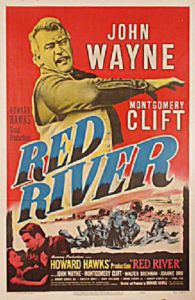

Red River

Posted By Trevor Lynch On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledHoward Hawks’ Red River (1948) is one of the greatest Westerns. Red River has it all: charismatic performances by John Wayne and Montgomery Clift, a solid ensemble cast to back them up, a beautifully economical script, dramatic black-and- white cinematography, and a surprisingly good score from Dimitri Tiomkin, who had always struck me as a hack. All of these elements are masterfully drawn together by Hawks. His sense of pacing and visual drama never fails. He grabs your attention with stark contrasts between dark and light, vast landscapes and closeups. He’ll sweep you up in action, then stop you dead in wonder.

Red River is the story of the first cattle drive on the Chisholm Trail from Texas to Abilene, Kansas. In Hawks’ hands, however, a movie about an episode in the history of America’s livestock business becomes mythic, epic, and philosophical. The frontier strips away the trappings of civilization and displays human nature and the origins of society naked in all their glory and squalor. Like such great Westerns as The Searchers [2], The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance [3], and Once Upon a Time in the West, Red River is an origin story about the transition from savage to civil society.

This transition is particularly problematic for Americans, since our default programming is liberal individualism that prizes equality, personal freedom, contractual obligation, private life, and comfort above things like adventure, conquest, honor, and glory, to say nothing of holiness and truth. Unfortunately, as Red River shows, you can’t carve civilization out of the wilderness by following liberal principles — although it is increasingly evident that liberalism can wreck any society that takes it too seriously. Liberalism forces us either to cover up the illiberal origins of our society or to destroy it in a fit of self-loathing. (But there’s another option as well: to embrace the truth about our origins and stop immolating ourselves before the Moloch of liberal norms.)

Red River begins in 1851. A wagon train is headed to California. Pioneers banded together because there is strength in numbers, and strength was needed to confront the dangers of the frontier, including merciless Indian savages. But practically the first thing we see is a wagon pulling away from the safety of the train. Thomas Dunson (John Wayne) has decided to strike south for Texas and found a cattle ranch.

The leader of the wagon train doesn’t want Dunson to go. They are all safer sticking together. Dunson understands that, but this appeal to rational self-interest falls on deaf ears. He has a vision, and he is willing to accept the risks to follow it. The leader says Dunson agreed to go to California. Dunson says he signed nothing, and as we will soon see, promises on paper mean nothing to him anyway. The leader says that Dunson is too good with a gun to lose. Dunson replies that he’s also too good with a gun to keep. In the end, it comes down to the threat of force.

Dunson has fallen in love on the trail with Fen (Colleen Gray). He wants to leave her behind as well. Founding a ranch is hard, dangerous work. She’s not strong enough. “But what about the nights?” she asks. Good question, but in Tom’s mind, starting a cattle ranch requires cows for the bulls but not women for the men. Tom promises to send for her when it is safe and gives her his mother’s bracelet (which he himself was wearing) as a token of his pledge.

This opening scene establishes that Tom Dunson is not a man to be reasoned with. Once he makes up his mind, he is immovable. Being open to persuasion, of course, is one of the principles of parliamentary democracy. Dunson, however, is quick to reach for his gun to silence his critics. He’s a budding tyrant, not a liberal democrat. But, as it turns out, it takes a tyrant to found a great ranch in the wilderness.

Dunson turns south with his sidekick Groot (Walter Brennan) plus two cows and a bull to start his herd. A few hours later, the wagon train is massacred by Indians. Dunson and Groot see the smoke in the distance and prepare to defend themselves. They kill the raiding party sent after them, but the two cows are slaughtered. Dunson also recovers his engagement bracelet from one of the braves, who surely killed Fen to take it.

The next morning, they come upon a boy named Matt Garth (Mickey Kuhn) leading a cow. He is the sole survivor of the massacre. He’s gibbering from the horror. Dunson snaps him out of it with a brutal slap. It’s a rough beginning, but Matt and his cow become the co-founders of a great ranch, the Red River D, “D” for Dunson.

When Tom finds the spot he wants to settle down on, he is greeted by two Mexican riders, who inform him that this land belongs by grant and patent from the King of all the Spains to one Don Diego, who resides 400 miles to the south. Groot thinks that’s too much land for one man. So does Tom. Groot is a Lockean, who believes that when we appropriate property from the state of nature, we should leave as much and as good for others. Tom, however, has no such notions. He wants to build his own empire. When one of Don Diego’s emissaries draws his gun, Tom kills him and tells the other to inform Don Diego of the new arrangement. When Tom releases the cow and bull, he says that wherever his herds roam will be his land. The herd will appropriate for him. (The Hungarians have a similar land-appropriation myth.) There’s no talk of leaving as much and as good for others.

Flash forward to 1865. The Red River D has become the largest ranch in Texas. Tom has killed six more men to protect it, but other ranches have started in the area.

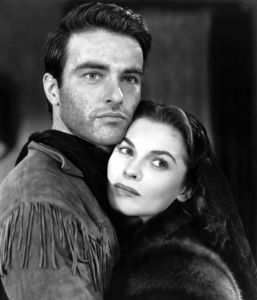

Matt has grown into a man superbly played by Montgomery Clift. Matt is the son Tom never had. But there is a strange intimacy between them. Matt now wears the engagement bracelet Tom gave to Fen. They share cigarettes with one another. When Tom starts putting his brand on other ranchers’ cattle, Matt jokes that pretty soon his will be the only rump around there without Tom’s brand. Tom says, “Bring me the iron.” There’s more than just a hint of pederasty here. This is what happens on the frontier when women are left behind as too weak.

The Civil War has ended. Matt has returned to Texas, quite practiced in the use of his gun. It goes without saying that he fought for the South. Texas is in crisis. There’s no market for beef in the defeated South, so Tom decides to drive his herd a thousand miles to a railhead in Missouri, to ship them north. They will face obstacles from men as well as nature. Indians and murderous gangs of rustlers stand in their way. It will be a brutal march, but Tom Dunson is a man of enormous will. He will make it happen.

As the drive progresses and obstacles mount up, Tom wears out cattle, horses, and men. The men become sullen and restive, and Tom becomes increasingly obsessive and tyrannical: Captain Ahab in a saddle.

Tom has no sense of being on equal footing with other men. He doesn’t listen to them. When the men learn that they can drive the herd to Abilene, Kansas and avoid the Missouri border gangs, Tom will hear none of it. His mind is made up.

Although the story began with Tom quitting the wagon train, when three men propose to quit the drive, Tom guns them down. When three more desert, Tom sends a gunslinger to retrieve them. One is killed and two return. Tom then says he is going the hang the deserters.

But this time, he has gone too far, and Matt leads a mutiny. They will take Tom’s herd to Abilene and leave Tom behind. Tom vows to kill Matt, and Matt believes him.

[4]

[4]You can buy Trevor Lynch’s White Nationalist Guide to the Movies here [5]

Tyranny might have been necessary to create the ranch and start the drive. But men are not animals, and Matt’s more democratic style of leadership is necessary to finish it. As the men move closer to civilization, they begin taking on some of its features. And in this case, who can blame them?

In the last act of Red River, Matt completes the drive. When his scouts find a wagon train ahead, complete with women and coffee, Matt changes the drive’s course to meet them. The men clearly need a break, and they are low on supplies. Tom never would have considered it. When the wagon train comes under Indian attack, Matt abandons the herd and rides to the rescue. Tom never would have bothered.

But in many ways, Matt is like Tom. When Matt meets a beautiful woman, Tess Millay (Joanne Dru), in the wagon train, it is clearly love at first sight. She wants to leave with him, but he refuses. She’s too weak for the road ahead. She’s been wounded by an Indian arrow, but beyond that, she’s a woman. Matt leaves her with Tom’s engagement token.

