sacrificial victims alive to appease Saturn at his temple; they sent the captives — aristocrats though they were, with powerful friends — back to Hannibal and whatever fate awaited them; they banned utterance of the word “peace” and forbid crying in public (Scipio the Younger would later be allowed to weep, but only after victory); to avoid widows’ public mourning spectacles, they demanded that all women remain indoors; finally, they barred the city gates to prevent a rush of refugees from fleeing the city in this, its desperate hour. More than anything else, however, was the dread of Hannibal. Surely his mercenaries would be banging on those doors soon, perhaps by the next morning.

Or, perhaps not.

Hours after the Sun had set on Hannibal’s triumph, his close friend and cavalry commandant, Maharbal, thinking that they ought not to lose a moment, boasted that “In five days’ time . . . you [Hannibal] will be feasting as victor in the Capitol. Follow me; I will go in advance with the cavalry; they will know that you are come before they know that you are coming!” But the general demurred and put him off. Astonished at his cautious attitude, Maharbal replied, “Truly it is a fact that the gods have not given all their gifts to one man. You know how to win victory, Hannibal, you do not how to use it.”[32] [48] Behold the folly of prosecuting wars without clear objectives; the unglamorous truth that attrition and logistics — not genius — will win the larger struggle. Ironically, the most complete victory of all time would forever be for nothing. It seemed that Hannibal was passionate about humiliating Rome, but not about destroying her. And so, the most audacious campaign in ancient history ended in the most anticlimactic way possible. Out of funds to pay for his mercenaries and having failed to convince enough Latin provinces to join him, Hannibal simply left and sailed back to North Africa. The man who’d been so eerily able to read his opponents’ minds on the battlefield completely misread the political will of the Roman people and completely misjudged what wars were truly made of.

Rome had no such illusions, no questions about their own war aims. They were simple, as ever: the utter destruction of Carthage. For they knew that a city rose only atop the ruins of another. “Remember Troy!” and “Carthage must be destroyed,” they cried out at regular public gatherings. It was in their blood, in the “essence” of Cannæ’s soil blackened with it.

Perhaps the great man thought his soldiers were too exhausted to continue. Maybe he wanted to savor the fruits of his audacity for a time. Or did Hannibal, surveying the carnage of victory as the Sun sank below the inky fields, meditate on all things human? Did past humiliation, present vengeance, and presentiment of future defeat overwhelm him in a sudden moment of emotion? Did he watch the Aufidus “roll with a purple flood”[33] [49] and in this foreign land name his own country? Were the hundreds of gold rings growing heavy in his purse? Burdensome, rather than triumphant? His body would have seemed leaden, but his head light as he felt the unique sensation of removing a helmet after a day of wearing it without pause.

In the half-shadows of what might have been dawn, but could have been twilight, Hannibal looked like an old, spent man. The years of hard campaigning in the saddle, of living while bound to an oath with a ghost — finally, it might have all turned from fire to ashes. When Maharbal asked his master what he meant by this reflection and wondered why he would not ride to ruin the Eternal City, the general replied that Mars, not Hannibal, has the final word. After winning the perfect battle, what else could be left but disappointment and defeat? No, he decided. Rome’s fate could wait another day.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[51]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[51]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.

Notes

[1] [52] Edmund Spenser, “The Ruines of Time,” (1591); though written as official verse and often dismissed as “uninspired,” made-to-order poetry, “Ruines” nonetheless captures all of our fears at this bastion of White Nationalism.

[2] [53] Ibid.

[3] [54] During the Bronze Age and throughout later antiquity, “the city” was the supreme expression of statehood.

[4] [55] Appian, The Foreign Wars, Horace White, ed. (New York: MacMillan, 1899), 693. Originally written ca. 150 AD.

[5] [56] Ernst Jünger, Storm of Steel (New York: Howard Fertig, 1996), 35-36; originally published in 1929.

[6] [57] By blood Scipio the Younger was a cousin of Scipio Africanus, but Africanus’ son formally adopted him as a son early in his life.

