The Trial of the Century a Century Later

Posted By Travis LeBlanc On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled2,293 words

September 9 was the centenary of the death of Virginia Rappe at age 26.

Virginia Rappe was an actress, model, and probably a prostitute. She appeared in a few early silent films, but never became a star. She was twice engaged (once to early silent film director Henry Lehrman [2], who directed Charlie Chaplin’s first film, Making a Living), but never married. She was the illegitimate daughter of a Chicago chorus girl who died when she was 11.

She never found much success in any of her endeavors, but managed to get by the old-fashioned way — indeed the oldest fashion way — that women of her kind have used to get by throughout history. Her life was perhaps nothing to write home about, but her death rocked the world and quite possibly altered the course of history.

The trial of Rosco “Fatty” Arbuckle for the Virginia Rappe’s murder is often called “the first Hollywood scandal [4].” This is not technically true.

A year earlier, actress Olive Thomas [5] died after accidentally drinking poison. Thomas was married to actor Jack Pickford, the brother of Mary Pickford, who at the time was the second-biggest movie star in the world after Chaplin. While on vacation in Paris, Thomas and Pickford returned to their hotel room after attending a party. The very drunk Thomas than drank from a bottle of mercury bichloride, a topical solution meant to treat Pickford’s syphilis, believing that it was either water or sleeping tonic (depending on which version of the story you choose to believe). Wild speculation ensued that Thomas’ death was a deliberate suicide after learning of Pickford’s infidelity. There were even crazier theories as well, such as the idea that Pickford tricked Thomas into drinking the solution so that she could collect on the life insurance money. That was the first Hollywood scandal.

Or maybe not. I’m sure that someone out there who is an even bigger Hollywood lore nerd than I am can probably think of an earlier one. I suppose Charlie Chaplin’s penchant for marrying 16-year-olds was probably raising eyebrows as early as 1918. Or did it? Grown men marrying 16-year-olds was not exactly out of the ordinary back then. Certainly, there were stories of debauched, drug-fueled orgies in Hollywood from the very beginning. There can be no doubt that Hollywood was run by Satanic pedophiles from day one.

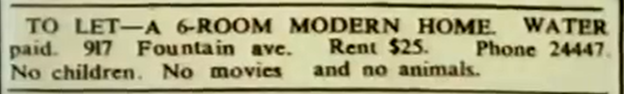

Fun fact: The term “movie” itself was originally pejorative slang invented by Hollywood townies — the people who were already living in Hollywood before the film industry arrived there — for a person who worked in the motion picture business. It was common for someone advertising a room for rent to put in their ad “no movies.” Hollywood’s original residents quickly figured out that people who worked in motion pictures had a tendency to be complete degenerates.

Thus, the Fatty Arbuckle scandal far from the first Hollywood scandal, but it was bigger than any scandal that came before it by an order of magnitude. As already mentioned, Hollywood began to acquire a reputation for degeneracy from the outset, and by 1921, there were many parties who were eager to strangle Hollywood in the crib. These included church ladies and other busybodies who, appalled by the sordid tales coming out of the burgeoning Babylon, wanted to see Hollywood fail.

There were also other cities vying to become the film capitol of America. Chicago had its own rival film industry, and films were still being made in Fort Lee, New Jersey at the time, as it had been the original movie Mecca before Hollywood. William Randolph Hearst, whose newspapers played a major role in promoting the Arbuckle scandal, had an interest in seeing the Chicago film industry prevail. The Arbuckle scandal gave these interests their chance to wage one last-ditch assault on Hollywood before it became the uncontested hegemon of pop culture.

It is a shame that the sacrificial lamb of this assault was Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle, of all people. By all accounts from people who knew him well, he was a nice guy and a perfect gentleman.

Arbuckle was born in 1887 in the town of Smith Center, a nowheresville in northern Kansas. The 1890 census records the population of Smith Center at the time as 767. Arbuckle’s father believed he was illegitimate, and as with Virginia Rappe, his mother died when he was 11. Arbuckle’s family moved to California when he was 2 years old, and he started acting in vaudeville at 9.

Arbuckle was one of the first silent film comedians. He starred in his first film in 1909, five years before Chaplin hit the scene. The year before, he had married actress Minta Derfee [8], who would later become Chaplin’s first leading lady before Edna Purviance [9] won that spot. In 1913, Arbuckle moved to Universal Pictures and then to Mack Sennet’s Keystone Studios, where he starred in many Keystone Cops films. According to legend, Arbuckle was also the first person to ever have a pie thrown in his face [10] on film (although this claim is disputed).

At Keystone, Arbuckle was frequently paired with Mabel Normand. Mabel Normand is remembered today primarily for being one of the first Hollywood junkies, and like Arbuckle, her career would also be destroyed by scandal [12] in the 1920s. Prior to that time, however, Arbuckle and Normand were popular enough of a pairing that by 1914, Arbuckle was earning $1,000 a day, which was not a bad living by today’s standards and an astronomical sum by 1914 standards.

Although his stage name was “Fatty” and was effective for marketing purposes, Arbuckle would not allow people to call him that offstage. While his comical physique was an essential part of his public image, he had enough dignity not to allow himself to be disrespected because of it.

In 1916, Arbuckle started his own production company, Comique. It was here that Arbuckle made some of his most celebrated pictures. By 1918, however, Paramount came calling with a million dollar a year contract — an offer Arbuckle couldn’t refuse. He gifted Comique to his protégé Buster Keaton and moved on to ever-greater heights.

The critics never liked Fatty Arbuckle. They considered his films to be stupid and lowbrow. However, the funny fat man was enormously popular with children. This is probably why his scandal was all the more damaging and that much more of a moral panic. Being a degenerate entertainer was bad enough, but being a degenerate children’s entertainer was beyond the pale.

By 1921, Arbuckle was on top of the world. On August 28, his film Crazy to Marry [14] was released. By Labor Day weekend, the film was still in theaters and doing good business.

To celebrate the picture’s success, Arbuckle’s friends, actors Fred Fishback [15] and Lowell Sherman [16] (who would later direct Katherine Hepburn’s Academy Award-winning performance in Morning Glory), set up a party in Arbuckle’s honor at the St. Francis Hotel [17] in San Francisco. They rented out three rooms — 1219, 1220, and 1221 — for the party. They arranged to have some booze delivered – which, as this was during Prohibition, was illegal — and to have some nice-looking and fun-loving women to attend. Arbuckle arrived at the St. Francis Hotel on September 5.

One of the women who attended was Maude Delmont. Delmont was a pimp with a long wrap sheet for prostitution and extortion. Delmont’s racket was that she would hook rich and powerful men up with pretty and morally flexible women. After these women engaged in sexual congress, she would blackmail the men with scandal and/or rape accusations unless she was paid off.

Ms. Delmont was at the party with her friend Virginia Rappe, whom she had met two days before.

Roscoe Arbuckle had been napping in his room. When he awoke, the party was well underway. What happened next is difficult to ascertain, as in the subsequent months and years, many of the witnesses changed their stories: some to exonerate Arbuckle and some to condemn him. But in the opinion of your humble author, the most likely story goes as follows.

Around 3 PM on September 5, Virginia Rappe became violently ill and began vomiting profusely. Some accounts claim that Rappe was foaming at the mouth. Most of those present believed this was the result of Rappe being drunk on illicit moonshine. In actuality, Rappe was suffering from a ruptured bladder. At one point, Rappe began tearing off her clothing. Many stated that she had a habit of taking her clothes off when drinking.

Arbuckle carried Rappe to his room and laid her down in bed, believing that she merely needed to sleep off the alcohol. Rappe would stay there for four more days, after which she was taken to a hospital, where she died on September 9.

Maude Delmont would tell the police, the press, and anyone else who would listen a very different story:

During the afternoon the party began to get rough and Arbuckle showed the effects of drinking. Virginia and I were in our room. Arbuckle came in and pulled Virginia into his room and locked the door. From the scuffle, I could hear and from the screams of Virginia, I knew he must be abusing her. . . . Arbuckle had her in the room for over an hour, at the end of which time Virginia was badly beaten up. Virginia was a good girl. She had led a clean life . . .

According to San Francisco District Attorney Matthew Brady:

Following this assault, Miss Rappe died as a direct result of the rupture of her bladder. The evidence discloses beyond question that her bladder was ruptured by the weight of the body of Arbuckle either in a rape assault or an attempt to commit rape . . . We also know that when the other members of the party went into the room, Miss Rappe was moaning in great pain and crying, “I am dying! I am dying! He killed me!”

Maude Delmont invented the rape story. Without Delmont, Arbuckle most likely never would have gone to trial. Given Delmont’s shady reputation and criminal record, prosecutors knew that she would be torn to shreds on the witness stand. It also didn’t help that telegrams Delmont sent to attorneys in Los Angeles and San Francisco surfaced which read, “WE HAVE ROSCOE ARBUCKLE IN A HOLE HERE CHANCE TO MAKE SOME MONEY OUT OF HIM.” As a result, Delmont was never called to testify at any of Arbuckle’s three trials. That did not stop her from giving numerous interviews to the press.

One partygoer, Ms. Zey Prevon, initially verified Delmont’s story, saying that she “walked into the room, Virginia was writhing on the floor, and in pain, and she said to me, ‘He killed me. Arbuckle did it.’” But a few days later, Prevon said that she actually had not seen anything and was merely repeating what Delmont had told her.

Several people who knew Rappe were willing to testify that she had a history of promiscuity and unsavory behavior, but Arbuckle refused to allow it, believing it would be disrespectful to the dead. That’s some old-school chivalry. It was not until Arbuckle’s third trial, when he was running out of money, that he agreed to allow such testimony on his behalf.

The first trial ended with the jury voting 10 to 2 for an acquittal. One of the two jurors who voted guilty was a personal friend of the District Attorney. A mistrial was declared and another trial began. That too ended in a 10 to 2 vote for acquittal. It was only after a third trial that the jury delivered a unanimous not guilty verdict.

The jury’s verdict read:

Acquittal is not enough for Roscoe Arbuckle. We feel that a great injustice has been done him. We feel also that it was only our plain duty to give him this exoneration, under the evidence, for there was not the slightest proof adduced to connect him in any way with the commission of a crime. He was manly throughout the case and told a straightforward story on the witness stand, which we all believed. The happening at the hotel was an unfortunate affair for which Arbuckle, so the evidence shows, was in no way responsible. We wish him success and hope that the American people will take the judgment of fourteen men and woman who have sat listening for thirty-one days to evidence, that Roscoe Arbuckle is entirely innocent and free from all blame.

Arbuckle was at last exonerated, but he had been destroyed nonetheless. After his merciless crucifixion in the press, his name was radioactive. He never again starred in a movie, but continued to work as a writer and director. He died in 1933 at age 46.

I previously stated that Virginia Rappe’s death possibly altered the course of history. I realize that is a bold claim, so let me make my case for it.

In response to the Arbuckle trial, Hollywood brought in Will H. Hays, the former Postmaster General, to serve as the head of the Motion Pictures Producers and Distributers of America [20]. Hays’ job was to help rehabilitate Hollywood’s reputation. He introduced various censorship regulations which would culminate in 1934 with the introduction of the Production Code [21], otherwise known as the Hays Code. The code set out an elaborate set of rules as to what could and could not appear in motion pictures: no depictions of nudity, unwed pregnancy, race mixing, and so on.

It is ironic that the Hays Code went into effect in America during the same year that the Nuremburg Laws went into effect in Germany. At heart, both were attempts to limit Jewish influence in society. The Production Code would remain in effect until 1968, when it succumbed to pressure from foreign films, television, and the courts. But if it hadn’t been for the Production Code, American culture and society might have been where it is now back in the 1980s. And it all began with Virginia Rappe.