“A Kinges Ransoume” for a “Croune of Paper”: Charisma in Pre-Modern Europe, Part I

Posted By Kathryn S. On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledPart 1 of 3 (Part 2 here [2])

Dual Charismatic Cycles of the West

“Heed my words all classes of men, you greater and lesser children of Heimdall”: When all “the gods went to their thrones, those holy, holy gods,” they came to a decision. They would make leaders from “Ymir’s blood and his rotting limbs.” Above the world would grow “an ash tree, named Yggdrasil, a high tree, speckled with white clay; dewdrops falling from it upon the valleys.” It will stand, “forever green, above Urth’s well,” and all will seem good.

But then will come a darkness: “I see oathbreakers wading in” the thick streams of the blackened river, “and murderers, and those who seduce others’ lovers. There Nithogg” will feast on “the corpses of the fallen,” and devour them in his jaws. Fenrir, the wolf, will howl “terribly before the doors to Hel,” and one day he “will break its bonds and run . . . a dark day for the gods. Brothers will fight one another and kill one another, cousins will break peace . . . the world will be a hard place to live in . . . it will be an age of the axe, an age of the sword, an age of storms, an age of wolves.” And before “the world sinks into the sea” at last, “there will be no man left who is true to another . . . a dark day for the gods.” But you higher and lower sons of the All-father, I see too, “the earth [rising] a second time from out of the sea, green once more . . . Waterfalls [flowing] . . . among the mountain peaks . . . Balder will come back [and] will live in Odin’s hall”; the dragons will keep to their cliffs, while the wolves will hide in their caves.

These first verses from the Norse Edda revealed a cyclical fate for the universe and all its creatures — a cosmology endowed with a life-spark born of the omnipresent charisma and, sometimes, even the blood of the gods.[1] [3]

And what is charisma but a gift of grace that justifies leadership — instills within a will to command and exerts without a compulsion to obey? And there are different types of charisma: “pure charisma,” the kind most often associated with the word, is a personal magnetism that draws people to an individual and inspires obedience and loyalty within the breasts of the charismatic’s followers. “Lineal/office charisma” is often the next stage of “pure charisma,” where grace manifests through bloodlines and offices — the process of succession that broadens (and dilutes) an individual’s charisma and bestows it on the rulerships and the men who come after him.[2] [4] All the modifications of the former to make the latter have the same cause: “[t]he desire to transform charisma and charismatic blessing from a unique, transitory gift of grace of extraordinary times and persons to a permanent possession of everyday life.”[3] [5] Aristocracies and Church appointments were examples of these, for they represented an institutionalization of charisma in which tradition and stability, rather than inspirational fire, were used to lead societies. And as soon as “pure,” personal charisma became one of blood, then it became lineal.

When Christ shed His blood and became a messianic martyr, His pure charisma, pure grace, transferred to the apostles through the Holy Ghost and its “tongues of fire.” Saint Peter’s sacrifice contributed to this blood-charisma and infused the Church of Rome with an institutional mission of imperium. The Church was never so strong as when the blood of martyrs and the mesmerism of the saints inspired whole nations to resist or convert. In order to be most effective, lineal charisma needs this occasional dram of rejuvenating heroes’ blood. And at the heart of all aristocracies there was this kind of magic — blood magic, too. At some point in the past, a personality like Æneas, Tamerlane, William of Normandy, or Thor Odin-son united his followers and conquered wide lands; the rulers and peers of the realm then claimed descent from these legendary kings and the deeds of those whom they entrusted with their mission. Aristocracy was the very essence of purity transformed into lineal: the reanimation of Ymir’s “blood and rotting limbs”; the metaphor of the family tree, of gray, “speckled” Yggdrasil as it saturated the vales with its holy water. One’s exalted genealogy consecrated the nobleman with the right to direct armies and safeguard kingdoms.

