Every Day is Thursday

Posted By Spencer J. Quinn On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledSyme had for a flash the sensation that the cosmos had turned exactly upside down, that all trees were growing downwards and that all stars were under his feet. Then came slowly the opposite conviction. For the last twenty-four hours the cosmos had really been upside down, but the capsized universe had come right side up again.

When you flip reality and its opposite enough times, it’s hard to determine which is which. G. K. Chesterton demonstrated this beautifully in his 1908 novella The Man Who Was Thursday, and now, over a century later, this very same illusion is being played out in current events. In this dreamlike fantasy, we have Gabriel Syme, a British police detective posing as a poet who’s in turn posing as an anarchist, who meets Lucien Gregory, an anarchist posing as a poet who’s posing as an anarchist. So everything isn’t as it seems—only it is, since Gregory is part of a secret criminal cabal of anarchists who disguise themselves as dandies and who dabble in anarchism. Hiding in plain sight, so to speak.

After some strife with Gregory, Syme infiltrates this cabal, which is run by a mysterious and massive superhuman named Sunday. There are six anarchists in his inner circle, each named for a day of the week, with our protagonist having recently been promoted to the position of Thursday. They are plotting the assassination of both the Tsar and the French President who will soon be meeting in Paris. The weapon, they decided, would be a bomb.

We should remember that when this was written, bomb-throwing anarchists had already made a big impact on the times. Tsar Alexander II had survived several assassination attempts before succumbing to a bomb attack in 1880. The same was true of Russian Prime Minister Pyotr Stolypin, although he wouldn’t meet his end until 1911. Prior to that, a bomb attack had crippled one of his daughters. And of course, US President William McKinley had been assassinated by an anarchist (although only a gun-wielding one) in 1901. See Joseph Conrad’s brilliant The Secret Agent for more about how the specter of anarchism had captured the Western mind back then, especially in England.

As Thursday worms his way through the anarchist underworld, we never lose sight of the ubiquitous reality reversal which characterizes Chesterton’s settings and characters. Opposites abound in The Man Who Was Thursday. Despite being a detective, Syme is not from a respectable family, but from “a family of cranks, in which all the oldest people had all the newest notions.” Hilariously, as his mother rebelled against tradition through strict vegetarianism, his father rebelled against her nearly to the point of defending cannibalism. It is against this culture of rebellion that young Syme rebelled and became a police detective, dead set on stamping out one kind of rebellion for the sake of another. And his bête noire of rebellion was indeed anarchism.

But Chesterton makes it clear that Syme’s rebellion is more necessary and truthful than its opposite. At least, that’s how it reads a century later, as the Left tightens its tentacles all over the West. Today, Chesterton’s words resonate like a clarion call. Early on, Syme meets a philosopher policeman (one of the novel’s many contradictions), who says:

We say that the dangerous criminal is the educated criminal. We say that the most dangerous criminal now is the entirely lawless modern philosopher. Compared to him, burglars and bigamists are essentially moral men; my heart goes out to them. They accept the essential idea of man; they merely seek it wrongly. Thieves respect property. They merely wish the property to become their property that they may more perfectly respect it. But philosophers dislike property as property; they wish to destroy the very idea of personal possession.

Later, the policeman explains:

They also speak to applauding crowds of the happiness of the future, and of mankind freed at last. But in their mouths . . . these happy phrases have a horrible meaning. They are under no illusions; they are too intellectual to think that man upon this earth can ever be quite free of original sin and the struggle. And they mean death. When they say that mankind shall be free at last, they mean that mankind shall commit suicide. When they talk of a paradise without right or wrong, they mean the grave.

This prescient policeman also predicts how “. . . a purely intellectual conspiracy would soon threaten the very existence of civilization,” and how “. . . the scientific and artistic worlds are silently bound in a crusade against the Family and the State.”

So in The Man Who Was Thursday we have pernicious philosophers, mendacious scientists, and degenerate artists set on destroying civilization. One hundred years on, is Chesterton wrong?

In the book, we also have natural landscapes looking quite unnatural (“. . . as of that disastrous twilight which Milton spoke of as shed by the sun in eclipse . . .”). We have the mundane details of London appearing as inexplicable elements of alien cultures. We have the common noises of animals in the zoo sounding like baying beasts in Hell. We have a large mass of people moving as if they were one man. We have ordinary citizens who in an instant become gun-wielding terrorists.

More bizarre are the anarchists themselves. At the great meeting with Sunday to plot the Paris bomb attack, Syme notes how they all seem normal and healthy, even fashionable. Yet he soon spots idiosyncrasies which reveal some “demoniac detail” about each of them. One has a face of classic beauty which is marred by a crooked smile. Another has a black beard which, upon close inspection, appears rather a dark shade of blue. Another is so old, it appears as if “some drunken dandies had put their clothes upon a corpse.” Another wore sunglasses so dark that Syme was reminded of stories in which coins were placed over the eyes of the dead.

Creepy stuff. But none creepier than Sunday himself, whom Chesterton presents as an amoral, all-knowing, and gigantic demigod. Syme reports how at first he could not see him sitting at a balcony overlooking the street because he was “too large to see”:

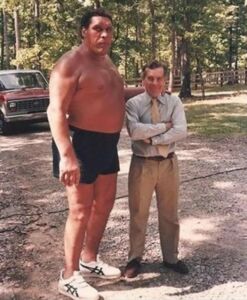

This man was planned enormously in his original proportions, like a statue carved deliberately as colossal. His head, crowned with white hair, as seen from behind looked bigger than a head ought to be. The ears that stood out from it looked larger than human ears. He was enlarged terribly to scale; and this sense of size was so staggering, that when Syme saw him, all the other figures seemed quite suddenly to dwindle and become dwarfish.

The only analog I can imagine to convey the terror Syme must have felt in the presence of such a being is that of pro-wrestler Andre the Giant.

When I see the Big Show or the Undertaker or some other pro-wrestling behemoth, I see a tall human being with big muscles. When I see Andre the Giant, especially in the above photograph, I see something else entirely. I see something that is both proto-human and superhuman. “Enlarged terribly to scale,” indeed. And it is terrifying. Absent Andre’s wide, disarming smile, his stylish 1970s and ‘80s attire, or the circus-like pro-wrestling milieu in which he thrived—all of which link him to humanity—I would have to fight the urge not to be terrified when gazing upon this gargantuan man.

So imagine Andre the Giant with a 200 IQ and the weird ability to warp reality and manipulate men’s minds, and you have the man who was Sunday.

As if this weren’t enough, Syme then discovers something utterly shocking. One of the other anarchists, Tuesday to be precise, is also a police detective. Same with, as Syme eventually discovers, all of the others. Six anarchists, six impostors. So this adds an additional layer of reality (or unreality) to these men and the law and order they are supposed to represent. Does Monday still have a crooked smile? Is Wednesday’s beard still blue?

When in France, the detectives are set upon by a large mob. They fear that Sunday had learned their true identities and is sending men to silence them forever. They understand that only Sunday, the supernatural anarchist, has the wide-ranging power and influence to not only attack them in another country, but to cause the local populace and the gendarmes to rise up against them as well. The detectives cannot believe it. How can so many ordinary Frenchmen be radicalized to anarchy so quickly? What has happened to tradition, religion, common sense?

In one of the most apocalyptic chapters I have ever read, called “The Earth in Anarchy,” Chesterton writes:

That town was transfigured with uproar. All along the high parade from which they had descended was a dark and roaring stream of humanity, with tossing arms and fiery faces, groping and glaring towards them. The long dark line was dotted with torches and lanterns; but even where no flame lit up a furious face, they could see in the farthest figure, in the most shadowy gesture, an organized hate. It was clear that they were the accursed of all men, and they knew not why.

Soon after, we get this exchange between the optimist Saturday (whose name is Bull) and the pessimist Wednesday (known as the Inspector):

“Nonsense!” said Bull desperately; “there must be some people left in the town who are human.”

“No,” said the hopeless inspector, “the human being will soon be extinct. We are the last of mankind.”

How many of us felt this way during the summer of 2020? How many of us still feel this way a year later during the Biden administration? We’ve seen mobs and mobs of Leftists (today’s equivalent of anarchists) riot in the streets, burn cities, terrorize citizens, intimidate police, declare sovereignty, and utterly destroy all who oppose them. Further, they got away with all of it while our leadership and media either make excuses for them or deny they even exist.

“We are the last of mankind.” Why, yes. Yes, we are.

We are now trapped in a world eerily similar to the dreamscape found in Chesterton’s The Man Who Was Thursday. What’s down is up and what’s up is down. Everything is flipped on its head these days. Truth is forbidden while falsehoods abound. George Floyd died of an overdose in police custody, and the Left lionizes him has a social justice martyr. Antifa and Black Lives Matter stage “mostly peaceful protests” which cost dozens of lives and billions in damages, yet the Left calls the one-day event at the Capitol on January 6 a riot and an insurrection. The Left steals the presidential election in the dead of night and then censors and attacks anyone who speaks out against it. As a result, we have a fake president, fake vice president, and fake attorney general. We have fake borders which let in fake Americans. We have a fake Supreme Court which would not even consider a case brought forth by a sitting US President. We have a fake educational system which pushes fake social justice and fake critical race theory on students. We have fake women and fake men demanding we address them by their fake pronouns. And now we have a fake vaccine for a fake pandemic that our fake government wishes to force on everyone.