Meanwhile, Tom has gathered some gunmen and set off in pursuit of Matt. He knows he is getting old. He knows that Matt is the closest thing he will ever have to a son. He knows that if he kills him, there will be nobody to carry on his vision once he has gone. But his wrath is too great. He is like Wotan in Wagner’s Siegfried, who knows that his grandson Siegfried is his only hope for the future but still warns the lad not to tempt his wrath, lest it bring both of them to ruin.

Tom’s wrath is his thumotic side expressing itself. Up to this point, Tom has shown immense willpower, but it is all in service of building a ranch. He’s a titan of industry, but at bottom he’s just a merchant. Now we see Tom willing to throw away everything he has built to avenge a very personal betrayal. It is one of John Wayne’s greatest performances. When Tom finally catches up to Matt, he is genuinely terrifying, striding straight through the milling herd toward Matt, murder in his eyes.

It is an amazing buildup to one of cinema’s most anticlimactic and farcical resolutions. The mythic and heroic thrust of Red River points toward a bloody end: the unstoppable force of Tom Dunson versus the unmovable object of Matt Garth. Tom’s wrath is too great to be turned aside by words. One of them has to die. The only really happy ending possible is Matt killing Tom. It is terrible to have to kill one’s tyrant father, but it is the only way to secure a future. It would be a powerful coming-of-age story.

Instead, however, Matt allows Tom to shoot at him. Is he used to this kind of abuse? Is Matt acting the role of Jesus, letting his father expend his wrath on him? But Matt can’t stop bullets or rise from the dead, so it seems like madness. Normally, it would mean Matt’s death. So our storyteller — with flawless anti-tragic instincts — contrived to have Tom wounded by one of Matt’s friends, so his aim is off. Then Tom begins beating Matt until Matt fights back. At this point, both are so tired that it is clear that nobody will die today. The duel to the death over honor has been replaced by a scuffle in the dirt.

Having averted tragedy, the movie then plunges headlong into farce. Tess Millay breaks up the fight by firing off a gun. Tom and Matt are breathless, bloody, and sprawled on their asses amid a peddler’s pots and pans. But they seem most stunned by the fact that they are being scolded like naughty children by a woman waving a gun around. Tess’s ravings are a classic case of dismissing the masculine struggle for honor — which basically encompasses the whole field of human history — as just a childish game. There’s no question that Tom’s resolution to kill Matt is unhinged, but it isn’t silly. Neither is most of human history. But, to borrow a line from Camille Paglia, if Tess Millay had her way, we’d still be living in grass huts.

When Tom met Tess while pursuing Matt, he offered her half his fortune to bear him a real son who could replace Matt. There’s a lot going on here: Matt cuckolding Tom by taking up with a woman, Tom cuckolding Matt to father an heir to displace him, Tess saying she’ll take the offer if Tom calls off his vendetta, which reveals that Tess will only marry Tom because she’s in love with Matt, and who knows how many layers of love, jealousy, and spite. But now Tom suggests that Matt should marry Tess after all.

This reminds me of another Wagner story. In Die Meistersinger, Hans Sachs renounces the much younger Eva so she can marry Walter, a knight closer to her age. One of the core themes of both stories is what Erik Erikson called “generativity”: older generations promoting the well-being of younger generations to ensure the survival of the species.

At the heart of generativity is renunciation. Life has to go on, and if the old do not relinquish power to the young, then none of us have a future. But still, I find Tom’s sudden transformation from embittered, power-mad killer to great big softie too quick. Nothing we have seen in the movie so far makes this change plausible.

Red River is an entertaining and emotionally powerful epic about the conquest of a continent. But in the last few minutes, it whisks us straight from barbarism to decadence: from frontier patriarchy to schoolmarm matriarchy. You can criticize it as drama, but you can’t fault it as a history of America.

The Unz Review, November 24, 2021 [7]

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[8]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[8]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.