[6]

[6]You can buy Kerry Bolton’s More Artists of the Right here. [7]

Whether of the pure or lineal variety, charisma aimed at capturing the imagination and keeping the loyalty of a nation’s people — of binding them to a communal vision of glory, heroism, and ancient myth. It was an investiture of grace made manifest. This explained the literal vestments of priestly habits, heraldic colors, and family crests; orbs and mitres, anointing oils, the miraculous healing power of the prince’s robe as he brushed past trailing fingertips; the medieval ceremony of the accolade, when the touch of a monarch’s blade conferred knighthood and nobility upon a worthy subject. Physical expressions of abstract, charismatic leadership, all.

But when these different charismas have clashed rather than synced, whole worlds have shaken and entire epochs upended. The rise of a pure charismatic signalled the decay of an older lineal charisma whose power had bled itself out, its age of glory and gods sunk into decadence. A “routinization” had made it stale. Whenever history has remembered a salvific hero, tyrant, or traitor, they have usually emerged from such conflicts. The pure charismatic, who, paradoxically, always called upon lineal charisma and his own bloodline to justify his challenge to the ancien régime, was a spiritual and/or military conqueror, able to whip the commons into a passion. Meanwhile, the institutions he confronted were staffed by elite oligarchs, whose leadership they inherited through blood or office. The bureaucracies the latter group led were fusty and corrupt: an impoverished charisma made them ornamental leaders clinging to ceremony and little else.

By analyzing several examples from pre-modern Europe, I see a pattern that persisted through the millennia. Those “dark days” had deadly consequences and presented moments of transition in a cyclical fashion: the flame of a charismatic idol briefly burned as the “sunne in splendour,” then faded to the calmer taper light of a charismatic tradition that endured on the bases of blood and memory.[4] [8] They each touched on the West’s unique preoccupation with tyranny, its definition and its prevention. Fortunately for poetry’s sake, each trial had its Shakespearean correlative, as well as a host of other tales, whose authors have represented them in historical chronicles and fictional myth. I have chosen not to distinguish between the two sorts of stories, because no line separates the one definitely from the other, and for the aims here, their distinction is irrelevant. There is, finally, the inescapable question for the present: O, Europa, “hath love in thy old blood no living fire” left?[5] [9]

“The Greatest of the Greeks”: Alcibiades vs. Athens

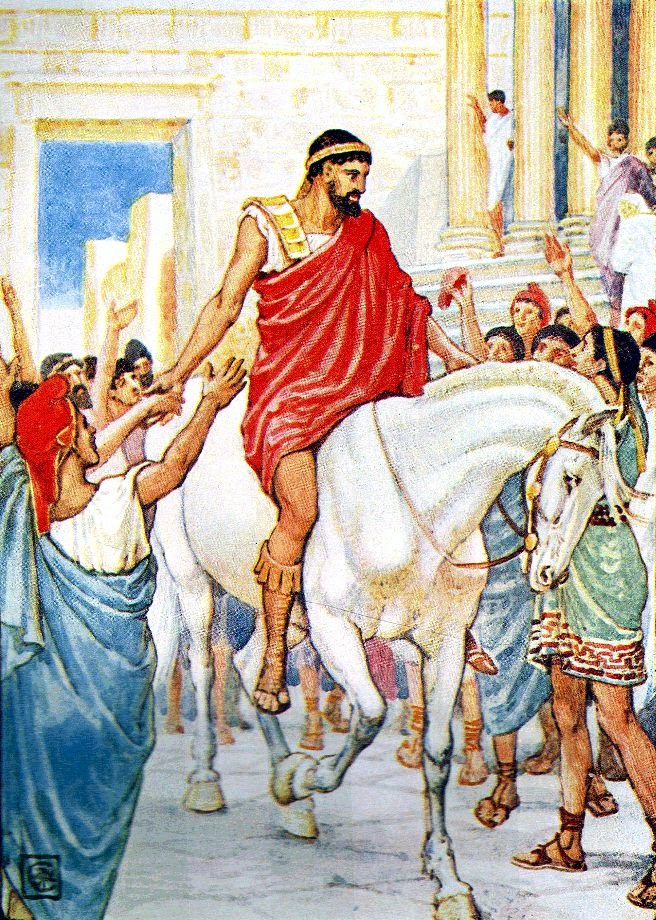

[10]

[10]“When he landed, people . . . ran in throngs to Alcibiades with shouts of welcome, escorting him on his way, and putting wreaths on his head,”[6] [11] The Return of Alcibiades to Athens, unknown artist

The nighttime assassins sent to kill him surrounded his house and set it ablaze.

“Now this was the engagement in which I received the prize of valour . . . which the generals wanted to confer on me, for I was wounded . . .”

Winding his cloak about his left arm as a shield and holding his dagger aloft with the other, he dashed out from the flaming ruins to meet his attackers.

“He who opens the bust [of Socrates] and sees what is within will find that they are the only words which have a meaning in them . . . extending to the whole duty of a good and honourable man.”

Waiting some distance away, the assassins shot him with javelins and arrows.

“The aim [of good counsel] is the better order and preservation of the city.”[7] [12]

Thus he fell in a dark and dirty alley far away from home and with only his grieving mistress to care for his body

The interchanging lines above were spoken by and about the same man, whose love of Athens clashed with his love of self and vainglory. Fifth-century Athens was a democracy with a seemingly insoluble problem: Its society instilled within the breasts of its citizens the double-sided values attached to thumos. Among its menfolk, a deeply felt “public-spiritedness” nourished aspirations of becoming great statesmen and public servants; it also encouraged a love of glory and a lust for power which at times exceeded devotion to honor and community, becoming destructive of them both.[8] [13] If this dilemma had a name, it would have been Alcibiades of Alcmaeonidae. His pure charisma galvanized — and alienated — the entire Mediterranean world, leading Plutarch to call him: “the greatest of the Greeks.” High praise for a man living during an age conspicuous for its wealth of remarkable men.

Here was a youth who had everything. Alcibiades came of age in the greatest city of the ancient world and at the height of its grandeur. He was a rich, talented, and handsome celebrity there. “Joy was it at that season but to live.” Notorious for debauchery, Alcibiades “was very much in the public eye, and his enthusiasm for horse-breeding and other extravagances went beyond what his fortune could supply.”[9] [14] Indeed, “most people became frightened at a quality in him which was beyond the normal and showed itself both in the lawlessness of his private life and habits and in the spirit in which he acted on all occasions.” The reputable “men of the city looked on all these things with loathing and indignation . . . They thought such conduct as his tyrant-like and monstrous.”

[15]

[15]You can buy Collin Cleary’s Wagner’s Ring & the Germanic Tradition here. [16]

Shrugging off the disquiet of others, Alcibiades explained breezily that “it [was] quite natural for [his] fellow citizens to envy [him] for the magnificence with which [he had] done things in Athens.” He had made a “splendid show” at the previous Olympic Games, during which he’d entered seven chariots for the chariot race (more than anyone had before him). Naturally, he “took the first, second, and fourth places, and saw that everything else was arranged in a style worthy of [his] victory.”[10] [17] He seemed to be of the opinion that without Alcibiades, Athens would be a dull frontier town, only fit for a population of water-hewers and ditch-diggers rather than the mightiest force in the Mediterranean. His ambitions were bound up in the ambitions of the city, both man and polis reinforcing one another’s imperialist designs. For Golden Age Athens and her golden boy, the world was not enough.

When war broke out between Athens and Sparta in 431 BC, Alcibiades’ native city-state harnessed the extraordinary “quality” of his that set him above all others of his generation. His arrogant patriotism demanded that he be appointed to military leadership despite his youth, for, he argued, “I have a better right than others to hold the command, and I think I am quite worthy of the position.” Rest assured, fellow-citizens, I only desire “things which bring honour to my ancestors and myself, and to our country’s profit as well.”[11] [18] Here, Alcibiades exercised a pure charisma of personality by cleverly appealing to his lineal charisma of blood-ancestry. The contradictory argument he made would have had the people discard the traditions favoring maturity and embrace the zeal of his youth — in order to please the elders, of course.

The beginning of Alcibiades’ downfall, and thus the downfall of Athens, occurred a few nights before he, his fellow-commander Nicias, and a huge armada of triremes were to set sail for the conquest of Sicily — an island on which “the Athenians had cast longing eyes” for decades. It was Alcibiades who “fanned these desires into a flame,” and convinced the commons to subdue it utterly. Over the years, he’d proven to be a brilliant general and was responsible for dazzling victories. His aura of invincibility “persuaded the people to have great hopes . . . he himself had greater aspirations still.” Indeed, he “regarded Sicily as a mere beginning, and not, like the rest, as an end of the expedition.” While Nicias was trying to divert the people from the capture of Syracuse (a major city on the Sicilian island) as an undertaking too difficult for them, Alcibiades was “dreaming of Carthage and Libya, and, after winning these, of at once encompassing Italy and Peloponnesus.”[12] [19]

By contrast, Nicias was not a man possessed of pure charisma, nor did he enjoy the erotic allure with which Alcibiades’ beauty enchanted all those whom he met. Instead, people gravitated toward Nicias because of the lineal charisma that connected him to the generations of the past. He cast wary eyes upon the hungry young man seated some distance away and delivered a speech to the throng gathered at the Athenian assembly. “Beware of” Aliciades, he warned, “and do not give him the chance of endangering the state” so that he might “live a brilliant life of his own. Remember that” the expedition “is an important matter, and not the sort of thing that can be decided upon and acted upon by a young man in a hurry . . . I, on my side, call for the support of the older men among you.”[13] [20] Lacking the vitality that powered Alcibiades’ lust for revolutionary command and empire, Nicias was a man of old Athens. As such, he appealed to the elder oligarchs of the state, who were charged with cherishing and safekeeping the institutions left behind by generations gone.

Then, Alcibiades took the floor. He was unmatched in his eloquence. In a striking description of Sicily that would describe the West’s future, he charged that “[t]he Sicilian cities have swollen populations made out of all sorts of mixtures, and there are constant changes and rearrangements in the citizen bodies. The result is that they lack the feeling that they are fighting for their own fatherland.” Our fathers meanwhile “had the Persians on their hands . . . and so founded the empire . . . Do not be put off by Nicias’ arguments for non-intervention . . . Let us instead keep to the old system of our fathers who joined together in counsel, young and old alike, and raised our state to the position it now holds.” So make it your endeavor to raise this city to even greater heights, he preached. Remember, too, “that the city, like everything else, will wear out of its own accord if it remains at rest.”[14] [21] Alcibiades’ contradictory charismas and captivating glamor carried the day.

The clash of charismas that Alcibiades’ rise in Athens represented came into no sharper focus than it did during the infamous Hermae affair. Decorated with the heads of the ancestors atop and their phalluses below, Hermae were sacred stone pillars and the incarnation of Athens’ past that bestowed grace and luck on those of the present. Of course, the phalluses symbolized the literal and metaphorical seed that had germinated and flourished in Athens and through the Athenians’ ancestry — lineal-charismatic blood worship. A week before the Sicilian expedition was set to commence, a few nighttime carousers cleaved off the noses and genitalia of the Hermae throughout Athens. People took it badly. In no mood for practical jokes, “the multitude . . . looked on the occurrence with wrath and fear, thinking it the sign of a . . . dangerous conspiracy.”[15] [22] Because of his universally known penchant for reckless and irreverent behavior, Alcibiades found himself the target of Athenians’ suspicion. In a calculated decision, the assembly chose not to try him for heresy before he left on the journey, and decided instead, “Let him sail now, and God be with him! But when the war is over let him come and make his defense. The laws will be the same then as now [a curious assumption to make for a notoriously fickle democracy].”[16] [23]

Incensed at the Senate oligarchs’ faithlessness, Alcibiades became what they’d always feared: no more the savior, he was determined to prove the villain. “Now the gods keep you old enough that you may live / Only in bone,” he spat. While Alcibiades “kept back their foes . . . [the senators] . . . let out / Their coin upon large interest.” As for himself, he was “Rich only in large hurts. All those for this? / [Was] this the balsam that the usuring Senate / [Poured] into captains’ wounds? Banishment. It [came] not ill,” for “It [was] a cause worthy [of his] spleen and fury, / That [he] may strike at Athens. / I’ll cheer up / My discontented troops,” he swore, “and lay for hearts.”[17] [25]

The old men of Athens had betrayed him, so Alcibiades became a traitor himself and defected to the Spartans. Because he knew that “his troops” would follow him, he planned to use his pure charisma to destroy the Athenian city-state and the lineal patronage that upheld a stifling regime there. His promise to “lay for hearts” referred both to his winning ability to capture and retain the loyalty of his people, and a threat to kill his enemies by carving out the hearts from their unmanly chests. For the next several years and in the name of his wounded honor, Alcibiades plundered the Athenians on the Aegean and in the Attica bushland. Still, he dreamed of home. In 411 BC, the Athenian allies whom he’d carefully cultivated over a number of months invited him to return to the city and his military post. The crowds met him with jubilation, “crown[ing] him with crowns of gold, and elected him general with sole powers by land and sea.”[18] [26]

But it was not to last.

After renewing the devastating war with the Spartans and rejecting their overtures of peace, Alcibiades proceeded to anger the oligarchs once again. The charismatic man of many faces spent his final days in an obscure backwater, where his assassins finally caught up to him. According to Plutarch, visions disturbed his sleep. He dreamed that he had his mistress’ “garments upon him, and that she was holding his head in her arms while she adorned his face like a woman’s with paints and pigments.” He saw man-hunters “cutting off his head and his body burning.”[19] [27] He feared that, like his fathers before him, his fiery blood would become a vein of effeminate desiccation through death. By the end of the night, Alcibiades suffered the customary fate of unconventional leaders: He bled out in a foreign corner of the world as Athens succumbed to her enemies. In life, his volatility matched that of his homeland — a democratic state easily swayed by demagoguery; a city whose violent rages could condemn to death its best warriors and greatest thinkers, and make their executions seem like wisdom. This charismatic clash of the fifth century ended the Greek era. Meanwhile, somewhere in the foothills of Phrygia, Alcibiades’ “old bones” still lay unclaimed by his countrymen.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Notes

[1] [28] The Poetic Edda, Jackson Crawford, ed. (Indianapolis: Hackett, 2015), 2-16.

[2] [29] I take as a reference point German sociologist Max Weber’s theory of charisma, as well as his disciple Raphael Falcone and his “Charismas in Conflict: Richard II and Henry Bolingbroke” in Exemplaria vol. 11, no. 1 (1999), pp. 473-502.

[3] [30] Falcone, 476.

[4] [31] The “Sunne in Splendour” was the name given to Edward IV after a rare phenomenon known as a “parhelion” brightened the sky before he went on to win a great victory during the Wars of the Roses.

[5] [32] Take from a quote by the Duchess of Gloucester in William Shakespeare’s Richard II, I.ii., 10 (Folger Shakespeare Library Online [33]).

[6] [34] From Plutarch, “The Life of Alcibiades [35],” in Parallel Lives (London: Loeb Classical Library, 1916).

[7] [36] Each of the italicized words are from Plato’s Symposium [37], Rhonda L. Kelley, ed.

[8] [38] See Steven Ford, The Ambition to Rule: Alcibiades and the Politics of Imperialism in Thucydides (London: Cornell University Press, 1989).

[9] [39] Thucydides, The Landmark Thucydides, Robert B. Strassler, ed. (New York: Free Press, 1996), 202.

[10] [40] Ibid., 203.

[11] [41] Ibid., 202.

[12] [42] Plutarch, “The Life of Alcibiades.”

[13] [43] Thucydides, 202.

[14] [44] Ibid., 203.

[15] [45] Plutarch, “The Life of Alcibiades.”

[16] [46] Ibid.

[17] [47] William Shakespeare, Timon of Athens [48] (Folger Shakespeare Library), III. v. 112-125.

[18] [49] Plutarch, “The Life of Alcibiades.”

[19] [50] Ibid.