And half of the country believes that what is fake is real! Not only this, but people risk getting censored, deplatformed, doxxed, or worse if they stand up to all the lies.

How is it that we’re not living in G. K. Chesterton’s imagined world?

What drew me to this book at this particular time was the revelation of another act of fakery on the part of our government. This one is so egregious that it approaches in reality what G. K. Chesterton had assigned to fantasy. In October 2020, the FBI foiled a plot by “Right-wing extremists” to kidnap and perhaps execute Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer. Well, last month Buzzfeed [3] revealed that the FBI had employed at least twelve confidential informants in order to nab six suspects—five of whom are putting in not-guilty pleas and claiming they were set up. One is claiming entrapment. They also claim that some these informants had been among the ringleaders [4] all along:

One informant from Wisconsin allegedly helped organize meetings where the first inklings of the plot surfaced, even paying for hotel rooms and food to entice people to attend, Buzzfeed News reported.

Another undercover agent allegedly advised the group on how to blow up a bridge to aid their getaway — and promised to supply them with explosives.

An FBI informant, who is an Iraq War veteran, eventually rose to become second in command of the group, the report said.

According to BuzzFeed News, lawyers for the men allege that the informants and the undercover agents gained the confidence of the defendants, stirred their anger at Whitmer and encouraged them to conspire in the plot, even going as far as steering the conversation away from other subjects to how to carry out the kidnapping.

The Iraq vet, they said, even taught them military tactics to use in the operation.

As Buzfeed rather sensibly reports [5]:

An examination of the case by BuzzFeed News also reveals that some of those informants, acting under the direction of the FBI, played a far larger role than has previously been reported. Working in secret, they did more than just passively observe and report on the actions of the suspects. Instead, they had a hand in nearly every aspect of the alleged plot, starting with its inception. The extent of their involvement raises questions as to whether there would have even been a conspiracy without them.

Indeed. It also turns out that some of the supposed good guys in this case aren’t so good:

Meanwhile, Gregory Townsend, one of the lead prosecutors handling the cases against eight of the defendants in Michigan state court, was reassigned in May pending an attorney general audit into whether he had withheld evidence about deals cut with informants during a murder and arson trial in Oakland County in 2000. And on Sunday, in a matter apparently unrelated to the alleged kidnapping conspiracy, one of the lead FBI agents in the case, Richard J. Trask, was charged in state court in Kalamazoo with assault with intent to do great bodily harm.

Yeah, this Trask fellow was charged with beating his wife [6].

I believe we have enough now to realize how close to Chesterton’s story we are getting. Imagine being a fly on the wall in the Ohio hotel room where several of these men met over pizza and beer to discuss training, tactics, weapons, code names, and whatever else—all the while knowing that half to three-quarters of the conspirators were either rats or feds.

The major difference, however, is that in the story, the criminal kingpin was a preternatural genius, while in real life the plotters were a bunch of low-IQ sad sacks [7] who liked to talk about militias and guns and got lured into the plot over social media. In fact, one of the plot’s leaders, Adam Fox [8], was a homeless pot-smoking gym rat with an alleged drinking problem. This is a clear example of how our fake government manufactures fake threats from the Right in order to justify its very real hostility towards legacy America. It wouldn’t be the first time that the FBI has lured the weak and unstable [9] into discrediting the Right.

At the end of this enigmatic novel, Syme appears to have woken up, as if from a dream. Or perhaps he had died and gone to a better place. Chesterton leaves it very open-ended. In any case, Syme finds himself with “an unnatural buoyancy in his body” as he walks along a charming country lane. Beside him is his former antagonist Gregory, perhaps the only true anarchist in the story, with whom Syme is having a delightful conversation. Syme is at peace, finally removed from the spy-vs.-spy strife of the underworld. If any differences remain between order and anarchy, they’re being hashed out in a civil manner by the two friends. It seems Syme is discovering how sweet life can be, especially upon noticing Gregory’s beautiful sister, whom he met in the first chapter.

A dreamy ending to a dreamlike story. A reader cannot ask for more. But upon closing the book, we must realize that, in the century since it was published, the forces of anarchy have continued to grow stronger, at least in the West. If Chesterton were alive today, he’d be shocked at how right he actually was. The pernicious philosophers, mendacious scientists, and degenerate artists mentioned above are now running our governments, our universities, our news media, and our entertainment industries. Syme escaped from all this—or Chesterton at least hints that he escaped. And we as readers feel Syme’s elation.

But for us today, things have gotten so bad that there really is no escape. All we have left is to look the evil in its eye and fight that which we fear the most—because we’re running out of time. From now on, every day is Thursday.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here: