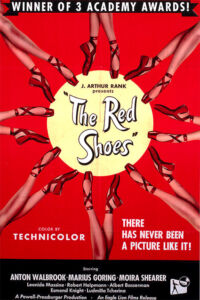

The Red Shoes

Posted By Trevor Lynch On In North American New RightMichael Powell’s The Red Shoes (1948) is his greatest work and one of my all-time favorite films. The Red Shoes is a work of art about art. Its central characters are ballet impresario Boris Lermontov (brilliantly played by Anton Walbrook), ballerina Victoria Page (acted and danced by Moira Shearer), and composer Julian Craster (Marius Goring, who was much too old for the role and looks ridiculous smoking a cigarette but is otherwise adequate).

Page and Craster are young talents who are drawn into the creative vortex of Lermontov’s company, rise quickly to stardom, then fall in love with one another and fall out with Lermontov. A happy ending seems, however, to be in the offing until the screenwriter contrives a perversely tragic finale in which Vicky Page dies. Both Lermontov and Craster live on, but they are utterly destroyed as human beings.

The Red Shoes doesn’t just dance around its subject — focusing on personalities, the creative process, and backstage romance — it actually puts ballet on the screen, most spectacularly in the form of a seventeen-minute original ballet based on Hans Christian Andersen’s fairytale “The Red Shoes,” with music by Brian Easdale, set design by Hein Heckroth, and choreography by the great Robert Helpmann and Léonide Massine, who also dance in the ballet and play the roles of Ivan Boleslawsky and Grischa Ljubov in the film.

The core of The Red Shoes is the character of Boris Lermontov, loosely based on the great Russian ballet impresario Sergei Diaghilev and unforgettably brought to life by Anton Walbrook. Lermontov is brilliant, charismatic, and utterly devoted to ballet, which he regards as his “religion.” He can be domineering, autocratic, brooding, and sometimes brutally frank. But his most outstanding traits are the elegant manners, sensitive diplomacy, and affectionate fatherliness with which he manages his team of highly-strung and egotistical artists.

A great deal of the charm of The Red Shoes is watching Lermontov’s creative family in action: Page, Craster, and Grischa as well as designer Sergei Ratov (played by the great German actor Albert Bassermann) and conductor Livingstone “Livy” Montague (played by Esmond Knight). Each day ends as one by one they bid him a fond “Goodnight, Boris.”

Two of the best scenes — where Craster rehearses an orchestra, correcting a wrong note in the process, and where he introduces his original music for The Red Shoes ballet — were actually based on episodes in the process of creating the movie itself.

The Red Shoes is about the relationship between art and life. Early in the film [2], they are likened to one another, because they are both compulsions:

Lermontov: Why do you want to dance?

Vicky: Why do you want to live?

Lermontov: Well, I don’t know exactly why, but I must.

Vicky: That’s my answer, too.

But if art and life are both compulsions, then they can conflict with one another. Even in the best of circumstances, artistic excellence can only be achieved by dominating the body and its desires, sublimating some, suppressing others. As Lermontov puts it, artistic excellence can only be achieved by a “great agony of body and spirit.”

But beauty and excellence can easily become all-consuming obsessions that don’t just dominate life but destroy it, a danger represented by the red shoes. In one of the best scenes in the movie [3], Lermontov summarizes the story of The Red Shoes ballet to Craster, who will compose the music:

The ballet of The Red Shoes is from the fairy tale by Hans Andersen. It is the story of a girl who’s devoured by an ambition to attend a dance in a pair of red shoes. She gets the shoes, goes to the dance. At first, all goes well, and she’s very happy. At the end of the evening, she gets tired and wants to go home. But the red shoes are not tired. In fact, the red shoes are never tired. They dance her out into the streets. They dance her over the mountains and valleys through fields and forests, through night and day. Time rushes by. Love rushes by. Life rushes by. But the red shoes dance on.

https://youtu.be/t1ga6wgQjNU?t=2347

Lermontov is practically in a state of rapture when he completes his synopsis.

“What happens in the end?” asks Craster.

“Oh, in the end, she dies,” says Lermontov, as if it were an afterthought.

The Hans Christian Andersen tale is more about sin and addiction to sensual pleasures, whereas in the film the red shoes represent the sacrifice of life to the obsessive pursuit of beauty.

Later in the film, after the successful debut of The Red Shoes ballet, Lermontov explains his ambitions for her career and offers Vicky a Mephistophelean choice:

Lermontov: I want to create, to make something big out of something little, to make a great dancer out of you. But first, I must ask you the same question: What do you want from life? To live?

Vicky: To dance.

Near the end of the film, Lermontov comforts a heartbroken Vicky with the words, “Life is so unimportant” — unimportant compared to art, that is.

Part of life is love, marriage, and family. Lermontov is particularly dismissive of ballerinas who allow these considerations to interfere with their art. First, it leads him to dismiss his prima ballerina Irina Boronskaja (Ludmilla Tchérina):

I’m not interested in Boronskaja’s form anymore . . . nor in the form of any other prima ballerina who’s imbecile enough to get married. . . . She’s out, finished. You cannot have it both ways. The dancer who relies upon the doubtful comforts of human love will never be a great dancer. Never.

(This episode seems to be based on Diaghilev’s decision to fire Vaslav Nijinsky when he got married.)

Lermontov then begins to groom Vicky to replace Boronskaja. When Lermontov learns that Vicky and Julian have fallen in love, he tries to break them up, driving Craster to quit on the assumption that Vicky will stay. But instead she leaves as well.

It is tempting to believe that Lermontov was acting out of sexual jealousy. His body language with Vicky in one scene [4] is quite intimate. Also, before he learns of Vicky’s relationship with Craster, he seems to wish to ask her on a date, although it may simply be to discuss business. Earlier in the film, Vicky thinks that Lermontov has invited her on a date, which she eagerly accepts, dressing up like a princess. But it turns out to be just a business meeting. Only when it becomes apparent that Lermontov is entirely focused on his work does she notice Craster. Craster accuses Lermontov of jealousy. He agrees, but says it is not sexual. He may be telling the truth. After all, there’s no hint of sexual interest in Boronskaja, yet he rejects her for getting married as well. It might indeed be just about his single-minded devotion to ballet.

In another brilliant, brooding scene [5], Lermontov comes to the realization that he has been a fool. (Note that Lermontov, always the impresario, adjusts the lighting, finds his mark, and assumes a pose before inviting people into a room.) Then Lermontov decides to approach Boronskaja, who is still happily married, and lure her back on stage. Boris has obviously concluded that art and life — in particular, married life — need not conflict. A year later, he manages to lure Vicky back on stage to dance The Red Shoes again.

Then Emeric Pressburger’s script goes seriously off the rails — or, rather, the red shoes dance the story off a balcony and onto the rails. The original Andersen tale has a gruesome end. The girl, unable to take off the red shoes, asks the executioner to chop off her feet, which go dancing off in the red shoes. The girl, thus freed of sin, ends up going to heaven, which is a happy ending of sorts.

Fixated on contriving an ending that is both gruesome and unhappy, Pressburger simply forgets about Lermontov’s character development toward accepting that his ballerinas can have private lives. He also turns Julian Craster into a petty, jealous villain — something not foreshadowed in the least. Then they drive Vicky to suicide.

The whole setup is absurd. Vicky has come to Monte Carlo on vacation. On the spur of the moment, she agrees to dance The Red Shoes again. We are asked to believe that Craster’s new opera is to premiere in London the same day that Vicky dances The Red Shoes again in Monte Carlo. Why was Vicky in Monte Carlo on her husband’s big night?

Then we are asked to believe that Craster leaves his premiere and travels all the way to Monte Carlo on the suspicion that his wife will be on stage again. He shows up in her dressing room to the sound of villainous music, dressed in a black leather trench coat (in Monte Carlo, in the summer). Is Julian a Nazi now? Then he demands that she return with him that very moment to London without going on stage.

Vicky refuses. Julian storms out. Lermontov villainously exults in triumph. Then Vicky, who is trying on the red shoes for that night’s performance, goes mad and hurls herself off a balcony, and then gets hit by a train. The train seems like overkill, but there’s still enough life in her to beg a distraught Julian — who just happened to see her plunge to her death, even though it would have been impossible from his vantage point — to take off the red shoes.

I can’t think of a more arbitrary, ramshackle, and dissatisfying end to an otherwise great movie. It is a testimony to just how good the rest of the film is that viewers put up with it.

When the producers of The Red Shoes saw the finished film, they thought they had an expensive flop on their hands and decided to cut their losses by stinting on the premiere and promotion in the United Kingdom. However, the film became a hit in the United States, largely due to word of mouth and a few independent theatre owners who loved it. The Red Shoes ended up nominated for five Academy Awards, winning for its music and art direction. It went on to be one of the highest-grossing British films ever.

Initial reviews were tepid and desultory, but the film’s reputation among filmmakers and critics has grown steadily over the years. It is widely hailed as a masterpiece and included in many “best of” lists.

Despite the flawed ending, there are many reasons why I return to The Red Shoes again and again: Michael Powell’s extraordinary visual imagination, the colorful characters and outstanding cast that bring them to life, cinematographer Jack Cardiff’s lush Technicolor, Brian Easdale’s vivid music, the dazzling ballet sequences, and the glimpses of London, Paris, and Monte Carlo before the fall, which provoke nostalgia for a world I have never known.

But above all, I love The Red Shoes as a portrayal of the world of European high culture: an aristocratic, inegalitarian world devoted to the pursuit of beauty and excellence — a world whose basic principles contradict those of democracy and mass commercial entertainment. Try it for the entertainment. You’ll stay for the art. And some of you will return out of obsession.

The Unz Review, August 23, 2021 [6]

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here: