“For the Dead, They Travel Fast”: Sightings of the Phantom Horseman

Posted By Kathryn S. On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledThe year was 939 AD, the setting near the city of Simancas. Count Fernán Gonzalez, a commander of free Spain, rode at the head of an army whose mission was to strike a blow against the Saracen invaders of Al-Andalus. Still, they were outnumbered and desperate. Fortune, it seemed, would favor the Moors on this day. But as the Count’s troops prepared to clash with their foe, a miracle occurred. While the “good people were in this doubt” of strength, they turned their gazes heavenward, where they saw a figure fair and shining. Indeed, he was much “whiter than the recent snows”; his “face was angelic, [his] form celestial.” Astride a horse, also “whiter than crystal,” he came down “through the air in great haste” and alighted on the plain. Then, he “looked at the Moors with fierce glance, the sword in his hand [was] frightful to see.”

It was the spirit-warrior of Santiago the Great, come at his people’s hour of need; come “singing in the sun, sword unsheathing” to slay the infidel. Spanish hearts were now fired “out of doubt, out of dark” by this phantom horseman and the white standard that billowed behind him as he rode.[1] [2] They charged. The joy of battle had possessed them, and the Spaniards met their enemy with a laughing fury. Thanks to the aid of their saint, they routed the Moors and achieved a complete triumph. Santiago vanished into his victory. But it was not the last time that he would appear on a Spanish battlefield. Santiago’s recurring presence was a striking example of the “phantom horseman” genre, a phenomenon prevalent in European/nationalist folklore. Has there been any more iconic image than a man on his horse?

Until very recent history, harnessing horsepower was the fastest way to travel by land, a fact that was unchanged for thousands of years. The horse was therefore crucial — and crucially, it was a beautiful animal, especially when seen in stride. Thus, the image of the horseman has always been a particularly rich symbol for European peoples, and story-weavers have used him to great effect. He was often a man of the frontier, whether that meant herding cattle through the Dakota badlands; wandering the frozen wastes of Muscovy; or galloping across the steppes of ancient Dacia. The horseman could be a rugged “lone ranger,” or a member of a communal, highly-disciplined order of dragoons. He took the form of an aristocratic cavalier, sporting both a polished hussar uniform and a handsome mustache. He was the messenger, carrying quotidian pieces of mail, but also rumors of war — “The British are coming!” and “Cannae is lost!” The rider was sometimes the wild nomad who scorned settled life in favor of the saddle; but he could be too the patient hunter with families awaiting his return. Exalted both literally and figuratively, the horseman was the highest position to which mortal men could aspire: something less than god-hood, but it was certainly a pedestal that often signified dash, wealth, and mastery. Countless hours were needed to perfect the art of jumping and wheeling, of merging with one’s horse. A man’s legs had to become more steel than muscle in order to remain aloft during moments of flight or panic. Mistakes resulted in calamity. Breaking one’s neck was not an uncommon fate for even the most experienced riders.

Given his profound significance as both reality and symbol, it should not surprise us that he has appeared often in our supernatural and spiritual traditions as the ultimate ghost. In this role, the Phantom Horseman has had different, but complementary functions. He could be, like Santiago, a bringer of Victory/Justice. His other forms were as sender of thunder, a seeker of lost things, or finally, a messenger of prophecy. The existence of such beings, such age-old customs across the time and space of Western history, were made possible by virtue of a belief in which the dividing line between the human and divine, natural and supernatural, was abolished. Erased. Paganism and Christianity infiltrated each other. Ghosts in general, and phantom horsemen in particular, required dark and bloody ground from which to rise from the grave. Tales like these needed a people rooted to the soil and souls of their ancestors, from whom they inherited a haunted past. The Phantom Horseman was the vessel-symbol of Western dreamscapes; the primordial icon of fear and awe. Just as most white spirituality revolved around the cycle of sowing, tending, reaping, and weathering through, so did spirit horsemen arrive at an appointed season, and nightfall and high noon were their hours. Do not think to escape them, readers, nor of trying to outrun their mad dash, for mortal men can only drag their feet of clay, and “the Dead, they travel fast.”[2] [3]

I. Bringer of Storm/Thunder: The Wild Hunter

During the bleak winter months, the northmen endured the wind-storms caused by Odin and his hunting parties. Huddling together indoors, old and young gathered around the Yule fire. It was once customary to tell ghost stories, not on All Hallow’s Eve but during the Christmas season. When the winter “winds [blew]” and all came in from the cold, from “the dark paths” and “wild heaths,” imagination took flight. Those unwise enough to wander by themselves during these frostbitten nights risked something worse than exposure. They may have heard a “sudden rustling through the tops of the trees — a rustling that might have been the wind, though the rest of the wood [lay] still.” Then, descending upon them with “the barking of dogs,” the host of “wild souls,” would sweep down in a waterfall of sound.[3] [4] Odin sat astride his eight-legged horse Sleipnir, a creature who brought thunder in the wake of his hooves. Fire flashed in the eyes of god and stallion alike. Whips cracked like lightning, and a swirl of shadowy shapes obscured the stars. For their part, mortals prayed that nothing would breach the rattling windows from outside. For what purpose they’d come, not even the elders could say.

Percy Shelley’s nineteenth-century poem “The Spectral Horseman” expanded on the sublime character of the Storm-bringer. Neither did this rider have definite aims, but he shrieked across the sky, “winged with the power of some ruthless king,” and come to sate his fury on “the ruins of time that were past.” His chariot flew “o’er breast of the prostrate plain.” A raving meteor at midnight. In a low voice, a cold voice, a hollow voice, he thundered — a rumble “not heard by the ear, but felt in the soul.” As the “phantom courser scoured the wintry waste,” peasants saw the “blue flash” of his form fly by and shuddered. Before dawn and the end of his revels, the rider shook “from his skeleton folds [all manner of] nightmares” and summoned the “tombless ghosts” of the dead. Thus joining the “Spectral Horseman” on his vaunt, these freed, yet enthralled spirits groaned their “unearthly sounds,” mingling them with the stampeding boom and swelling shrills of music lifted up into “the moonlight air.”[4] [5] An orchestra of ice and terror.

[6]

[6]You can buy Collin Cleary’s Summoning the Gods here [7].

Storm-bringers like Odin and Shelley’s “ruthless king” were both supernatural forces and forces of nature. At one with horse, cloud, and sky, they gathered the dead from their rest and spooked the living. Still, they lacked particular targets for their wrath. Only the spell of winter could explain these dreadful horsemen who froze all the forests and fields with their breath. This was the “Wild Hunt,” a motif widespread in Scandinavian and Germanic cultures. It was best expressed as the terrifying concourse of “lost souls riding through the air [and] led by a demonic leader on his great horse, which could be heard passing in the storm.”[5] [8] The medieval “Wild Hunt” may have been a remnant of an ancient Norse feast of the dead, a commemoration rite celebrated when all those who had died the previous year came down during the Epiphany as a wild rush of spirits.

J. R. R. Tolkien, lover of northern myth, captured this “wild ride” of the dead when he wrote of his “Shadow Host” at Dunharrow: an army cursed with “living death” as punishment for an old betrayal. As Tolkien’s heroes made their way through the “grey wastes” in order to summon these ghosts to battle, they saw “shapes of Men and of horses, and pale banners like shreds of cloud, and spears like winter-thickets on a misty night.”[6] [9] The Dead followed behind. Suddenly, the Shadow Host that had hung back “rose as hunters at the last.” They “came up like a grey tide, sweeping all away before it.” Observers heard sonorous murmuring, as if it were “an echo of some forgotten battle in the Dark Years long ago”; faint cries, dim horns, and the mutters “of countless voices.” The riders drew their “Pale swords” — but they “no longer needed any weapon save fear.”[7] [10] None would withstand them.

II. Bringer of Prophecy: The Messenger of Doom

The most well-known example of prophetic horsemen bringing what Tolkien would call “fell tidings” comes to us from the Book of Revelations — a series of apocalyptic prophecies. When the End Times arrive, all “the kings of the earth . . . will say, Alas . . . that great city Babylon, that mighty city! for in one hour is thy judgment come.” From the shadows there will supposedly emerge Four Horsemen: behold the first, “a white horse: and he that sat on him . . . a crown of laurel was given unto him: and he went forth conquering, and to conquer.” The Antichrist. Then, the second beast will arise and say, “Come and see another horse, red . . . and power was given to him that sat thereon to take peace from the earth . . . [and] there was given unto him a great sword.” The wages of war.

Next emerged a rider on “a black horse; and he that sat on him had a pair of balances in his hand.” The final judgment. And last, the spookiest horseman followed his fellows. Behold “a pale horse: and his name that sat on him was Death, and Hell followed with him.”[8] [11] The devil’s pestilence. Unlike the indiscriminate Bringers of Storm, these four figures had instructions: to level the sinful world. The prophetic Messenger is the thundering Huntsman’s complement. Like those of thunder, the Messenger trails ruin behind him, but the latter has specific purposes and particular targets in mind. While a wild storm-hunt is a force of nature, the force behind the Messenger is Fate, or the gods’ will.

While it’s common to receive a cheerful palm, tea-leaf, or astrology-pop reading, no one ever receives a heartwarming prophecy. Even though we realize that mirrors and seeing-stones are perilous guides, we still want to peer into the glass. Having gazed at the Palantír, one of seven “seeing-stones” mentioned in the Tolkien universe, Pippin the Hobbit revealed the images that the orb had shown him: fires consumed a withered, white tree, and monsters like bats “wheeled round” a tower; the screams of men in extremis howled in his ears. The vision forced the wizard Gandalf to take Pippin and ride east for Gondor’s capital, bringing this warning to its people. For the task, the wizard whistled for Shadowfax. Together, all in white, the horse and master, they raced forward like a vision from the First Age, and “fire flew from” Shadowfax’s hooves. Just before sleep claimed him, lulled by the gentle landing of magic footfall, Pippin had a strange feeling: “that he and Gandalf were still as stone, seated upon the statue of a running horse, while the world rolled away beneath his feet with a great noise of wind.”[9] [13]

There are further examples of marble horsemen, prophecy, and sleep-induced visions. Ambrose Bierce’s short story of the Civil War, “A Horseman in the Sky,” is especially compelling. It began at dusk. A young Northern picket named Carter Druse lay concealed by the road’s angle and near a large clump of laurel — the laurel that in ancient Greece crowned Apollo at Delphi’s Oracle; that in Rome and Revelations crowned the victors after conquest; and in the nineteenth century, the wreath that crowned the headstones of the dead. Druse fought sleep. Though he was a native Virginian, he had announced to his father two years before that he intended to enlist on the side of the Union. His father was unimpressed. The patriarch had lifted his leonine head, looked at his son a moment in silence, and replied, ‘Well, go, sir, and whatever may occur do what you conceive to be your duty. Virginia, to which you are a traitor, must get on without you.”[10] [14]

Now the son was on the lookout with strict instructions to stay alert and shoot any Confederates should he see one. If caught asleep, the punishment for him was death. But eventually, he lost the battle with exhaustion, and succumbed. Upon awakening, he saw before him a proud and straight-backed horseman, bathed in moonlight and overlooking a cliff. A Confederate. The stranger stared at the Union army below as if noting numbers and positions. Druse instinctively closed “his right hand about the stock of his rifle,” but his “first feeling was a keen artistic delight.” The Confederate horseman was silhouetted to perfection. There, as if on a “colossal pedestal . . . motionless at the extreme edge of the capping rock and sharply outlined against the sky, — was an equestrian statue of impressive dignity.” This arresting figure sat “with the repose of a Grecian god carved in marble.” Should Druse offer him laurel, or lead? For an instant, he had a strange feeling that he had “slept all through the rest of the war and was looking upon a noble work of art reared upon that eminence to commemorate the deeds of an heroic past.”[11] [15] Mirroring Pippin’s sleepy descent into a dreamworld of stone figures carved from the bones of the earth, so did Druse watch solemn monuments pass through the compressed time of prophecy. The Confederate horseman foretold the future. Soon, only monuments would remain of his proud people. Then, the stranger turned his head. The young picket grew pale and dizzy, “shaking through every limb.”[12] [16] But duty prevailed.

He aimed. He took the shot.

A Union officer below then “saw an astonishing sight.” For a sublime moment, a man on horseback rode “down into the valley through the air.” In impeccable military fashion, he fell still seated in the saddle. His bare head and “his long hair [were] streamed upward, waving like a plume,” or a lion’s mane. The mare’s “body was as level” as if every hoofstroke encountered the resistant earth, and its motions were those of a wild gallop. Terrified, the Yankee officer half believed that this ghost was ushering in “some new Apocalypse.”[13] [17] Until a crash sounded in the trees and died without an echo.

Some time later, Druse’s commander demanded to know if the young man had seen anything. “Whom did you shoot?” he asked. Still pale, the picket answered, “My father.” It seemed that when the older man had charged his son to “do his duty” without shirking his task for any reason, he’d spoken the prophecy of his death and the doom of Virginia. Druse had already failed in his oath by falling asleep on the watch. Napping was forgivable. Sparing his father, it seemed, was not. The larger meaning of Bierce’s story was the War’s severing of blood ties between North and South, father and son. The nation has not recovered from this awful ride, which, as Bierce suggested, was more of a death-dive.

III. Seeker of Lost Things: The Midnight Raider

[18]

[18]You can buy Kerry Bolton’s More Artists of the Right here. [19]

Indeed, all wars are fruitful of corpses and ghost stories. According to Tolkien mythology, an evil god-king once tricked the people of Middle-Earth into forging and wearing rings of power: three for the elves (“eldest of all”), seven for the dwarves (“delvers . . . of dark houses”), and nine for mortal men (“masters of horses”). Unfortunately for this gullible group, the Dark Lord forged his own ring that ruled all the others and gave him the power to conquer Middle-Earth. The nine mortal kings were unable to resist his corruption. They became his lieutenants and the most feared beings in the world. To most, they were known as “Ringwraiths,” or the Nine Nazgûl. In the Second Age, an army of elves and men won an improbable victory over the forces of darkness. The royal heir of Gondor cut the Dark Lord’s ring from his hand, and the sorcerer’s spirit seemed to vanish into the void. But instead of destroying the ring, the prince chose to keep it. Over vast stretches of time, the ring changed several hands, until it finally came to a hobbit, one who inherited the gold band from an uncle.

Although people had long since forgotten the legend of the “Lord of the Rings” by the end of the Third Age, some had detected a shadow rising in the east. Evil news and rumors grew increasingly worrisome. The Dark Lord had returned, and he only needed the ring to permanently enslave all the races in Middle-Earth. To that end, he dispatched his Ringwraiths, commanding them to find the ring and to kill whoever carried it. The Nine rode out from the haunted city of Minas Morgul and crossed the Isen River on Midsummer’s Eve, intent on their mission of finding the lost Ring of Power. When the hobbits first glimpsed these demented shadow riders, they thought that “they seemed to sit upon their great steeds like threatening statues upon a hill, dark and solid, while all the woods and land about them receded as if into a mist.”[14] [20] In the manner of an amazed Union picket, they shared a moment of dizzy wonder at effigies that seemed cast in blackest rock. Beneath their cloaks, the riders had no tangible form, and their hoods framed a headless void. Their true features could only be seen in the “shadow realm.”

The terrified bobbits watched as the Nine threw off their cowls and revealed themselves. Underneath the disguise, the wraiths’ robes were “white and grey.” Gleaming ribbons of shade-light twisted around their crowns and their cruel mouths and their “merciless eyes.” Their swords smoldered in pale-naked hands; to one another they spoke with “drawn-out wails, like the cry of some evil and lonely creature.”[15] [21] Any humanity or independent will these cursed kings may have once possessed had so long ago been extinguished, that they had forgotten their own names. Their one obsession, their single thought, was bent on recovering their master’s Ring of Power.

The Ringwraiths’ shadowy appearance and ability to paralyze onlookers with terror has, like the “Wild Hunt,” much older precedents. Gothic novels of the eighteenth century inspired a kind of delighted horror within their readers, and one of the most popular motifs of this genre was the “banditti gang.”[16] [23] These were highwaymen operating along the interstitial edges of civilization and the wilderness. Because of their appearance and skilled horsemanship, they acted with sadistic impunity. They too sought the spoils of midnight raids, and wanted like the Nazgûl, to rob and murder their victims. Peter Teuthold’s The Necromancer (1797) described “the banditti” as black-clad and “ghostly horse riders from an abandoned castle.” They communicated in frightening and esoteric signs understood only by themselves. A group of investigators, an army lieutenant and a baron, received an eerie reception at these riders’ castle:

Every thing was silent. But in an instant the former noise struck our ears once more, and the infernal hosts rushed by like lightning — [we] darted to the passage leading to the gate, but the airy gentlemen were already out of sight, and we could see nothing save a faint glimmering of horses . . .[17] [24]

And just as the gatekeeper at Tolkien’s town of Bree once warned the hobbits of “queer folk about” during the witching hours, so did Teuthold’s innkeeper caution against wandering after sunset, lest travelers be ambushed by those “infernal spirits.” Indeed, the banditti kept the village in a state of “pacified terror”: residents had become “used to that nocturnal sport” enjoyed by the murderous thieves.[18] [25]

Which brings me to the most famous phantom horseman of the bunch — the product of another Gothically-inclined author of the same period. The stomping ground of this next Seeker was Sleepy Hollow, an old Dutch community nestled in the hills along the Hudson. A drowsy little place where “dreams [waved] before the half-shut eye.”[19] [26] Like the Ringwraiths, Washington Irving’s Sleepy Hollow ghost had been defeated during battle. Some speculated that he was one of those hated Hessians, mercenaries whom the British had shipped across the Atlantic in order to help put down the Revolution some years before (due to the story’s fame, this Hessian has ironically become very American). Indeed, Sleepy Hollow was a community where the scars of the Revolution had not healed. The ill-fated British officer John Andre, killed for the crimes of Benedict Arnold, was said to haunt a gnarled tree near the old churchyard. Hessian and British spy — two outsiders who’d each met their doom at the hands of American rebels. The place, Irving’s narrator described, was rich in “legendary treasures of the kind. Local tales and superstitions thrive best in these sheltered long-settled retreats,” he mused, “but are trampled under foot by the shifting throng that forms the population of most of our country places.” No surprise, then, that we seldom hear of ghosts, “except in our long-established Dutch communities.”[20] [27] Ghosts, in other words, needed places with history. Not only will the preservation of Americans and Europeans within their native lands save our race, but it will save our ghosts as well.

It was into this small Dutch town that gangly Ichabod Crane came riding. He had accepted the job of local schoolmaster. And despite his odd looks, Ichabod was able to charm most anyone. But the only woman he cared to woo was Katrina Van Tassel, the daughter of a wealthy farmer. This put him into conflict with local tough Brom Bones, also a suitor for Katrina’s affections. One night, and during Mr. Van Tassel’s annual harvest party, Brom told the story of the Headless Horseman, hoping that Ichabod would be so alarmed by the ghoulish legend that he’d leave Sleepy Hollow and never return. The demon-ghost, Brom claimed, appeared on All Hallow’s Eve, searching for a head with which to replace the one he’d lost in battle. And he wasn’t picky.

After listening to this yarn, the spooked Ichabod hastened to the stables and mounted his old horse Gunpowder. But it had already grown dark and the land was plunged into a profound shadow. The blood drained from his face, and Ichabod looked fearfully from side-to-side for long minutes. When the specter failed to show, he breathed a slow sigh of relief. Of course, he scoffed. The story had been another of Brom’s pranks. This was premature. In that instant, the schoolteacher saw a black shade emerge from the trees. It appeared to be “a [man] of large dimensions and mounted on a black charger of powerful frame.” Worse, there was nothing above his broad shoulders. The Headless Horseman! A frantic chase ensued. Ichabod spurred Gunpowder toward the bridge that Brom had claimed the Horseman would not cross. Most ghosts, after all, had limits. But as he and his mount rode over the creek, so too did the “goblin rise in his stirrups,” and he hurled a flaming pumpkin at Ichabod’s head. The schoolmaster tried to dodge the horrible missile. But too late. It “encountered his cranium with a tremendous crash — he was tumbled headlong into the dust, and Gunpowder, the black steed, and the goblin rider, passed by like a whirlwind.”[21] [28] The next day townsfolk found “deep horse tracks” that evidenced a scene of “furious speed.” Ichabod’s hat floated below in the creek, but there was no sign of its owner. Most assumed that he’d simply decided to leave. Others weren’t so sure. The “old country wives . . . who are the best judges of these matters, maintain[ed] . . . that Ichabod was spirited away by supernatural means.”[22] [29] The mystery of his fate became “a favorite story often told about the neighborhood ‘round the winter evening fire.” Brom, meanwhile, took the thing he’d always sought: the head of Van Tassel’s fortune.

IV. Seeker of Justice/Victory: The Knight-Errant

The phantom Knight-Errant was often as mysterious and magical as the demon highwayman. But this ghost did not steal, nor did he harm the innocent. The Knight-Errant’s purpose was to restore justice, or to confront evil — the foil of the Midnight Raider. Instead of diminishing his people through terror, he became a symbol of white and Western unity. Spanish Santiago, Frankish Roland with Charlemagne (later Saint Joan), and English King Arthur were national avatars that issued from a single, spiritual source. The image of a mounted, brash (but still unfailingly courteous) knight of enigmatic origins thrilled the medieval imagination. He observed fairness and a chivalric code of conduct. He kissed the lady’s hand even as he challenged her lord to a duel of honor. Tournaments and competitions encouraged masculine aggression, while they channeled such energy into scripted plotlines: testing a man’s goodness of heart, as well as his prowess in combat. It was violence with limited destruction involved. At least, this was the idea.

The fourteenth-century Arthurian romance Sir Gawain and the Green Knight was one of the most well-known literary examples of this kind of chivalric-play that involved the Phantom Horseman. It was King Arthur’s custom, “wherever his court was holden,” not to eat upon “festival so fair, ere he first were apprised of some stirring adventure . . . or a challenger should come a champion seeking to join with him in jousting, in jeopardy to set his life against life.”[23] [31] At the start of one Yule feast, the king and his knights got more than even they had bargained for. As the wine goblets were passed and toasts raised to the king and his queen, the castle doors blew open. All laughter died in their throats. There strode through the portals of Camelot’s hall

a perilous horseman, the mightiest on middle-earth in measure of height . . . his limbs so long and so huge, that half a troll upon earth I trow that he was . . . at the hue men gaped aghast in his face and form that showed; as a fay-man fell he passed, and green all over glowed . . . even the horse that upheld him in hue was the same . . . a green horse great and thick . . . he matched his master well.[24] [32]

[33]

[33]You can buy James O’Meara’s book The Eldritch Evola here. [34]

What magic was this? Was it the glitter of jewels — emerald, sapphire, and jade — that shone from his raiment? Was it the color of nature, of growing things that made him thus glimmer? Or did he glow from the green fires of a supernatural spell? Whatever it was, the Green Knight awed all who watched his approach. Then, he bellowed forth a challenge to the men assembled at the Christmas supper: “If any fellow be so fierce as my faith to test,” hither let him “haste to me and lay hold of this [axe] – I hand it over for ever, he can have it as his own – and I will stand a stroke from him, stock-still on this floor.” But only, the knight went on, “provided thou’lt lay down this law: that I may deliver him another.” A beheading-game! It was then that Sir Gawain, seated at the queen’s side, stood up and begged his liege to allow him to confront the visitor. As “the weakest . . . and in wit feeblest,” it would be the “least loss, if I live not,” Gawain explained. Only because “you are my uncle is honor given me: save your blood in my body, I boast of no virtue.”[25] [35] A man who acknowledged the importance of blood and his humility next to the greatness of his forebears — a refreshing attitude, readers.

Gawain seized the axe, then did as the green horseman had challenged. As if through nothing but air, Gawain’s blow sliced the Knight’s head from his shoulders. Blood “burst from the body, bright on the greenness.” Yet the Knight did not falter, but “stoutly he strode forth and . . . caught up his comely head and quickly upraised it.”[26] [36] Hastening to his charger, he laid hold of the bridle and swung himself into the stirrup-iron, all the while holding his skull by the hair. Remember our deal, Gawain, the mouth on his gruesome head admonished. By this time next year, meet me at the Green Chapel, so that you may receive an answering blow! As quickly as he’d arrived, the horseman hurtled from the castle and into the cold night beyond.

The seasons slipped by swiftly. After Christmas there came the “crabbéd Lenten . . . there open[ed] . . . blossoms [that] burgeon[ed] and [blew] in their hedgerows.” Clouds flushed around the summer sky; the Zephyr went “sighing through seeds and herbs.” Then, the Harvest hurried in, and “all grey [was] the grass that green was before.” Thus the year ran away “in yesterdays many, and here winter [wound] again, as by the way of the world it ought.”[27] [37] Heavy with his honor-debt, Gawain left Camelot and rode toward the Green Chapel and certain death. Breaking the law of his oath never occurred to him.

Finally, he came upon a castle, and the lord and lady there revealed to him that the Green Chapel was nearby. As the date of his rendezvous was days away yet, Gawain accepted their hospitality and stayed with them for three nights. By day, his host went hunting while Gawain remained at the manor, where the lord’s beautiful wife entertained him. At the end of each day, per the host’s instructions, they each exchanged their spoils. And each day the lady attempted to seduce her guest with kisses. Gawain politely rebuffed her efforts and repaid her lord the kisses he’d received without confessing the culprit of these advances. But on the last day, the lady gifted Gawain with a magic green girdle. It would protect him, she claimed, from any blow dealt. At last tempted, he took the sash and did not give it to his host when the man came home from the hunt. Instead, Gawain tied it to his waist the next morning — a talisman against the Green Knight’s axe. For this dishonesty, the Green Knight gave him three blows — two feints and one a slight cut on his neck. His magical disguise fell away, and the Green Knight then revealed himself to Gawain as the hunter-lord. You were true against all temptation, the lord said, until you kept secret the green sash; for this, I have bloodied you with a graze. Justice had been served.

Ashamed of himself, Gawain begged for his pardon. But the other man simply laughed: “I hold it healed beyond doubt, the harm that I had. Thou hast confessed thee so clean and acknowledged thine errors, and hast the penance plain to see from the point of my blade, that I hold thee” delivered of sin.[28] [38] Gawain departed, resolving to wear the green belt as a warning against dishonor and dishonesty, of cheating the law of his sworn word. The Green Knight had not been a specter of darkness, after all, but a warrior upholding the chivalric code of Goodness and Right.

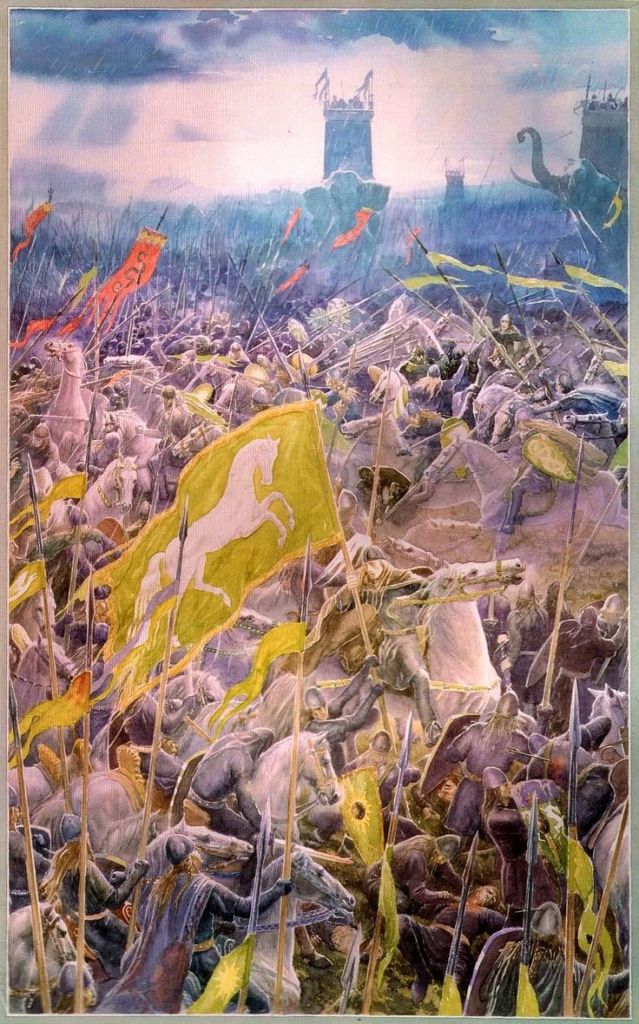

I have used Tolkien’s translation of The Green Knight, because his world of Middle-Earth is a common thread that ties all these phantom horseman myths together. It was clear that Tolkien loved him, especially the Seeker of Victory. Western man’s finest hour on Middle-Earth dawned the morning of the Battle of Pelennor Fields. King Théoden led Rohan’s riders to Minas Tirith. For a moment, as the King looked across at the besieged city’s agony, surrounded by masses of dark and foreign foes, he seemed to “shrink” into himself. They were too late! Too late was worse than never! “Perhaps Théoden would quail, bow his old head, turn, slink away to hide in the hills.”[29] [39] Fortune, it seemed, would favor the enemy on this day. But then a miracle occurred. Théoden straightened in the saddle as if possessed by an ancient warrior. He turned a fierce glance on the Easterlings with their scimitars and Haradrim with their exotic elephants. “Death! Ride to ruin and the world’s ending!” The King cried to Snowmane, “and the horse sprang away. Behind him his banner blew in the wind, white horse upon a field of green . . . After him thundered the knights of his house,” but none could outpace Théoden on the charge. “Fey he seemed,” a phantom of his fathers’ battle-fury and “borne up on Snowmane like a god of old.”[30] [40]

By sunset, victory was his, though he and most of his company lay dead on the field. Long now they have slept “under [the] grass . . . by the Great River. Grey now as tears, gleaming silver, red then it rolled, roaring water: foam dyed with blood flamed at sunset.” Above them the “mountains burned” as beacons in their high palaces. But the King’s spirit fled from his body untroubled and higher even than they. Swiftly he rode, bound for the halls of his fathers, in whose “mighty company” he was “not now ashamed,” for Théoden, Horse Master, had “felled the black serpent.”[31] [42]

Apart from inspiring audiences with songs of warriors-kings, or thrilling them with dark fantasies of saracens, raiders, and rings, the Phantom Horseman was a myth that bound white communities together. It is the chief value of legend, Tolkien would have agreed, “to mix up the centuries while preserving the sentiment; to see all ages in a sort of splendid foreshortening.”[32] [43] Tradition was the telescope of history, and the tradition of the Phantom Horseman became part of many proud “memories.” He drew the community ‘round the fire to dispel winter for an evening; drew the young to listen to shivery tales from the agéd, and to learn their elders’ lessons. This, readers, was the true gift of the ghost story.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

[44]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

[44]If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.

Notes

[1] [45] Américo Castro, The Structure of Spanish History, Edmund L. King, trans. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1954), 136. Santiago was the Spanish name for Saint James, the Apostle. The territory of modern-day Spain was James’ to convert, though it’s unclear whether or not he ever set foot in those lands before being martyred in Jerusalem. According to tradition, his remains lie at the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela in Galicia, Spain. The spirit of Santiago was, Castro argued, a syncretic figure whose origins had multiple sources. He became the rallying saint for the “counter-jihad” during the Reconquista.

[2] [46] Muttered by a fearful traveler in Bram Stoker’s Dracula, as the carriage arrived to take Jonathan Harker to his destination high in the Carpathian mountains. The speaker referred to the eighteenth-century Romantic poem “Lenore [47]” by Gottfried August Burger.

[3] [48] Kveldulf Hagen Gundarsson, “Mountain Thunder,” in Sigurd Towrie’s “The Wild Hunt [49]” (2021).

[4] [50] Percy Bysshe Shelley, “The Spectral Horseman [51].”

[5] [52] See Michael Burgess’ “Oromë and the Wild Hust: The Development of a Myth,” in Mallorn: Journal of the Tolkien Society (1985) pp. 5-11, 5.

[6] [53] J. R. R. Tolkien, The Return of the King [54], 28.

[7] [55] Ibid., 82.

[8] [56] See Rev. 6, KJV.

[9] [57] J. R. R. Tolkien, The Two Towers [58], 121.

[10] [59] Ambrose Bierce, “A Horseman in the Sky” from Tales of Soldiers and Civilians (San Francisco: E.L.G. Steele, 1891), 62.

[11] [60] Ibid., 62-63.

[12] [61] Ibid., 63.

[13] [62] Ibid., 64.

[14] [63] J. R. R. Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring [58], 102.

[15] [64] Ibid., 121.

[16] [65] See Joel Terranova’s “Eighteenth-Century Gothic Fiction and the Terrors of Middle-Earth,” in Mallorn, vol. 58 (Winter 2017), pp. 38-41.

[17] [66] Peter Teuthold, The Necromancer, or The Tale of the Black Forest (Chicago: Valancourt, 2007), 35; originally published in 1797.

[18] [67] Ibid., 27.

[19] [68] Washington Irving, “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow [69],” 5; originally published in 1819.

[20] [70] Ibid., 29.

[21] [71] Ibid., 35-37.

[22] [72] Ibid., 39.

[23] [73] Sir Gawain and the Green Knight [74], J. R. R. Tolkien, trans., 5. The original author is unknown.

[24] [75] Ibid., 6.

[25] [76] Ibid., 9-11.

[26] [77] Ibid., 12-13.

[27] [78] Ibid., 14-15.

[28] [79] Ibid., 57.

[29] [80] Return of the King, 58.

[30] [81] Ibid., 59.

[31] [82] Ibid., 61.

[32] [83] A quote attributed to G. K. Chesterton on the nature of tradition and myth.