[7] [58] According to Livy, the city of Rome awarded the lady, called Busa, “public honors” for this “munificence” at the close of the war.

[8] [59] Scipio Africanus would end the Second Punic War at the Battle of Zama in 202 BC.

[9] [60] Livy, The History of Rome, Ernest Rhys, ed. (London: J. M. Dent & Sons, 1905), 321-22; originally published ca. 25 BC.

[10] [61] This shouldn’t be necessary to explain at a site like Counter-Currents, so I’ll consign this clarification to the footnotes: Carthage was a North African city in modern-day Tunisia. There have been some historically illiterate attempts to “blackface” great African civilizations like Egypt and Carthage. Though neither Hannibal nor the Carthaginians (neither the Numidians nor Libyans) were European, they were Caucasian and would have looked like today’s lighter-skinned Berber people. Hannibal probably had the tan of a commander who spent his days campaigning in the summer sun, but he was certainly not “black.”

[11] [62] See Adrian Goldsworthy, The Punic Wars (London: Cassell & Co., 2000), 147.

[12] [63] Virgil, Æneid, David Ferry, trans. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017), 128-29; originally written ca. 20 BC.

[13] [64] Livy, 285.

[14] [65] Goldsworthy, Punic Wars, 166.

[15] [66] This section of the essay takes its inspiration from John Keegan (1934-2012), a military historian who pioneered the method of closely focusing on soldiers’ personal experience of battle — the kinds of things they would have seen, felt, heard, and smelled — to gain a much richer understanding of the human face of war.

[16] [67] Adrian Goldsworthy, Cannæ: Hannibal’s Greatest Victory (New York: Basic Books, 2019), 115-16.

[17] [68] See Gregory Daly’s Cannæ: The Experience of Battle in the Second Punic War (London: Rutledge, 2002), 189.

[18] [69] One of the most affecting studies that I’ve read about this kind of physically brutal warfare is Veronica Florato, Anthea Boylston, and Christopher Knusel’s Blood Red Roses: Archaeology from the Mass Grave at the Battle of Towton, AD 1461 (Oxbow Books, 2007), a deep dive into the forensics of wounds received in medieval conflicts, injuries that would have been comparable to those suffered during the Punic Wars. There is also a wonderful (and disturbing) documentary on this mass grave that I recommend for the interested reader here [70].

[19] [71] From a first-person account of a northern soldier’s experience during the American Civil War in “Carnage At Antietam, 1862,” EyeWitness to History [72] (1997).

[20] [73] See Martin Samuels’ “The Reality of Cannæ” in Militärgeschichtliche Mitteilungen (January 1990), pp. 7-31, 15.

[21] [74] See Daly, 157 and Simon Elliott’s Romans at War (Oxford, UK: Casemate Publishers, 2020), 56-57.

[22] [75] Ancient chroniclers disagreed on the exact numbers of men who fought at Cannæ. Polybius, generally recognized as the most reliable source, claimed that 80-100,000 Romans faced around 40,000 Punic soldiers, while Livy maintained that Rome fielded perhaps 60,000 men and Carthage 30-40,000. Both attested that Carthage’s horsemen outnumbered Rome’s cavalry by a considerable margin.

[23] [76] Quoted from J. M. Dolfen’s Darkness Over Cannæ (Point Pleasant, N.J.: Winged Hussar Publishing, 2020), 59.

[24] [77] Livy, 319.

[25] [78] Ibid., 319.

[26] [79] Field Marshal Alfred von Schlieffen was a particularly enthusiastic fan of Hannibalic tactics at Cannæ.

[27] [80] See this cautionary note about violence and titillation in Robert L. O’Connell’s Ghosts of Cannæ: Hannibal and the Darkest Hour of the Roman Republic (New York: Random House, 2019), 234.

[28] [81] Polybius, Histories, Evelyn S. Shuckburgh. trans. (London: MacMillan, 1889), 367; originally written ca. 140 BC.

[29] [82] Livy, 320.

[30] [83] Ibid., 321.

[31] [84] Ibid., 324.

[32] [85] Ibid., 321.

[33] [86] An allusion to Virgil’s Æneid.